q&a

Patti Smith Is Always Going to Be a Worker

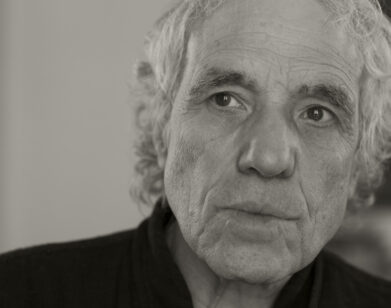

Patti Smith circa 1969, photographed by Judy Linn.

Patti Smith needs no introduction. Seriously. The iconic American musician, poet, and photographer has a new, in-depth music project—a result of her years-long collaboration with the experimental New York City-based Soundwalk Collective to create a triumvirate of records rooted in the poetry of some of the world’s most renowned authors. The three records—2019’s The Peyote Dance, based on the work of Antonin Artaud with a guest spot from actor Gael García Bernal, and Mummer Love, from Arthur Rimbaud; along with 2020’s Peradam, which lifts words from René Daumal—feature Smith improvising, reciting, and chanting amidst mesmerizing music, often based on field recordings taken from around the world. Smith, who still harbors a slight (and endearing) South Jersey accent, has been quarantined in New York City since March, and she’s going a little stir crazy. Nevertheless, she’s as wise, thoughtful and learned in conversation as ever. We caught up with Smith to ask her about her three records, our three pandemics, and everyone’s favorite trio of talking fast food cartoons. (Why not?)

———

JACOB UITTI: What is your first musical memory?

PATTI SMITH: I have many, like learning “Jesus Loves Me” or “Eensy Tweensy Spider,” but I would say the first real profound one was hearing Little Richard singing “Tutti Frutti” when I was very young, maybe 5 or 6. The energy of it just, like, got me. I didn’t know what it was. I was just a little girl, but the energy in it was akin to a child’s boundless energy. I can remember that quite clearly because I was on my way to Bible school.

UITTI: Looking to your work with Soundwalk Collective, there is a lot of chanting on the albums. What does chanting or verbal repetition do for you, creatively?

SMITH: Well, I think that verbal repetition is very akin to rock ‘n’ roll songs, gospel. But I think that within, if you’re talking about the records I did with Soundwalk, a lot of it is because they’re poems and there’s the refrains in the poetry, or it’s the way that the poet has set up the poem. Or because the music has a trance-like atmosphere, perhaps I was drawn to repetition. I can’t tell you specifically which is which, but if you broke down, say, a song like [Little Richard’s] “The Girl Can’t Help It“— The girl can’t help it. The girl can’t help it. The girl can’t help it. The girl can’t help it. The girl can’t help it. The girl can’t help it if she’s in love with me. If you’re going to read out lyrics or read poetry, there’s often rhythmatic repetition.

UITTI: A theme that comes up in the records is death. May I ask, do you have thoughts about death or the afterlife?

SMITH: Obviously, I’ve experienced a lot of loss in my life. But I don’t necessarily connect all of my personal experiences with loss when I’m reading another person’s poems or their work. I actually, truthfully, hadn’t really thought about death as being a prominent theme. I don’t think I noticed it. I suppose because all of these writers speak of transition, continual journey. It’s an energy. Death isn’t a… you don’t hit a wall. You don’t stop. It’s just part of a continuous energy. It’s into the next phase. There’s one piece on the Artaud album, The Peyote Dance, called, “Ivry,” which I wrote myself, which does speak of Artaud dying. But even that one is more like his consciousness kept walking. Artaud died sitting up, which I always thought was a very interesting thing. He had such an intense mental energy and so much mental passion that he died in a state where he might have just been ready to stand up and walk out the door. But, you know, that’s a broad question. As I said, I’ve seen enough loss in my life to be able to speak about death endlessly. But within these [albums], I think that I really didn’t have the sense of that kind of death or loss. I didn’t feel personal loss in preforming any of these pieces. I felt the continuing trajectory or the continuing journey of each of the writers.

UITTI: To record the albums, there was a great level of travel that had to take place, to get the sounds, to get the atmosphere from the locations where the poets lived throughout the world. Given that and given today’s state of travel—and the politicization of immigration—what does the idea of travel mean to you?

SMITH: Right now it’s a difficult subject because we can’t travel. My feeling about travel right now is, you know, a certain longing. I’m quite a traveler and I haven’t traveled for seven months. I had a tour canceled where I was supposed to be traveling continuously for a year. I’ve been rooted in the same spot in New York City for seven months. So, I’m more traveling in my mind. But I think about the people in the world and those having extreme strife, whether it’s right in our own country because of fires and displacement, or in Yemen or in Syria. All over the world people are being displaced because of famine, disease, war and they’re all on the move with no welcome anywhere. It’s, again, another very complicated subject. I long to travel, but I’m also very lucky to have my own place to live. Many people in the world don’t long to travel. They long to have a home. Those are the two states of mind that we’re dealing with.

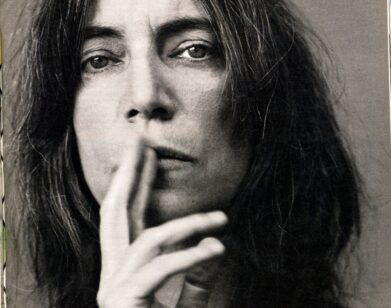

A young Patti Smith photographed by Lloyd Ziff.

UITTI: I studied poetry as a student and still write it sometimes. And to create these albums, you drew a lot from the poetry of the three past authors. At the same time, poetry isn’t always valued very highly these days. What is the value of poetry to you today?

SMITH: I’ve always thought of poetry as being one of the highest and most difficult arts. It’s very solitary. It’s often quite difficult, difficult to interpret. It contains such great beauty and cosmic or alchemical thought. Poetry is a difficult vocation. To be a poet is probably one of the most thankless ones. Very few poets gain recognition. The struggle to write poetry—I always think of Arthur Rimbaud writing A Season in Hell. He was in his family’s farmhouse the summer of 1873, and he locked himself in there and his younger sister wrote in her diary that he could be heard yelling, crying, and shouting all summer long, trying to write A Season in Hell. And he wrote it—it’s a small masterpiece —and it took it to France, Paris, and it was rejected. Ridiculed and rejected and he received no acclaim or no recognition in his lifetime. So, it’s a difficult vocation. But one, I think, that is elevated. An elevated vocation.

UITTI: When you think about the triptych, the three albums you’ve made, what comes to mind for you?

SMITH: Well, I think that the process is the thing that I think about the most, now that the albums are finished and they are designed so beautifully. Even to the point where the last record, the vinyl is blue, it’s just beautiful. But the thing that stays with me is the process. [Soundwalk founder] Stephan Crasneanscki is a hard traveler. He is an adventurer. He is a mountain climber. He goes to sacred places, difficult places, dangerous places in order to get the soundscapes and bring them back to me so that I can alchemically channel the atmosphere that these poets lived in. He went to Ethiopia where Rimbaud lived. He went to the very difficult, very dangerous parts of Mexico up in the mountains where Artaud went. And he went to treacherous mountains in India to merge Dumal’s studies. I’m quite a traveler, but I’m more of a road traveler. I travel on foot or in trains and I like to be on the move, but I like sea level travel. He is able to do the rigorous travel and bring back these musical and sonic souvenirs of each place that I can riff on and read on. It’s unique. We both bring something to the table.

UITTI: How about the “fourth mind,” or the practice you used to channel these various writers and authors?

SMITH: Well, I’ve done that all throughout my recording life. My subjects were Jimi Hendrix and Jim Morrison when we did Horses and Rimbaud when we did Radio Ethiopia. And it’s the people having bombs dropped on them in Iraq later in “Radio Baghdad,” or Gandhi. I’ve done a lot of long improvisational pieces throughout, so it’s something that I’m already adept in. I mean, I don’t have a strong point writing popular songs. I don’t have the gift for that. But I do have the gift of improvisation and the sense of channeling things. I used to speak with William Burroughs quite a bit about that process. So, it’s a continuation of what I’ve always done except what’s new about it is the site-specific work and the fact that there’s just the two of us and a lot of it depends on great study. Really in-depth study and reading and being interested in the same kind of thing. So, I’m working with a person, we’re in tandem. We’re of like mind. We create the third mind. Where the fourth mind is, I’m not sure. But Stephan and I create the work together. The process might be the third mind and the work itself might be the fourth. I’m not quite sure. [Laughs] But it’s a very rewarding process.

Photo by Lloyd Ziff.

UITTI: I’m going to push back and say you do know how to write a hit song. You wrote that hit for the cartoon Aqua Teen Hunger Force, remember?

SMITH: [Laughs] That giant hit!

UITTI: What is your relationship to that show? I ask because I love that show, and I actually interviewed the creators because there’s an anniversary coming up.

SMITH: Oh, wow, you did? Lucky you! If you send them an email, or something, tell them I’m still watching Adult Swim reruns of Aqua Teen Hunger Force on demand. I love them. I’ve always loved cartoons ,since I was a kid. I used to watch Ren & Stimpy when my children were little. But my son Jackson and I have an affinity for very similar shows. We like anime and we talk about that stuff. Some years ago, he said to me that I should watch this Aqua Teen Hunger Force, that he thinks I would like it. I had never heard of it and I watched one episode, and I was dying! I love it so much. I was totally hooked. Then I guess I wrote about it on my website or something and they contacted me and I was thrilled! My son and I met them! It was like meeting your favorite movie star to meet these people. When they gave me the opportunity to write that little song… what is it, 27-seconds long, or something? I’m trying to remember how it went.

UITTI: It was like, “It’s the end of Aqua Teen… Master Shake… Meatwad the floating head… now they’re dead!”

SMITH: [Laughs] Yeah, now there is a moment of death! There is a death throw in the Aqua Teen Hunger Force song. But I just love them. I love that show. It’s a certain kind of intelligence. I can’t even explain it. Also, I’m from South Jersey.

UITTI: Me too! Well, actually I’m from Central Jersey.

SMITH: Well, I’m all the way down near the Woodbury area, which is souther than Camden, going towards the shore. And I think [the Aqua Teen creators] are from Runnemede, which is south but not as south as me. But I was so thrilled that they were, you know, from South Jersey. I don’t know if it’s a joke or whatever, but South Jersey is mentioned! You’re the first… no one has ever. The fact that you asked me is just so much fun. I loved writing that little song. It was a big honor for me to write that little song.

UITTI: The show is so quick-witted and so comforting at the same time.

SMITH: And so obscure! [Laughs]

UITTI: What do you want to talk about? There’s, of course, lots to talk about. There’s your seminal album, Horses, COVID-19, punk rock, social justice and the Black Lives Matter movement. What is on your mind these days?

SMITH: Those are such important matters. We have multiple pandemics that we’re facing. We have the COVID virus, which affects us all. Everything does. The systemic racial pandemic that we have never totally, haven’t even come close to really wrestling down, to really make great change in the consciousness of our country. And the umbrella over everything is the climate change pandemic, which might be actually the one that is the most disturbing and the one that is going to affect us all in the coming years. To me, they’re all emergencies. There’s so many things that we have to deal with. The people of the world are suffering. And because of climate change, they’re suffering the greatest locust infestation, billions of locusts in certain areas where the people are experiencing famine. In Sudan, people are basically drowning due to flooding. You have famine on one hand and drowning and disease [on the other]. People looking for a new home, looking for bread, looking for safety for their children while dealing with the threat of the virus. We’re living in such historic times. What we’re faced with as human beings, it’s overwhelming. None of these things can probably ever be solved. You can’t talk about these things as solving them. You talk about lessening the burden. You talk about awareness. You talk about making things better. Global unification. The unification of people. Is everyone on the same page? Everyone sacrificing to bring our carbon levels down, everyone sacrificing and educating themselves about who we are as human beings. And that’s very hard in our present climate when our present administration is all about division. We’ve always been somewhat divided as a country, but somehow, in a certain way, coexisted. I’m going to be 74-years-old, and I’ve never seen a more divisive time. The only way that we’re going to save the earth, save the species and evolve on a higher ground in terms of race is unification. Is everyone deciding that we want to do better? It’s that simple. It’s just that we want to be better people. That we want our air quality to be better. We want our citizens to be happier. We want them to feel safer. It’s just all we want. The bottom line is, we just want things to be better and more equalized. I’m just trying to educate myself every day. Learn everything I can and try to develop a greater sense of empathy and also take care of myself. That’s what we have to do. Stay healthy and stay prudent and stay aware and do better.

UITTI: How about the Grant Hospital of Chicago, where you were born? Have you thought about that place at all recently?

SMITH: Well, [Laughs] I went to see it. But in 1946 it was a very small hospital. Very small, very pretty hospital. Now it’s a giant complex. But what was funny about it was my father’s name was Grant. And when I was a little girl, he used to tell me that, because there was a picture of Grant Hospital on my birth certificate, “Yeah, that’s my hospital! See, it has my name on it.” We always had money problems. My parents struggled. My father worked in a factory, my mother was a waitress. And then they’d say something like a rally or some thing in Grant Park. And he said, “Yeah, that’s my park, Grant Park.” And I would think, “How come Daddy has this big park and this big hospital and they’re having so much problems, financially?” But the beautiful thing is I got to, in my father’s lifetime, play with my band in Grant Park. I was very proud to play in Grant Park. And I called my dad and I said, “Daddy, I’m playing in your park!”

UITTI: What do you think about when you hear the name Patti Smith?

SMITH: Truthfully, I think of myself as a worker. Even when I was young… I remember when I did my first poetry reading, I didn’t write “Patti Smith, poet.” I wrote, “Patti Smith, worker.” Because that’s what I feel I do. I have multi-disciplines. I wouldn’t say that I’ve ever been a prodigy, or anything. I have to work very hard at all the things that I do in order that they might be of worth. That’s what I think of myself as, a worker. The nice thing about that is you can be a worker for as long as you live! So, I never have to retire. I’m always going to be a worker.