Five things we learned from the Basquiat documentary, Boom for Real

IMAGE COURTESY OF MAGNOLIA PICTURES

Jean-Michel Basquiat’s artistic legacy ensures that the mere mention of his name conjures up a horde of symbols: Copyright logos, SAMO tags, gold crowns atop scribbled heads. An innovator that upended the contemporary art world with his neo-Expressionist take on identity and the systems we use to assign value, Basquiat seems the perfect documentary subject, and yet he remains cloaked in mystery.

Enter Sara Driver. The filmmaker and author was right in the thick of 1970s lower Manhattan, hobnobbing with greats like Basquiat, artist and hip-hop pioneer Fab 5 Freddy, and her lifelong partner Jim Jarmusch during New York’s countercultural apex for movements like punk rock, hip-hop, and graffiti. These seemingly separate circles actually overlapped. The city was hostile, and so you needed one another to get by. “As humans, we need community,” Driver explains. “You would ring somebody’s doorbell and they would throw a sock out with the key in it.” Young, unbridled kids would shack up together in these miniature studio apartments and at hotspots like The Mudd Club, sharing drugs, romantic partners, and art ideas. The culture was fueled by urgency and sustained through collaboration. This was the environment Driver came of age in, the one that fostered her creativity. The same is true of Basquiat.

With this insider knowledge, Driver dived headfirst into his story. She spoke to her and Basquiat’s mutual friends, his roommates and bandmates, old flames—anyone and everyone who was a member of their community and knew Basquiat before he hit it big—and things changed forever. The culmination of these interviews is Boom for Real: The Late Teenage Years of Jean-Michel Basquiat. We sat down with Driver and she told us about the documentary, her own adolescent years, and why the movement they started is still relevant today. Here’s what we learned.

THERE’S STILL A LOT OF UNSEEN WORK

SARA DRIVER: What planted the seed [for the film] originally was that the New School had a panel discussion about Jean’s early life. It was mobbed and the kids were all so interested in knowing about him. About a month or two later, Hurricane Sandy hit New York. My friend Alexis Adler, we all knew she lived with Jean, because she had a mural up in her bedroom and on a refrigerator door and on her bathroom door. We knew her history with him. She had forgotten, because she’s a scientist and had been looking through a microscope for 30 years. She had forgotten that she had put away all his drawings and writings that he had left in her place and had given to her when he left. She had put it in a bank vault and it was underground and it was in the flood zone. She was really panicked and then she went to the bank and they couldn’t even find her card, it was so old. [laughs] But they found it.

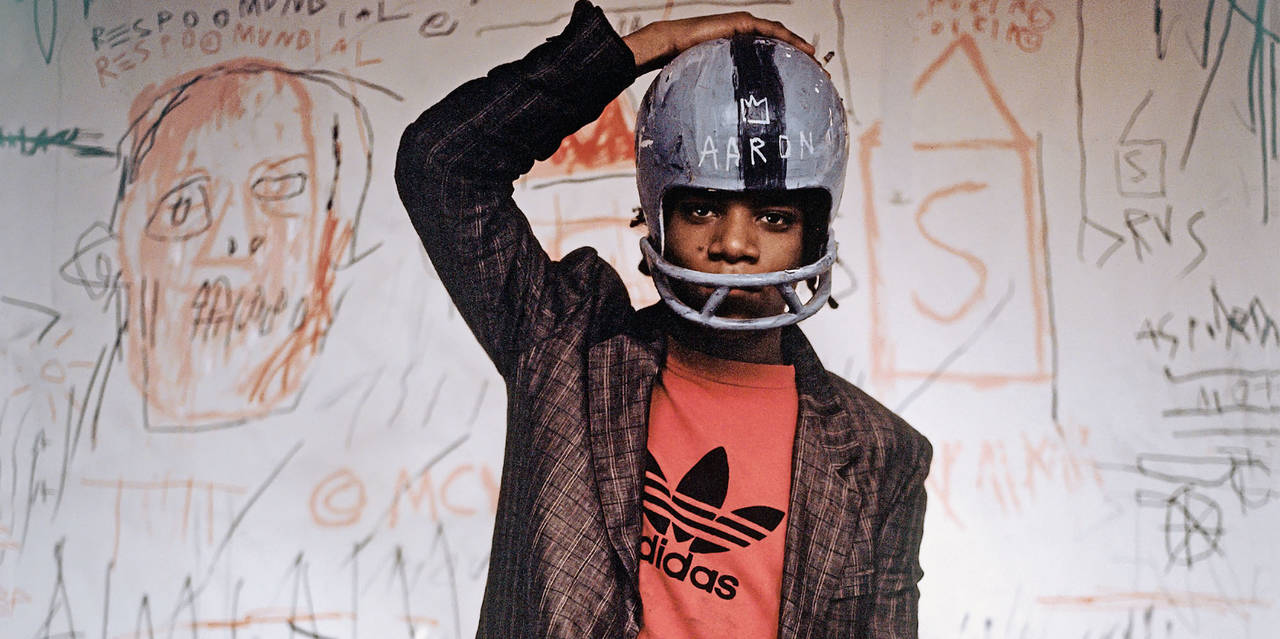

She opened it up and there were sixty works in there, his writings, drawings, a notebook. She preserved all of this work. He was so transient at that time, very few people had kept any of this stuff. Then she remembered she had a box of clothes he had painted and then she also discovered these photographs that she had taken of him when he lived with her. They are so beautiful in the film, playful and silly. I saw what she had and I was like, this is not only a window into him, but this is a window into New York at that particular moment in time. And so then I bought a camera and just started shooting, because I didn’t know what was going to happen with her archive, and I wanted to make sure to preserve what I had witnessed.

BASQUIAT WAS A PRODUCT OF A LARGER, NEW YORK ART COMMUNITY

DRIVER: The archives and the artwork and the film material, that was all people who knew me or I knew them. I feel like [the film] was made by a whole community. It wasn’t just me. Jean had something very special about him—Rene Ricard wrote this article called “The Radiant Child,” he was illuminated from inside—but we were this sort of morphing creature as a community, and he was part of it.

I thought, to show an artist and the environment that nurtured them as they were trying to find their road as an artist, since I was also involved in that environment, was such a privilege. That gives insights into who he was an artist.

HIS ART WAS INFLUENCED BY EVERYTHING

DRIVER: [Grafitti, hip-hop, the punk movement.] All these things were influencing each other, everything was interconnected. That’s why I showed them in the movie. You can’t separate one from the other. I think they try to departmentalize the art forms now, but all art forms feed each other. You can’t make movies unless you’ve gone and looked at paintings and you’ve seen other films and you’ve read literature. All those things inform us.

The sad part of Jean’s story is what would he have become? I bet he would have made films. He definitely would have gone on producing records, he loved music so much.

BASQUIAT WAS NOT CONCERNED WITH PRICE TAGS

DRIVER: We weren’t selling anything. We were doing it to amuse ourselves and to show each other. It wasn’t about money. Jean-Michel was very interesting, that he knew his value so early. He was like 18. None of us were ever even thinking about that. I was talking to Fab 5 Freddy, Freddy Brathwaite, about that and he was like, “Sara, you know, we weren’t thinking about making money. It wasn’t about making money then. It was about being together and expressing ourselves.”

Caravaggio won’t sell at auction for 3 million and Jean’s work’s selling for 112 million? It’s all about investment now. No museum anymore has been able, for years, to afford—none of the museums in New York own his work. They have to borrow it. People buy it as an investment and then they put it away in some storage thing, it’s really sad. It’s like when I look at instruments in the Metropolitan Museum and they’re under glass. It’s the same thing.

I think it must have been very heavy for him to be 27 and to have become a commodity. I think that weighed on him, because that wasn’t who he was. I think he would’ve flipped out if he saw people walking around with T-shirts. He wasn’t Keith Haring, who was into mass-marketing his stuff. Jean was a fine art painter, that’s how he saw himself.

YOUTH MOVEMENTS ARE THE FUTURE

DRIVER: Because the city was so dangerous, you had to be so alert to everything on the streets and you had an antenna of what was dangerous, what was behind you, what was in front of you. So you were also witnessing things all the time, you were seeing stories, you were seeing interactions between people, and now everybody is just looking at their phones, they’re not looking around them at the world, at a bigger world. But maybe we’re coming back to that.

This March For Our Lives is very hopeful, and for young people realizing it’s in their power. It’s not us anymore, it’s you guys. I couldn’t stop crying when I was watching those kids in Washington. And then I remember when I was 14 and I lied to my mother, I was really against the Vietnam War, there was Rennie Davis from the Chicago Seven who was going to shut down the government and I went down to D.C. to protest. It was all high school and college kids, and we stopped the Vietnam War that way. Even going to the Women’s March was so moving, it was amazing.

I hope this film instigates people to get their ideas out and be very proactive, and figure out how to make things they want to get out in the world. I hope it gives them a little courage that they can do it too, if they apply themselves and they want it enough and they want to get their signal out. I’m always saying, if I could have one word on my gravestone, it would be “instigator.” I want to spend my life trying to earn that, because then I would have lived a full life I think. With the film, it would be so great if it would instigate more people just trying things and failing and finding their way and not being so scared and so regimented.

BOOM FOR REAL: THE LATE TEENAGE YEARS OF JEAN-MICHEL BASQUIAT IS RELEASED IN CINEMAS MAY 11, 2018.