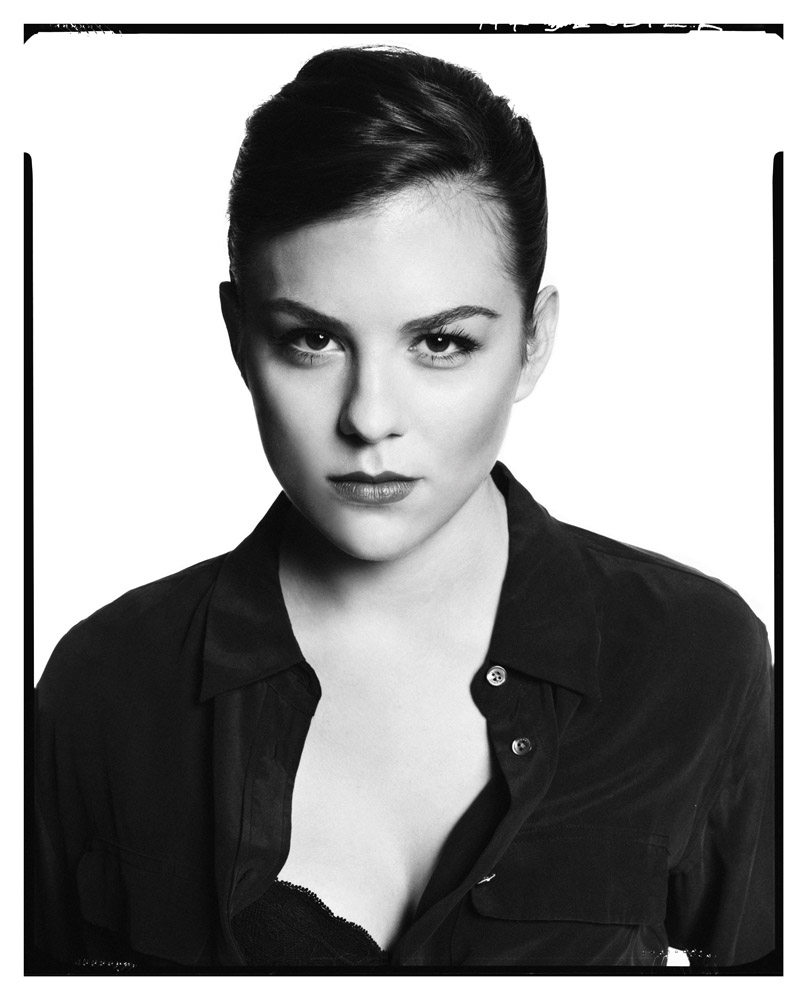

Morgane Polanski

“Before wanting to be an actor, I wanted to be a director. As a child, I would invite friends to my house. I was very authoritaire. If my parents started to talk during the performance, I’d grab them and say, ‘Don’t speak. Don’t laugh. Watch!’ And if my friends didn’t do what I told them, I started hitting them. My mom was like, ‘Morgane, if people don’t do what you want, you can’t hit them.’ And I said, ‘But she was supposed to move there!’ When I grew up, I realized how much responsibility directing was and I thought, ‘Whoa. For the moment, I’m just going to let someone else tell me what to do.’ ”

Coming from any other 22-year-old, this childhood recollection of directing 5- and 6-year-olds in a stage performance might seem like a precocious anecdote that calls to mind the Tenenbaums. But the parents whom Morgane Polanski were shushing were her iconic director father, Roman, and her equally iconic actress mother, Emmanuelle Seigner.

This month, Polanski makes her television debut as the princess of France in Season 3 of the History channel drama Vikings. The character of Princess Gisla, great-granddaughter of Charlemagne and guiding hand of her father’s kingdom, is one part elegance and two parts grit. Gisla’s silken raiment and gold brocades sharply contrast the brutal world of Viking raiders. Polanski arrived on set in Ireland last summer like a leopard slinking into a bar fight. “The makeup team was like, ‘Finally we get to make someone pretty!’ ” she says. When asked if she was the kind of girl who dreamt of being a princess while growing up in Paris, Polanski laughs. “Not at all! I was obsessed with vampires. I loved Snow White. I like the dark side.” That fits the tone of Vikings. The show’s creator and writer, Michael Hirst, strives for realism in his depiction of life during the Dark Ages. Polanski beams when she talks about Princess Gisla’s power: “Michael writes great parts for women. He doesn’t just write these roles where the women are pretty flowerpots. His women are brave and bold. They don’t just … sit.”

The directors whom Polanski most admires—David Lynch, Paul Thomas Anderson, and David Cronenberg—can be seen as the heirs of her father, filmmakers wrestling with the problems of consciousness in immediate physical terms, with bodies showing interior trauma rather than abstract ennui. “I like psychological thrillers,” she says. “I like to be challenged. I like to be shaken. When I leave a movie, I think, ‘This is what I want to do to people. This is how I want to make people feel. This is what movies should do.’ ”

Vikings is, in many ways, the perfect marriage of the psychological confrontation that Polanski is after—from the perspective of the French, the Vikings invade as a horde of embodied screams—and this world is a place where a princess not only assures her doddering father, but bristles with ferocity. “I love women who have some primal beast in them,” she says. “I like women who tell stories and who aren’t scared of not being pretty.” Those words could also be an apt description of what makes her mother’s performances so haunting and powerful.

More than anything else, Polanski seems thrilled to learn the subtleties of the craft. She graduated from drama school in London last spring and is currently working on an original script with a friend and plans to try her hand at directing when the time comes to film. I get the sense that it might not be long before she is blocking actors again and calling for quiet on the set. But she puts a quick end to speculation that there might soon be another Polanski behind the lens: “It’s going to be acting for a long time.”