BACKSTAGE

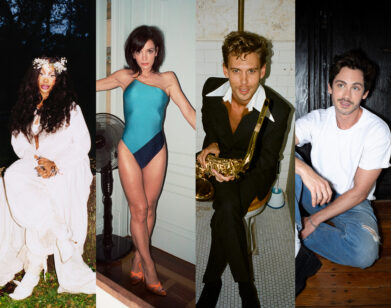

Bess Wohl Wrote a Play About Feminism. It’s So Good That Lily Allen Saw It Twice.

When Liberation first opened Off-Broadway last year, it felt less like a period piece than a transmission from the present day. Now at Broadway’s James Earl Jones Theatre with its original cast intact, Bess Wohl’s most personal play to date has only grown louder, rowdier, and more urgent. Inspired by Wohl’s childhood, during which she regularly accompanied her mother to the Ms. magazine offices in the 1970s, Liberation gathers a consciousness-raising group mid-awakening, tracing the messy inheritance of feminism across generations while asking what, exactly, has been gained—and lost—in the process. “I grew up with this idea that women could just do anything, and that nothing could stop you,” Wohl said. Adulthood, she’d eventually find out, “was a lot more complicated.” It’s fitting, then, that Wohl’s interlocutor was Lily Allen, an artist who knows a thing or two about womanhood, visibility, and surviving in the harsh glare of the public eye. Calling from a writing retreat in Mexico, Allen and Wohl veered from shame and nicotine withdrawal to motherhood and community. Below is their conversation, less an interview than a reckoning with art, womanhood, and the tenacity of using of one’s voice.—OLAMIDE OYENUSI

———

LILY ALLEN: Hi, Bess. How are you?

BESS WOHL: Hi. I’m good. It’s so good to see you. How are you doing?

ALLEN: I’m okay. Actually, am I okay? I’m in Mexico doing a writing trip, but they confiscated all my vapes at customs, so I’m jonesing, which is…

WOHL: Oh my god. You’re not allowed to bring vapes into Mexico?

ALLEN: Apparently they banned them a couple of weeks ago—a nationwide ban of vapes.

WOHL: Oh my god. And you can’t get any new vapes?

ALLEN: There may be some black market sourcing going on as we speak.

WOHL: There may or may not be. That is a nightmare. I feel like they shouldn’t be allowed to do that. So you’re kind of going crazy a little bit?

ALLEN: Yeah. I’m having to smoke full-on fucking cigarettes, which, let me tell you… I start touring in a month and this is not ideal. But let’s talk about your fantastic play Liberation, which I saw twice.

WOHL: Thank you for coming—and then coming back.

ALLEN: When did you come up with the idea and how did its structure change through the various iterations?

WOHL: I came up with the idea because my mom worked at Ms. Magazine when I was a little kid. And I would go to Ms. Magazine with her and wonder about all of the amazing women who were working there. I wanted to see them on stage, and I felt like I had never seen—especially—feminism of the 1970s portrayed in a way that felt authentic to me. Not that there was anything wrong with the portrayals I had seen, but it just didn’t click with what I felt. And it was me trying to understand how—I don’t know if you’ve ever had this sensation—to reconcile the things that I was taught as a kid with the reality of my life as an adult. I think everyone has that in different ways. Whatever sort of ideas you grew up with, do they align with your lived experience once you’re a grownup?

ALLEN: Do you think that they did align, or no?

WOHL: In some ways, yes. In some ways, no. I grew up with this idea that women could just do anything and that nothing could stop you and that you could totally have it all. And I still believe that in certain ways, but it was a lot more complicated than I think I understood it to be as a child.

ALLEN: Yeah. My mom was 17 when she had her first child, and then had me when she was 23 or something, in 1985. My mom also got nominated for her first Oscar by the time she was 30, for Best Picture. And she did not come from money. She was a very working-class person. Her dad was a tax inspector and her mom was a primary school teacher. We lived in social housing for the first four years of my life, and when she needed to go out to work and stuff, all the people that lived in the building would take care of us. But yeah, I don’t think it’s like that anymore. I just don’t think that there is that kind of sense of community.

WOHL: I think it’s true. For me, the experience of being a new mom was a very lonely experience, because everyone’s so isolated and there’s very little support out there. And I just remember lying on the floor of our apartment, on the carpet, just staring at the toys scattered around the apartment and thinking, “I don’t know who to reach out to. I don’t know how to find my people at this moment.” It was a very isolating moment. And I think you’re right—without that community, it just makes it a very hard and lonely journey. I went to a breastfeeding support group down the block, in a gym, and I was like, “I’m never coming back here.” It was just like, everyone just sitting there crying and nursing their babies. So I think being a woman is just a different experience from being a man, and that’s just part of life. I don’t know, I’ve learned what it is.

ALLEN: You are an especially prolific playwright, with Liberation being your 10th published work. Are you comfortable discussing what your writing process is like, or do you want to keep that secret?

WOHL: It always feels a little bit like I work and work to try to get the words out, but then after I’ve done it, I really don’t know how I did it. It’s like I connected to something that came from somewhere else. My favorite moments as a writer are when I really feel like I’m transcribing as much as inventing. Those are the best sort of flow-state feelings. But just to be really granular about it: I get a cup of tea, I sit at my desk, I take a lot of walks, I do all kinds of things to try to get myself into some kind of a flow state so that I don’t really have to think about what I’m doing. Do you feel that way?

ALLEN: I think when it’s good, it’s like that. But then there’s a whole other process that I go through when things are bad, and that is painful.

WOHL: Tell me—what is it like when things are bad?

ALLEN: When you talk about doing all of these things to get yourself into a flow state, I don’t think I’ve found my process of being able to do that. I would say that 80% of the time that I sit down to write music, that doesn’t happen.

WOHL: Totally.

ALLEN: And that can be extremely frustrating. Because there isn’t a formula for it, and I don’t really know where it comes from.

WOHL: The thing I’m describing happens for me twice a year. [Laughs] And then there’s all of the searching and bad stuff that I write and throw away or just never show anyone. And I mean, all of that—yes—is a huge part of it. You’re hacking away to get to the gold that’s in there somewhere. So to me, that’s not wasted time—it’s an essential clearing out. And now those bad ideas don’t have to take up space in my brain anymore. I can make some space for the good stuff.

ALLEN: That’s good.

WOHL: You have a very serious list of questions.

ALLEN: I do have a pretty serious list. You workshopped Liberation for more than a decade.

WOHL: Speaking of the fucking hard parts…

ALLEN: Yes, I don’t think people realize how long it takes to get these things made. Anyway, what’s the experience like now seeing it performed on Broadway, on a Broadway scale?

WOHL: It’s amazing to see it have more life. The more people that come and the broader the conversation that we’re having with the audience becomes, the more exciting it is. That’s why I wrote it—not the entire reason, but a big part of it is to be in conversation with as many people as possible and share it. And on Broadway, it’s just gotten bigger and stronger and more robust and more joyful and deeper. We’ve had time. And as you said, people don’t understand how much time it takes. When we did it off-Broadway, the actors had had their roles for two weeks before they jumped into rehearsal, and then they were performing three weeks later. Now they’ve had a year to sort of marinate and get into the world of the play, and it’s all so much deeper and richer.

ALLEN: And it’s exactly the same cast that was off-Broadway that’s in the show now, right? That’s wild.

WOHL: Yeah. And I feel so grateful for them. They have seized the text and just made it their own and created so much depth and passion. And right now, they’re in deep conversation with what’s happening in the world, because it’s such a raw moment in American politics right now and people come to the theater carrying all of that. So it’s very alive in the room. It’s sort of like we share this giant sort of consciousness-raising group together, between the cast and the audience.

ALLEN: I got thrown out of the theater for having my phone out in the intermission when I was at your play.

WOHL: At my show?

ALLEN: Yeah. I have two phones and I’d completely forgotten that. When I came in they said, “Can I have your phone?” And I gave them my phone. But then I had my English phone in my bag, and it was buzzing because one of my kids was trying to get ahold of me or whatever. So I took it out and then suddenly this guy was like, “Ma’am, come with me,” and rushed me out.

WOHL: Oh my god.

ALLEN: I was like, “Oh my god, this is so embarrassing.”

WOHL: Oh my god. It’s not a perfect system. Were they nice to you, at least? I hope they were nice.

ALLEN: Well, the guy was not nice, but listen, there’s something that happens at the beginning of the second act and there’s a reason that there shouldn’t be phones in there, and that’s absolutely fine. I’m just very sensitive to being reprimanded.

WOHL: I probably would’ve burst into tears.

ALLEN: I kind of nearly did. And I think it was a couple of weeks after my album had come out, so my name was out and about in the ether. So it was just like, “Oh my god, isn’t that that girl that put out that album? She’s on her phone. What a bitch.” This might be my own internal monologue, by the way. But let’s carry on.

WOHL: I’m glad you’re as neurotic about that stuff as I would be.

ALLEN: Tell me more about your mother, who first inspired the show, and your relationship with her—if you’re comfortable with that.

WOHL: My mom is amazing. She was very tolerant of me writing this play, and I wasn’t sure if she would be because it asks a lot of questions about motherhood and about our relationship. I actually hadn’t shown her a draft of the play before she went and saw it at the Roundabout [Theatre Company]. I had told her that it was very personal and she just kept saying to me, “Write the thing you want to write. Do not hold back.” It makes me emotional to think about it because I felt that she was responding, potentially, to moments when she felt like she had held back, and she didn’t want that for me. I did warn her that I was killing off her character in the play. And I was like, “Mom, I’m going to have to kill you for dramaturgical reasons.” She was like, “That’s fine. You’ve done way worse.” And then I think it took her a few viewings of the play to really feel comfortable and be able to receive it as a work of art beyond our relationship. But ultimately she got to the point where she really could, and did, and she’s been so supportive of it. I think it’s brought us a lot closer. And now I feel like I couldn’t have done it without her.

ALLEN: That’s so nice to hear. I’m very happy.

WOHL: And also, not to spoil anything, but there’s a final conversation between a mother character and a daughter character in the play that was very much taken from conversations that I had actually had with my mom. So in that way, she is directly in the play.

ALLEN: And obviously, there were things going on in the world at the time that prompted these meetings that take place in the play. Do you think that there are things that are happening in the world today that explain why it’s particularly resonating at this point in time?

WOHL: I mean, yeah, I do.

ALLEN: What are they?

WOHL: What could they be? What could they be? [Laughs] It’s interesting because we spent a lot of time looking back at the ’60s and the ’70s as we were making this play. But also, the intent was to make the play feel very current and alive and in the moment. And we’re in a moment where the world feels terrifying. We’re seeing things in the news every day that seem to be taking us to a new level of outrage and despair and a sense of not knowing where this country’s going. And what’s interesting in working on the play was looking at how the late ’60s felt that way to a lot of people as well. But also, I think people come in thinking about right now—what are we going to do right now, and how can we come together in community, resist the isolation, resist the despair, find something hopeful, and walk out of the theater feeling energized and a little more alive. You can really hear it night to night. People are responding to the events of the day, and they’re feeling them again as they watch the play.

ALLEN: What are some sort of conversations you hope the play generates among audiences? You and other people who have worked with you have mentioned that you always have something impossible or never done before at the heart of your plays. In Liberation, there’s the nude scene. What about the nudity feels impossible or new?

WOHL: Oh, what a good question. I wouldn’t say I start by thinking, “What’s the hardest thing I could do?” I start with characters or an idea. But in that process, I often come across something that feels really exciting, something that maybe I’ve never seen before. It’s a little bit daunting, I want to try it, and it sort of hovers in the distance as a destination that I’m going to reach at some point in the process, so it keeps me writing. It’s like dangling a little carrot, and I sort of go towards it thinking, “If I follow this path, I will get to this really exciting thing that I want to attempt.” But I don’t necessarily ever want it to feel like a gimmick or a party trick. I always want it to be deeply embedded in the characters and the needs and the situation that I’m exploring.

ALLEN: Yeah. The nude scene doesn’t feel shocking, I don’t think. It’s interesting how quickly you’ve become comfortable with it.

WOHL: I was really afraid to write it, in part because I was afraid that the play would then become “that play with the nudity” and that would flatten out the conversation around the play and make everything else feel less meaningful. But actually, that hasn’t happened at all, which I’m really happy about. Sometimes people even forget there was nudity, or they talk about it in a way that’s just part of the story. It’s not the reason we’re telling the story, and it’s definitely not the most important part of the story. Although to me, it is a really integral moment of bravery, and something transgressive happens there in terms of just seeing women’s bodies in a way that’s not sexualized or gratuitous or titillating.

ALLEN: For sure. I love that scene.

WOHL: Thank you so much.

ALLEN: Okay, you have six seats. Who’s in your dream-consciousness raising group?

WOHL: Well, will you be in it?

ALLEN: Sure.

WOHL: Okay, that’s one. I think we would have a fun consciousness-raising group. Do you have thoughts?

ALLEN: Is it good to have polarizing people? Should we have Candace Owens?

WOHL: I don’t know. I’m all for chaos.

ALLEN: Monica Lewinsky.

WOHL: Ooh, yeah. Now I’m thinking about women through history who need their consciousness raised. Can we get Marie Antoinette? She probably has some interesting things to share. Could we get Cleopatra? I mean, I would love to be in a consciousness-raising group with Cleopatra. And then Ithought we should have Oprah there just to make sure that everyone’s—

ALLEN: Ordered.

WOHL: Oprah will keep us focused and on track.

ALLEN: And what about Princess Diana?

WOHL: That’s a good one. I would like to hear her chat with Cleopatra and Marie Antoinette.

ALLEN: And me and Candace Owens and Monica.

WOHL: We need someone who can cook.

ALLEN: Brooklyn Beckham. He’s a chef.

WOHL: Perfect. Done. This is going to be such a good group.

ALLEN: My last question is, what do you want your daughters to know about feminism? Do you think they’ve learned anything from Liberation?

WOHL: Do your daughters like your work? Do they listen to your work?

ALLEN: I don’t think that they’re comfortable giving me praise around it. They’re 13 and 14, so they’re obviously morbidly embarrassed by the fact that I even exist. But I think more than anything, when I was going through my most recent divorce, things felt really, really bleak. And when I was in that really, really dark place, they would come home from school and I would be in bed and in tears and things felt pretty apocalyptic to all of us. And I was very adamant. I was like, “I promise you I’m going to get to work, and I’m going to get us through this and it’s going to be me that makes sure that we’re all okay.” And I think that they were dubious about that at the time because they hadn’t really seen me be capable of doing that. And now they have. So I think that’s their feminist takeaway—that mom got us through this, and Mom’s putting a roof over our heads, and Mom has to go to work.

WOHL: I think mine is similar. I think my kids are horrified by me in a certain way, because 13-year-old girls are horrified by their moms a lot of the time. But it’s just the fact of making it—the fact that I put myself out there and am doing something that’s in the world and involves some bravery and some risk—is what they receive more than the content of the work. They couldn’t care less about the play itself, but the fact that I’m making something, that’s the part that I hope resonates with them, because I hope they do that too in whatever way they want to.

ALLEN: Yeah, same.

WOHL: Lily, what is happening out there in Mexico? Are you writing?

ALLEN: I’m doing a remix version of the album, which is just different female artists taking each one of the songs. And then trying to come up with the start of a new record, which is impossible because I don’t know what the fuck to write about. But, you know…

WOHL: Really, really, really hard. Anyway, thank you for doing this, Lily. So good to see you again.

ALLEN: You too, Bess.