tributes

Cheryl Dunn on Immortalizing the Life of Dash Snow

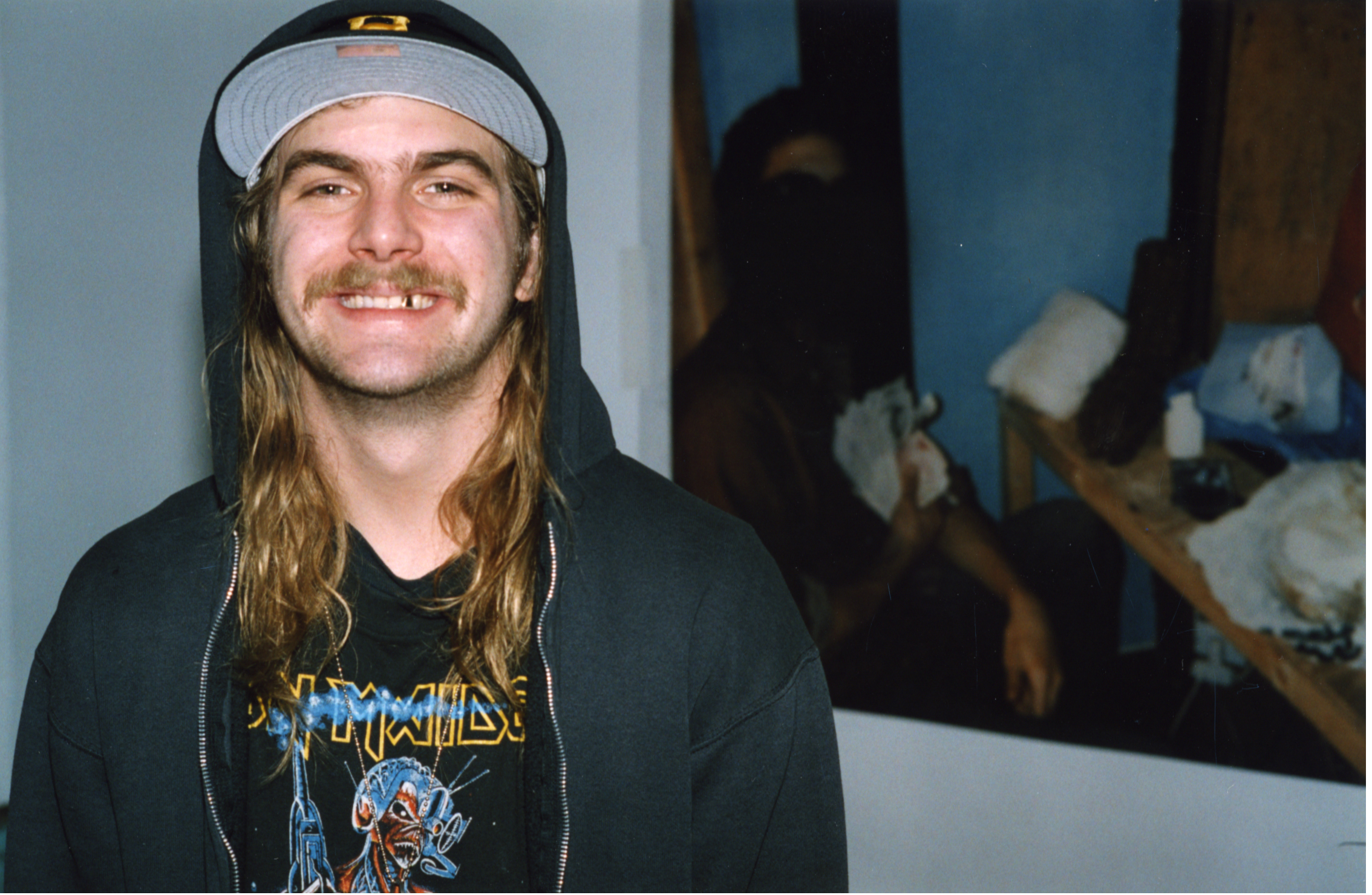

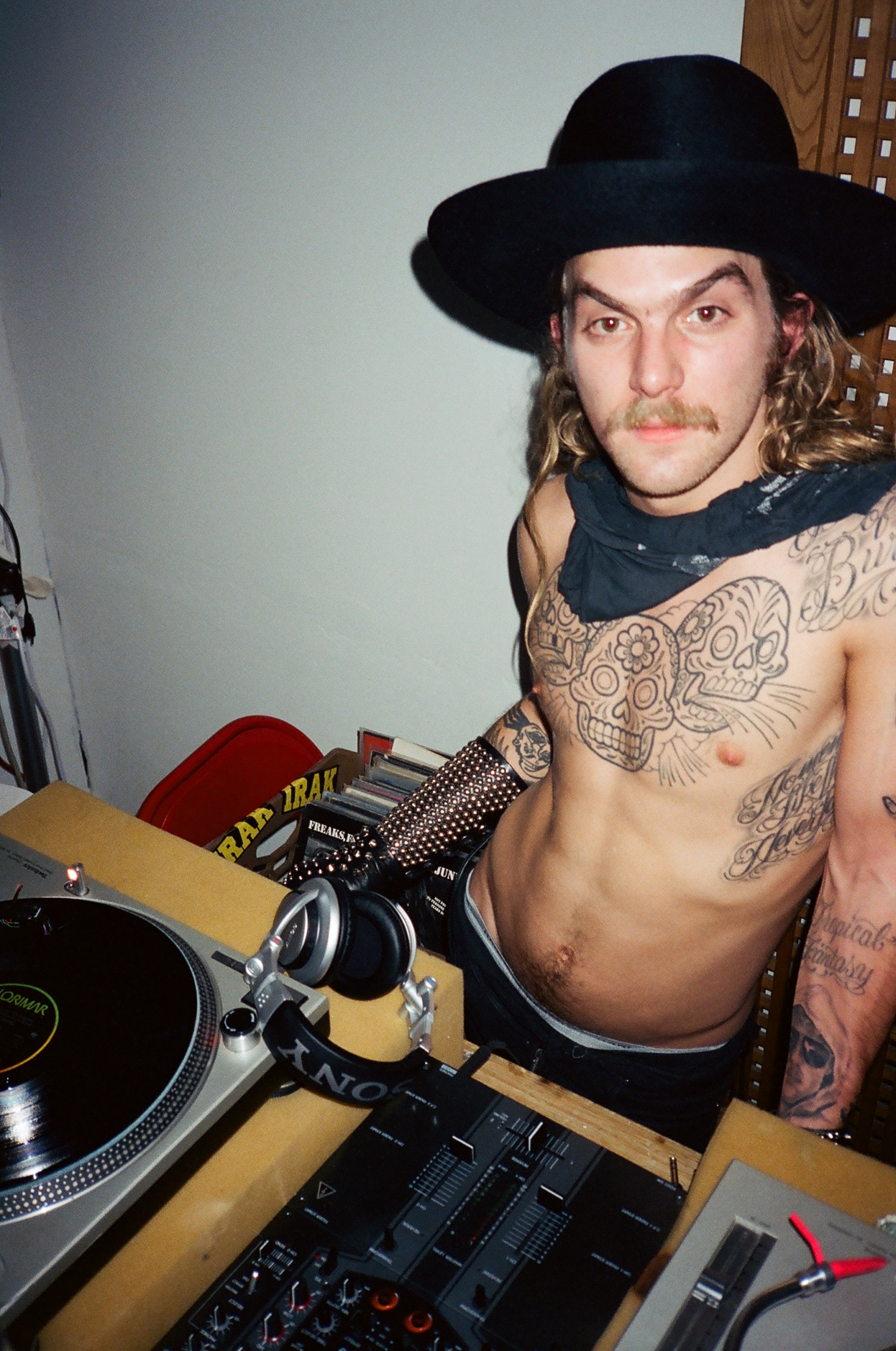

All stills from Moments Like This Never Last.

I never met Dash Snow, but thanks to the documentary by photographer and filmmaker Cheryl Dunn, Moments Like This Never Last, I feel now that I know him, that I’ve spent some crazy good times with him, and that I miss him. The 90-minute film is a personal, up-close depiction of the artist‘s raw, contagious energy, and his troubled life. The doc follows him hopping from East Village squats to rooftops, to bars, to tunnels, to parties and gallery installs, while hearing his friendly voice talking to us, reflecting and questioning everything except his own friendships. His circle of friends, the New York downtown community of artists and gallerists, also chime in with stories both hilarious and heartfelt. But the doc isn’t trapped into a bitter past; rather, it’s a celebration of free spirits who are reckless and generous enough to prompt us to make our surroundings more interesting. I spoke with Cheryl a few years ago about a documentary she wanted to do on him. Now it’s alive and out in the world.

———

ALEXANDRE STIPANOVICH: Congratulations on a fantastic documentary, Cheryl.

CHERYL DUNN: Thank you.

STIPANOVICH: There are many layers to it. There’s your own footage, night sessions with Dash Snow, during which you ask him questions, and follow him on rooftops and squats through the night. Then there is footage where you create a narrative to illustrate the different contributing voices, like the watermelon being smashed on the floor or the Barbie heads on the street.

DUNN: Yeah. My aim was to have it be as much in Dash’s own words and moving image, and of course his art. I wanted him to tell his own story as if you were in the room with him having a conversation, and to have others fill in the blanks or supplement that. I did get that feedback from a lot of friends, feeling like they got to spend 90 minutes with him again, to hear his voice. That was really the idea. Anything other than that, I wanted it to be in motion as much as possible, to really give the viewer a real visceral feeling of New York at the time, New York all the time, except maybe now.

STIPANOVICH: The city in the film feels like a jungle to explore… the rooftops, the basements, the bars, the squats around the East Village. The movie carries the sense of curiosity that he had for an endless exploration.

DUNN: Right.

STIPANOVICH: He takes us on a ride, almost under his wing. We feel imbued with his personality, much more than the strictly timeline-based documentary narrative. I find the “impressionistic” approach has more power, more life to it. Is that how you wanted to documentary to be?

DUNN: Yes, very much so. I was having a discussion with Jade [Dash Snow’s widow] the other night about that. I want you to feel something, but I’m not telling you what to feel. It’s up to you. So, I give you information, but I don’t give you all the information so that you can have an interpretation. Hopefully when you finish watching that film and someone says, “How was it? Describe it,” you maybe can’t find the words, and that’s intentional because I want you to feel it. Just like if you stand in front of a beautiful painting or you listen to a great song and critics are trying to verbalize music. I wanted to make something that you couldn’t verbalize.

STIPANOVICH: You also show his art intertwined with his real life.

DUNN: Art and artists are formed by environment and through the senses. I think the best artists have the thinnest skin because they’re feeling things. They’re feeling the environment and then they’re creating something from that feeling, and sometimes that’s dangerous, like in Dash’s case. He was a very sensitive person, and he ultimately did not survive that sensitivity. That’s why, maybe, I am compelled to make films about artists, because I feel that artists, particularly early in their careers when they’re dealing less with the business of art and more with the pure, innate need for humans to create, they have less agendas. I feel like it’s such a special time to capture artists. Maybe you don’t understand that, but maybe 10 years down the road you look at something that somebody made 10 years before and, oh my god, you start making all these connections.

STIPANOVICH: It’s also interesting to see how he was really in the flesh. His charisma really has to do with his community, or the way he would talk to a stranger. That’s really pre-internet, pre-social network.

DUNN: Well, he was very anti-technology. There were cell phones and he did not have one. So you couldn’t find him. The number for him was “Dash Jade” because you would have to call her or you would have to go on the street below his studio and yell his name.

STIPANOVICH: Didn’t he have a mirror or periscope or something?

DUNN: [Laughs] I think he had a couple cans with string. Nate Lowman told me they did that one time with the cans. They were close enough that they could do it. They tried to do that.

STIPANOVICH: That’s so funny.

DUNN: I don’t know if he would have maintained his anti-technological feelings, but I have a feeling he would have actually. He loved this turn-of-the-century, outlaw type of vibe.

STIPANOVICH: Off the grid.

DUNN: Yeah, very off the grid. Then I think he started to dress a little bit in that period.

STIPANOVICH: Yes, what great style he had.

DUNN: Yeah, he had so much charisma.

STIPANOVICH: How did you meet him? How did you decide to interview him and follow him?

DUNN: I met him at an install of a show that was happening at Deitch Projects called “Street Market.” That was a show with Barry McGee, Stephen Powers, and Todd James. It was I believe in 2000. I was asked by a Japanese publisher to document it for a book in Japan. I set up my video camera and I hung around for about two weeks–it was a quite extensive show. And he came around and helped paint and I just met him. He was such a magical kid. He showed me all these Polaroids. Then subsequently after that I was a curator for a show called “Session the Bowl” [Deitch Projects, 2002] which was centered around this big skate bowl by this art collective called Simparch. I had made a film about it at the Wexner Center and I came back to New York and I told Jeffrey Deitch, so he made a big group show around that Bowl. I said I want to put Dash Snow in it. He did a whole wall of Polaroids and there’s a photo in the movie of him and Larry Clark standing in front of his Polaroids. When I met him, I had gone out with a graffiti writer, and I was hanging around in San Francisco with a lot of graffiti writers, and I had this inside window into this world. So I just started filming these guys and girls that I knew just to have it. I shot him a lot more at that age, at 19, just to see what he was up to, for a future project that was maybe going to happen someday.

STIPANOVICH: And here it is. He did have crazy ideas for his shows… like this one at Rivington Arms where he invites Papa Smurf [the figure of an East Village squat] to sit on a couch and sing over the Charles Manson album LIE, dressed in a pink gown. The movie portrays him as always having tons of hilarious ideas.

DUNN: Oh yeah, he was a jester. He was a real jokester. He loved secrets and clues and hidden messages, and that was part of his personality, always.

STIPANOVICH: Dash crossed many disciplines: graffiti, photography, collage, installation, re-appropriation, body art, music, filmmaking, performances. His style encapsulated all that rich complexity without paradoxes. He was a whole coherent self.

DUNN: It’s true. I think that he was incredibly curious and super prolific. He just was making things all the time. When I met him, it wasn’t like he woke up and said, “I’m an artist now.” He was kind of a reluctant artist. He was the most pure artist. It wasn’t this premeditated thing; it just was. It was really from friends going like, “Dude, this is a sculpture,” and “You should show these Polaroids.” It was just his innate, pure instinct to document, to make things. Every moment of his life was just living this thing. I didn’t go that deep into the boarding school thing—as a filmmaker you have to make choices. You have 90 minutes. But that’s what I learned about that place—the censorship that they put onto the kids. They weren’t allowed to listen to music. They had books that were censored, that had words cut out of them. Kind of like jail, I guess. It was always interesting to me that he then evolved into making collages. These subversive words that were denied him as a teenager that he then symbolically scooped off the floor and then made art out of 10 years later. He just kept progressing. I think he was an amazing street photographer. Then he started directing people. I know that he was looking for me later, maybe a year or two before he passed, to ask questions about film because he really wanted to start doing filmmaking more. A lot of the 8mm in the doc is shot by him and Jade.

STIPANOVICH: I’m thinking about the bedrooms at the boarding school and the gloomy color block painted on their wall. It adds to the feeling of discomfort and censorship you were describing. Fast forward: I’m thinking about the nest or hotel bedrooms that they devastated with his friend Dan, which seems almost like retaliation from this boarding school days. Maybe there is something here about intimacy and domestic life that was robbed from him that he wants to make dangerous and rich again. Also this scene with four walls made of books, around a guy performing the Tibetan singing bowl. It’s a performance. Most of the books have bizarre, violent titles related to death (“Grim, Gruesome, and Grisly,” “The Dead Girl” etc.)

DUNN: Yeah, that was a book fort. I think he first created that for the second Rivington Arms show that he had, and then it was definitely at the Brant Foundation after his death. That footage was an outtake from the Beautiful Losers documentary, and they gave that to me. That was his studio on Bowery.

STIPANOVICH: There’s also a thesis in the movie that 9/11 was a switch for drug use in New York, with the war in Afghanistan and the U.S. being a major producer of opioids like heroin. After 9/11, heroin became more popular and basically replaced cocaine. Is that accurate?

DUNN: That’s what some of his closest friends were saying at that time. There was a lot more people doing it. Things pivoted a little bit in that direction. I do not have firsthand experience with that, but that’s what multiple people told me.

STIPANOVICH: And Dash Snow really personifies the story of that community. What do you think his legacy is?

DUNN: I think that that time in New York is a specific art movement, a decade that I think is now history. 9/11 is going to be 20 years ago. Twenty years already! He’s one of the big names in the canon of New York art history. I’m just watching the Kenny Sharf documentary. There’s a lot of archive on Basquiat and Warhol. Kenny Sharf was a California kid and he came to New York. He was a 70s kid from a sleepy town in California and he was seeing stuff that was going on in New York with Andy Warhol, and he was like, “I’m going there.” He came to New York and he became who he became. I know so many kids who have come and worked for Ryan McGinley because of what they heard about Dash over the years. Ten years is a long time and memories fade, and that’s definitely a reason why I go through this and make films. It’s so that memories don’t fade and that colors stay vibrant. My dream, and I believe for sure that when this pandemic is over and kids all over the world get to see this film, is that they’re going to come to New York. They’re going to make their own New York. The rents will be lower, artists can afford to live here, and they’re going to come. And I already have feedback of people saying that they’re inspired by this movie. It’s an interesting time that this came out right at this time. A year ago, would you imagine our lives would be like this? A pandemic? Not at all.

STIPANOVICH: No…

DUNN: Agathe [Snow, Dash’s first wife] said to me the movie was very special, and that it’s maybe better that people got to watch this movie in their living rooms and have this intimate time with him for the 90 minutes because that was really how he was. So many people say to me, “He was my best friend,” because he made you feel so special. So if you have this you-and-him time in your living room, it might have been the best situation in the end.