EDITORS

Peter Halley Takes Mel Ottenberg Inside 10 Years of Index Magazine

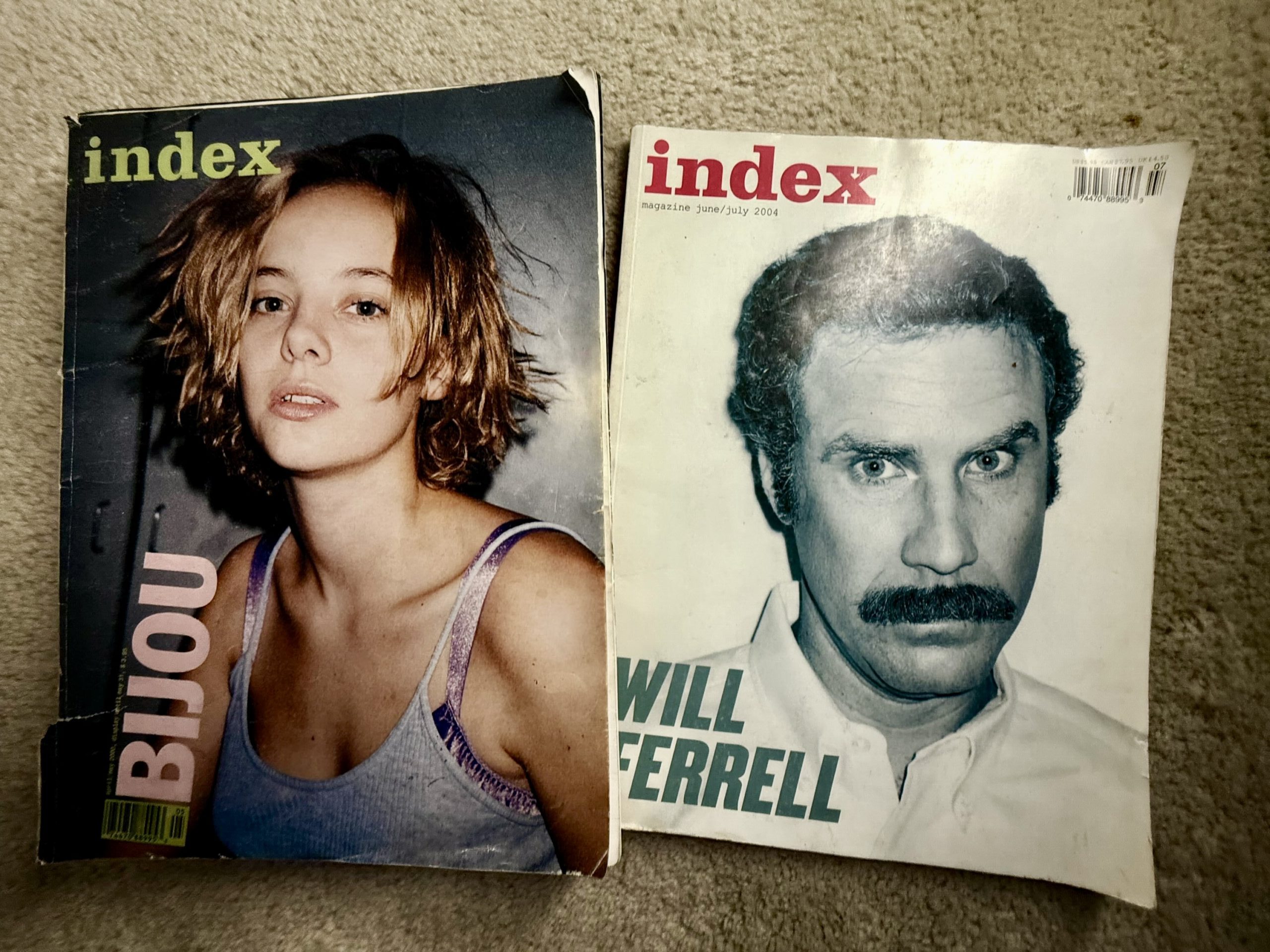

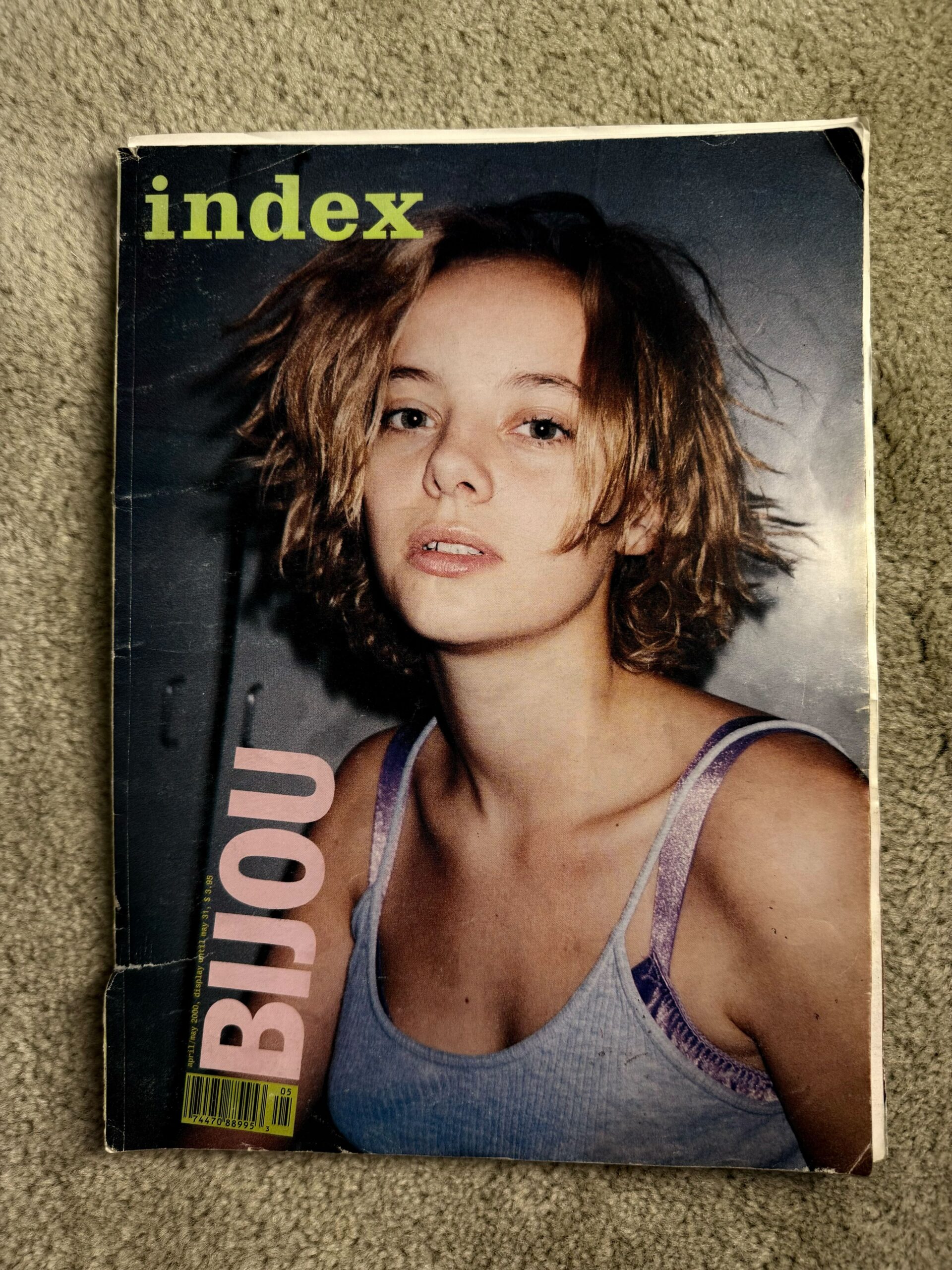

Index was a magazine published in New York between ’96 and ’05. I like Index for the juicy conversations, the raw photography, and the fringe contributors. This week in Paris, there’s a four-day retrospective, on view from September 10th to 14th at Wahter Studio, introducing Index to a new generation of people interested in magazines and culture, which sounds great. I knew the magazine’s co-founder and editor Peter Halley a little bit back then, and since his magazine remains one of my biggest influences as an editor, it was a good time to get on the phone and talk. So last week, surrounded by my personal archives of old Index issues, I called Halley to hear more about the magazine’s legacy and his favorite memories from his decade-long tenure as editor.

———

MEL OTTENBERG: Hey Peter, how are you doing? I’m Mel.

PETER HALLEY: Hi. We’ve met.

OTTENBERG: Oh, come on. You wouldn’t remember me.

HALLEY: I remember you. I remember our photo shoots.

OTTENBERG: Okay, good. It’s nice to see you. How are you doing?

HALLEY: Very well, thanks. And it’s nice to talk to you as well.

OTTENBERG: I was so excited to get this email about your upcoming show because I’m always talking about Index Magazine.

HALLEY: I wasn’t even calling it a show, but it’s been fantastic.

OTTENBERG: It’s in Paris?

HALLEY: It is.

OTTENBERG: So, why did you start Index?

HALLEY: Boredom. It was the mid-90s and the art world was so dead in the water, so I was looking for a project that would expand my horizons. Initially I was hoping to start a school like the Whitney [Independent Study] Program, a small sort of art program for young people in New York, but nobody was interested. And then, Bob Nickas and I were sitting around talking one day and we got the idea to start a magazine instead. I used to write and I love doing interviews, and Bob was such an addicted consumer of all kinds of culture, so that’s how we started it. We patterned it on early Interview, actually. We wanted to run long, somewhat unedited interviews with people we liked, and we wanted to get away from studio photography. And that led us to Wolfgang Tillmans, who was just emerging at the time, so he did our first year of covers, and that had a huge influence on the magazine.

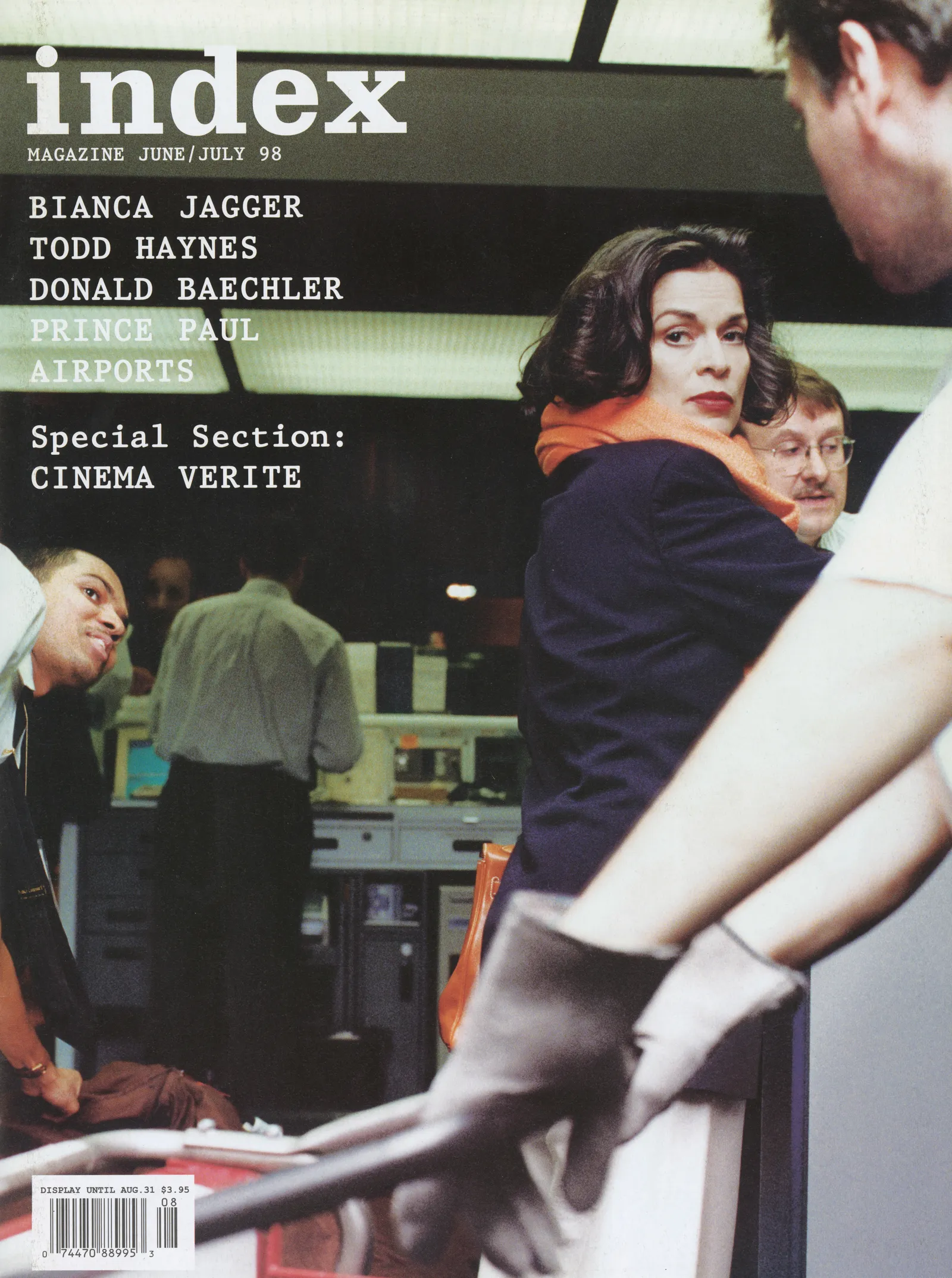

OTTENBERG: Bianca Jagger is one of those, right?

HALLEY: Yes, that was a great cover.

OTTENBERG: That picture was so memorable to me in Wolfgang’s Pompidou show and I just noticed it’s in the Index show.

HALLEY: I’d been in touch with Bianca Jagger and Wolfgang would fly coach over from London to do these shoots. So he was in New York for a few days and Bianca kept canceling the photo shoot, so finally I called her up, and I said, “Bianca, Wolfgang is going back to London tomorrow, so we have to do this.” And she said, “There’s a car waiting for me outside, I’m on my way to Kennedy Airport to fly to India.” Wolfgang jumped on the JFK Express, beat her to the ticket counter, and got the shot.

OTTENBERG: Wow.

HALLEY: It’s a really great story.

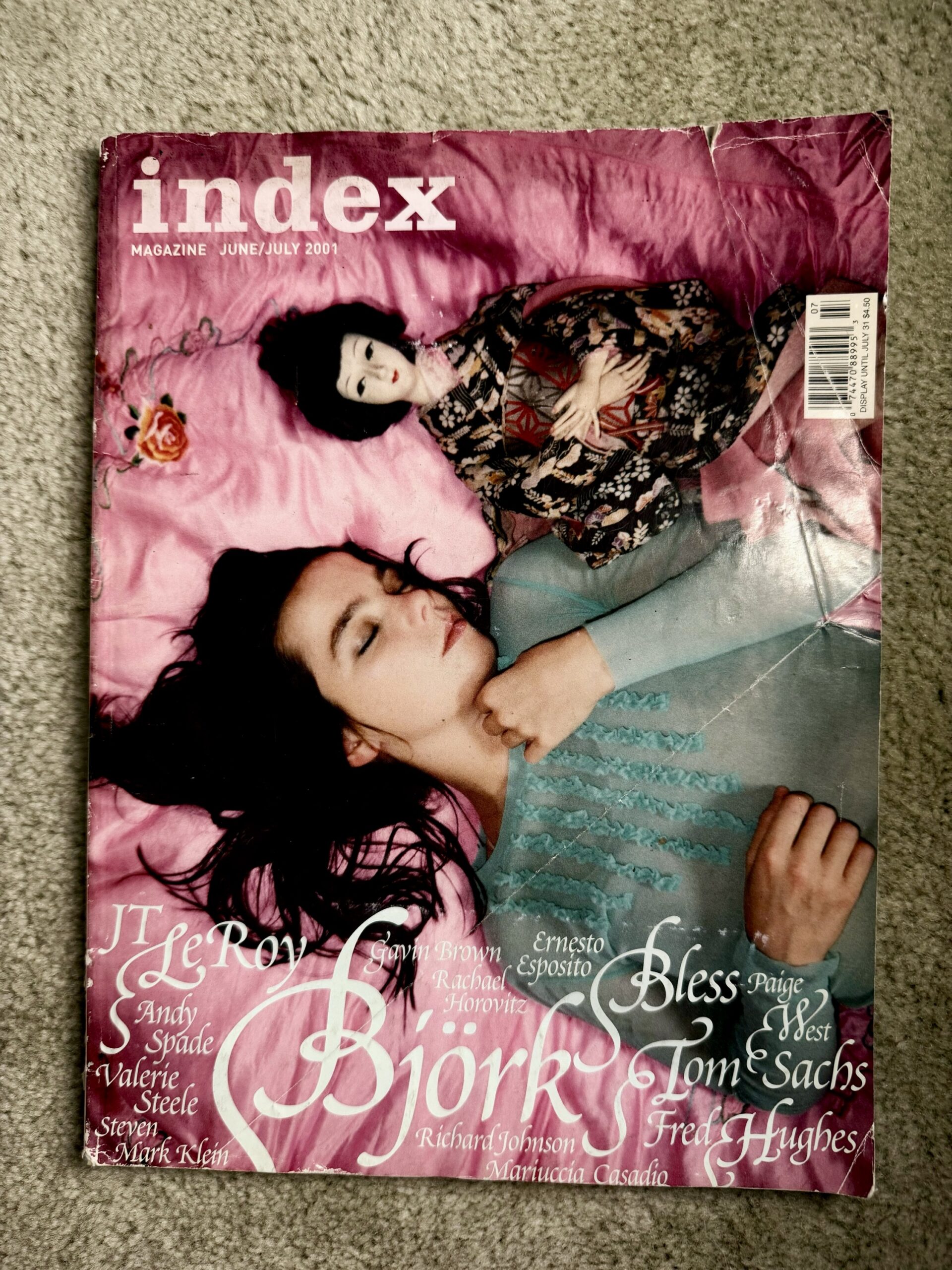

OTTENBERG: There’s so many incredible Index issues. What were the conversations like between you and photographers before. Right here in my pile we’ve got Bjork by Juergen [Teller]. This is a really momentous one. And this is Casey Spooner by Terry Richardson.

HALLEY: Well, with Wolfgang and Terry, and Juergen Teller and Mark Borthwick, you really just wanted to let them do what they were going to do. Terry, just by nature, was a great cover photographer. His style of shooting and the way he used flash just really lent itself to a cover. And that was our commitment, which was based on Interview too—that every cover would be a headshot. Well, they’re not all headshots, but it would be a portrait. The magazine emerged during the heyday of what I would call indie culture, indie film, indie movies, indie bands, and indie fashion, especially in Nolita in New York.

OTTENBERG: And at the time, were there other interesting publications to you?

HALLEY: Well, actually, Vice sort of emerged at the same time, and it really bugged the hell out of me. I thought it was so sexist, and sort of homophobic, and just objectionable in every way. I just couldn’t believe this magazine existed. I didn’t like the content, but they had a great business plan, which was to give the magazine away—but not everywhere, only at select outlets. So, they had a huge circulation and that brought in the advertising and the rest is history.

OTTENBERG: Interesting. What specific moment of Interview moved you and inspired Index?

HALLEY: The 70s. When I lived in New Orleans in the 70s, Interview Magazine was sort of like my lifeline to New York at the time. And I remember going down to the newsstand downtown and picking up issues of Interview. Looking back at, it’s really interesting because 70s Interview was not great—it was kind of boring, kind of uneven, and the design was pretty darn shoddy. But the media world was so much less competitive. Interview and Warhol, they weren’t competing with anybody, they just had a niche all to themselves. And we really identified with the idea of Interview Magazine doing high and low—somebody in high culture, somebody in popular culture. I just happened to be reading a book about Condé Nast, Empire of the Elite, and I hadn’t thought of it consciously so much, but Tina Brown’s version of Vanity Fair also really picked that up in the early 80s. Reading this book about Condé Nast, I began to think of Index as sort of the anti-Vanity Fair, because it didn’t deal with wealth and celebrity and status, but it tried to achieve the same mix in every issue.

OTTENBERG: There’s a real mix of Hollywood, cinema, and fringe people, from what I remember. How did you guys figure out who would be on the Index covers, who the quintessential cover stars were?

HALLEY: Well, it was who we wanted to get and who we could get. The holy grail that we never got was Bill Murray. Everybody who worked at the magazine always wanted to get Bill Murray.

OTTENBERG: Oh, yeah.

HALLEY: That was unattainable, the unattainable holy grail. But great things would happen. Some of them were people I met, some of them were people the photographers knew. For example, Juergen Teller knew Björk. We got Helmut Newton through an art dealer friend of mine when he was having a show in Switzerland. I forget how we got Daniel Day-Lewis, I think he just liked the magazine. We put Scarlett Johansson on her first cover and we got her because we really wanted to interview the director of the film, but he wouldn’t do it. But Scarlett Johansson, who was like 16, was available. So our photographer, Leeta Harding, flew out to Arizona where she was shooting and got these great pictures of her.

OTTENBERG: What a great picture. I’m staring at her right now.

HALLEY: Yeah.

OTTENBERG: Slava is another cover I can’t find right now, but I absolutely kept, and it’s in this apartment somewhere. Was that Ryan’s idea?

HALLEY: It might’ve been Ryan McGinley’s idea. The first time he shot somebody he didn’t know, it was for us. We actually put him on a plane to Tokyo, he was like 18 years old, to shoot Momus. Those kind of adventures were exciting. Our contributing editors were really a huge part of it. They were diverse, and I would bring in people I met through the art world. But we always tried not to do too much with art. One cover we did in 1996, which is sort of relevant now, is Mira Nair, who’s the mom of [Zohran] Mamdani, who’s running for mayor.

OTTENBERG: Fantastic.

HALLEY: Wolfgang shot that cover.

OTTENBERG: So you, as a painter, were sort of like, “Let’s get into all the parts of culture—film, documentary, fiction—that are not part of my art world thing,” right? Not so much fine art, but everything else that interests you in the world.

HALLEY: We wanted to make a magazine that covered the range of culture. And as an artist, there was a kind of assumption that artists were influenced by art history and looking at other art. But I knew a bunch of artists, and I knew that artists listened to music and watched movies, and I liked the Talking Heads. So the idea of bringing all these cultural forms together was really important to me.

OTTENBERG: I really like the way that the interviews are edited. The style feels unedited, but I know it’s edited. Who was doing all that? It’s a very, very clear voice.

HALLEY: Well, we had three editors. First Bob Nickas, then Cory Reynolds, and then Ariana Speyer, and I guess they were each editor for two or three years, making up 10 years in all. We would go in with a very fine scalpel and try to clean things up. But it was a hell of a lot of work.

OTTENBERG: But you always kept it juicy.

HALLEY: Yeah, we didn’t change the content. We just tried to clean up the sentences so people could read them.

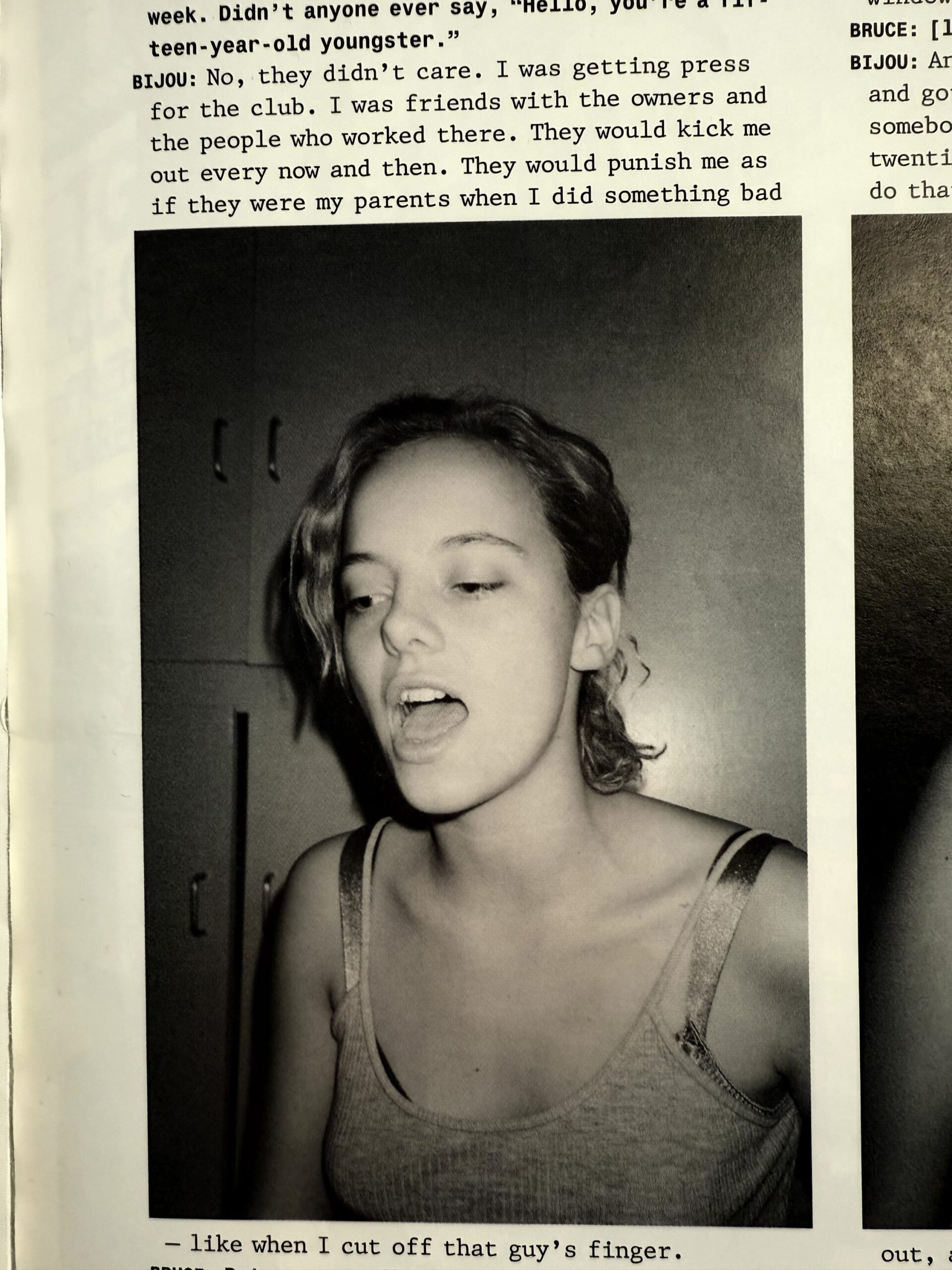

OTTENBERG: The Bijou [Phillips] and Bruce LaBruce one is my favorite because she’s a bad girl, and she’s infamous, and Bruce is saying that they’re on a harmless club drug while doing the interview and she’s talking about chopping that guy’s finger off at Spy Bar. It’s very nonchalant, and it’s truly heaven.

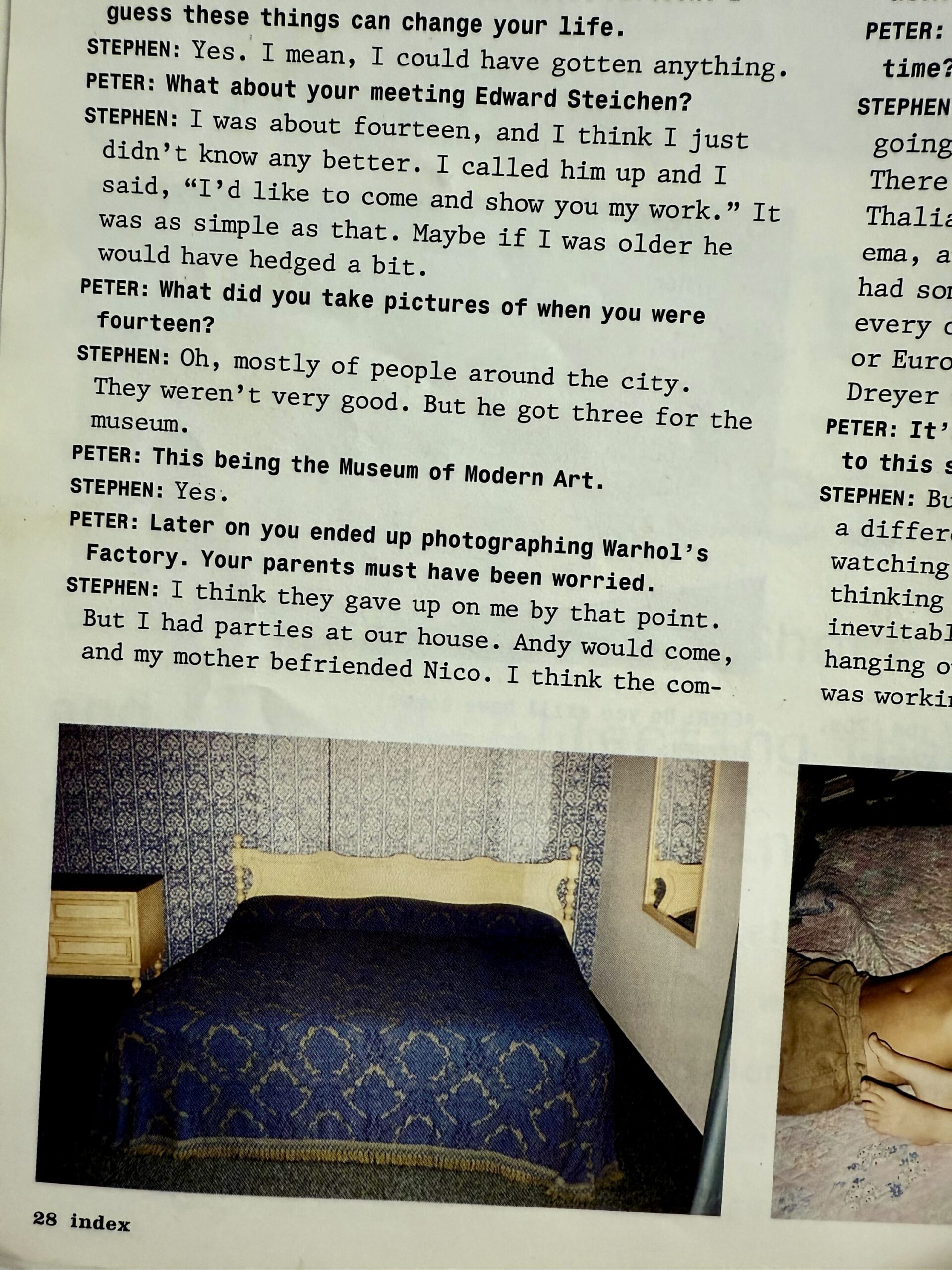

HALLEY: Yeah, I didn’t pay any attention. In that issue, I was doing Stephen Shore. I’d admired him since I was 20 years old, and I’m very proud of that interview because I think it really helped revitalize the reception to his work.

OTTENBERG: Oh my god, I really remember this issue. I probably learned about Shore through this, because I remember the layouts, I remember the Agnès b interview here. Oh, on the set of Gus Van Sant’s Easter. There’s also this one, I just found it, and I was reading it earlier today, it’s the first time I learned about Paradise Lost and the West Memphis Three. There’s an interview with the documentarian that did that. Oh, yeah, right here, it’s the same issue. Joe Berlinger. “Is the devil alive and well in Arkansas, or have three innocent teenagers been framed?” Where did these stories come from?

HALLEY: I don’t know, I was just the publisher. I was more like the referee, and I would always do the final mix of what was going to be in the issue. Because it was always five interviews and a middle section. So it was up to me to choose, among the ideas on the table, how to mix them together. I was basically sitting around the table and basing it on what different people were pitching. And I’m sure you agree, that’s such an exciting experience to try to figure out what’s going to create a great issue.

OTTENBERG: Oh, yeah. It’s really so fun to sit around with an intergenerational table of people who are all interested in different things and get the right mix of high and low, old and new.

HALLEY: That’s a good point, because I was in my early 50s and they were all in their 20s, maybe 30s. It was me and the kids.

OTTENBERG: Were the kids and the art directors and the editors fighting over covers, or was it all fairly chill?

HALLEY: Well, I really had final say on the cover, but then half the time we didn’t get the cover we wanted. So making sure we had a great cover was stressful, because some of the people we wanted to get were just not going to be available. It was pretty rare that we just didn’t have an image we could use on the cover. Some are stronger than others, but I think generally they’re all pretty great.

OTTENBERG: I agree. Do you remember anything in particular that really got you guys in trouble?

HALLEY: You know, we never got in trouble. The weirdest thing that happened to us was this whole episode with… who was the writer who was a fraud?

OTTENBERG: JT LeRoy?

HALLEY: JT LeRoy.

OTTENBERG: Before this call, I just read a short thing that JT LeRoy wrote about Asia Argento in one of these. Shit, I want to read it in this interview to quote it. But go on, tell me more, I’m going to try to find it.

HALLEY: It was really complicated. Somehow, JT LeRoy got in touch with us. We sent Roe Ethridge to San Francisco to photograph… let’s just say, “that person.”

OTTENBERG: Laura Albert is the name of the fake JT LeRoy. Savannah Knoop is the name… the real name of the person that Roe would’ve been photographing, the person pretending to be JT LeRoy.

HALLEY: Being the sister of the writer?

OTTENBERG: Yes, exactly. Being the sister-in-law of the writer, yeah.

HALLEY: Yes, that’s who it turned out to be. But they controlled the shoot a lot, and JT LeRoy, or Laura, said, “Oh, I don’t want my face in the pictures.” So Roe just photographed the hands and I guess some other images without the face. And then we ended up sponsoring this benefit for the psychiatric hospital in San Francisco that had helped JT LeRoy recover and establish him or herself as a writer. And it was this huge benefit at the Public Theater, with all these high-profile Hollywood people singing JT LeRoy’s praises.

OTTENBERG: Peter, I was there. And I want to talk more about this because it’s fucking… This is like a fever dream, you know? No one knows, it’s before video on phones and shit.

HALLEY: It was crazy.

OTTENBERG: No one knows what I’m talking about when I tell people about this story! [Laughs] Remember that? It’s at the Public Theater, and what year do you think it is? I think it’s 2004.

HALLEY: It might’ve been a little earlier.

OTTENBERG: Okay.

HALLEY: The magazine closed in 2005.

OTTENBERG: So I was the costume designer of Asia Argento’s The Heart Is Deceitful Above All Things which is this movie of the second JT Leroy book of the same name. And we filmed that in October 2003, which is around the same time we met, and I styled stuff for you guys.

HALLEY: And do you remember Winona Ryder introduced her?

OTTENBERG: Yes, I do. Winona Ryder and Tatum O’Neal and Debbie Harry were all going up competing like, “JT LeRoy is my best friend. I am best friends with JT Leroy. JT Leroy means everything to me.” And then, wait, I have to say this for posterity because I don’t ever talk to anyone about this, but JT LeRoy gets on stage. And they’d been saying, “Oh, JT has stage fright.” And I wonder if you remember this the same way I remember it. Do you remember who else talked before JT gets on stage?

HALLEY: There was a man who was directing a movie. There was also someone who played the guitar.

OTTENBERG: Oh my god.

HALLEY: And the weirdest thing, in my recollection, is Winona Ryder got up there and said, “The way I met JT is I had two tickets for the opera in San Francisco and my friend couldn’t come, so I had an extra ticket and there was this little waif standing outside, so I invited him in.” And when I found out what the real story was and the fact that she made up this whole thing on stage…

OTTENBERG: Amazing. Incredible. And then they were like, “Oh, JT is very shy. We must protect JT.” And then JT comes on stage. And JT’s outfits were amazing. She’s in this top hat with long hair and a weird ragamuffin suit. And JT did this performance of a person with stage fright, sort of like Danny in The Shining when he is drooling because he saw the old lady. Do you remember? And I was like, “Oh my god, JT is such a fraud and this is pure camp.: I’m just loving this moment. It’s one of the great pop moments of my entire life, Peter.

HALLEY: I agree.

OTTENBERG: It was un-fucking-believable.

HALLEY: And backstage afterwards was even better.

OTTENBERG: Can you tell us anything about that that you remember?

HALLEY: It was more of the same, all these gals sitting around on sofas and acting starstruck.

OTTENBERG: Incredible. When I was doing costumes for The Heart Is Deceitful Above All Things, the Asia Argento movie, JT was always like, “I want to go with Mel to the thrift store,” because I was always going to the thrift store to figure out the costumes. But [Laura Albert] was like, “No, you can’t go with Mel, I must keep you here.” One day, she let JT come with me and it was a really dramatic moment. Marilyn Manson was on set that day and everyone was freaking out. And we went and we smoked cigarettes under a tree in this beautiful light in Knoxville, Tennessee. And the way I saw it was, “JT is a woman, this is not a man.” All of the natural hair on this person’s face is a woman’s. And then when I went to this event, I realized it was all fake. But it was genius.

HALLEY: Now, here’s the funny thing. Hardly any writers hand in almost picture-perfect prose, totally grammatical, no errors, no editing. Another one was Wayne Koestenbaum, totally perfect pitch. But JT LeRoy’s stories were really, really good—not in terms of content, but just in terms of perfectly styled, grammatically correct, no errors in the writing. So that was a real puzzle.

OTTENBERG: Yeah, it is a puzzle, but also I think that someday people will rediscover Laura Albert’s Sarah and The Heart is Deceitful [Above All Things] and find it interesting.

HALLEY: Later on, I tried to get Laura Albert to write stuff for us when Index became a website, and the prose wasn’t as good. So I’m actually not totally convinced it is her. There’s maybe a third person, but that’s just my conspiracy theory.

OTTENBERG: Well, it makes me so happy to talk to someone who was there. I’m bummed that I’m not going to be in Paris, but I’m glad that people will see it. And thank you for the impact you’ve had on my career, it’s really big.

HALLEY: I really appreciate it. I guess the right word is “gratifying.” I’m gratified that people of your generation remember the magazine and that it created some kind of interesting model for how one might go about doing cultural things. One thing I should say is, we started off trying to figure out how the magazine would be sustainable. Doing interviews is not so expensive, doing snapshot photography is not so expensive, so that was the business plan, which was very much based on Andy Warhol, who, in many ways, was very cheap.

OTTENBERG: Yeah. Cheap and high impact.

HALLEY: That’s the secret.