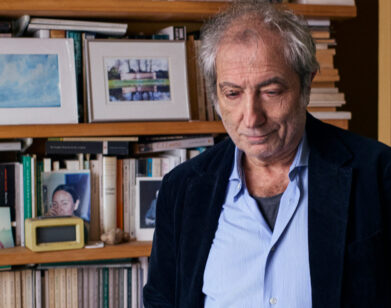

Imran Amed

IMRAN AMED IN LONDON, JULY 2015. WAISTCOAT AND PANTS: THOM SWEENEY. SHIRT: CORNELIANI. STYLING: ISABELLE KOUNTOURE.GROOMING PRODUCTS: JOICO, INCLUDING MATTE GRIP TEXTURE CREME AND HUMIDITY BLOCKER. GROOMING: GIANNI SCUMACI FOR JOICO HAIR CARE.

It became clear to me that I could be a bridge between the creative world and the business world. IMRAN AMED

How are we to define fashion journalism today? Industry stalwarts like Style.com have blended editorial with e-commerce; the digital sphere is ever more crowd-sourced, anarchic, and sprawling; a single Tweet can preempt a New York Times push notification. Even for the most voracious of content consumers, Kim Kardashian’s Instagram feed is as necessary as a subscription to WWD in understanding fashion’s ever-refreshing landscape. Much like the industry itself, fashion news coverage is growing and unarguably more democratic, global, and crazier than ever. Sifting through quantity for quality has become a part of the game. Yet, out of all the outlets angling to be the next big thing, in-the-know readers have already anointed the digital broadsheet of the moment, which delivers the must-read trade news of the day to your e-mail inbox promptly at 6 a.m. London time, for free, straight from the Business of Fashion.

In 2007, BoF began as a “one-man band,” with then-31-year-old Imran Amed, a Canadian-born fashion blogger, writing from his Notting Hill living room. In the years since, the site inched its way from Amed’s semi-weekly dispatches toward a multifaceted destination at the top of insiders’ required reading lists—reporting on the luxury market in Macau and emerging economies in Latin America side by side with interviews with Karl Lagerfeld and Raf Simons. Throughout that time, and consistent with Amed’s background, BoF has always been strong on numbers. Amed’s business bona fides—degrees from McGill and Harvard Business School; a consultancy gig at McKinsey & Company, a firm with a series of Fortune 500 companies on its client list; as well as a slew of consultant positions with the likes of LVMH—helped put him and BoF on a course for major expansion. In the past few years, Amed has spearheaded the launch of a BoF special print edition, a careers marketplace, and the “BoF 500,” a yearly updated digital index of not just the major designers, photographers, and stylists of the industry, but also the CEOs, investors, and executives that make it run.

One of Amed’s devoted subscribers and fans happens to be a savvy entrepreneur in her own right, designer and fashion icon Diane von Furstenberg (who will, coincidentally, co-host a party to celebrate the BoF 500 2015 during New York Fashion Week along with Amed). Calling from her office in the Meatpacking District on a morning in mid-July, von Furstenberg connected with Amed, who was in London, to hear all about his rise from the couch to the front row.

DIANE VON FURSTENBERG: I am very excited to interview you, because I am a huge fan of yours. I think that you have had, in a very short time, a huge impact on the industry. You were born in Canada, and your parents moved there from Nairobi, correct?

IMRAN AMED: Exactly. My parents landed in Calgary in December 1974, straight from Nairobi. They were immigrants, like many people coming to build a better life. My mom was five months pregnant with me when they landed.

VON FURSTENBERG: Do you have siblings?

AMED: I have a sister who’s 14 months younger than me. She ended up taking a much more academic path. She’s a pediatric endocrinologist. She focuses on diabetes and obesity in very young children.

VON FURSTENBERG: Clearly, your parents pushed you in school.

AMED: Education was for them, and for us, one of the most important things growing up. But luckily my parents also focused on helping me develop my creativity. I always wanted to do creative things, but I was really interested in entrepreneurship. My family comes from a very entrepreneurial culture, so business was always something I was interested in.

VON FURSTENBERG: Are they Indian originally?

AMED: Yes. My ancestry is Indian, and there’s a big Indian community that’s been in East Africa for over 120 years. So we come frovm that kind of enterprising community. That was always a part of me. When it came time to make a decision about what to do at university, I ended up going into business. But to be very honest, it took many years for me to figure out what I wanted. I think I always knew I wanted to have an international career, coming from such a diverse background. I was always interested in the world. I was always interested in building things. Even back in elementary school, I was a leader, but a leader who didn’t know how to channel my leadership skills in a constructive way. When I was younger, it probably came out as being more of a bossy little kid.

VON FURSTENBERG: [laughs] I think you still are.

AMED: [laughs] Of course, part of me still is, but I’ve had to learn to channel that in a way that works for other people.

VON FURSTENBERG: So you got an MBA from Harvard Business School. Then you went to [the consulting firm] McKinsey & Company. How long did you stay at McKinsey?

AMED: I was at McKinsey for just under four years, which was a pretty intense period. McKinsey is one of these incredible places where you’re surrounded by the smartest people you’ll ever meet. I worked with clients in Australia, in South Africa, all over Europe, all over North America. I learned about building a company and organization where people can find value and create value in their work. Professionalism is, for me, such an important part of making anything a success, because if you’re a professional and if you approach things professionally, then that dedication and that discipline is part of what makes things successful.

VON FURSTENBERG: I think that’s very much a thing of your generation.

AMED: It was a longer period to make the decision to leave. “The Firm,” as they all call it, with a capital F, they started talking to me about partnership. In order to be a partner, you have to choose a specific industry or sector that you want to operate in. Although my work was really stimulating, the sectors I was working in weren’t industries I really had a passion for. I worked in financial services, I worked in the pharmaceutical industry, I worked in real estate and construction. I really enjoyed being a generalist, hopping in and out of different sectors and learning different things and going to different countries. All of a sudden the choice of having to focus on a specific sector made me realize that there probably wasn’t a long-term career for me at McKinsey, so I asked to take a leave of absence. I was pretty burnt out by this stage. I had been working 80- to 100-hour weeks for many years.

VON FURSTENBERG: How old were you?

AMED: I was 28 or 29. Maybe I was just about to turn 30, and I was having an early mid-life crisis. I had gone to all these prestigious schools and worked at all these prestigious companies, but I still wasn’t feeling the same passion or excitement about things as I did when I was younger.

VON FURSTENBERG: So what did you do?

AMED: I went through a very intense meditation course in South Africa, just outside Cape Town. The meditation technique is called Vipassana. Basically you spend ten days in complete silence.

VON FURSTENBERG: Silence, nothing is better.

AMED: You don’t talk, you don’t read, you don’t interact with anybody, you don’t listen to music. You basically remove all stimuli. It was that period while I was at this mediation retreat where I started thinking about all of the things in my life and what made me really happy. I thought back to the times when I used to go to the record store and pick up Billboard magazine and analyze the music parts and figure out who went up and who went down.

VON FURSTENBERG: Here goes your BoF 500 list!

AMED: I started thinking about things like, “Well, what I should do is figure out a way of taking my analytical and business skills and applying them in a creative industry.” After all the thinking was done, I really did learn how to meditate. That has become a tool for me that I use to keep me clear, calm, and sane in what is a really busy world we live in. I came back to London. I told McKinsey that I thought it was time for me to leave. They were very supportive. I did one last project, and then it was September 2006 and I left. I started having conversations with people in music, television and film, and fashion. The fashion industry really began to capture my interest because the music industry was in a state of complete disarray. I actually got a job offer with a big TV company, but when I walked in there, I felt like it was just going to be another big corporate job. I met some people at the British Fashion Council, and I started meeting all these young fashion designers: Erdem [Moralioglu], he was in his second season; Roksanda [Ilincic], she was just starting out. The more of these designers that I met, the more I learned that they were very creative but they had no business skills. No one taught them anything about business, but overnight they were expected to run these businesses. It became clear to me that I could be a bridge between the creative world and the business world—the creative side of fashion and the business side of fashion. In hindsight, it was very naive, because I didn’t know anything about how the fashion business worked. I ended up starting this company, which didn’t last very long, but it was an incubator for young fashion designers. Working on that start-up, I really began to learn about how the fashion industry worked and I started meeting all sorts of people from around the fashion industry. That was the year I met [Net-A-Porter founder and executive chairman] Natalie Massenet, Louise Wilson, and the people at Central Saint Martins. The more people I met, the more excited and passionate I became about this industry. I also felt like, for some reason, people didn’t take it seriously as a business. They think it’s this super-glamorous, frivolous, vacuous group of people going to parties and drinking champagne.

VON FURSTENBERG: Listen, an enormous portion of the world’s population is involved directly or indirectly with clothing.

AMED: Exactly. For some reason, the world doesn’t see it that way. It started becoming quite clear in my head that fashion was a big business and needed to be seen as a business. The mainstream media weren’t taking it very seriously. I started keeping a private blog, a journal of my experiences in the fashion industry, and I shared it with some of my family and friends. There was a password on it, and every time I met someone interesting or did something interesting, I would just write about it. But when my start-up didn’t work out, I found myself with a lot of extra time. So I decided to take off the password, skin a new blog, and start from scratch. That’s how the Business of Fashion was born. It was born from a blog.

VON FURSTENBERG: And that was when?

AMED: That was in January 2007. I was really lucky. I managed to get some consulting work, and the first client I had was LVMH. Then I had some young designers and some technology start-ups. I was earning my living as a consultant, and BoF was my little evening project. But the more time I spent in fashion, the more it became clear—

VON FURSTENBERG: That you had an eye.

AMED: It was my little passion project. At first I used to write once or twice a week. It would just be something that interested me. People told me back then, “If you’re going to write a blog, you should only write 300 words per blog post.” By the time I got to 300 words, I felt like I was just getting started. So I would just write as long as I wanted. I sent it to some of my family and friends, but other people started discovering it. Then people were giving me feedback. I was just trying things. I didn’t really know much about how the technology worked, but what I could tell was that by writing BoF, it started bringing me into contact with other people who were interested in this intersection of the creative side and the business side of fashion. I felt very connected to my work for the first time in a very long time. I was very stimulated during the day with my client work, but in the evenings, I had this outlet to create things. I used to take all the pictures, upload them, crop them, and do all the writing. It was like a one-man band.

VON FURSTENBERG: How big of a readership did you get as a one-man show?

AMED: In the first month, I think we had 113 readers. Then the first year, there were 41,210 readers. But you have to understand, to me, sitting on my sofa, that was insane. And they were from all over the world, Diane. They would write me letters. Then people started asking me for “expert opinions,” and I was this little sofa pundit. For whatever reason, people felt that I had something to offer. The next challenge was: How do I go from creating one or two pieces of content per week to creating something that people would come to look at every day? There were only so many articles that I could write on my own. By this point I had become a voracious consumer of content about the fashion industry. I knew that there was a lot of interesting content being created, but it was all over the internet. So the next stage was to create the “Daily Digest,” which is a curated list of articles that I was recommending that other people read. I had my first contributor work with me on creating this list every day. All of a sudden, BoF went from this sporadic, once-in-a-while article to a daily place where you could get some insight about the fashion industry. That e-mail would go out every morning, at six in the morning London time, and that became the real trick. When people started seeing that e-mail every day in their inbox, it began a daily relationship with BoF. Then from there, various people started writing for BoF. I met some people through the comments they were leaving on the website; I met some people on my travels to different countries. By this time I was traveling all over the world because people were inviting me to come speak at conferences or to meet with their companies or to meet their students. It was amazing because this is where I got the idea that BoF was really a community. At the same time, I was still trying to make a living as a consultant, and at a certain point it was just not sustainable.

VON FURSTENBERG: So then what did you do?

AMED: I had some people approach me about investing in BoF. There were media companies and there were angel investors and former media executives looking for a new thing. For me, it was still my little project, but it became clear that there was potentially some commercial opportunity. The feedback I was getting was that people saw real potential. It was still a really small audience, a budding brand, but there was something really special about it that people wanted to be a part of, even from a financial point of view. So I wrote a business plan. The most obvious thing was the media side: you could take advertising and sponsorship. There are all these new media companies, like Vice and Refinery29, that work with all of these brands to make content—we could do that. One of the other things that I saw was that people were always asking me about talent. “Hi, Imran. This is so-and-so from such-and-such company, I was wondering if you know anyone who speaks Mandarin and can help with our new digital strategy for China?” Or, “I’m looking for a really expert merchandiser.”

VON FURSTENBERG: And later you began to use classifieds as another way to monetize it.

AMED: I didn’t think of it as really classifieds, but as a marketplace. We thought that was a really interesting opportunity. There was the idea of doing events, creating conferences and forums. I raised some money and I found a group of investors—

VON FURSTENBERG: Can we know how much you raised?

AMED: We raised two and a half million dollars, off of what was, essentially, a blog. But what I wanted to do was take a little bit of money, a very little bit of money, from a lot of different people.

VON FURSTENBERG: Right. So that they didn’t own you.

AMED: Nobody can, therefore, control or influence what we do, and everyone can help us. We looked for money from the media world, we looked for money from the fashion and luxury world, and we looked for money in the technology world. We have money from investors in China, investors in the Americas, investors in Europe. I always wanted to retain the independence of BoF. This was very important because retaining our independent point of view is, as you pointed out, one of the defining factors of BoF and why people trust it.

VON FURSTENBERG: So where are you now? You have created this very valuable list, you have created a digest, you have created a destination. You have a very clear point of view that is extremely refreshing, always original, and even in the same news that other people report, your angle and your editorship is very original. First of all, how many people read you today?

AMED: We have 150,000 daily e-mail subscribers who are our most voracious consumers, our most loyal audience. We have over half a million unique visitors to the website every month, and we have two and a half million followers on various social platforms. Some of them are very senior executives who read the BoF e-mail before they get out of bed in the morning, some of them are students who obsessively follow us on social media. Then some of them are consumers, people we call the “prosumers” because they read BoF as a source of interest. Even if they’re a lawyer or a doctor, they’re just interested in how the fashion industry works.

VON FURSTENBERG: What’s your next goal?

AMED: Later this summer, we’re going to launch a new project on education. We’re working on a global ranking of fashion schools. We have a Chinese-language website that is becoming more and more of a priority for us. And there are now 25 of us working here at the office in London, and we made our first hire in New York and our first hire in China. So from that sofa project, there’s now a whole team of us, and it’s really exciting.

VON FURSTENBERG: From the sofa to the living room and to the world.

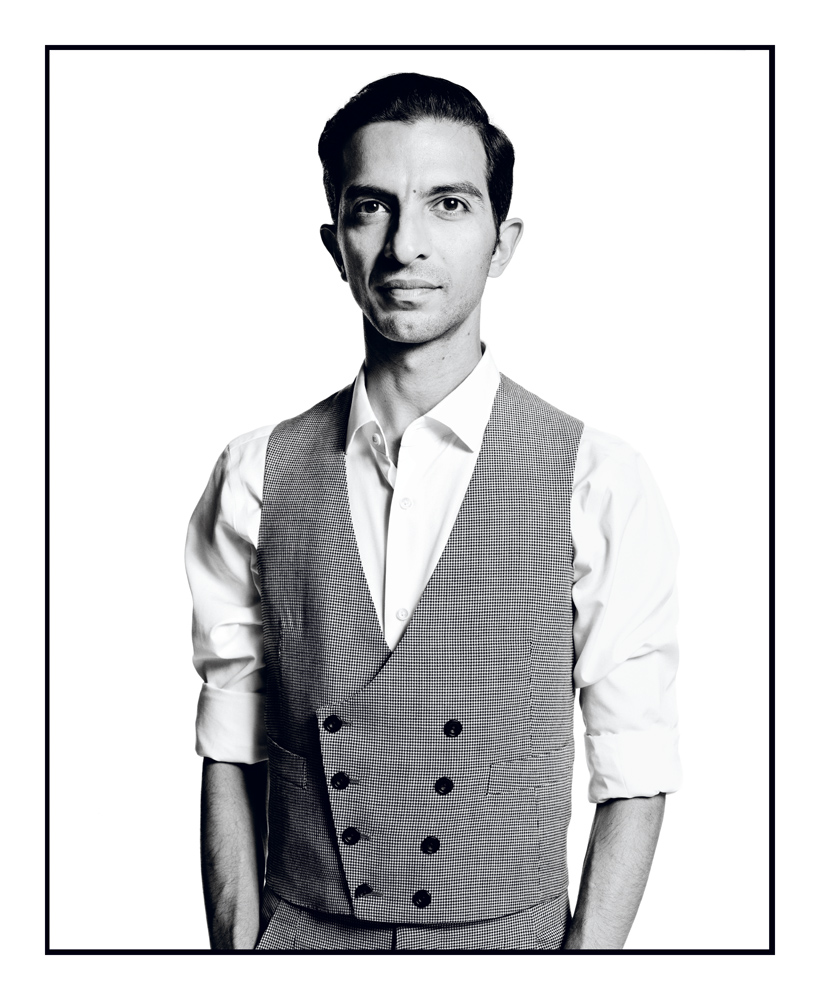

NEW YORK-BASED FASHION DESIGNER DIANE VON FURSTENBERG WILL PREMIERE THE SECOND SEASON OF HOUSE OF DVF ON E! THIS FALL, AND WILL LAUNCH A NEW BAG CALLED THE DVF SECRET AGENT.