Tom Ford

Tom Ford is without question one of the mostrecognizable fashion designers America has ever produced. His sleek, hypersexual work at Gucci and Yves Saint Laurent was a defining force infashion from the mid-’90s to the mid-’00s. Ford was so successful in this first chosen profession—even launching his own eponymous label after leavingGucci in 2004—that he hardly needed to start over and acquire a second career. But anyone familiar with Ford—or even his runway inspirations—could hardly be surprised by the news that the designer would eventually turn his attention to making movies.

The result is Ford’s debut as a filmmaker, A Single Man, an adaptation of a 1964 novel by Christopher Isherwood. The narrative centers on a college literature professor named George (played by Colin Firth), whose unwavering despondency over the death of his longtime companion (Matthew Goode) drives him to decide to take his own life. Of course, it is the very moment when George prepares to say goodbye to the world that it opens up for him. The film charts the course of what he plans will be the last day of his life: He courts an unexpected relationship with a student (Nicholas Hoult), meets a handsome hustler outside a Hollywood liquor store (played, in fact, by Tom Ford model Jon Kortajarena), and clashes with his closest friend (Julianne Moore).

A Single Man is not without Ford’s clean lines and meticulous veneers but, as a director, he tackles the rush of emotion that comes with loss with masterful subtlety and rhythm. The 48-year-old Ford isn’t claiming that he’ll never return to his starring role in fashion—the success of the Tom Ford menswear brand has exceeded expectations, and he is preparing to launch a womenswear line at some point in the near future. But film, a longtime passion, is now his central focus. Here, Ford speaks to director Gus Van Sant about making movies, the seduction of youth, and why fashion just wasn’t enough.

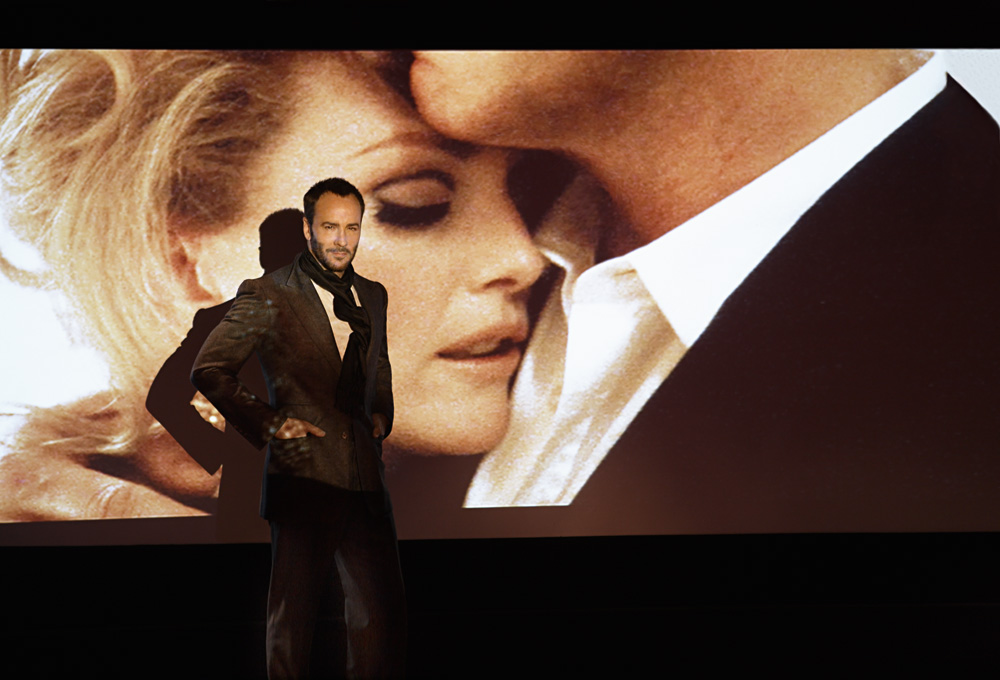

Photo above: Tom Ford in London, October 2009. All clothing: Tom Ford.

I was going through something of a crisis . . . having spent a good deal of my life really, really wrapped up in the material world and neglecting a certain side of who I was. I suppose I’ve always been quite spiritual and intuitive, and I struggle, as many of us do, to live in the present moment.Tom Ford

TOM FORD: Hi, Gus. Where are you?

GUS VAN SANT: I’m in Portland, Oregon, where I live. I’m just starting up a film we’re going to shoot in a few weeks.

FORD: I think Nick Hoult read for it. He said it was one of the worst readings he’s ever given. [laughs] He’s a very sweet kid.

VAN SANT: He’s amazing—especially in your film. He did come for a reading, and I was going to ask you about him. I met him right when you were shooting A Single Man. Wasn’t that about a year ago now?

FORD: Yes. The film was shot in 22 days in November and December [2008].

VAN SANT: I tried to meet him in London before that, when I was scoring a film, but he wasn’t there, so I met him in L.A. during your shoot, and he was kind of still in that character.

FORD: With his American accent and blond hair?

VAN SANT: Yeah. [laughs] I think he gave a pretty good reading this time around.

FORD: Well, I’m a big fan of yours. I’m very nervous to talk to you. I’m never nervous to speak to anybody, but I am such a fan of yours. Mala Noche [1985] is one of my favorite movies, and so is To Die For [1995]. But I like all of your films.

VAN SANT: Were you in New York in the ’80s?

FORD: Yeah, I moved to New York in 1979, and I knew Andy [Warhol]. Actually, I met him the very first month I was there. Did you know Ian Falconer? Ian was my first boyfriend. For a while, I was quite friendly with Fred Hughes [Warhol’s business manager] and a lot of people at the Factory, so I knew Andy pretty well. By the mid-’80s, I had drifted away. You sound a little bit like Andy, actually.

VAN SANT: I do? Oh, my god. [laughs]

FORD: I don’t know if you’ve been told that. Your speech pattern is just slightly, slightly Andy.

VAN SANT: I have been told that, but I never met him, so I only know him through images. But Paige Powell [former Interview associate publisher] once told me that, and so did Francesco Clemente.

FORD: If you just add the word “great” to your vocabulary a lot, you’ll be there.

VAN SANT: One of the reasons that I met Paige was because I was writing a screenplay about Andy. It was loosely based on the book Holy Terror [by Bob Colacello]. My real estate agent in Portland knew Paige and said, “You have to meet her. She worked with Andy.” She was one of my main sources, especially with dialogue and speech patterns. So we became really good friends back then. This was in, like, ’91. The movie was never made. [laughs] Maybe I should go back to it. . . . A Single Man is from a book by Christopher Isherwood that you first read a long time ago, right?

FORD: Yeah, I read it in the early ’80s when I moved to Los Angeles. I developed a crush on the character George. Ian, my first boyfriend—well, we weren’t together anymore—was living with David Hockney, so I met Christopher through him. We weren’t friends, but meeting him really cemented the passion I had for his work. One of the things I love is the way he depicted gay characters in just a simple, matter-of-fact way. Their sexuality was never really an issue for the characters. Of course, most of his characters were autobiographical. But the spiritual element of the book didn’t strike me until I picked it up again in my mid-forties. I always knew that it was written in the third person, but I didn’t realize that it was the true observation of the self. And that was what spoke to me at that particular moment in time in my life.

VAN SANT: Oh, wow.

FORD: I was going through something of a crisis of the same kind, having spent a good deal of my life really, really wrapped up in the material world and neglecting a certain side of who I was. I suppose I’ve always been quite spiritual and intuitive, and I struggle, as many of us do, to live in the present moment. We end up feeling isolated most of the time. That’s what the story is about for me: that isolation we can all feel even though we are surrounded by people. And in my script, George decides to kill himself, so he goes through his day in a completely different way, seeing things in a completely different way, andpeople respond to him in a different way because he is different. He thinks it’s his last day. For the first time in a long time, he’s actually living in the present.

VAN SANT: It’s a really beautiful description of that type of isolation. So many of us live in that frameof isolation. I think even well-adjusted people could be enthralled by and relate to the predicament in this film, which is impressive. Personally, I can entirely relate to this character. Then there’s the character Kenny, the college student, and the hustler in front of the liquor store. They are these angels that pull the character to the side, sort of trying to rescue him. I liked that they appeared out of nowhere and there’s no particular reason for it.

FORD: The reason is that he’s just looking at everything in a different way. For the guy at the liquor store, George is just stunned by this guy’s beauty. He doesn’t want sex from him. He just wants to look at him and kind of drink him in, in a way. Kenny, though, is a literal angel—or was meant to be. At least that’s what I intended him to be. Maybe that’s not how it got translated.

Photo above: Fragrance: Grey Vetiver by Tom Ford.

I don’t know if you’ve ever been obsessed by anyone. We all have. I’ve been a stalker at times in my life. You know, where you sit outside someone’s house hoping you’ll catch a glimpse of them through the window. Tom Ford

VAN SANT: Yeah, he definitely is. I mean, you dressed him like an angel, with the mohair sweater.

FORD: Yeah. I had to brush that sweater and put hairspray on it the whole time, because mohair—you know. It just kept getting fluffier and fluffier and fluffier.

VAN SANT: It was very fluffy. Kenny is amazing. Only a couple of times in my life have I encountered a character like that. They’re sort of insistent and coming at you for no apparent reason. Like, you just can’t figure out what this person is up to. Is he like that in the book, too? How does Isherwood describe him?

FORD: He’s one of the characters truest to the book. I had to take quite a lot of liberties with the book because there’s no plot in it. It’s an inner monologue. It’s a beautiful piece of prose, but nothing happens. There’s no planned suicide. There’s nothing external to tell the story, unless you just did one giant voice-over, which I didn’t want to do. So I had to create external situations and scenes in order to tell the story and let the audience understand what George was feeling. Kenny is quite true to the book, though. The hustler doesn’t exist in the book. But Kenny does. He’s like the bookend to George. He’s drawn to George. He’s attracted to George. He doesn’t necessarily know why. He’s at a change in his life—he’s changing from a young adult into a man. He’s figuring out who he is. George is also changing, moving to a different stage of his life—albeit one where he can’t see his future. All of the principal characters are at a crossroads. So Kenny and George are drawn to each other. When I was young, I was always attracted to older guys. I live with someone. I’ve been with him for 23 years—he’s older than I am. But now, of course, as I get older, I’m attracted to people that are younger—mostly, I think, because you see the world through their eyes and their view isn’t as jaded as yours is, so everything becomes fresh. Interestingly, the actor who played Kenny, Nicholas, was 18 when we shot the film andColin was 48, which is exactly how old Christopher Isherwood and [portrait artist] Don Bachardy were when they met. I don’t know if you’ve seen that wonderful documentary Chris & Don: A Love Story [2007]?

VAN SANT: Yeah, it’s amazing.

FORD: It’s so great. Anyway, George is drawn to Kenny because he is giving him new life. And Kenny is drawn to George because he likes the way that he thinks—George doesn’t think in a conventional way for a 1962 college professor, and that’s what Kenny is attracted to.

VAN SANT: That’s the main thing he’s attracted to?

FORD: Yeah, in a sense. He’s questioning things, and he suspects that this man has the answers.

VAN SANT: What’s intriguing is that the character isn’t really resolved. We’re not really sure what Kenny is striving for. I guess he’s striving for all of it. He’s looking for a mentor, but he’s basically a stalker.

FORD: He is a stalker! He’s absolutely a stalker. I don’t know if you’ve ever been obsessed by anyone. We all have. I’ve been a stalker at times in my life. [laughs] You know, where you sit outside someone’s house hoping you’ll catch a glimpse of them through the window. That kind of isolation leads you to do that sort of thing, where you feel you could potentially connect with someone else. It’s not that hard to become a stalker.

VAN SANT: Did you show the film to Don Bachardy?

FORD: Don read the screenplay after I finished it. Don’s actually in the film. We pan across a sofa in the faculty lounge, and my boyfriend is on one end and Don is on the other. He even has a line. He sent me a long letter after he saw it, saying that he loved it and he was relieved. [laughs] He was nervous because it was one of Christopher’s favorite books that he had written.

VAN SANT: Do you relate to any of the characters in particular?

FORD: I don’t know. How do you feel when you write a character? I mean, I think you can’t help it. When you write a character and their dialogue, you can’t help imagining how you would be acting if you were them. You kind of have to relate to all of them. It’s the most personal thing I’ve ever done. I don’t think you can compare it to fashion. They are two completely different things for me. So there was a lot of me in all three of the principal characters.

VAN SANT: How did you start out in fashion?

FORD: First of all, I think people who are attracted to the fashion industry are people who are really insecure and looking for a certain identity. I think that’s initially how people are attracted to it. And I’m sure it’s true about other industries as well, but in particular with that industry. I started out going to Parsons [in New York], where I was studying interior architecture. I realized that it was too serious for me. [laughs] Then I was living in Paris and had an internship at Chloé and realized that it was the one industry suited for my skills, talents, and ambitions. I went back to New York and got a job and started working. I didn’t work on Seventh Avenue too long. I moved to Europe in 1990, and I’ve lived mostly there for the past 20 years. I just worked my way up. But fashion, for me, is very different from film. Fashion, for me, is a commercial endeavor. It is artistic, but I’ve never approached it as though I were an artist. There are fashion designers who approach what they do as though they’re artists. But the thing I approach like that is film—and I hope it continues to be. This film in particular was just pure expression, which is new to me—creating something simply because I felt compelled to create it as opposed to thinking about it as something to sell and market as an end or a goal. In fashion you make something and the goal—at least for me—is to sell it. So I design into a box. I know what I need, how many I need, how they should be priced. I’m not saying it’s not an artistic thing; you can be very creative about it and you can love it. And I can get as excited about making a beautiful shoe as a sculptor can get making sculpture. That may sound pretentious, but you know, a shoe is a freestanding object. It is a sculptural thing. And if you’re someone who likes working with forms and shapes, that can be amazing. But the thing about fashion that’s unfulfilling is that it is so fleeting. You can look at fashion in a museum, and you can admire the detail, the stitching, the way it’s constructed. But it never has the power that it has the very first time you see someone wearing it and it jars you a little bit, because it’s new, because it’s different, and because there’s something about it that captivates you because it’s beautiful. That doesn’t last very long. A few months later, it starts to fade. A year later, you’re bored with it. You’re ready to move on. Whereas when you watch a film, you’re immediately sucked back into the present, or the time in which the film is taking place, and you’re led through all those emotions all over again, as though they were occurring for the very first time. That’s an amazing thing.

VAN SANT: It is, yeah. Well, I think that you can look at film either way. Film can be like you’re saying fashion is—something to mark a certain moment.

FORD: Absolutely.

VAN SANT: I tried to design a coat once. I reached a point where I realized that warehousing and shipping were involved, and it scared me.

I think people who are attracted to the fashion industry are people who are really insecure and looking for a certain identity. I think that’s initially how people are attracted to it. Tom Ford

FORD: Wait. You designed a coat to sell?

VAN SANT: [laughs] A coat, yes. I designed a coat.

FORD: When was this?

VAN SANT: It was about 10 years ago. I used to have a coat, like a Chinese worker’s jacket. I used to wear it around, and eventually I lost it.

FORD: Just send it to me. I can make you a copy pretty easily. [laughs]

VAN SANT: Really?

FORD: Yeah. I’m so used to doing it on such a large scale. When I was at Gucci, we did $2 billion a year in sales for just that one brand. You know, fashion is one of the largest businesses in the world—if you count growing the fibers, manufacturing, selling, and retailing. So you have to be used to thinking on that scale if you’re going to design in a global way. The business of fashion comes fairly second nature to me at this point. Seventy percent of our business was done in our own stores, and we controlled exactly what was bought and how it was bought. When buyers would come in, they would have minimums, and then they had a core collection that they had to buy. If they didn’t follow our guidelines, if they didn’t maintain the shop properly, if they didn’t use the right flowers, then we would drop them. I do that now even in my own business. I have my own freestanding stores, which is why it’s so interesting handing over your film to distributors. It’s really hard for me because I’m used to following not only the design of the product but then how it is advertised: Every single ad layout in the world comes through my office. If it has to go on a bus, I look at the format. If it has to go in a newspaper, I look at the format. Every single step, every party that happens—the hors d’oeuvres have to be this way, and the waiters get put through hair and makeup so they look that way. It’s all controlled. So when you let go of a film to a distributor . . .

I have to say, it’s really terrifying for me.

VAN SANT: You could get involved in that side of it.

FORD: Oh, I’m getting involved. I’m trying to. Depending on your contract with certain distributors, they technically have the legal right to say, “I’m tired of dealing with you. Fuck off. I’m going to make the DVD case look like this!” [laughs] But I’m definitely involved. I’m 48. I don’t know how I’ll ever be able to work at this point with someone over my shoulder. I just hope I can keep making films that I have control over. It’s the only kind of thing that I can do.

VAN SANT: I think you can do it if you just set it up that way. I’ve made smaller-budget films, probably in an effort to try to have control. There are other ways of going about that. . . . You can just fight.

FORD: Well, at this point in your career, you can see you’re in control, can you not?

VAN SANT: I guess so. I’ve always sort of had the lack of self-confidence to say that. . . .

FORD: Oh, come on! You have to just say it!

VAN SANT: I think people would listen to me by now. My style is, “This is so cheap, you’ve got to give me control!” Your style is, “Just give me the control.”

FORD: “Give me the control, don’t ever come on the set, and I’ll show it to you when it’s cut.”

VAN SANT: So you’ve been living in London lately?

FORD: Yeah, I’ve been living here for a long time. I travel pretty much constantly. I have a house in L.A., a small office in L.A., and then I sometimes live in Santa Fe, New Mexico, which is where I grew up.

VAN SANT: You grew up in Santa Fe?

FORD: I did. Are you running out of things to ask me? [laughs] I can hear you hesitating.

VAN SANT: No. I’m just terribly hungover. [laughs]FORD: You know, I used to always be hungover until I quit drinking.

VAN SANT: Yeah, I should quit drinking.

FORD: I don’t know. If you don’t need to quit drinking, you shouldn’t quit drinking. I used to really love to drink, and especially living in London, you know, it’s just built for drinking. . . . [laughs]

VAN SANT: A Single Man is a beautiful film. Was it all shot in Pasadena?

FORD: It was shot in Los Angeles, from Malibu to Pasadena to Glendale. And because it was in L.A., it was a larger crew than I would have liked. It seemed like an army of people with vans and trucks. It was a small budget but a lot of people.

VAN SANT: That’s a strange experience, isn’t it? I’ve learned to live with that. You have tons of people who don’t have anything to do with your film. They’re just kind of on the set of a film. When I first experienced that, I really wasn’t sure what was going on. But you’ve done a lot of photo shoots. You’re probably used to something like that.

FORD: I am. Even in fashion, it’s become ridiculous—60 people to take a still photograph. I’ve started taking my own because I got so sick of all of that. I work with my one photo assistant, and a model, and hair and makeup, and that’s it. And, you know, I worked a good bit with Helmut Newton and with Richard Avedon, and the other day with David Bailey. For that whole school of photographers, it’s always been one assistant, one key light, one camera, one backdrop. And these guys worked on film. No one works on film anymore. I don’t shoot on film: That’s the only reason I can be a photographer. To be a photographer now, you just have to kind of catch a base image, and then you can rebuild it, rework it, recolor it. Those old guys like Newton and Avedon—and [Irving] Penn, who just died—were just incredible in the way they could pull off the images they did on film, with no retouching. They truly understood the mechanics of their craft. For most photographers today—I won’t necessarily mention names—you see a picture of 10 people in a magazine, and none of those people were shot together. They take the best head from here, stick it on the best body from that shot, move that over there, and you fill in, which is fine, but that’s a different kind of art—an impressionistic way of interpreting something. I don’t necessarily think it’s a bad thing, but it’s a different way of working.

VAN SANT: So, what are you doing today?

FORD: I’m getting ready to take a bath and go out to dinner. My day is over.

VAN SANT: Where are you going to dinner?

FORD: I am going to dinner at a place called Mark’s Club [in London].

VAN SANT: Mark’s Club. Is it in the same area as The Groucho Club?

FORD: No, it’s not. It’s in Mayfair. It’s owned by the same guy who owns Harry’s Bar and Annabel’s. It’s very old-fashioned. I love Annabel’s, actually. Where else do you see those kinds of people dancing around on the little disco floor with lights in the ceiling, and all those cute military boys coming through in the nighttime, after all those debutante parties?

VAN SANT: Debutante parties?

FORD: They’re all still going to Annabel’s!

VAN SANT: I don’t think I’ve ever seen any other place with the kids, like 18 or 19, who are all dressed up and going out. You just don’t see that anywhere.

FORD: They’re in London, still dressed up and going out—and more drunk and taking more drugs than just about anywhere. I mean, the surface is polished. It’s the other things that are going on that are less than polished.

Gus Van Sant is an Award-Winning writer, producer, and director based in Portland, Oregon.