PRIDE

Glenn Belverio on Genderfuck, Street Activism, and the Tyranny of Modern Drag

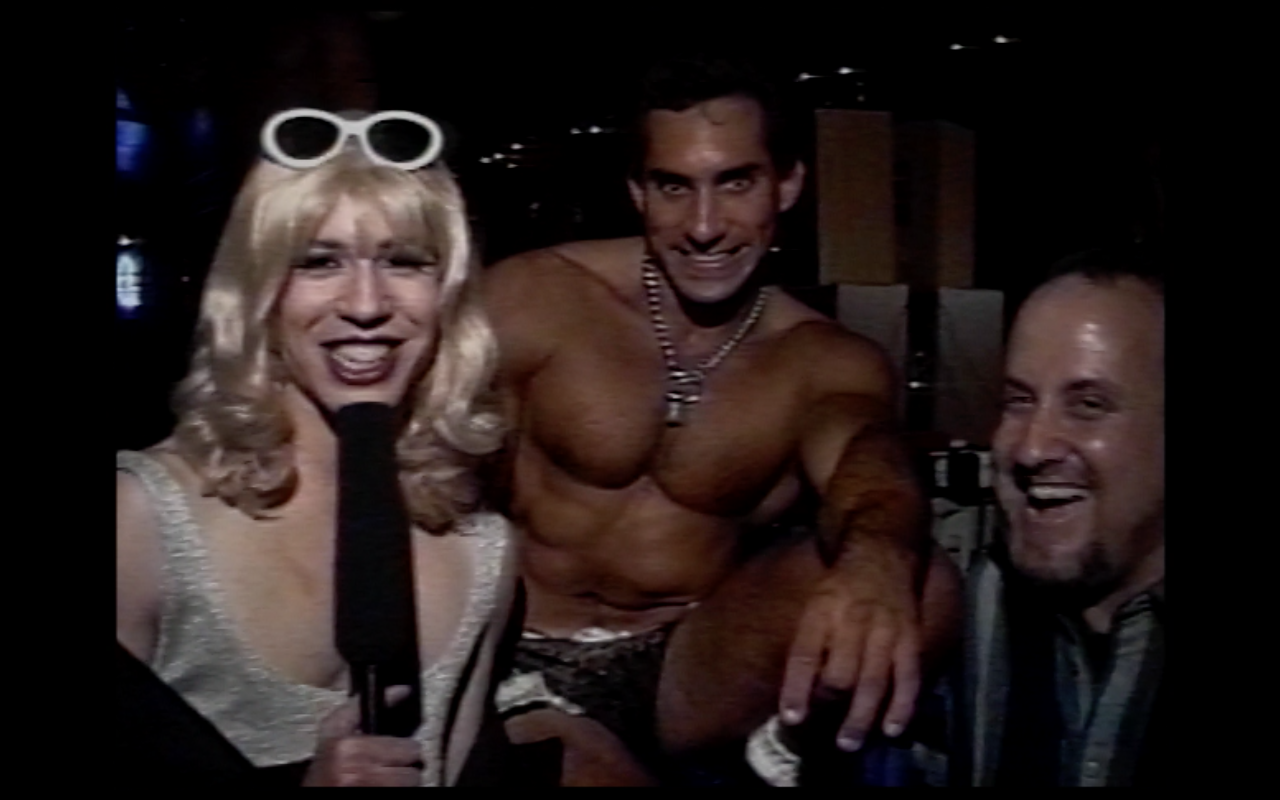

Production still from Glennda and Camille Do Fashion Avenue (1995). Photo courtesy of Giovanni di Mola.

My talk earlier this month with Glenn Belverio, the writer, filmmaker, and drag intellectual (though he’s not sold on that label) turned out to be a reexamination of bohemian New York life in the 1990s. But as much as our exchange touched on the past, the topics discussed proved remarkably current. If most drag is about the experimentation with expression of overtly feminine tropes, Belverio’s version—rooted in fun, but also activism and genuine curiosity about the human condition–has always charted a slightly different path. Over the years, interest in the 59-year-old’s practice has been sustained: cultural institutions like the Video Data Bank, where his video archives of his cult Manhattan Public Access shows—Glennda and Friends and The Brenda and Glennda Show—are available to screen. Belverio is also often invited to speak about the intersection of gay politics with the mainstream. In October, his 1996 video One Man Ladies, an episode from The Glennda and Friends Show, will be featured in the exhibition Vaginal Davis: Magnificent Product, opening at MoMA PS1. In a wide-ranging discussion below, which took place as Pride Month got into full swing, he and I discussed divisions amongst allies, the complexity of sex and expression, and if the fight for equality was ever really won.

———

CHRISTOPHER BLACKMON: How did Glennda Orgasm start? What was going on in your life that provided fertile soil for her to come about?

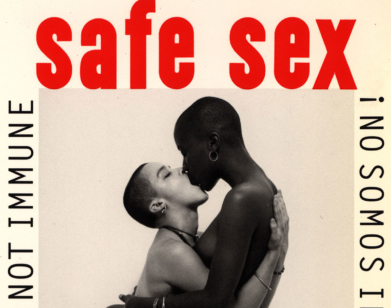

GLENN BELVERIO: I’m sort of famous because of the work that I did with Camille Paglia, and then the more satirical stuff I did with Bruce LaBruce. It started out as this very earnest tool for activism using camp humor to bring issues around queer visibility and AIDS and abortion rights to a public access audience. Then, as the show evolved over the years and I started working with guest co-hosts, the tone changed and it became a little critical of mainstream gay politics. A lot of the stuff I did with Bruce LaBruce was really about taking the piss out of things.

BLACKMON: What instigated that change from something very activist to something a little bit more satirical?

BELVERIO: Well, the show started out as a result of my activism in ACT UP, which I joined in 1988. I met Duncan Elliott in 1989 at Wigstock while I was working on this public access show called Talk to Go. It was very much about the downtown scene. We were interviewing people like Lypsinka and Hapi Phace. Then, we decided to do a filming at Wigstock, and the guy who was producing this show, Rob, was like, “Oh, I know this guy Duncan Elliott, who just started doing this drag character, Brenda Sexual.” I didn’t have a drag persona yet, but I had borrowed this really ratty wig from Hapi Phace, who was a famous drag performer from the Pyramid Club and was one of my drag godmothers. We interviewed all these people at Wigstock and in the middle of the event, some teenagers came into Tompkins Square Park and just started attacking drag queens and bashing them with hockey sticks. Some of [the attacked] were comrades from ACT UP that I knew—there were a lot of ACT UP people there that day in drag just trying to enjoy the day, this day of queer love and joy. And it was shocking that people felt that they could come into this queer space and just commit these acts of violence. There were people from ACT UP that wanted to go on stage and announce what was happening so that we could rally and defend ourselves against the gay bashers. And she hates when I tell this story, but Lady Bunny wouldn’t let them on stage.

BLACKMON: Do you know the reason why?

BELVERIO: The concept of Wigstock was that there would be no political platforms, so it was just a day of performance and drag and camp. But there was a schism in the downtown scene of people that didn’t like ACT UP activists. They thought we were troublemakers. And then, of course, there were activists who moved through both worlds like I did. I went to the Pyramid Club and I went to ACT UP meetings every week.

BLACKMON: It seems those in ACT UP were, for lack of a better term, the professional gays. They had day jobs, and then the downtown scene were the kooky artists. Is that not correct?

BELVERIO: Well, ACT UP was a real mix of people. And now that you mention it, I definitely was not a professional gay when I joined ACT UP. I did have a day job, but it was a very working-class job. I worked in the garment district in a sweatshop cutting fabric. It was my first job in New York, but I had a very bohemian life, and I was going to The World on Tuesday nights and then being out till 4 AM and then dragging myself to this sweatshop in the garment district. I think we had to be at work at this ungodly hour of 8:30 AM. And when you were 21, it was easy to survive on three hours of sleep.

BLACKMON: In the Black community, the same schism exists within the Black Civil Rights movement. They call it “respectability politics”—the idea that one may not be going about it in the right or clean or respectable way. Instead of getting a meeting with your Senator, you’re busting through the doors of a department store.

BELVERIO: Totally, and we were causing trouble. And maybe we were creating negative perceptions of the gay community because we were blocking traffic. Even though people were dropping like flies from AIDS, [a lot of people] didn’t want the party to end, so they were kind of ignoring it. There’s this story that I always remember. I was working on this gay fanzine called Pansy Beat with Michael Economy, who is this artist who worked with Deee-Lite. And they let me be the political contributor. We would go around to places to try to drum up advertising, and he introduced me to Patricia Field and said, “This is Glenn. He’s in ACT UP. He’s our political contributor.” And of course, Pat was smoking a cigarette, and she goes sarcastically, “So you’re political, that’s nice.” So there was this kind of hostility, and I think a lot of these people changed their tune when they saw how productive our tactics were.

BLACKMON: You woke up society.

BELVERIO: Oh, so after the bashing at Wigstock, the producer of the show Talk to Go said, “I don’t want to use any of the footage.” He didn’t want the show to be political, even though he was in ACT UP. He wanted this public access show to be just fun. And then we went over to the police precinct to demand that the police do something about the gay bashing. That’s when we decided to launch The Brenda and Glennda Show, that was in the summer of 1990, and we wanted to do something that was fun and campy and funny, but use it as a Trojan horse to bring political issues to people that were watching public access television. We filmed the first episode on the 9th Street crosstown bus, and it was all about bringing drag and queer visibility into the public. It was really raw. We didn’t have a handheld microphone. We were interviewing people in the back of this noisy bus. You could hear the bus engine, and we were kind of yelling into the camera, but the whole point was about being out and outrageous in public and promoting queer visibility because, in 1990, it wasn’t easy to be out and you didn’t see any drag queens. We wanted to bring drag out of the nightclubs and into the streets.

BLACKMON: In those early days, what was the reaction to you doing live interviews? New York is a very progressive place, but it also has a rigid, conservative side.

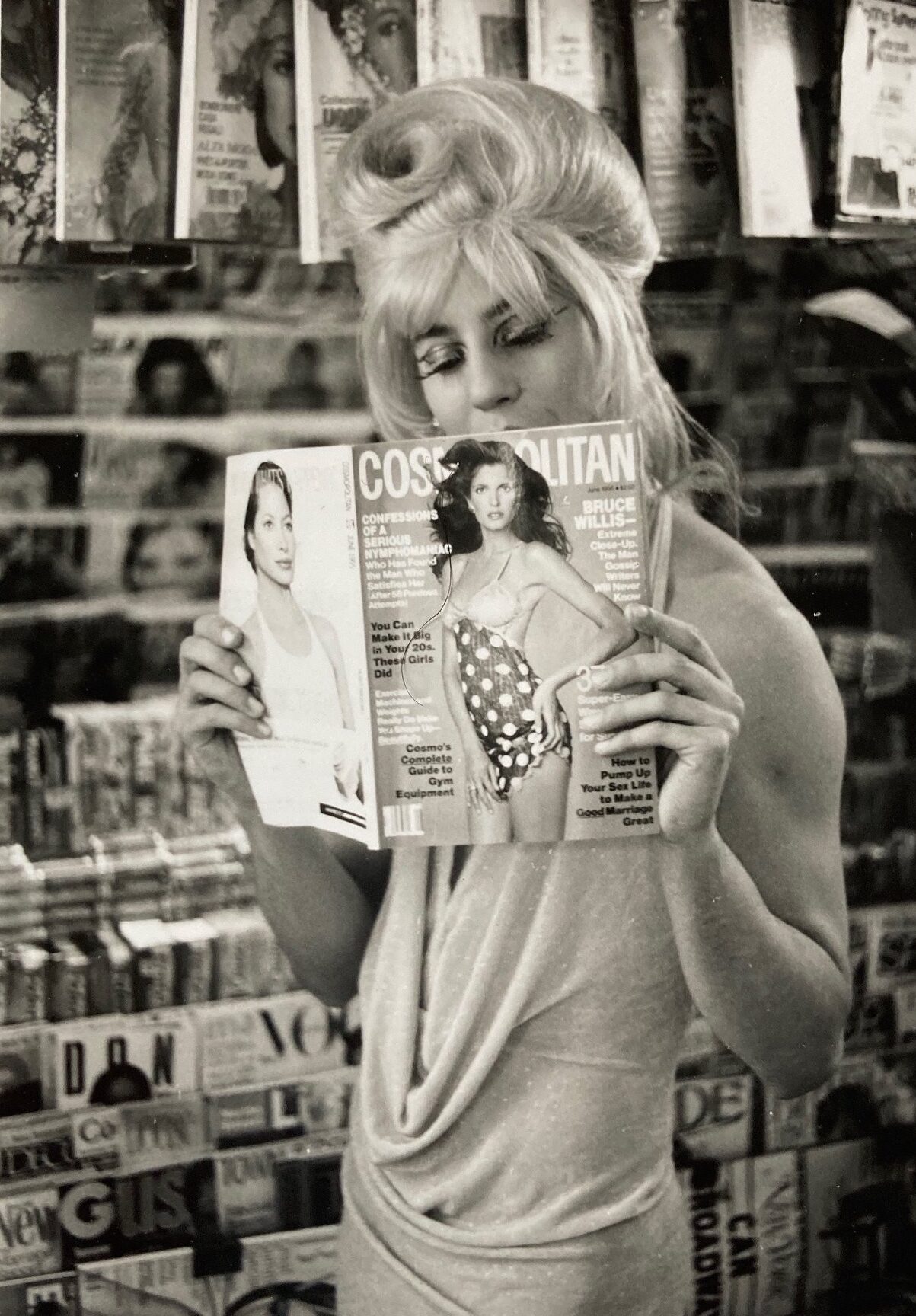

Production still from Glennda and Camille Do Downtown (1993) featuring Brian Roach, Stevin Azo Michels, Camille Paglia, Glennda Orgasm, and Rennard Snowden. Photo courtesy of Isavel Stillwolf.

BELVERIO: The time that we really experienced violence was when people spat at us and called us fags and were calling us the AIDS parade when we went to Atlantic City to Donald Trump’s Taj Mahal Casino in 1991. Someone threw a brick at one of the drag queens, Lindira. Luckily, I don’t think it hit her. It really felt like, “Uh-oh, we’re out of New York, we’re out of our liberal bubble, we’re in the wild.” When we did the bus ride, a little old lady yelled at us, a homophobic old lady. She wasn’t happy with what we were doing, but I think maybe the cameras created a little bit of a buffer. But when there weren’t cameras and we were on the street in drag, yes, I do remember people yelling at us.

BLACKMON: And that’s sad, too, because you think of New York as a more accepting place.

BELVERIO: Well, I think it’s come back because of the hatred that’s been riled up by the Trump administration. Now it’s very acceptable to hate drag queens and trans people and gay people again. They’ve been given permission, they’ve been encouraged.

BLACKMON: Camille Paglia is sort of your intellectual partner and co-star. In an upcoming essay you’ve written for The Queer Majority, she has a poignant quote. “When ACT UP behaves well, they’re fabulous.” But when they’re doing things that she doesn’t agree with, “that’s 30 more years of gay bashing.” Do you think that you guys were correct in how you went about things?

BELVERIO: Well, what she said was, “When they do things like invade a church and throw the communion host down on the ground, that’s another 30 years of gay bashing.” I don’t know, that feels a little exaggerated, but that was one of the big debates within ACT UP when we were planning that action. Do we just protest outside of St. Patrick’s? Or do we invade the church and disrupt the service? Which is really disrupting people’s religious rights and their freedom of speech and their right to worship. And I will say, I did not believe in disrupting the religious service. I thought we should just be protesting outside, that it was going to cause a backlash against us.

BLACKMON: It’s funny how history repeats itself, because we’re back to that same argument with the trans issue. I’ve even heard some trans people say, “Well, it was taken too far.” Or, “It was maybe pushed too much too soon.”

BELVERIO: I think it hurt a lot of trans people who aren’t radical activists, who really just want to live their lives quietly after they’ve transitioned. And I think that during the Biden administration, these issues were pushed too far into the public sphere, into people’s faces. In middle America, we have working families who are just struggling to survive, and suddenly they’re hearing about all this radical gender ideology. I think it was just too much too soon, and I think some of that contributed to a backlash.

BLACKMON: Your particular drag is pretty unique. It’s not RuPaul drag, where it’s very entertainment-based. Glennda, to me, is very intellectual and softly political. You’re not trying to club people over the head with your message; just being present in their space is a political act. Is that a fair assessment?

BELVERIO: Absolutely, and I think the style of drag that you’re describing is something that came out of the East Village drag scene. Before that, there was the whole tradition of drag being about high glamour and also just commenting on women’s sex roles and satirizing them or parodying them, but also honoring women and Old Hollywood. The drag that came out of the performance art scene at Club 57 and the Pyramid Club was rough around the edges and kind of messy and DIY.

BLACKMON: I believe I’ve heard the term called “genderfuck.”

BELVERIO: I always thought of genderfuck as this kind of radical theory thing. You have a beard and there’s glitter in the beard, but then you have makeup and you’re sort of in demi-drag.

BLACKMON: That’s a great word. Demi-drag.

BELVERIO: I learned about drag just by going to the Pyramid Club, and these people were my idols: Hapi Phace and Hattie Hathaway, they were my drag godmothers. And it was messy, it was DIY. It was commenting on the art form of drag itself because drag had become kind of square in the eighties. I was very influenced by 1960s fashion, but also the Warhol drag queens. I really liked their style. Drag in the 90s, we weren’t trying to be great beauties, but even within the East Village scene itself, there were dueling tribes. The drag at the Pyramid Club was more satirical and messy. And then there were the Boy Bar Beauties, where drag queens like Mona Foot performed. And of course there was cross-pollination between the two clubs, but that scene was really about being flawless.

BLACKMON: Was it still about being counter-cultural, or was it almost like they were trying to blend in with the mainstream?

BELVERIO: No, it was still a very counter-cultural because drag was just not accepted and gay people were hated and blamed for AIDS, so I don’t think the queens that were performing at Boy Bar were thinking like, “I’m going to be on Broadway.”

BLACKMON: For the Interview readers, tell us about the New York City gay experience in the 1980s and 1990s? There’s the low of the AIDS epidemic, but you have the high of a New York Club scene that was world-class. It must have felt like the world could fall off at any moment.

BELVERIO: It was different than now just because, again, New York was cheap. You could find a cheap rent-stabilized apartment, which is actually where I’m sitting right now. It was a balance of living under this fear of losing your friends or losing your own life and then creating your artwork and just having this wild time. The East Village was like the wild, wild west. It wasn’t like it is now. I remember people didn’t want to come to the East Village. Gays who lived in the West Village and Chelsea, they were like, “Why go to the East Village? There aren’t even any restaurants over there. There’s nowhere to go.” There were like. three restaurants. That kind of lifestyle in New York City is probably virtually impossible now because New York has basically become a forced labor camp. Some young people are very conservative. When I was in my twenties, we were going out and drinking and partying, and I don’t even hear young people talk about that anymore.

BLACKMON: There are no clubs anymore.

BELVERIO: I’m told that they’re in Brooklyn. There must be. I mean, I wouldn’t know because why would I want to go there? I’m 30 years older than everyone else in the room. I started watching this reality show that’s not on the air anymore called We’re Here. It’s about three winners, I guess, from RuPaul’s Drag Race, and they travel cross-country to do outreach about being gay and help young drag queens shape their act. The best moments are when these queens are not in drag and they’re these effeminate sissies. It’s more subversive and more powerful to be an effeminate out gay man in this culture, a kind of sensual feminine gay man. But then it comes to the part where they’re shaping these young drag queens performance styles, they’ll go into a theater and these drag queens will kind of audition for them and they’ll be whispering going, “Oh no, she needs help.” Or, “That makeup is rough.” To me, that is the worst kind of cultural imperialism. It’s become this kind of brand, the RuPaul brand, this is the only style of drag you can be.

BLACKMON: And that’s way easier than going against the grain. I feel like people are weary right now. It’s fight after fight.

BELVERIO: Yeah. I feel that way. I applaud people who are getting out in the streets and making noise and getting arrested. But if it was that effective, then how did we get to this point where we’re now living under total fascism? It’s like we’re living under Pinochet in Chile. I feel like a lot of street activism is just group therapy, because if it was effective, we wouldn’t have Trump’s second term, we wouldn’t have Roe v. Wade being overturned. Where are the victories? I think we need new tactics now. I don’t think just making clever signs and marching down Fifth Avenue is going to do it.

BLACKMON: You need something more substantial, you mean?

BELVERIO: We definitely have to figure out a more effective way of fighting back because things are just going to get worse. Of course, I’m a registered Democrat, I’ve always voted Democrat. My friend Camille Paglia sometimes votes Democrat, sometimes third party. Even though in this alt-right scene, they love her.

BLACKMON: Yeah, I saw a picture of her with Jordan Peterson…

BELVERIO: She did one interview with him and it got a lot of traction. I’ve avoided watching it.

BLACKMON: You recently spoke at the National Gallery of Art.

BELVERIO: Yeah, that was two years ago, for the 30th anniversary of Glennda and Camille Do Downtown.

BLACKMON: How did that go?

BELVERIO: It was definitely the biggest venue that my work has been shown in. The theater there is huge. We showed [the documentary] Glennda and Camille Do Downtown, and then we showed the video I made with Joan Jett Blakk, who was the drag queen who ran for president. It was an honor. I remember walking through the museum with my friend Corey going, “Oh my god, I can’t believe that my work is showing here.”

BLACKMON: It’s interesting because Kim Sajet of the National Portrait Gallery was just fired by Trump for being too “woke.” Had you been scheduled to give your talk on drag and gay sexual politics now, they probably wouldn’t have let you.

BELVERIO: Well, that’s the thing. The National Gallery receives federal funding, so I doubt that they’re going to have any queer programming now. They had to stop their DEI program immediately. It’s frightening. I mean, this is fascism when these kinds of things happen. When you’re stifling free speech, the First Amendment, then you’re living under fascism.