IN CONVERSATION

The Kills Talk to Ethan Hawke About God, Mortality, and Trashy Art

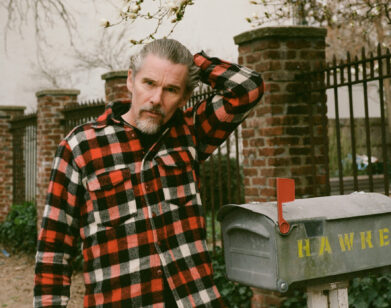

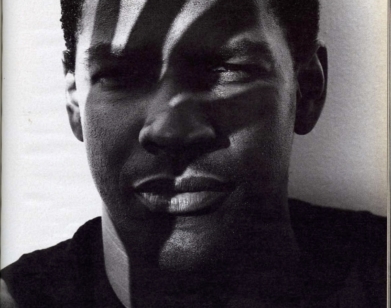

The Kills, photographed by Myles Hendrik.

Last fall, Jamie Hince and Allison Mosshart of The Kills released their sixth studio album and first in seven years, God Games. And like its title suggests, the rock duo was thinking about matters of the divine. “I’ve always questioned why I’m an atheist, but in music and when creating I like having god around,” said Hince, who’s been making music with Mosshart since 2001, when the pair first crossed paths in London. Ethan Hawke, for his part, has his own theories about the presence of god on their latest record. “When a lot of us are left alone in our room, there’s some kind of awareness that happens that is extremely comforting to be around,” said the actor and longtime Kills fan, calling Hince and Mosshart, back in New York after filming a pilot for TF in Tulsa, Oklahoma. “Human creativity,” he added, “is an act of faith.” As the band wrapped up two shows at Webster Hall, they got deep with Hawke about out-of-body sensations, reality TV, and the pursuit of happiness.

———

JAMIE HINCE: Hello, Ethan.

HAWKE: How are you doing?

HINCE: I’m good. I look like I’m in the hospital bed, but I’m not.

HAWKE: I just landed this morning back from Tulsa, so I was sorry to miss your New York shows.

MOSSHART: It was very fun. It was a lot.

HAWKE: Are you in deep recovery right now? Are you on IV drips?

MOSSHART: We have to play DC tonight, so I don’t know how we’re going to do that with our legs and everything.

HINCE: Yeah, I was thinking about that when I was trying to adjust the lighting in my room and I walked over to the lamp. I realized it must’ve been a good show last night because my left heel really hurts.

HAWKE: Well this new record is just fantastic.

MOSSHART: Thank you.

HAWKE: I’ve been listening to it nonstop. When I put it on, it felt like seeing a friend again after a long time. When you have a really good friend and you haven’t seen them, it’s almost like no time has gone by. It doesn’t matter that it’s been a while.

HINCE: I love that.

HAWKE: I read a little bit about the notes on recording the record and it sounds like it’s a very dangerous undertaking, to talk about god.

HINCE: I didn’t think about that at the time, but I just started with word association really. I liked this idea of writing godless gospels. I’ve always questioned why I’m an atheist, but in music and when creating I like having god around.

HAWKE: Can I offer a theory about that? Other people make god so uncomfortable because when you come against their doctrines and zealotry, it gets really abrasive. When a lot of us are left alone in our room, there’s some kind of awareness that happens that is extremely comforting to be around. Human creativity is an act of faith. As soon as you get on stage and play a guitar, the subtext of what you’re saying is that our time here together matters and that communication matters. Making sense out of the universe matters. When you start saying that, somehow you’re talking about the divine.

MOSSHART: I think about that all the time. Where do songs come from? Sometimes I don’t feel responsible for them at all. When I’m playing on stage, I don’t really know how I’m doing it. I don’t know what this energy is that’s suddenly there. I always think it’s like, 95% the audience and 5% the fact that I bothered to walk up there. It’s hard to explain, especially really amazing shows that I don’t remember at all. It’s like I went somewhere else. Those are the really great ones.

HAWKE: That’s always my test. I learned this a long time ago as an actor: after a show, if you think it went well, it didn’t because it means that some part of you is sitting outside of yourself saying, “Gee, I’m great.” The audience smells that and it makes them sick to their stomach. If you think you did badly, you’re probably right.

HINCE: How does it work when you are working? You obviously get an immediate reaction from the director or, if you are directing, from the actors. But it’s a long process before you get an audience reaction.

HAWKE: I was really thinking about acting on stage where you do have immediate feedback. It feels like electricity is being shot through you. I love the aspect of live performance. On film, I imagine it’s a lot more like being in the studio. If I go on stage it’s like a dream. The show starts and two-and-a-half hours later, I’m at a curtain call and I’m waking up from a dream.

HINCE: I know. You’re pacing around in the dressing room and just thinking, “Why the fuck am I doing this?” So much panic and fear, because it’s your human self, but then you walk out there and you can’t be ordinary, you have to sort of transcend into some superhuman. There’s a weird elation that you can’t explain either. I love that an hour ago I would’ve done anything to get out of this.

HAWKE: Yeah. I’ll be backstage, a nervous wreck, hands ringing, a little sick to my stomach. Drinking tea with four sore throat lozenges at the same time. Then, an hour-and-a-half later I’ll be screaming, strangling somebody on stage. You couldn’t quite imagine that the same person who is being so bold on stage could be such a little mouse. There’s this responsibility that kicks in when you get on stage all of a sudden, to be worth other people’s time. These people paid money and they want to believe I’m better than a cricket.

HINCE: It is complicated with music because everyone really wants to know. They pour over your lyrics, they think everything’s autobiographical. They demand authenticity from you in a way that I don’t think they do in a lot of other industries. They allow you to be a character in other industries, in other art forms. They demand this–

MOSSHART: Magic show.

HINCE: It has to be authentically you, and it has to be a magic show.

HAWKE: It’s such a riddle because if you go up and do magic tricks, they smell bullshit. You actually have to set yourself on fire. Some part of you has to cut a vein and still live.

HINCE: Luckily we can do that.

HAWKE: [Laughs]. Tell me about the writing process between the two of you. Your collaboration has been so long. Did it work differently on this record?

MOSSHART: It’s always kind of similar. When we started the band, we lived in different countries, so we wrote separately and then we gave each other songs like gifts. That’s how I always thought about it. Sometimes we would put it in a box and send it across the ocean, then email was invented, but it took a while. So we typically write alone and write a whole song and then share it and edit and work on it together at the end. It has to be quite solitary.

HINCE: Yeah. No one else can be involved and then you come together and it’s a commune when you’re making it. We don’t interfere with each other’s writing process at all, unless there’s a hole in it and it needs to be filled with something, but we write very separately.

MOSSHART: And secretly.

HINCE: It used to be the case that we would go on tour and collect things. I would overhear conversation. It was real eavesdropping, or “found conversation,” as I called it. I would sit in a cafe or in a bar and I would write as fast as I could verbatim and what was going on around me. I would use that for songs or we would take photographs or paint things in the van or the bus or in our hotel room and that would always inform our next record. We would lay all these things out and then make a record out of that. It’s not so much like that now.

MOSSHART: It’s a little less beat poetry these days.

HINCE: Back then I was trying to make sense of the world, my environment. Now, I’m trying to make sense of my fucking feelings and my fucking thoughts. Why can’t I just let things run their course?

HAWKE: Do you feel like each album is a marker in the time of your life? One of the things that I find really pleasing about the experience of putting my thoughts on paper is being able to let them go. Sometimes I have these thoughts that I can’t stop thinking about something.

HINCE: Do you think you have to suffer to do that?

HAWKE: I don’t believe you need to, but lot of us choose to. I’ve watched so many friends over the course of my life, and we made that joke earlier that the audience really wants to see you set yourself on fire. I have several friends that have really taken that to heart. They feel a desire to go on stage and really give the piece of themselves so much that they somehow get lost and can end up really hurting themselves. There’s a delusion that hurting yourself is somehow good for your creativity.

HINCE: I used to be like that very much. I felt like I really had to live tied to a fucking train track in order to get anything out of me. I don’t feel like that now. It feels really self-obsessed now, that kind of shit.

HAWKE: Me too. I just finished making a movie about Flannery O’Connor, the American novelist. She was diagnosed with lupus when she was 24 and her father had died of lupus. When she got this diagnosis at 24 she assumed she had about six months to live. She ended up living to 39, but she never knew if she was going to see the next Christmas. Mortality didn’t need to be made up. A lot of young people feel like we have to lay on the train tracks because we want to feel mortality, we want to feel epic thoughts. We want to feel a connection to something greater than our own minute needs. You force yourself into dangerous situations to try to think more deeply. Ms. O’Connor had mortality thrust on her at a very young age so she didn’t have to manufacture darkness. The darkness was coming for her every day. I don’t know about you, Jamie, but I’m trying to be happy now.

MOSSHART: I want to be happy.

HINCE: Yeah, me too. It’s weird, when I was a teenager I loved protest music or like, anarchist punk music and I found that so fulfilling. I listen to things like that now and it really is like, “I don’t want a man shouting at me about shit anymore.” Now I want more beauty. I don’t care if it’s an ugly subject, but you have to find some beauty in it. I’m glad that I’m not in that stage of my life where I’m sort of railing against things. I want to find things that make me feel good and that inspire other people and make them feel good.

HAWKE: It must be an interesting thing, you record this record and now your job is to take it out and share it with audiences, right? How is that?

HINCE: It’s really difficult.

MOSSHART: This is the most interesting part though. The scariest part and my favorite part is going and playing those songs live and finding out, because you can see it in people’s faces if that song is meant for them or not.

HAWKE: People are funny, aren’t they? I remember sometimes when doing a Broadway show, you walk out on stage and literally I have not said my first line and two people in the front row are fast asleep. Like, “You paid so much money for these tickets, give me a chance.”

HINCE: We had this guy at a show who was standing quite close to the front like this, with both of his fingers in his ears. [Gestures]

MOSSHART: The whole show. The tallest man in the room.

HAWKE: Wow.

MOSSHART: I couldn’t take my eyes off of him.

HAWKE: It’s weird, you just have to give it away, don’t you? You don’t know there’s somebody there who’s having the time of their life and there’s another person who’s asleep and there’s another person with their finger in their ears. I don’t know why they pay all this money and come out not to have a good time.

HINCE: He didn’t think it was going to be as loud, but I’ve got no sympathy.

HAWKE: I’m at a point where I don’t like being shouted at either. Over the last decade or so, it seems that what the internet has done is just raised the volume of people shouting at each other.

HINCE: Yes. It’s what I describe as emoji politics, where there’s no gray area. It’s like, “Is it a smiley face or is it a frown? Thumbs up or thumbs down?” I like exploring the gray areas and what’s in between these things.

HAWKE: I love this quote you said, “I like occupying the space between opposites.” Emoji politics are a waste of time because the truth is, if we didn’t die, we would never be alive. If it didn’t rain, it would never be sunny. That’s why when somebody can talk about something difficult and make it beautiful, you’re getting into some really interesting areas because you’re embracing the nuance.

HINCE: I would go as far as to say I’m drawn to ugly things. I’m drawn to things that I dislike and I don’t know why.

HAWKE: [Laughs] Like what?

MOSSHART: You hate-watch stuff on television.

HINCE: Religion, I’m drawn to it even though I’m an atheist. I’m drawn to things that repulse me and then I like to find a cute little angle. Like reality TV, I hate it but I’m also consumed by it. I like to find something beautiful in it. It’s important to see what trash people like to try and understand the society we are in. That’s probably why I like all this crap.

MOSSHART: Don’t you feel like there’s so much of it anyway that you don’t have to look for more, it’s just so constant?

HAWKE: It’s going to find you.

MOSSHART: It’s going to find you no matter what, yeah.

HINCE: I’m not searching for it, I’m surrounded by it. Unless you count searching as just going onto Hulu. I know that I’m just trying to turn it into something artistic, because that’s what I understand.

HAWKE: What’s really cool about your collaboration and really unique is that the masculine and the feminine are so alive in both of you.

HINCE: Well, not so much in me.

HAWKE: It’s what makes it so the history of rock and roll. It always breaks my heart a little when I read some profile about them fighting, like Ray and Dave Davies. I’m like, “Guys, don’t fight, you’re both awesome.”

HINCE: That’s really a great example and thankfully it is a rare example, the hatred being that awful. They make the most incredible music and yet they want to hate each other.

HAWKE: I’m glad that you guys want to like each other.

MOSSHART: Yeah, me too.

HINCE: I feel like I’m the worst person in the studio. I’ve developed this thing where I talked to myself and shouted at myself because it’s too much.

HAWKE: Like John McEnroe or something?

HINCE: That’s me, I’m McEnroe in the studio. I’m not easy in the studio and the longer our relationship goes on, the more comfortable I am losing it in front of her. I have a lot of meltdowns and panics. It always has to be better than my ability, which is why.

MOSSHART: I enjoyed recording this record with you, Jamie. It was a healthy and happy experience.

HINCE: I would say it was the happiest record we’ve made. Not necessarily in terms of subject, but in terms of experience.

HAWKE: Well, I wanted to tell you how much I love the song “Blank.” That song’s incredible. It’s so moving. And I watched that video for “Wasterpiece,” the golf video. It made me laugh so hard.

HINCE: Really? It’s such a weird tangent for our aesthetic. We left that in the hands of the director.

MOSSHART: You can tell that we wrote the first three and then all of a sudden we’re golfing. On the golf course obviously, I was wearing the wrong shoes, none of it.

HAWKE: Well, listen, I want your tour to go great.

MOSSHART: Thank you, Ethan.

HAWKE: I’ll try to find you guys somewhere along the road. I’m doing a lot of traveling too, so I might be able to find you in some mysterious unknown city.

HINCE: That’d be good, we would love to see you in person again.

HAWKE: I still appreciate the time, you guys.

MOSSHART: Thank you so much, Ethan.