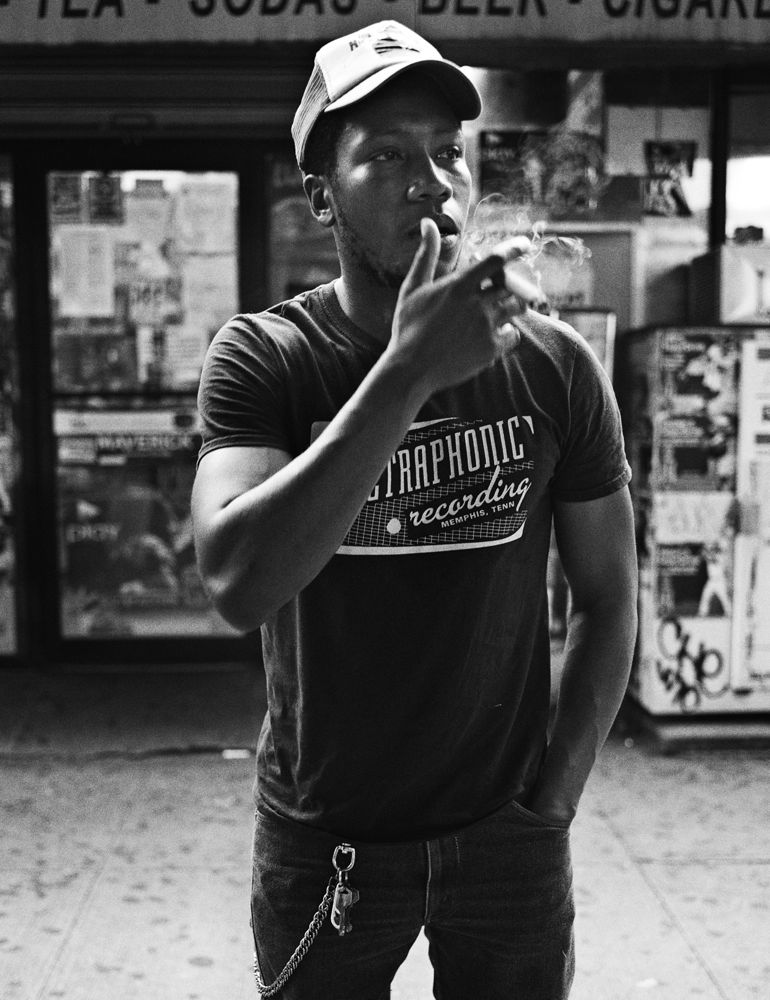

Willis Earl Beal

ABOVE: WILLIS EARL BEAL IN NEW YORK, JULY, 2013. ALL CLOTHING AND ACCESSORIES: BEAL’S OWN. STYLING: VANESSA CHOW.

“Sometimes I’m walking down the street and feel like a potential sociopath,” explains Willis Earl Beal over a glass of scotch at a hotel bar in midtown Manhattan that he chose, but which he has already acknowledged is out of his price range. “It’s not because I’m an artist or anything like that,” Beal continues. “My struggle is a human one, not the struggle of an artist.”

Beal has endured his share of adversity over his 29 years—a discharge from the Army due to stomach spasms, stints in the hospital, homelessness—all of which led him to start writing music. Beal recorded songs about loneliness and malaise on an old karaoke machine and burned them to CD-Rs that he would leave around his hometown of Chicago, along with earnest hand-drawn flyers introducing himself and inviting girls to call him. After one of the flyers was published in 2009 by Found Magazine, Beal compiled 17 of the 100-plus original songs he’d recorded into a debut album, Acousmatic Sorcery. Originally released in a limited edition by Found, it showcased his classically soulful vocals to haunting effect and garnered enough attention to warrant a wider re-release on the XL Recordings imprint Hot Charity last year.

While Acousmatic Sorcery was an eerie, super-lo-fi affair, Beal’s sophomore effort, Nobody Knows (Hot Charity), out this month, benefits from the lush production values now at his disposal. The album displays a sophistication that belies Beal’s modesty—and stubbornness—about musicianship. “I tried to learn guitar and got bored with it,” he says. “I’ve decided to never, ever learn music.” Though Beal actively resists the comparisons that plague him—to the Chicago blues tradition, to Alan Lomax’s field recordings, to other outsider-y troubadours like Tom Waits—it’s hard not to think of all three when you hear the richness of his voice, variously stark and clear or fuzzily distorted, layered against the album’s languid melodic lines. The record’s title is also a double entendre: “Nobody” is Beal’s musical alter ego, designed to personify his discomfort with the artistic process. “I don’t feel largely responsible for the songs,” he says. “I just feel like a vessel.” Rather than enjoying the spoils of rock-‘n’-roll, though, Beal says his goals are more existential. “I just want people to think about the fact that they’re human,” he says. “It’s not that big of a deal—it’s not lies and truth and righteousness. Just understand that when you listen to my music that I’m human, and I’m going to do very human things today.”

ALEXANDRIA SYMONDS: I’ve never been here before. I’m not fancy enough.

WILLIS EARL BEAL: Right, I told them, “Man, let me see if I can get some lunch out of this,” because I can’t afford to come here. I know Woody Allen plays here in a band. I’ve never seen him.

SYMONDS: I think the only people who can afford to see Woody Allen are as old as Woody Allen.

BEAL: Yeah, he knows that, too. That’s why he charges so much.

SYMONDS: Where do you live? Are you still in the city?

BEAL: Yeah, I’m still living here.

SYMONDS: What neighborhood?

BEAL: First and 71st.

SYMONDS: Oh, so you’re not too far away. Do you like it there?

BEAL: No, I don’t like living in New York at all.

SYMONDS: Really? Are you thinking about leaving?

BEAL: I’m definitely going to leave. I want to leave. I want to go Washington state.

SYMONDS: What about Washington state appeals to you?

BEAL: It’s gray, and there are trees. I like that kind of stuff. There are far less people. I feel totally disconnected from reality in this city. Maybe I’m just really pretentious—in fact, I probably am—but I feel like people in this city have no idea about where their reality is coming from and who is helping them to live in this illusion. [I’ve gone] from the south side of Chicago, where everyone is completely unrealistic about what’s important in life to a place like this, where people are still unrealistic about what’s important, but it’s on two opposite sides of the spectrum. I just get tired of it all. It makes me really, really angry. [laughs]

SYMONDS: I know how you feel. Were you expecting something different when you moved here?

BEAL: It was kind of by accident. I never really intended to live here. I’ve always been passing through ever since I left Chicago. I haven’t really settled down yet.

SYMONDS: Do you think that you’re destined to be a nomad forever, or do you eventually want to have roots somewhere?

BEAL: Yeah, definitely. I’m interested in getting a place somewhere and staying there for the rest of my life. Just like J.D. Salinger did. He lived in his town and nobody messed with him, but they all knew who he was.

SYMONDS: I wonder if that’s it’s own kind of absurd way to live. He couldn’t leave the house without people talking about the fact that he left the house.

BEAL: My only goal from the beginning—since I graduated high school—was to just get a place and live there and have a lady. Just to have stability and a means of making money and things like that. As far as trying to make it terms of social hierarchy or status and all that in art and music—I’ve always felt that that stuff was bullshit, but it was interesting to me from a purely superficial standpoint. It’s just something I always thought about as a novelty. It’s got very little to do with reality, and reality is where things live. You look at a painting and you think, “Oh, well, it’s beautiful. It inspires me,” whatever. But it’s never going to inspire you like reality. I think that a lot of these artists and musicians who prioritize skill over experience, they sit around masturbating themselves over knowledge and intellect rather than just going to a place. For me it was always just this thing that you get involved in for a while, see if you can make a few people be interested in you, then you milk it and you move on.

SYMONDS: When Acousmatic Sorcery came out, it was an anomalous record to become as successful as it did. It was not originally meant as something for a lot of people to hear.

BEAL: That’s what I wanted and what I envisioned. When I recorded those songs—that was 13 out of 150. What I envisioned was somebody walking along the street picking it up—that’s it. That would’ve been satisfactory to me. I wanted to get invited to a nice party and see pretty girls, drink some alcohol, and smoke marijuana and have that be the end of it. I always had a difficult time relating to people. I just wanted to be thought of as an interesting person—nothing more.

SYMONDS: Did you want people to hear the album without context? It seems like if you’re leaving it in places, that’s what you would want. So for people to listen to it because they read about you in Complex, is that in some way different?

BEAL: I used a pseudonym back then. I just wanted to be some mysterious guy. But then they marketed me in some eccentric Alan Lomax field recording [way]. If it hadn’t been for Jamie—James Medina, the founder of Hot Charity, I wouldn’t be here. So I thank him. He’s also the one who took those pictures of me that look like Robert Johnson or some shit. Yes, they’re high-quality pictures, but I never wanted to be like that. Coming from Chicago, everybody makes that association between me and Chicago blues. But, I don’t give a fuck about Chicago blues, nor do I care about any region for that matter. I was only concerned with my own dreams—being totally selfish and completely iconoclastic. I just grabbed onto things, it wasn’t an association between this historical stuff. It’s really disenchanting that just because you look a certain way or sound a certain way, people just want to put you in a box. As a result of that, people are actually disenchanted by the way the record sounded. It wasn’t meant for them anyway.

You have critics saying, “Wow, this was intentionally lo-fi.” I couldn’t afford better equipment. It was not intentionally lo-fi. I’m happy to talk with you in Andy Warhol’s magazine about something I’m really proud of. Because I feel like now I can get the respect I finally deserve. Even if they don’t respect it, I know that I gave 100 percent. It’s just a record at the end of the day, but it’s 29 years in the making—it’s my life, my dreams, my struggles—it’s everything that I am. I think if you can do something like that, then you’ve won a hundred times over. It’s gonna get released, and people are going to love it or hate it, and move on to the next artist. I’ll always have it in my iPod and have it on my shelf. I had a chance—I had a shot.

SYMONDS: How much of the material here was from the time in your life leading up to Acousmatic Sorcery, and how much of it since? Do you think that you need a lot of time and space to process what happens to you, and that it will be a long time before we hear the songs about the most recent years of your life?

BEAL: I’ve actually got a whole other record, but those are all old songs, too. I wrote so many songs, so I’ve got a lot of material to work with and I can draw from that. Some songs are pretty immature and not really thought out. So I can just use that and reapply it to my current life. I’m really fortunate in that I got a lot of shit archived. I’m happy about that—I don’t have to do too much thinking.

SYMONDS: It seems like you do a lot of thinking anyway, though. [laughs]

BEAL: Yeah, well, I’m not really a productive thinker.

SYMONDS: Is there such a thing as a productive thinker?

BEAL: Yeah.

SYMONDS: Who’s a productive thinker?

BEAL: Jamie—James Medina. He’s constantly thinking about ways to promote people and their next project. I feel like I really haven’t contributed to my own life, or I feel like a contributor to my own life. I don’t feel like…

SYMONDS: The principal contributor.

BEAL: That’s why I put that this record was produced by “Nobody”… I haven’t done anything in 25 or 26 years, and I’m just kinda moving through. I drive people crazy because I’m always trying to poke at things to make sure that they’re alive. There are so many other people who are actively playing shows every night, and they ask me, ” Well, what do you do?” And I say, “I’m a musician.” So they ask, “What do you play?” And I say, “Everything and nothing.” So I feel pretty disconnected from things—I’m just floating, and everybody else is on the ground or in the sky.

SYMONDS: Have you met anyone who seems to feel the same way about their musical careers the way you feel about yours?

BEAL: Cat Power seems to feel the same way.

SYMONDS: When you say, “Something like a vessel,” what is it that’s acting through you—is it something inspirational, or something different than that?

BEAL: Pure darkness. And when I say darkness, I don’t mean evil or anything, but space and time. I hope to transmit that through my rudimentary compositions and words. I feel like too many people think that their lives are the know-all, be-all just because they went to India for four weeks and they stood on top of the Holiday Inn and looked down at the Ferraris and naked children, and they feel like, “Oh, that’s life.”

Honestly, human beings aren’t much. They never have been and they never will be. The things that we’re doing are not really relevant or important at all in the face of reality. Reality extends far, far beyond the world. All of the wars, disputes, people on Fifth Avenue, or people in the ghetto—they all think it’s so fucking serious. What I’m trying to do is paint a picture of an atypical human being going through all of the existential struggles, but all the while realizing the carnality and small things, because I like minutiae a lot. All the while knowing that it’s a forest—knowing that none of it means anything. That’s what I’m a vessel for— reality. I think if more people understood that, they would just either go ahead and kill themselves like they’re gonna do anyway, but do it quickly as opposed to hanging out and using up resources; or mean something, make things matter. Don’t just fucking sit around criticizing other people and wasting time. I do that a lot, but I’m not really skilled in any other way.

SYMONDS: I think that in order for most people, to walk around the world and drink scotch and put on clothes in the morning—you have to find some balance between acknowledging that and forgetting it. Do you feel like that’s a struggle in your life?

BEAL: Yeah. I think, “Maybe you’re crazy.” But I’m not crazy, I just haven’t figured out how to do anything yet besides recording music—I don’t even entirely know how to do that. My favorite phrase is “It takes a lot of imagination to have no talent.” So it’s a struggle because I struggle between thinking about whether or not I’m actually a musician, am I actually an artist. Does it matter what I’m doing? Should I just go and jump off a bridge? And also, there’s lust. I’m sitting in the square and looking at ladies pass by and I’m thinking, “Why can’t I just grab that ass? No, I can’t, that’s wrong.” Thinking about the social hierarchy and the fact that I’m American, and how I don’t identify with being American, nor do I identify with any nationality or my race. Then another struggle that I have is I’m a glutton. There’s always those very simple, long, old-ass things, but they’re very real to me, and I’m sitting in them, and they’re swirling in my mind all the time. I tell people about it and they think, “Well, why don’t you just go and make some money, go get a big-screen TV, or look at the Internet, or just go masturbate.” Or they say, “Go create some introspective art.” I just want to explode, you know what I mean? I don’t know what it means—I don’t know why I’m like that. I don’t know how everybody else is able to walk around so calm. It’s amazing to me when I see people walking so calmly down the street. I envy them, but I also kind of hate them.

SYMONDS: Do you think it’s possible that maybe you just can’t read into their expressions what’s going on behind them? You look very calm right now, and you’re describing something very vividly that isn’t. But you’re not yelling at me; your face isn’t screwed up into a mask of fury or anything.

BEAL: I’ve been trained very well. They train us to have the right gesticulation—that’s why I feel like I’m acting. It just so happens that the reason why I’m here talking to you, is because it was all utilitarian—it was all like taking out the garbage. If I hadn’t written these songs down, I’d be another casualty at war. It’s got zero to do with delusions of grandeur or glory. As romantic and ridiculous as this may sound, hopefully these songs can bring me some kind of salvation—to give me that ever-present cabin in the woods. I can chill out on my own land and have a chain of dry cleaners and become a fat man. I’d be respected in the world. I’m kidding. [laughs]

SYMONDS: You’ve said several times that you don’t think you’re talented.

BEAL: I’m a fucking X Factor contestant, all right. I can sing good. I’m not trying to be modest but I can sing good and I’ve got a sense of rhythm. I’ve got some talent. You’ve got magicians, you’ve got guys that play three-armed guitars—you have all sorts of people with talent. It’s negligible.

SYMONDS: I guess the question I want to ask then is whether or not you think there’s any responsibility to talent. I think that we tend to think of talented people as being very lucky, but I also think it’s possible to see talented people as being very burdened by that. Maybe you think of your life as having more possibilities when you aren’t able to recognize this one thing that you’re really good at.

BEAL: I don’t think talent really has anything to do with anything. I don’t think talent has anything to do with inspiration. Inspiration creates talent. I think that people prioritize innate talent too much. It gives them license to walk around and act like assholes. I’ve experienced that firsthand. I think I straddle a line between being innately talented and having had to put in some work. I can kind of see both perspectives. You ever go to a party where there’s supposed to be a lot of creative people—a lot of artists and stuff like that—and they feel like they have license to just act any kind of way? I’m not really a moral person myself, I don’t believe in good and bad, but they just tend to never ever be sincere because they believe somehow their art or the fact that they are artists makes them holy in some way. It’s another form of work—it’s not holy. I’m making music at this time in my life—maybe my music will inspire a surgeon while a surgeon is working on a person. Everyone’s just putting in work. Everything is the same.

I’m glad that this is happening for me, but I hope it doesn’t go to my head, and I hope I can make enough money to protect my being, because I see a dark cloud when I go to my own shows and people are looking at me rather than listening to the music. They’re thinking about my personality as opposed to the concepts that I’m trying to give. It’s nice—it’s cool when you have pretty ladies looking at you. Real nice. It’s what I dreamed of. But after they finish looking at you, you wonder, “But did you understand? Did you get it? Was there anything to get? Am I full of shit? Let me know.” People don’t have the ability to do that because they’re too enthralled with being in a situation where they’re looking at someone who’s elevated above them physically. There’s so much of our culture that’s poison. Hopefully I can become an insurgent and hold up the “Nobody” flag and say, “Now you see me? This is what I really am.” It’s like a mirror reflected back to people. I’m at these festivals watching these guys with these long cocks in their hands… [mimes playing a guitar] maybe that’s not where it’s at. I talk a lot. I would talk to myself if I could. I’ve interviewed myself 11 times.

SYMONDS: Has any of that gotten printed?

BEAL: No, that stuff’s gone. I used to write it down in the bathroom. I’ve already retired a couple times. I’ve had some greatest hit albums…Is this hard for you? Doing interviews and getting people to talk to you about their philosophy all the time?

SYMONDS: It’s both hard and wonderful. I’m very curious about people, and one of the most difficult truths for me to accept as a person is that I’ll never be anyone else, and I will never fully understand anyone’s perspective other than my own. Because I’ve come to some understanding of that, I feel it’s this very difficult but worthwhile challenge to get as close as I possible can to that. If the only way that we can do that is through language, then that’s how it has to be done.

BEAL: Has it helped you as a person?

SYMONDS: I think so. I used to be very shy, and I don’t think I am anymore. I think being able to ask people questions about themselves that don’t upset them, hopefully, is a better way of learning how to relate to people.

BEAL: I’ve been interviewed a great deal, especially in the last month. I went to Belgium, I went to France, I went to Amsterdam —and these people, they interview you and they’re so interested in what you have to say, and if they’re not interested they make a damn good show of it. It always fascinates me how you can get so much joy listening to another person, when me, personally, I can only listen to myself and my music these days. I’ve got some people in my iPod, but I only listen to myself. I’m folding into myself and I used to think that that was what you’re supposed to do—you’re supposed to reject everyone else and figure out who you are. You get little shards and points of reference, but that’s how you confirm that only you know what is right for you. Everything else is pollution. What’s starting to happen to me is sort of an identity crisis.

I think I envy the interviewers because they can digest all these things, and I know that they’re using it and they’re looking at these people like myself and going, “Okay, I see it. It’s my work. I’m getting paid for it.” And they also use it as a point of reference, like, “I’m so glad I’m not an artist.” What I wouldn’t give to be comfortable. That would be wonderful, to be able to look at people and be this cipher and just ask questions. I don’t know anything about you or about doing interviews, but the artist just guts himself or herself and the interviewers are full all the time. I know that they are—they have to be. They probably get filled up. Is that true?

SYMONDS: Yeah, I think that is true—some of the time, at least. If you weren’t being told that this was part of the way to promote your album and that you’ll get more exposure if you do press, would you do it? Is there something worthwhile in this process?

BEAL: I talk all the time, and I’ve always taken every opportunity to talk to people. But initially it wasn’t. Prior to all of this happening, when I first distributed those CDs and those drawings and those scenes—I put my phone number on them because I wanted people in the neighborhood or the town to call me. Honestly, this whole thing has been about communicating with people. As much as I like spending money, what’s at the other end? Some object or some perishable—whatever. But the relationships that you form with people, whether they be temporary moments or telephone conversations every week—they’re the things that create life.

If the only thing that you want to do is make money—if that’s your whole motivation—I think you’re lying to yourself. If the only motivation you have is to make money and make it, what’s making it? Oh, you get a yacht or an island. Well, you’re going to need someone to be on that island. You’re going to need people, one way or another. Sometimes I wish it were a simpler world. I love and hate people. When I say I hate people, I really truly mean it. Sometimes I think everyone should be dead, that the animals would be better off without people. But sometimes I go into the square and I look at all the people passing me by and it fulfills me—as long as they don’t bother me. As long as they just walk past and don’t ask me for anything, it’s fine. I almost wish I could think about it in a mundane way.

SYMONDS: What do you think are the ideal circumstances for someone to hear your songs? Most musicians that I’ve talked would say that they feel the most pure as musicians when they are performing live for other people, as opposed to when their music is heard on headphones. But it almost seems like you’d think the best way to listen to your music would be in a sensory-deprivation tank, where the only thing that’s happening is hearing the music.

BEAL: Yeah. Actually, that sounds cool. I think the best way to listen to my music is through recording. I would love to be one of those artists where you can go into a coffee shop and watch people pass by and then my music is in their ears. Not necessarily a sensory deprivation thing, but that’s cool too. Unfortunately in order to focus on nobody else, you would probably have to go into a dark room and just sit there and listen to it.

I think that live music is really pretentious—all of it. I hate festivals and live shows, because as soon as I get on stage, I start performing for people and it becomes about sex, banter, and skill. They’re looking at me and not thinking about themselves. I’m thinking about how cool I look. It’s just stupid—all live music is really stupid. I wouldn’t encourage going to see anybody live, ever. Not even me. But unfortunately, I’m going on tour now, so it’s like “Come and see Willis Earl Beal on the Church of Nobody [tour].” I need to promote this, because that’s how I’m gonna get the cabin in the woods. So it’s a constant battle.

NOBODY KNOWS. IS OUT TODAY. WILLIS EARL BEAL IS CURRENTLY ON TOUR IN EUROPE. FOR MORE ON BEAL, PLEASE VISIT THE ARTIST’S WEBSITE.

GROOMING PRODUCTS: DIOR HOMME, INCLUDING DERMO SYSTEM REPAIRING MOISTURIZING EMULSION.HAIR PRODUCTS: KEÌRASTASE, INCLUDING BAIN CAPITAL FORCE ENERGETIQUE. HAIR: JENNIFERYEPEZ FOR KEÌRASTASE/MAREK AND ASSOCIATE S. GROOMING: KARAN FRANJOLA/MAREK AND ASSOCIATES. SPECIALTHANKS: FAST ASHLEYS.