MEMOIR

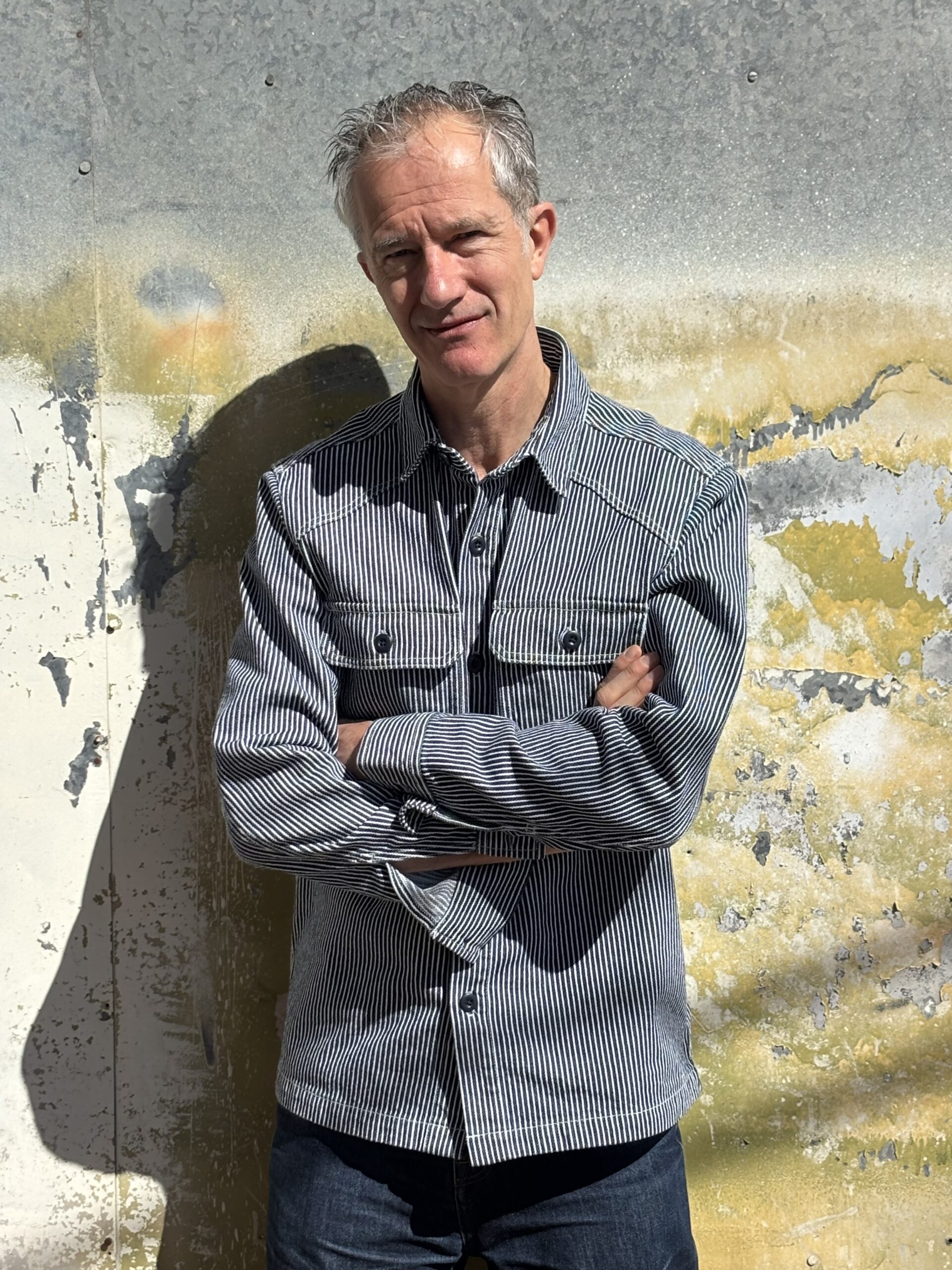

“Giving Up Is a Great Source of Happiness”: 30 Minutes With Author Geoff Dyer

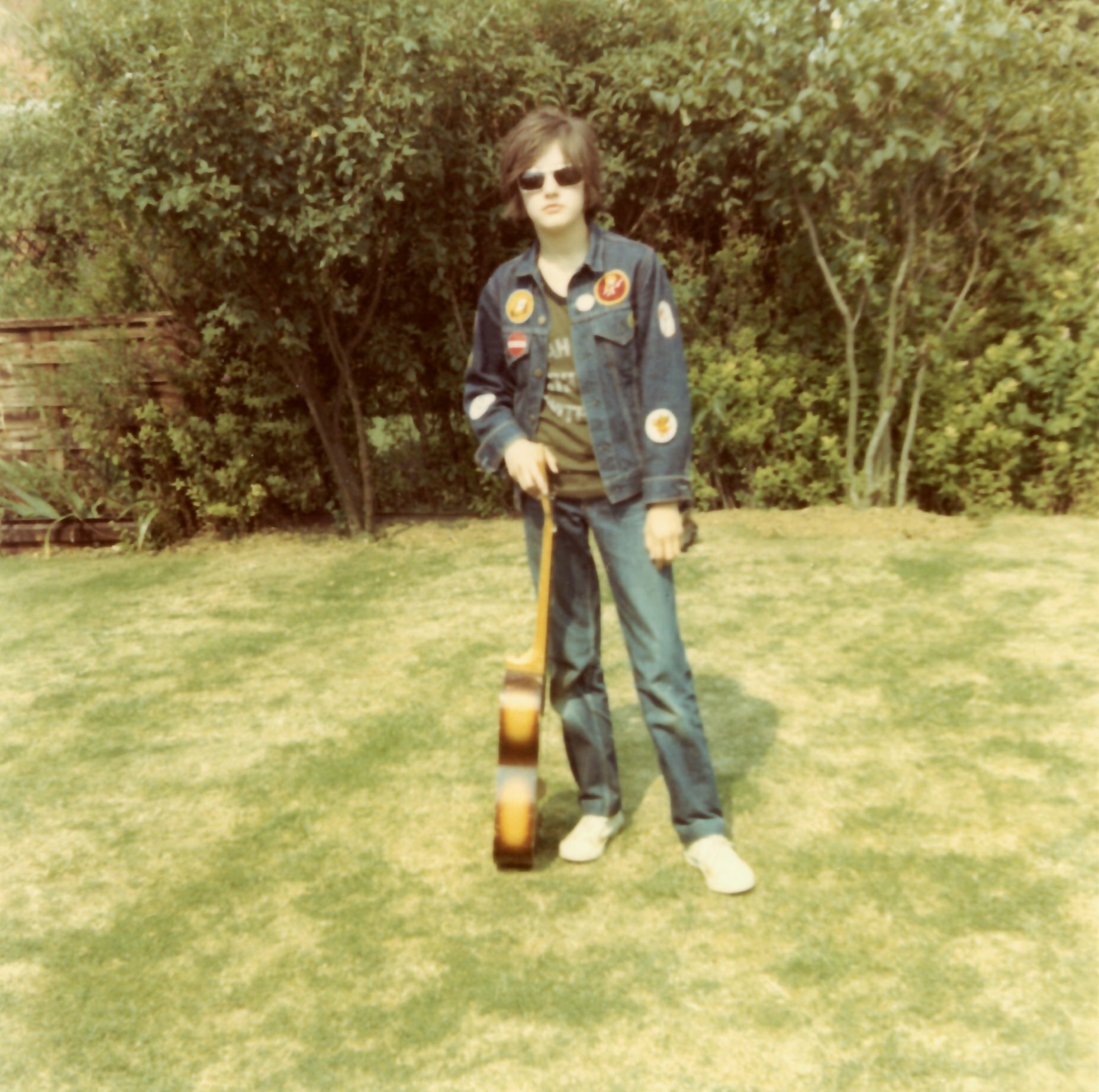

For the last 40 or so years, the author Geoff Dyer has become one of the most distinctive voices in contemporary literature by applying his caustic wit and boundless curiosity to a number of sundry topics, from the works of Adrei Tarkovsky and John Berger to whole art forms like jazz and photography. Throughout, Dyer nosedives into new domains and disciplines like a paratrooper; under his stewardship, the very task of exegesis becomes an exercise in literary tourism. If you ever wondered how Dyer got this way, the 67-year-old writer’s new memoir, Homework, is a good start. Here, he takes us back to Cheltenham where, as the son of a sheet-metal worker and a school cafeteria lady, Dyer was “home-schooled in notions of acceptance I later found entirely unacceptable.” Somewhat surprisingly for a stylist who wrote an entire book about his exasperating attempts to write a biography of D.H. Lawrence, Dyer shepherds us through his adolescence in fairly straightforward fashion, notating his memories and misadventures—getting a Red Feather racing bike; being punched in the face; passing his 11-plus exams to get into grammar school—against the backdrop of post-war England. Along the way, a charming portrait of filial piety and working-class pride emerges. “I’d be very delighted if an American audience can see that,” he told me earlier this month. “Although there is class in America, it just doesn’t exist in this all-defining way that it does in Britain.” Just after the book’s release, Dyer joined us to talk about turning inward, conjuring his childhood, and giving up on tennis.

———

JAKE NEVINS: Hey there, Geoff.

GEOFF DYER: Hi. Can you hear and see me?

NEVINS: I can hear you and see you perfectly. How are you doing?

DYER: Great, thank you. Good timing, all very punctual.

NEVINS: Well, the timing worked out quite nicely, actually, because we’re both tennis fans and we’d be remiss to not talk about Sunday’s final.

DYER: Oh, I’m so sorry to disappoint you, I’ve completely lost interest in tennis. I loved Roger so much that it’s like I’m some widower who loved his wife so much that they would never marry again. It just sort of faded away. And then that coincided with me stopping playing as well, because I was deteriorating, wasn’t enjoying it so much, and every time I played it just left me feeling so wrung out afterwards for days on end. Giving up on things is really a great source of happiness in life.

NEVINS: [Laughs] This is true.

DYER: Having said all of that, I gather that it was a really amazing match. The level was insane, as [Carlos] Alcaraz said, but I really can’t muster up that much enthusiasm when it’s both players with a two-handed backhand. And also, I was conscious of the incredible amount of time I was saving by not watching it. I mean, that was a particularly long match. And if I could find on the internet an hour’s worth of highlights, that would be good. As it is, I can only find 11 minutes, which is not adequate. You watched it?

NEVINS: Yeah, I did watch it, all five-and-a-half hours. I’ll snoop around for a nice hourlong super cut for you. But we’re here to talk about Homework, which I so enjoyed reading, as I have all of your books. I wanted to start by asking you about what I hope I’ve accurately pinpointed as a bit of a shift in your work as of late. In your early books, you often take up particular subjects or contemporary phenomena. And in these last two books, The Last Days of Roger Federer and Homework, you’ve turned inward. Which is not to say that you didn’t write about yourself previously, but now you’re writing about beginnings and endings, and you’re your own subject, if you will. Was that a conscious decision, or is that simply where you’ve found your attention drifting?

DYER: I guess the last book, the Federer book, I was applying myself to the works of a lot of other people. And I mean, some of the interest of that book is in what I say about those people. And that proceeds in parallel with, of course, my own entering the late middle-age twilight phase of my life, I suppose. If you look at sort of military history, which I read a lot of, sometimes you’d be pretty hard-pressed on a sort of blindfold test to work out from a passage whether it was Max Hastings or Antony Beevor or whatever. And that’s great. But then there’s this other kind of non-fiction book, as exemplified by people I like a great deal—Annie Dillard, let’s say, or Rebecca West—where as much as the ostensible subject matter, it’s the consciousness of the author that the book is so saturated with that it means that’s partly what the book’s about. So I think that Federer book fell into that kind of category. It was about that particular subject, but really it was very obviously a book by this particular person, me. And even the stylistic things aren’t just stylistic things, they’re part of a whole apprehension of the world. So yeah, I don’t feel there’s a trajectory to be traced here. I think it just happens that that’s what’s going on at the moment. I’m more present in some of the older books than I am in others.

NEVINS: The book takes us right up to Oxford, and the narration is mostly chronological. Was it always the plan to tell this story in a pretty linear, straightforward manner?

DYER: Well, I had a very novel, unusual structural sort of idea for it because I’d contributed to this box of maps, which I mentioned in the note at the end. And I was going to organize this book along those lines. That is to say, it was going to be organized spatially rather than temporarily, geographically rather than through time. So that was the idea, but before I could implement that, I had to have a certain amount of material. So I was just writing stuff, and that was fine—a scene here, a scene there. And then, as I began to think at the point where I normally do about structure, an organizing principle emerges. And at that very point, I was noticing that this idea I had for a structure, far from enabling me to fulfill what I wanted to do, was really serving as a kind of impediment. And then it became like a brick wall. It became obvious that it was impossible to arrange the book like this. So it was only at that point, after much trial and error, that I kind of had to call “uncle” and submit to the fact that the best way to organize this book was chronologically. So I did at least arrive at this conventional form by a process of experimentation. In other words, the finished form was arrived at in the same way that the finished form has been arrived at with the other books. But I tried my best to make it unusual.

NEVINS: And did you always know that the passing of the exam would provide a kind of fulcrum for the narrative?

DYER: Exactly. The book falls into two halves. The 11 plus ends one half, and then that propels me into the second half, and then we end with those two great triumphs of A-Levels and Oxbridge, and then there’s a little afterword. But yeah, that was another reason why inevitably the book ended up being chronologically arranged, because of those determining exams.

NEVINS: Well, let’s turn to the content itself. I was struck by the incredible level of detail with which you render your childhood: the thread of gristle connecting two blocks of meat at your school lunches, or the foul smell in the boy’s showers after football. Did you have any diaries from that time to refer to?

DYER: On the one hand, it was no different to any other kind of writing, where it’s always about the level of detail you can come up with. To take a really classic example, let’s suppose man falls in love with a woman. That’s a universal theme. So the first word that comes to your mind if you are describing this happening is, “She was beautiful.” Well, actually, I don’t know how many people there are in the world, but half of them are women, and quite a number of them are beautiful. So that word really doesn’t have any specificity to it. So you have to keep narrowing it down.

NEVINS: Of course.

DYER: I always come back to Edith Wharton and The Age of Innocence, where there’s a line like, “All the things that made her her…” Because you’re not falling in love with 20 billion people or whatever it is. If she’s wearing a dress, well, we need to see the dress; if she’s in a room, we need to see the room. So it’s always detail that substantiates what’s going on and puts the reader in that room. In this instance, I was guided by incidents and scenes that I happened to remember for no particular reason. The very fact that they’d stuck in my mind was enough to give them a legitimacy, even though it remains a mystery to me even now why these moments lodged in my mind. And if they were in my mind, that means they could be seen. And then in addition to that, when I got into writing about the age of 17 or 18, of course I had nothing to write about except my family life, so I wrote about these scenes. And then miraculously, I kept these rubbish pages, and although they were, of course, rubbish, they were packed with detail. So I was able to extract the detail from all this dross. And not only that, but in some compensatory way, it meant that I was writing about scenes that I hadn’t written about before. Then, in some weird process that I don’t quite understand, it meant that the intensity of recollection had to correspondingly come up to those other scenes where I’d had this reservoir of previous documentation to draw on.

NEVINS: Selfishly, I’m wondering what you can recall from those early diaries—a turn of phrase of some stereotypically 17-year-old sentiment?

DYER: Oh, there was nothing remarkable about it. It wasn’t at all like that amazing novel that the young kid is writing in Don DeLillo’s The Names that constitutes the last section of that book, which has a quality of genius to it. No, this was just inept. But it was like when they make some archaeological discovery, and there it is, perfectly preserved, the ring or whatever. Everything else was rotten and smelled bad, but there were a lot of these images that, while imperfectly expressed, were perfectly preserved.

NEVINS: And good for your purposes. This is a good segue, actually, because I wanted to ask you about something you said in The Paris Review in 2012, which was that any reasonable assessment of what you are doing as a writer would not accept the segregation of nonfiction and fiction. I’m wondering what sort of freedoms that hybrid conception of genre afforded you in the writing of this particular book?

DYER: Oh, that’s a great question. A lot of the nonfiction I wrote, it really didn’t matter whether it was… It wasn’t a court deposition, I wasn’t Stormy Daniels testifying, so it really didn’t make any difference and I felt very free to embellish because people were going to it as—and and I was offering it as—a literary experience. But I think with memoir, you do have a kind of contractual obligation with the reader to be as faithful to what happened as possible, or faithful to your memories of what happened. But because I didn’t come from a family of writers, I was given a certain amount of freedom. Even when I’d signed that contract, that covenant, I still had a certain amount of leeway because there wasn’t this great stash of documentation against which something I said could be checked. But I was always trying to be faithful to what happened. And then there’s those various bits in the book where I think maybe I’ve got something a bit wrong. And I say, surely my memory has some sort of trumping power. If I believe this is what happened, then it sort of did. But my impulse was always to be faithful to the historical truth, even though on many occasions I’m the only witness to what happened.

NEVINS: Have you noticed a difference in the reception to the book between English and American readers?

DYER: To use the old Zhou Enlai line about the French Revolution, “It’s too soon to tell.” But I think I can already anticipate what the difference would be because Alex Star, my editor, felt it might be a good idea if we included an introduction to sort of really bring out that this book is about is class. And I resisted that partly because I don’t really like books with introductions where you tell the reader what you’re going to do. I’d much prefer the reader discover the kind of experience they’re in for. And I think in Britain, it’s obvious to everyone, especially but not exclusively to people of my age, the way that this defining English thing of class, this preoccupation with class, saturates every line and everything in the book. I’d be very delighted if an American audience can see that because, although there is class in America, it just doesn’t exist in this all-defining way that it does in Britain.

NEVINS: Well, I thought that was eminently clear. There’s one line in particular that comes to mind, when your mother refers to certain things as “common” and others as “nasty.” You write, “The important thing is the need for some kind of hierarchy, even if it exists only linguistically within a shared tier of social formation.” I thought that was a wonderful observation.

DYER: The gradations of the class thing in Britain, it’s almost like the Hindu caste system. I can’t remember the exact line now, but [George] Orwell talks about upper-lower-middle-upper class, or whatever it was. There’s always scope for some sort of snobbery, and it’s about that experience of growing up unconscious of this notion of class, really.

NEVINS: Has living in Los Angeles brought you any new perspectives on these dynamics? A few months ago, you wrote powerfully about the wildfires, and this past week there’s been even more upheaval in L.A., with the President deploying the National Guard against demonstrators.

DYER: Oh, my god. Well, yeah, I can really feel the rage and the fear of the people there, because, of course, it’s a cliche, but so much of the hard work is done by immigrants from Latin America. When I was there until just about three weeks ago, there was a real sense of fear. I don’t have anything interesting to say because, like most people, every morning I wake up and we just discuss it and all we say is that it’s just unbelievable what’s happening.

NEVINS: Everything is unprecedented these days.

DYER: It really is. But it’s funny, because in some ways, L.A. is a rather boring place to live until something catastrophic happens. And then weirdly, either because of meteorology or geography or politics, quite often something catastrophic is regularly cropping up.

NEVINS: Well, Geoff, thanks for your time and this wonderful memoir. I enjoyed talking to you.

DYER: You too, Jake. This was a real pleasure.