PUNK

“I Don’t Respond Well to Rejection”: One Hour With Richard Hell

When I moved to New York City in 2010, my first purchase at the St. Marks Bookshop on Third Avenue was Richard Hell’s 2005 novel, Godlike. Had the original punk rocker traded it in to become a great novelist? First issued by Dennis Cooper’s Little House on the Bowery imprint for Akashic Books, Godlike quickly became a lodestar for the life I wanted to live. Following two young poets who mirror Paul Verlaine and Arthur Rimbaud, transposed to the artistic scene of ‘70s Lower East Side, it is dense with sensation, action, thought, and location in the way good fiction strives to be. Unassumingly brief, with a low-key Christopher Wool cover photograph anchoring you in place and time, it’s loaded with at least as much creative energy and philosophical depth as his classic albums Blank Generation and Destiny Street, all of them part of a larger, innovative, aesthetic discipline under whose sign we still live.

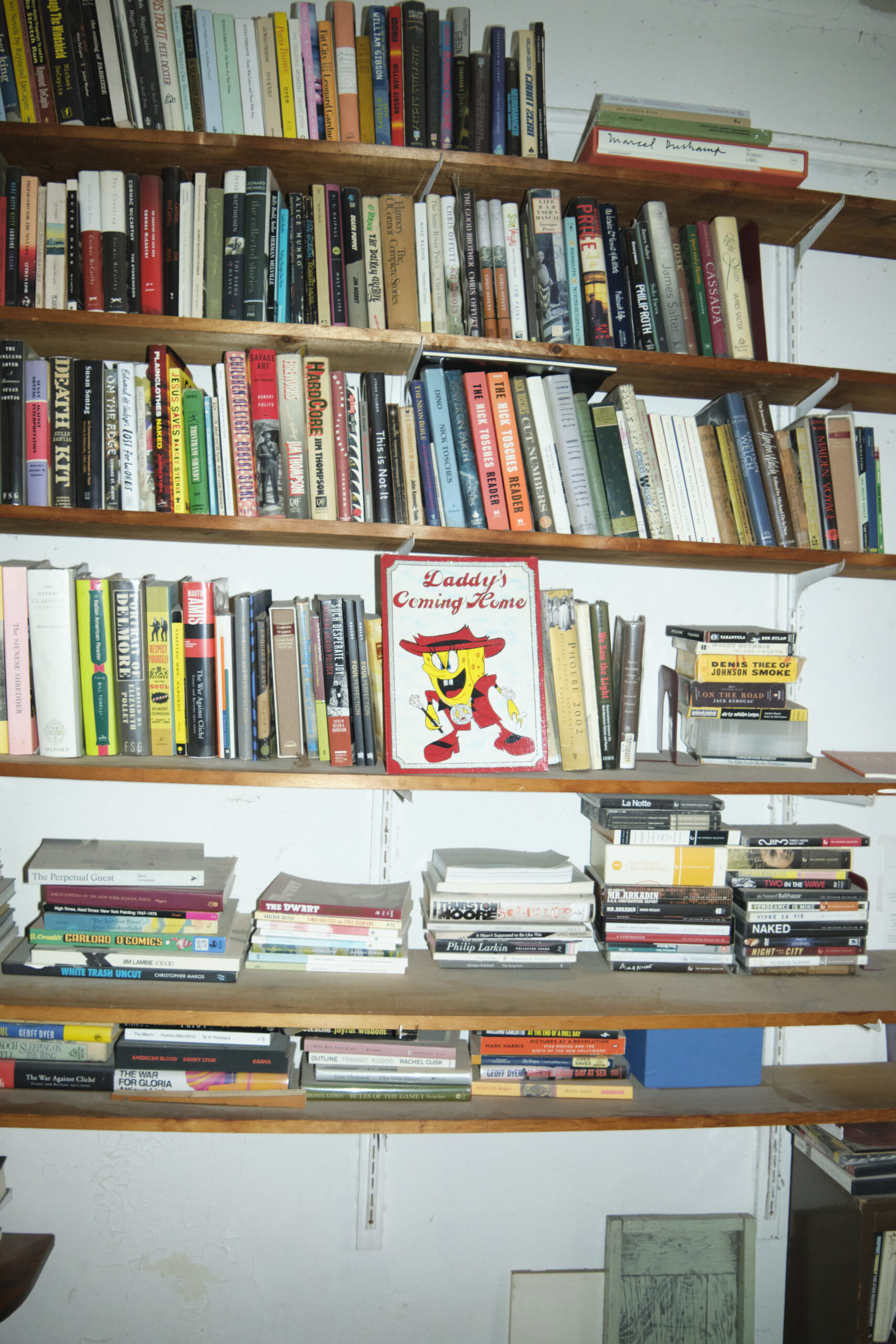

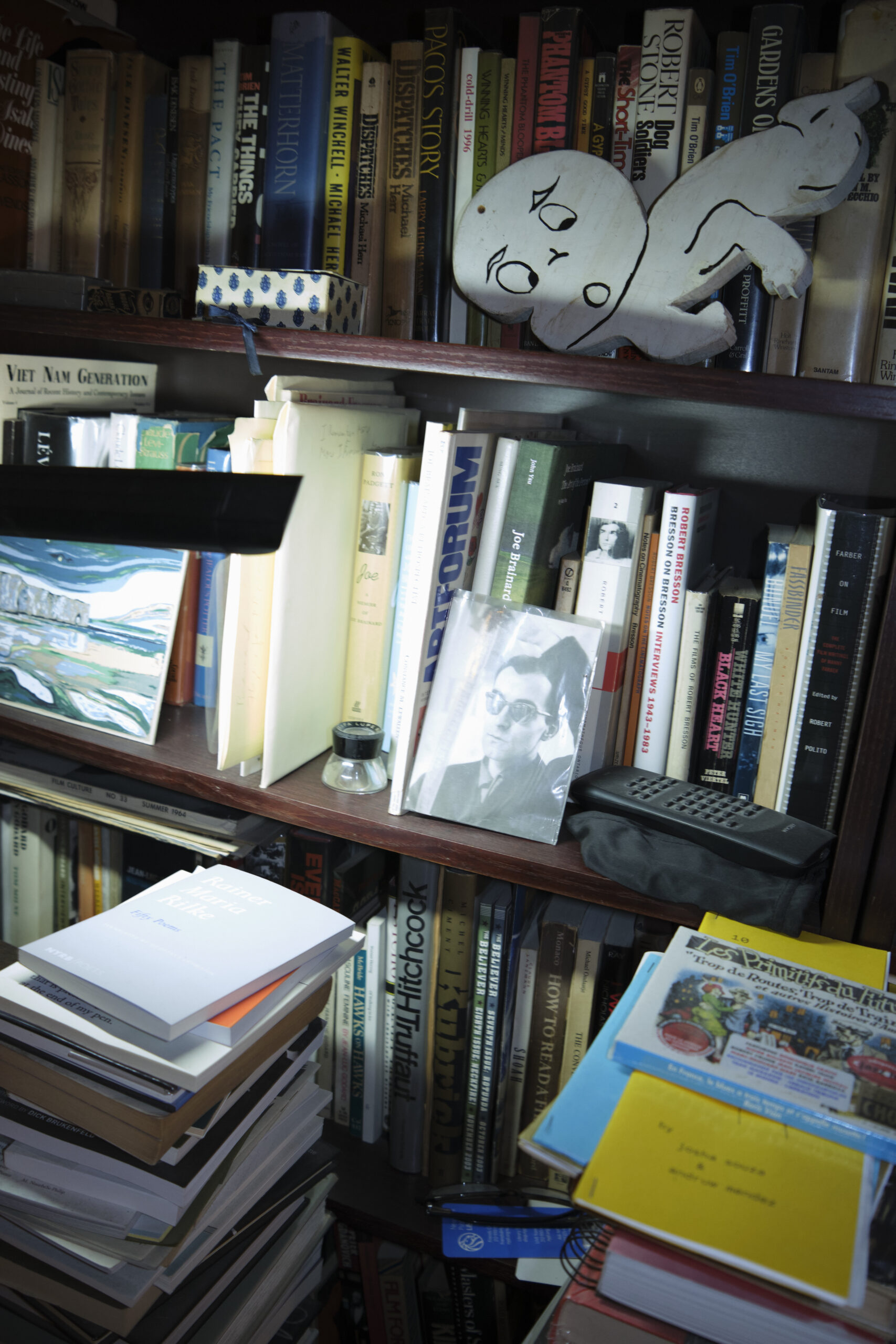

As the one-time publisher of Archway Editions (and a new company launching soon), I’ve regularly met with Hell to talk about his projects and the literary scene over at Knickerbocker Bar & Grill on University Place. For this interview, though, I joined him at his apartment nearby. He’s lived there since the ‘70s, and it resonates with the historical warmth of an old tenement. The hallways outside were dusty from the landlord renovating to jack up the rents, but inside there was coffee on the stove, a clawfoot tub in the kitchen, and Nan Goldin’s cover photograph for his novel Go Now framed on the wall. I caught him, as usual, in the midst of a bout of infectious artistic enthusiasm; in this case, choosing an original R. Crumb drawing on which to spend hard-earned savings. As we talked about his work and influences, he’d periodically disappear into a converted second bedroom to fetch more books and zines, including the original edition of Godlike. Long out of print, a reissue of the novel will be published this week courtesy of Edwin Frank at New York Review Books, with an afterword by Raymond Foye and supplemental notes, orienting generations of future readers to Hell’s singular work.

———

RICHARD HELL: There’s your coffee. Do you take milk or sugar?

CHRIS MOLNAR: No, that’s alright.

HELL: Cool, all right. Let’s get going.

MOLNAR: Well, you’ve talked about how, with Godlike, there was this idea of people reading too much into Go Now as a part of your life, and trying to scramble it so it was further from your life.

HELL: I mean, part of the direction I went in writing Godlike had to do with me reacting to criticisms of Go Now. I don’t even know if I should dignify it as a criticism, but people would treat it as if it wasn’t legitimately a novel because it was me, as if it was autofiction. And that was untrue; I made up the story. I used an experience I’d had to give me a structure or to actually enable me to dispense with structure, because that first novel was based on a commission I got to drive across the country in 1980 in an old Cadillac and write about the experience which took place. But I was too strung out at that time to produce the non-fiction book that the guy was commissioning. It was supposed to be just about me with the photographer Roberta Bayley driving in this Cadillac cross country in 1980, her taking pictures and me writing notes. I used that as the premise for my first novel, Go Now.

My only objective was to talk about what it was like to be a heroin addict because I hadn’t read a book that described it the way it felt to me. But I needed a story, and I’d had that experience maybe 10 years before I started writing a novel. I thought, “Oh, that’s a good setup for talking about this thing, the psychology of a drug addict.” I’m not much with plots, so using that story was basically just to give me a plot, or as I said, free me from plot, because a road novel makes its own plot. It’s going from place to place. I don’t have to come up with anything, it’s just incident after incident after incident, like picaresque.

Anyway, this is a long digression, but people would dismiss it as me just writing about myself and I kind of resented that. So when I was ready to start writing Godlike, I knew I wanted to write about poets, just like the first book was me wanting to write about being an addict and what that meant. I wanted to talk about poetry as your driving force, as your, as they say in French, raison d’etre, your reason for being. But then I thought, “Okay, how can I make it as extreme as possible so nobody can say he’s talking about himself?” So I made it about gay poets on acid instead of womanizing punk musicians on heroin. Though, of course, as it turned out, they still accuse me of writing about myself. But it was also super fun to have [Paul] Verlaine and [Arthur] Rimbaud’s lives as the bones of the story, but set in the New York that I knew and its peak period of wild and creative squalor in the early ’70s. It had all these fun aspects to it to keep me engaged and interested.

MOLNAR: And again, the reader is aware that you were around back then, but how much of the scene that you’re trying to describe were you actually participating in?

HELL: Well, I came to New York to be a poet when I was 17 and I started a press. I bought a printing press and a little tabletop that cost $300 to bring out magazines and broadsheets and little pamphlets, but I didn’t really have a community. I wasn’t part of a scene. I learned about St. Mark’s pretty quickly, and that’s where everything was going on. And I really liked their publications and was inspired by the poets that are known as the second generation New York poets, like Ted Berrigan and Ron Padgett and Joe Brainard and another ten, many of whom lived in this building. But I wasn’t part of that scene. I was too insecure and arrogant at the same time. I wasn’t looking to be accepted by an already existing group. In fact, Tom [Verlaine] and I would go over to open mic night and disrupt it. We’d get up and do stuff that was obnoxious and offensive.

MOLNAR: That’s not a million miles away from what T and Paul are doing in Godlike.

HELL: I’m not really proud of that, because I really loved those writers. So I knew everything about the process of being a high school dropout poet who printed magazines and wrote poems, but the characters are all made up. And I’m sure there are going to be some people or there have been people at St. Mark’s that were offended about the way I portrayed the poets that were part of the scene. But no, I was a big admirer of theirs, and I also kind of resented them because they had their own club and I wanted my own club.

MOLNAR: Have you ever felt like you’re in some kind of writing scene?

HELL: I was never in that kind of scene that they had back then where everybody came up at the same time with the same kind of poetic values. Even though they were street poets like me, they were all college-educated. I wasn’t, so I had to get everything I got from reading on my own. They had a kind of sophistication that I didn’t have, even though they were all drug heads and a good number of them were from working-class families. But they all went to Columbia and Princeton, et cetera. There’s been moments when I’ve felt the support and the comforts of community, but I just happened to be a guy who keeps to himself. It’s just not my nature. So even though I admire and envy people who have that, I haven’t ever really been part of a movement or anything. I mean, punk turned into a movement.

MOLNAR: Did it feel like that at the time? Like there were shared values and everything?

HELL: Well, it had offshoots. They had a whole set of standards that everybody had to adhere to. But even at CBGBs, there were certain things that people had in common. I mean, the way I felt about it was that the driving force was to write hard rock and roll that came out of real life again, instead of just being the usual comforting love songs and what all, about real experience which was kind of what it was like in the mid ’60s when I was a teenager. The music was where you got the news, and that wasn’t the case anymore. It just turned into this big industry of stadium tours and that part of it got lost. So that’s what I felt like we had in common—we were writing about actual experience again.

MOLNAR: When I moved to New York, Godlike felt like a roadmap to being a writer and living in the neighborhood, but it’s also very specific to poetry. But what brought you back to writing fiction, as opposed to memoir or poetry?

HELL: Well, I didn’t start writing fiction until I was in my 40s. It partly had to do with wanting to make a living. You’re never going to make a living from poetry, and I did not want to have a job. I loved poetry because it was the most concentrated form of pure writing, but I read plenty of novels and I liked the idea of trying my hand at it. So when I left music in the mid ‘80s, I had to figure out how to make a living. The first thing I thought was, “Okay, I left music because I was afraid to go back to music and pick up drugs again. And anyway, I didn’t really feel like I was suited for it. I hated the life on the road. And the only thing I liked about music was writing songs and recording in the studio.” So I thought, is there a possibility that maybe I could get work in movies? I’d been in like three or four obscure movies, but people had asked me to be in these movies. So I gave that a shot for about a year. I got an agent. I enrolled in an acting class where I broke my knuckles. [Laughs] I broke my hand by hitting the wall in acting class. And I pretty soon realized that wasn’t going to work out either. For one thing, you have to be comfortable having very personal rejections week after week after week. And I don’t respond well to rejection, so I started doing journalism because I knew I had a little bit of an advantage there because I had a certain reputation in music and there’s a lot of music magazines.

MOLNAR: And you’d already done some [magazine stories], right?

HELL: One or two small things, yeah. Just from being at CBGBs and meeting the magazine editors there. Opportunities came up, but that was all just random. The first major one was actually Legs McNeil’s idea, because he was doing a lot of writing for Spin at that time. And in 1986, it was the 100th anniversary of the publication of [The Adventures of] Huckleberry Finn. He had the idea of getting Spin to bankroll him and me rafting down the Mississippi, and we did. We just drifted down the Mississippi and camped by the side of the river each night for a week and then wrote a story about it. So I would be able to get gigs like that where I’d think of something I wanted to do. When there was a scandal in late ‘80s, when Boy George got busted for junk in London, that threw heroin way up into the news. And I’d been thinking a lot about heroin, what it was and how it works in society, so I got Spin to send me to London for a week. It wasn’t anything to do with Boy George except that he brought the thing into the news. It was me just going to London to feel out what was going on over there, how prevalent dope was and what the situation was legally. So anyway, it was working, the journalism thing, and I was figuring out how to write sentences that succeeded. So I started thinking, “Well, the next stage is to try a novel.” So that’s how Go Now came about.

MOLNAR: What was it like publishing Godlike, and also its afterlife? It’s not common to do an interview about a reissue.

HELL: Well, the original came out in 2005. I was working on it probably for five years. That’s usually how long it takes me to write a book. And I had a good agent, Betsy Lerner, who was Patti Smith and Jim Carroll’s agent. So then when I wrote this, Betsy tried to find a publisher and none of the big publishers were interested. So I can’t remember how Akashic [Books] arose, but the guy, Johnny Temple, he came out of a band. Anyway, he agreed to take it on. He liked it and wanted to publish it. After he’d accepted the book he said, “Oh, by the way, I have another imprint called Little House on the Bowery that is edited by Dennis Cooper, and I’ve shown him your book and he’d like to be the one who brings it out. Would that be okay with you?” And I was a huge admirer of Dennis. I think he’s the best novelist in America. So, hell yeah, sure, I would love to be edited by a writer who’s better than me. I didn’t expect that ever to happen. But he’s a very hands-off editor. He made like, three suggestions.

MOLNAR: What were some of the suggestions?

HELL: There was a comma. [Laughs] And something that I’d already thought through in a very early part of the book, where it says there’s a microphone in the corner of the bar where they’re holding poetry readings. I have it “leaning thinly,” and I knew that that was technically incorrect. How do you lean thinly? But I liked it. I thought it was effective. So Dennis queried that, but it’s not like he really had a problem with it. He just said, “You sure you want to say that? ” And I said, “Yeah, I do. ” And that was about the extent of it. Anyway, it got rave reviews from four or five intelligent people who reviewed it, but it’s a small press that doesn’t have any way to promote anything, and it’s a difficult book. I mean, I find it compelling. I find it keeps you reading, but it has its challenges.

MOLNAR: The first-person, third-person?

HELL: Well, there’s a lot of poetry in it. Who cares about poetry? And it’s deliberately offensive. I mean, it’s full of people doing stuff that’s obnoxious. But it just had the usual life of a small press book. It had its enthusiastic partisans and a much larger number of people who were completely unaware that it existed. Anyway, I was careful when I went with a small press with it. I wasn’t actively trying to find a publisher for any of those books, but in the last four or five years I’ve been thinking, “I’d like to get Godlike on the shelves again.” But I didn’t really have a plan. Then after I published What Just Happened, I started really feeling motivated to find somebody to bring out Godlike, thinking about who would be my fantasy, ideal, dream publisher for this book. And NYRB is the first thing that came to mind, because I got my college education from the New York Review of Books and that series that they do is probably the most interesting thing going on in publishing.

It must have been like six months after What Just Happened was published. Edwin [Frank, editorial director of the NYRB Classics series] said, “All right.” I wrote him describing what the book was and I gave him a link to one review of it by somebody I knew he knew. And I said, “Would you be interested in considering this? ” And he wrote me back saying that he’d been at my reading at n+1. He loved the reading and he said, “Send it to me right away.” That was a total dream come true. He’s really a saint of literature. What he’s doing is really admirable. So that was a real bit of good luck.

MOLNAR: Back to the book, I love the part about how T’s poem sources weren’t characters, but a pure version of a mood or insight. That’s something that gets at writing any kind of fiction too, beyond poetry. I don’t want to presume, but do you think of the characters–

HELL: Well, I do think that, in the past century or so—I mean nothing is really new—but there’s been a kind of flourishing of the idea that the poet’s eye in a poem doesn’t necessarily refer to the poet. The idea that identity is multifarious. I tell this story a lot, but when I was writing my autobiography, my mother and my sister would send me stuff they had in files or whatever, relics of my life that might help me in working on the book. My sister sent me a letter that I’d written to her the first year that I came to New York. I was on my own in New York and I wrote her this long letter about what things were like. And if I hadn’t known when I read that letter, I would have had no idea that it was me who wrote it. I did not recognize the person. And I think that’s what I’m getting at. That’s part of the reason why memory is so slippery—because you are actually a different person.

Ezra Pound wrote Personae. Whitman had “I contain multitudes.” It’s a thing that’s been in the air for almost 200 years now as a different kind of lens for looking at literature, but specifically poetry—that it’s not necessarily confessional or some kind of solid, permanent identity. It doesn’t have to be consistent. You can write a poem that seems to completely contradict everything about another poem that you’ve written, and they can both be good and both be valid. People’s identities are really fluid and multifarious. Just like whenever somebody murders somebody, all their neighbors say, “He was such a nice guy. He gave candies to the …” Or Nazis crying while they’re listening to Bach or whatever. I mean, people aren’t consistent. Oliver Sacks has this cool thing in there that he discovered as a young neurologist that not only are we totally subject to powers that we don’t control—in other words, free will is a fantasy—but we’re composed of components where there’s not a real person there. You think that somebody cruel can’t be somebody sensitive, but that’s not true. And for me, always from the beginning, I wanted to have multiple voices. I didn’t want to be restricted to one voice. I didn’t think that was true to life or a worthy objective for me to find my own voice. I just wanted to write well. It could be in anybody’s voice. I didn’t give a shit.

MOLNAR: How do you think that fits into the idea of the title? Because in the afterword, you’re recalling how Raymond Foye asks about Godlike as a title and you’re saying that T is “godlike” because he’s talking about how he’s true to how things are.

HELL: I mean, we’re always searching for how things are. That’s what I’m always searching for. To me, it’s the logical definition of god in the sense of “it’s how things are.” It’s what made you and everything else and what your fate is—it’s how things are. And the object is to try to do your best. It’s not something I’m prescribing for others. It’s just for me, to try to figure out what the fuck is going on in the hopes of being able to be comfortable in it, find harmony with it somehow, so that you’re not always uncomfortable and dissonant and have a little peace of mind.