lit

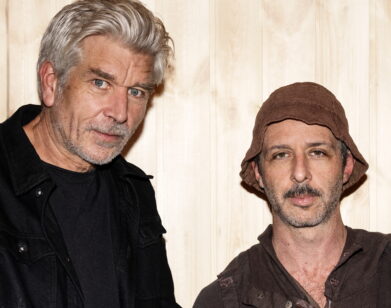

“I Couldn’t Have Written This 20 Years Ago”: Claire Messud, In Conversation With Joshua Cohen

Claire Messud’s sprawling new novel, This Strange Eventful History, is, as its title implies, more than just a novel. The layered, postcolonial saga draws upon Messud’s own family histories and records, including her grandfather’s unpublished memoir, to detail the diaspora of a French colonial family during the fallout of the Algerian Revolution. Messud’s work, in some ways, upends what we have come to see as a typical postcolonial narrative. She’s concerned with “the influence of the colonized on the colony,” she told the Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist Joshua Cohen. “People live in relation to one another, even with egregious power imbalances,” said Messud when the two spoke on Zoom earlier this month. Above all, there is a certain ease and effortlessness to Messud’s storytelling even as it spans decades, Cohen observed. When he asked how she approached writing her tour de force, Messud coyly responds, “It’s like learning the lines for the school play.” From the author’s room at a Hampton Inn, she and Cohen unpacked the genesis of This Strange Eventful History, her love of Camus, and what exactly it means to be “on the wrong side of history.”—JULIETTE JEFFERS

———

CLAIRE MESSUD: Are you home?

JOSHUA COHEN: I’m home. Where are you?

MESSUD: I’m in a Hampton Inn in Watertown. No bed bugs, though. There is a phone next to the bed, but I have not used it.

COHEN: I wouldn’t touch it if I were you.

MESSUD: Who knows what’s on the phone?

COHEN: Exactly. So I put together some questions for you. Does that work?

MESSUD: Lord knows I’m on the garrulous end, so I can fill up a lot of air.

COHEN: You sent me the book, and I especially like getting books before any of the publicity or marketing materials become auto-generated by artificial intelligence. But I’m reading the book description now to see how this thing, which is so epic and multi-vocal and multi-layered, is being pitched, as they say. And I see this line about a family born on the wrong side of history. I diagrammed the sentence and I said, “First of all, can you be born on the wrong side of history?” I think one can choose the wrong side of history, but being born on the wrong side of history, it bothers me. The little hairs prickle up in the back of my neck. And the idea that there is always a right and wrong side of history is antithetical to what this book is trying to bring out. So I think we’ll begin by slandering our publicity department.

MESSUD: Well, I think one of the things that’s quite complicated about trying to tell such a story now, in this particular moment, is that it goes against the idea that there’s only one version of everything, that understandings are eternal and universal, which they’re not. But I think to be born a white colonial at this moment, or to be talking about somebody who was born a white colonial, is a little bit like talking about somebody who was born German in the middle of the 20th century. I remember being struck probably in the early aughts, maybe 20 years ago, when all of a sudden Irène Némirovsky’s Suite française was published. And I was aware when I read that that I had not read any fiction about being German in the Second World War. Those were not stories that were told or were disseminated. I have a good friend who’s written a wonderful family memoir that has some fiction in it. Her name is Sylvia Brownrigg and her book is called The Whole Staggering Mystery. One of the things that she discovered as a young adult is that the grandfather she had never known was a British baronet who hung out with the white mischief crowd in Kenya and died of a drug overdose there in the ’30s.

COHEN: It’s like when a book writes itself.

MESSUD: Right, a fantastic story. But even in the ’90s, you could tell stories about that era and the colonial project was a sort of incidental backdrop to the lives of these people. But I think in this particular time, in this 21st century, there is a real awareness of the colonial histories and legacies and how terrible they were.

COHEN: Absolutely. I think there are so many factors that complicate that reading, though. One of them is the fact that they can no longer be in the place that they were born. It’s as if there are a series of trap doors. But one of the interesting things about [your book] is that, unlike so many of the family epics that we think of as classics, it’s not about the decline of a family. At least I didn’t read it that way. It complicates that narrative of a fall from some prelapsarian paradise that was colonialism and it turns it into something far more real and approaching, I think, the way that younger generations begin to reinvent the generations that came before them. I wanted to get into some of those relationships. You have the Gaston Lucien, this marriage, or at least it’s presented to the children in that way, and almost to the exclusion of loving their children to a degree.

MESSUD: Absolutely, yes.

COHEN: I didn’t want to ask that question of, “So how are your parents?” But I did want to know to what degree we’re supposed to read this marriage in the way that the children experience it?

MESSUD: I happened to grow up in a household where my parents quarreled a good bit. I always thought, “Oh, how terrible it is to grow up with parents who don’t get along.” And then I stopped to think about it and looked around at the sort of myth-making that went on in an earlier generation, certainly among my antecedents, and it became clear that having the myth of an ideal marriage was in fact a burden much worse. I sometimes think this about religion; that if you have religion to kick against, then you grow up thinking, “If there wasn’t any bloody religion around my house, things would be so much better.” But in fact, you’d be kicking differently against something else. Can I just say, the characters in the novel are fictional, but there are things drawn from family histories and records and so on. And one of the things that is just unbelievable to me is the number of times god or Jesus, but chiefly god, is invoked in the correspondence as though he was literally in bed with them. There’s a telegram that says, “Safely arrived in Casablanca, we must praise and thank him. He will keep us safe.” And I’m thinking, “Every letter of a telegram costs money…”

COHEN: They don’t give you god for free.

MESSUD: No. So for me, this is, among many other things, a book in part about stories and the stories we tell ourselves and how that shapes how we see our lives and how we see the world. It has to be said that the types of people on whom Gaston Lucien is sort of based, they grasped and held fast to fixed beliefs that gave them positive narratives that could sort of carry them through fairly rough times.

COHEN: And which then becomes the text that their children have to decipher. So much of the sibling relationship between Francoise and Denise comes through in this parsing of what their parentage was and what sort of model it provided for their own romantic lives, familial lives, political lives, and so on. And that brings us to my question about this book: how much of this background did you know or had you been able to imagine before writing it, and how much of this is osmotic, and how much of this is research?

MESSUD: It’s a really good question, and the answer is unclear even to me. There are emotional elements, and the valence of things was absorbed by osmosis. I would say there was lots of practical stuff I had to research. There were also lots of family things I didn’t know. But it’s worth saying that from the generation just above mine, I knew almost nothing. But for my sister and me, in his retirement, my grandfather hand-wrote a memoir, which is quite long and covers the years 1928 to 1946. But it fills in a whole lot of context and history. I was aware of that document, but I did not read it until 2017. I know that my grandfather had some sort of condensed version typed up and gave it to my father, who never read it and did not want to read it. So just knowing that little fact, I then understand by osmosis that, say, my father’s choices—as an expatriate living in Anglophone countries, marrying an Anglophone Canadian, raising his children in English as protestants—were not incidental.

COHEN: To my mind, the primary paths of exile are dialectically opposed, right? You have the people who leave or are forced to leave or some combination of the two, and they preserve within themselves, as if an amber, a version of their past that becomes this portable orthodoxy. I think that we see this in a lot of the ethnic neighborhoods in America, where Little Italy is Italy times a thousand. And then the other path is this path where, once you are uprooted, you are free to go to North America and to raise your kids as Protestants and completely change. I think it’s the former that we’re most familiar with, and that is responsible for, in my mind, a lot of bad politics. This idea of, “We have to make ourselves great again.” What your novel illustrates really well is a sense of being untethered and lost, and I wonder, when it comes to the Amherst scenes in the book, what you were feeling in terms of the correspondence between a fidelity to the character and a fidelity to showing a certain trajectory of family?

MESSUD: I guess I would say that those don’t seem incompatible to me. I think there’s the question of how much you can walk away from your history and how much it follows you. So I do think of that post-war moment, after the horrors of the Second World War, when many people thought, “Let’s just put that behind us, close the door, and begin again.” I think of Jewish friends of mine whose parents were Holocaust survivors who never spoke of it. Thinking of the Francois character, there’s the thrill of being something new in America, or freedom and discovery.

COHEN: Today, we believe in an exaggerated version of this, in almost Lamarckian trauma inheritance, and the idea that traumas of the previous generations somehow express themselves in our bodies.

MESSUD: Right, epigenetic.

COHEN: The book is very rich with a lot of description, or food and furniture especially, and a lot of the sensuality of the descriptions really reminded me of Lawrence Durrell. And certainly, the canvas of the novel brings me back to Proust. But I wanted to speak about the literature of colonialism, especially the literature of North Africa, whether it’s Algeria or, in Durrell’s case, Egypt. What is your relationship with that writing, if any?

MESSUD: That’s such a good question because, of course, those are writers who were very much present for me when I was young and becoming a writer. I don’t know how much they still have a presence. Jane Bowles was very important to me. Paul Bowles was important to me. Camus was important to me. But the book that I love the most is the unfinished Le Premier Homme [by Camus]. When I was a kid, we would go to my grandparents and we would go to lunch at Edith Wharton’s house in Yale. It was a restaurant then, and we loved it because it had a big garden, so we were allowed to run around in the garden while the parents sat and smoked at the table.

COHEN: It’s funny because I thought the whole thing about Edith Wharton was that she never ate?

MESSUD: Did she never eat? I know she spent a lot of time in bed. Anyway, my parents were both big readers. My mother loved to read all of those lady travelers who would go up the Nile. That was just sort of the background music of my childhood.

COHEN: I mentioned earlier that I love the furniture and food descriptions. But there are ways in which certain descriptions and certain passages in this book are synecdoches for, if you’ll forgive me, your mind, and for the multiplicity and the everywhere-at-once nature of this book. There’s this one description of a scene where there are Chinese rugs and Persian rugs and there’s a British House & Garden magazine, and then there’s a Baudelaire on the shelf, which causes her to remember a line from it. On one hand, this could be read as the stuffed parlor of the empire. But it also is the intellectual legacy of an empire. Even when these empires collapse, the cross-pollination continues. We talk a lot about the influence of the colonizer on the colonized. But what I think this book magically does is the opposite or reciprocal thing, which is the influence of the colonized on the colony because of what this family brings with them. I was kind of interested in whether you think about that relationship as fundamentally one of reciprocity.

MESSUD: I feel that’s several questions. It’s funny, I certainly do feel that it’s inevitably a relationship of reciprocity. People live in relation to one another, even with egregious power imbalances. They’re in conversation with one another and their cultures are in conversation with one another. One of the many lessons of my French family, which is very concerned with getting things right and being correct, was do not talk about things you know nothing about. But I can certainly say that in the small corner of the world that I came to know through my family, that legacy had very different manifestations. For my grandfather, it was both emotional and human and also scholarly. For my father, it was transmuted into scholarly knowledge beyond which there was no emotional register. And for my aunt, it was pure emotion.

COHEN: Well, treason I took us in this direction was that I was reading the book when I was coming back from Europe and the rise of the far-right across Europe troubles me.

MESSUD: Me too.

COHEN: One of the things that I find very interesting about it is the way in which it stages a civilizational battle with regard to people coming to these supposedly democratic and open countries in pursuit of a better life, whether they’re fleeing war, whether they’re fleeing famine, or climate change, and so on and so forth. And there are continual appeals to this classic European concept of ethnic purity. Reading your book is an amazing experience of an almost Sub rosa rejoinder to this, showing how this family that felt it was more French than French actually sort of wasn’t. I don’t even know even that there’s much of a question there, except that what was very fascinating to me was how, at the book’s fulcrum, you’re able to draw lines to a contemporary political situation that has brought the problems of colonialism home.

MESSUD: My family name is Maltese, and the fictional name I gave the characters is also Maltese. My grandfather’s paternal side was Maltese, which was not in the hierarchy of Frenchness. That was considered sort of barely on the side of French over indigenous, so barely white.

COHEN: Where was it next to Corsican?

MESSUD: It was below Corsican. So if you think French, Italian, Spanish, Corsican’s in there, Maltese, and then Algerian. So one of the things that’s quite interesting, not just in terms of my family history, is that my grandfather had a brother who became a school teacher, a communist. My grandfather was Catholic and did very well in school and went to Polytechnic and joined the Navy, so that was one route. And his brother went the opposite route and became a sort of communist school teacher who went out to teach in rural communities. And interestingly, his politics became ultra-conservative later in life, whereas the Navy guy stayed a center-right.

COHEN: And I am sure once you get into an institution like the Navy, it just becomes more and more calcified, right?

MESSUD: Absolutely. I think it’s like joining a club.

COHEN: The other thing I wanted to get to, and I think this is a hard and abstract kind of question, is where you feel this book fits in with your other books. To maybe sharpen the question slightly, certain books have the feeling that they have been gestating for a very long time. You’ll tell me if I’m wrong, but I can hear portions of this book in things that you’ve written before, almost as if it’s the undertone to some of them. Do you see those connections?

MESSUD: Thematically, there’s certainly [overlap] with earlier novels, The Last Life in particular. The sort of boilerplate answer is that I’ve been preparing all my life to write it. But it isn’t something I could have written 20 years ago for any number of reasons, formal and technical reasons and emotional, human reasons. But I also feel that it is, on every level, connected to the other things that I’ve done.

COHEN: The Last Life, which I love, has the Camus shadow though all over it. And something I very much admire about this book, as someone who has horrible trouble with plots and completely mistrusts them most of the time, is that you are not constrained by this sort of limited point of view to then resolve action. You found a way to split these plots into multiple plots that overlap and interact and their patterns sort of reflect one another and recur over generations. And I guess my question is, did it feel good? I feels like there’s some freedom to it.

MESSUD: That’s one of the reasons why I couldn’t have written this book 20 years ago. It has its form and its form makes sense to me. But I’d also say that the form that it has is the form of life. As several people have observed, there are quite a few deaths. Goodness, there are quite a few deaths in this book.

COHEN: I am sure you suffer from the same disease that I do, where you end up reading things as a novelist and looking for things that you would’ve done differently. But this book has a freedom and fluency where it’s like, “Fuck it, I’m going to tell you what happened between 1939 and 1943 in this paragraph and it’s just going to flow at you like water.” I always think of that [Maxim] Gorky line about Tolstoy, that reading Tolstoy is like drinking a large glass of cool water. And I wonder, purely novelistically and for purely selfish reasons, about your desire to tell and tell and tell and tell and really only dramatize and have a scene when you want to.

MESSUD: Well, I rather love it that you put it like that, but I don’t know that I can articulate how that happened.

COHEN: You were never afraid that you were telling too much?

MESSUD: In five minutes, I’m going to have to dash because I think somebody’s going to call me on the phone, just so you know.

COHEN: This is how you get out of telling me your secret. It’s okay, we don’t need to share trade secrets. But I have to say that that element was the most impressive to me because it felt, simultaneously, the most classic and modern.

MESSUD: Well, thank you. I don’t have an answer though. Who knows? It’s like learning the lines for the school play.