The People VS. Bret Easton Ellis

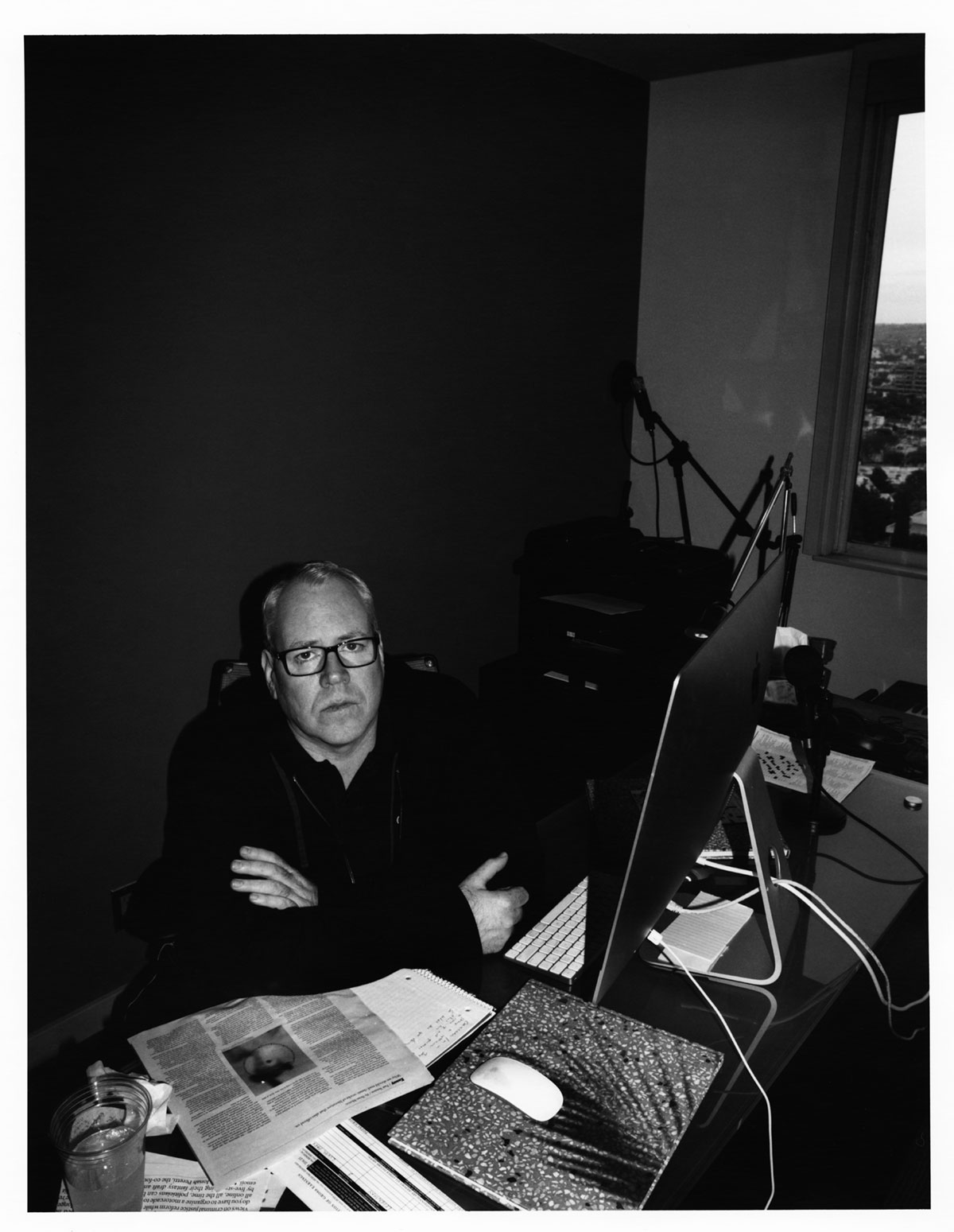

“Anxiety and neediness became the defining aspects of Generation Wuss,” Bret Easton Ellis writes, “and when the world didn’t offer any financial cushion then you had to rely on your social media presence: maintaining it, keeping the brand in play, striving to be liked, to be liked, to be liked, an actor.” If one thing is clear, it’s that the 55-year-old, Los Angeles-born, bred, and based author has not made a career out of “striving to be liked, to be liked, to be liked.” You don’t even have to be an expert on his horror story of Wall Street capitalism, the 1991 novel American Psycho, to come to that realization. You simply have to have followed Ellis on Twitter or have tuned into his podcast (which he started in 2013) to understand that the novelist and commentator tends to prefer walking against the prevailing winds. He served up his opinions bluntly, unapologetically, and seemingly with little regard for the ethical hysteria they are bound to induce on social media for the next twenty-four hours. This April, Ellis has gathered up his deep unease with America at present in a collection of essays called White (the original working title was White Privileged Male). Here, his venom is reserved not only for the soft-skinned millennials who make up Generation Wuss. He also ruminates on liberal Hollywood’s “fake-woke corporate culture,” on the psychosis of self-victimization, on the asexualizing of gay men to fit mainstream tastes, on the death of art in the name of pluralism, on the “warped authoritarian moral superiority movement” that passes for progressive liberalism in the era of Trump, and on why King Cobra is a more interesting film than Moonlight (Ellis does shrewdly speculate that Moonlight never would have won an Oscar if the main character got a blow job on the beach instead of a prudish hand job).

Ellis is a massive fan of Joan Didion—particularly her iconic essay collection The White Album (similarity in title to White intentional)—but, as an essayist, he has much more in common with that other famous 20th-century literary contrarian Gore Vidal, who also spoke his version of sense and reason against the grain of popular opinion. (And like Ellis, Vidal not only had a predilection for critiquing culture through its reflection in the movies, but could often be written off as a bullying, over-privileged grump.) His latest book probably won’t win many fans among the anti–Donald Trump, LGBTQI, #MeToo, or Black Lives Matter movements. But no matter where you stand on the political spectrum or how wrong-headed you feel he can be in some of his opinions, Ellis does make some searing points about how the national obsession with being liked at all costs and the silencing of opposing voices under the banner of inclusivity can create its own American hellscape. The true scourge for Ellis is censorship. This past February, the director Eli Roth stopped by Ellis’s apartment in a high-rise in West Hollywood. The following interview has been condensed from a much longer conversation between the two friends. They began their talk by discussing the merits of Nicolas Roeg’s 1970 cult film, Performance, which is where this interview picks up. —CHRISTOPHER BOLLEN

———

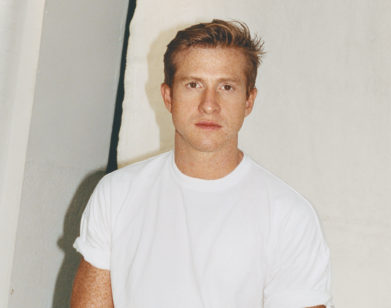

ELI ROTH: Like so many of my favorite films that were attacked when they first came out—Performance, The Wicker Man, The Shining—it just goes to show that time is the only critic that matters. Both you and I have put out extremely controversial work. And your new book really resonated with me. First, you capture the sky-is-falling doom and gloom of post-Trump Hollywood and this posturing that if you’re not acting like you’re going to jump out a window and burn down the city, you are against the revolution. I’ve never seen anything like it. If you’re not constantly publicly demonstrating, people look at you like you’re against them.

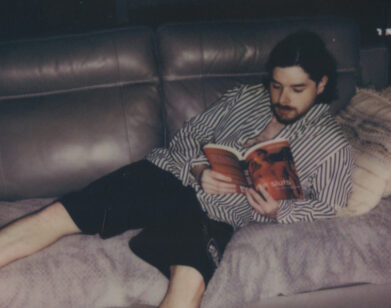

BRET EASTON ELLIS: Or the idea that if there is nothing against Trump on someone’s social media page, they must be a colluder, and therefore they must be part of the anti-resistance. We’ve really entered into a kind of liberal nihilism in the last few years that I’ve never seen before in my life. And, for the record, I have always seen myself as a liberal and as a bit of a progressive. I never saw myself as a Republican. I never even saw myself as all that conservative. But somehow, in the last three years, the times have switched so radically. Living with a millennial communist [Ellis’s boyfriend, the musician Todd Michael Schultz] has really forced me, whether I wanted to go there or not, to be in this centrist place where, since I’m not so totally against Trump, I am somehow a supporter of his.

ROTH: If you’re not publicly demonstrating and liking and reposting certain posts, people are like, “What’s wrong with you?” It’s become this version of guilt by suspicion. I remember reading about the McCarthy hearings and all the pressure there was to testify. You think, “God, that must have been crazy. Thank God we’ve moved beyond that.” But you look at right now, and that’s what’s happening. It’s something in human nature. In a strange way, we feel that Trump has become the final boss of a video game that nobody can kill. No one can get rid of him. He’s beaten the narrative. Now, there is this interesting storm that’s happening where people are digging through tweets from 2008, and something that someone wrote ten years ago now goes on the record as an official statement that defines their personality. But we as adults know this isn’t how people are. Everyone says and does stupid things, and they can change and can grow.

ELLIS: But I don’t think those dumb tweets from a decade ago were even stupid or mistakes. Twitter was used that way when it first began. You made dirty jokes. You said outrageous things. You got people riled up. It was fun.

ROTH: It was the early version of trolling. You were pushing people’s buttons.

ELLIS: Trolling was really the reason that so many people were drawn to Twitter in the first place. But the other thing that’s happening is, on one side of the aisle there is this refusal to accept reality. I see this with many friends who are angry about Trump. Even living with Todd, who is vehemently anti-Trump and passionately pro–prison reform. So Trump gets a prison-reform bill through. My boyfriend doesn’t care, there’s still something wrong with it because it came from Trump. The problem with the resistance in Trump is that Trump doesn’t care about the resistance. That’s why he’s flourished for the last three years.

ROTH: Do you think there’s this feeling that if they can’t get Trump, their frustration is getting channeled in all of these other places? Like, “Bret said something negative about Black Panther! Let’s get him.” It’s like, if anyone says anything in Hollywood, “Let’s get them. Let’s throw them out. Let’s throw them under the bridge if they’re not following the party line.” There’s this kind of feeling of, “Let’s go after anybody we can get, because we lost the election and we don’t know how to take it because we’re so used to winning.”

ELLIS: This Trump Derangement Syndrome that we’re talking about is also, I think, tied to everything that’s been happening in the last three or four years, including the puritanism that you see coming back in vogue. I don’t believe, for example, that #MeToo would have occurred without Trump winning. I think the two are directly involved. I certainly don’t think #MeToo would have been around if Hillary [Clinton] had won the White House. There was something about the idea of having to go after establishment white men, and somehow Trump’s victory activated this. They started with Hollywood because it was the easiest place to find this kind of misbehavior.

ROTH: I think one of the most salient points in your book is that Hollywood is so focused right now on presenting itself as this mecca of inclusion. They’re saying, “We include everyone! Except if you think differently politically than us. We include everyone! Except Republicans. We don’t include them. We include everybody with our political ideology.” You’re the first person I’ve heard that has called out that hypocrisy.

ELLIS: And it’s not even like, “I don’t want to hear it.” It’s not about not liking what Trump has said. People in Hollywood are promoting acts of violence against him. This peace-loving, all-inclusive, progressive—

ROTH: Off with his head!

ELLIS: Right. It’s Snoop Dogg blowing his head off, Kathy Griffin holding up his bloody head, Johnny Depp saying it would be okay to assassinate him, Peter Fonda saying that we should put Barron Trump in a cage full of pedophiles. The list goes on. I mean, this from Hollywood right now! They have just lost their collective mind over him. I don’t know what Hollywood is going to do if he wins another term. I remember the day after the election, my agency, UTA, sent out a mass e-mail that read something like, “It’s okay. We have people on site to talk to you. You don’t have to come to work today. We understand.” Are you kidding me? This is life. You win some, you lose some.

ROTH: The idea that every child has to get a trophy, that there are no winners and losers, has now infected the adults. Have we so lost touch? I remember when I was a kid, it was like first place got a trophy, and second place got a ribbon. Third place was an ice cream. Otherwise, too bad. Try harder, get better.

ELLIS: We didn’t even get a ribbon or ice cream. Someone got first prize and that was it. And that was the way it worked. The thing is, hero and victim are often the same to millennials, and that’s a huge narrative that’s been pushed in the last decade.

ROTH: Definitely.

ELLIS: But even my boyfriend has his limits in terms of political correctness. Even he, who is a hardcore socialist millennial who believes in peace and love and utopian visions of socialism, even he at times has gotten annoyed with his party and with what’s happening. And it goes back to the level of bias in the mainstream reporting. Everyone who followed the election in The New York Times starting in 2015 could see it. That bias was really shocking to me.

ROTH: I always assumed that mainstream news was the news. But what I started realizing was that the news was trying to influence the election to such a degree by tricking everyone into thinking that Hillary had it in the bag. It was almost like the Trump supporters shouldn’t even bother. She was going to win this. And I remember my friends who were on 4chan saying, “No, they’re lying. The Trump supporters are coming out in force and this is going to be a slaughter. She’s going to get destroyed.” I remember thinking, “But if that’s true, how come none of the media is reporting it?” And then we saw the results and people were freaking out. Maybe if there were more realistic polls… I don’t even want to use the word honest, I just want to be more realistic. Maybe if there had been more realistic journalism about what was actually happening, people might not have been so blindsided by the election.

ELLIS: If the media had reported on the entire election with neutrality, I’m not sure Trump would have won.

ROTH: I want to ask you about social media. I’ve stopped engaging in it because there’s sort of no point. I want to go back to the ’80s when you only shared your opinion with your friends. You didn’t broadcast everything you said to the planet. That’s really where I’m at with it now. I used to make a big deal out of Twitter, a big deal out of doing press, thinking I had to put my personality out there like Hitchcock or Tarantino did. I wanted to be one of those directors. And I’ve gone so far to the other end of the spectrum. I look at the Tom Brady approach: Just do your job.

ELLIS: The problem is that even if you tweet something benign now, as I did when I said, “I like Green Book,” there were nasty tweets at me that I was supporting a racist movie about a white savior. Okay, well what do I do with that? What do I do when I post the podcast that’s two hours and 50 minutes long, and 30 seconds is devoted to why I think Black Panther is not that great of a Marvel movie?

ROTH: But that’s your opinion.

ELLIS: And this is what it comes down to: an opinion. An opinion can be something that people try to decimate you over. Everyone is screaming louder than they ever have because they need to have their voices heard over the din of so much other screaming. And I really don’t know how much people really believe or take to heart the positions they have. It often seems like empty caterwauling into the void. Eli, you say you’ve stopped engaging to focus on your creative work. But the problem is that you are a human being. You are an individual. You are also well-known. You are going to be interviewed. Do you play by the rules of the cultural tenor, even if you don’t believe in it? Do you want to sleep at night? This is the question. I guess everyone finds the line they can navigate. But I think there is a problem with censoring yourself, and there’s a lot of self-censoring going on, even in terms of people censoring their own art. I was reading about Lady Gaga who virtue-signaled herself into a big storm of self-congratulatory rhetoric when she pulled her R. Kelly song off Spotify. I was thinking, “What does this do? Does this erase what happened? Or is this just virtue-signaling and this is where we are going as artists?” It’s sort of like you removing the violent scenes from Death Wish because they offend people.

ROTH: The game has changed. And I think we are in overcorrection mode. What’s happened is that press isn’t fun anymore. It’s not loose anymore.

ELLIS: I remember these great, freewheeling profiles of movie stars in the ’70s and ’80s that were certainly not puff pieces of neutered, manicured comrades who are just speaking the Hollywood line. I do miss that. I don’t know what the point is in even reading a profile of an actor now. I don’t know what anyone would get out of it except a lot of anti-Trump platitudes. It’s really, really dull. But that’s what happens in the corporate culture. And that’s what’s happening now, I think, with personalities trying to express themselves. Which is sort of why YouTube is so interesting. I guess you can de-platform people, which is what’s been going on. They’ve been trying to do that with PewDiePie and various other young guys who are just saying, “Fuck you, we’re expressing ourselves how we are. We don’t understand your old-ass game plan about, ‘I can’t say that, I can’t make this video, whatever.’” Or God forbid when Logan Paul says he’s going to go gay for a month. The LGBTQ community went ballistic over that. I’m just thinking, “Really, dudes?”

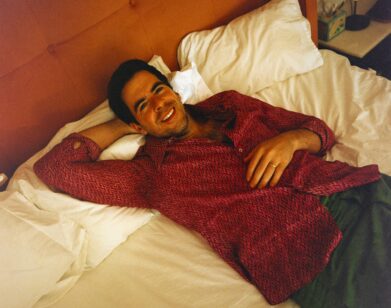

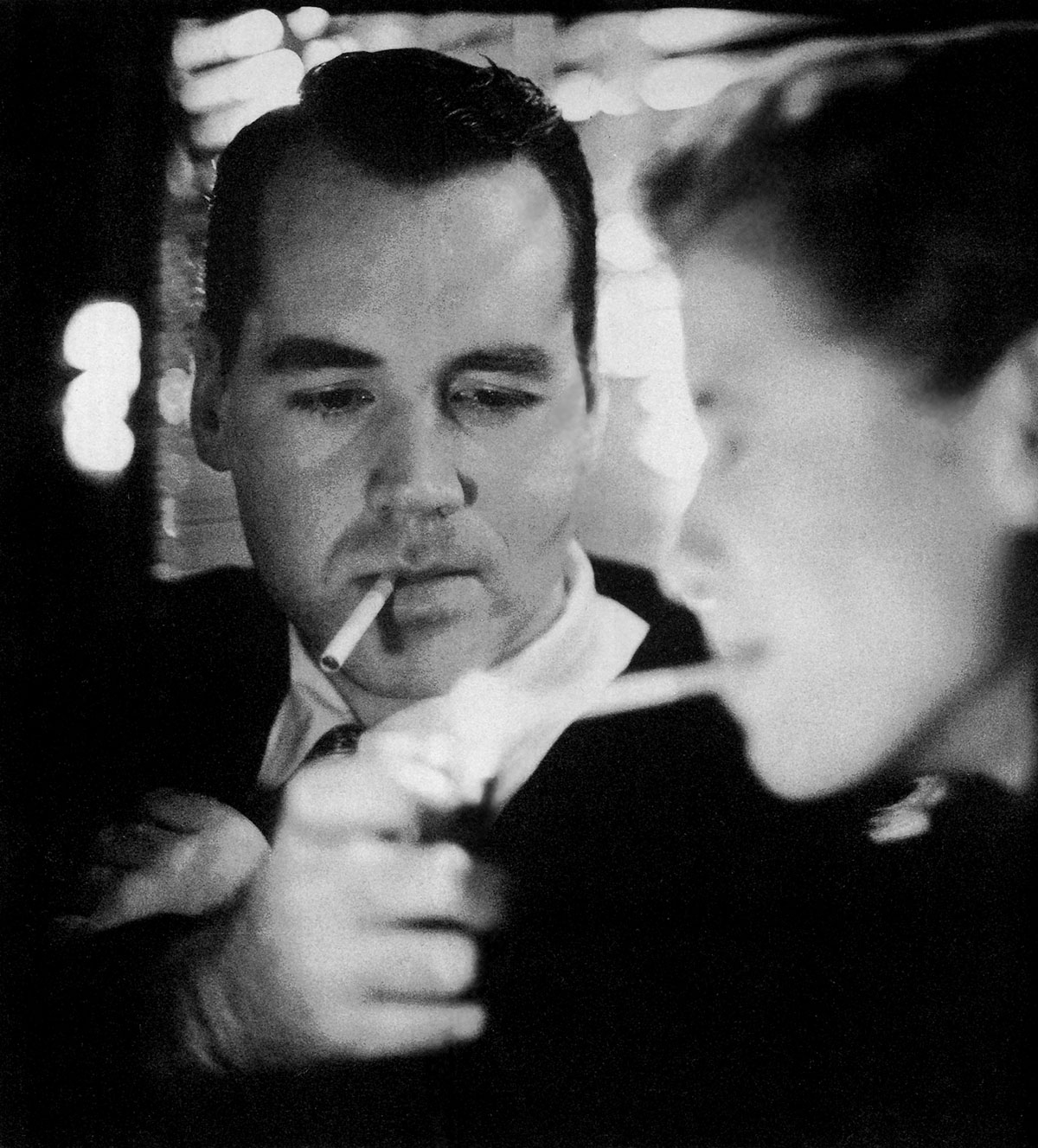

A party photo of Ellis by Andrew Brucker, published in the October 1987 issue of “Interview” on the occasion of Ellis’s second novel, “The Rules of Attraction.”

ROTH: One of the things you write about in your book is this idea of two Brets—the private Bret and the public Bret. That started happening to you in the ’80s with your success at a young age. But I feel like everyone has two personalities now. They have their social media profile and they have their real life, and they try to line up the two all the time. It’s like people are constantly managing a personality. Don’t you think everybody has a double life now?

ELLIS: The double life I’m talking about in White is the self that is created by an audience and media. I grew up in L.A. I was very used to the media. The notion was that the only way to deal with the media was to not care about it and just try to be yourself. That was a long time ago. When I started to become a well-known person in the mid ’80s, I tried to be as real as possible. But what I saw happening was that this brand was being created that I had no control over. It was created by the media who wanted to see me as this dark prince. It was just a litany of stuff about me that wasn’t necessarily true. A slant. It did give me some stress and anxiety because it was out of my control. It wasn’t that I really cared so much what they said about me. I’ve never really cared about what people say about me. It was the notion that another person had formed and taken over the name of Bret. And it’s still there. I see that person named Bret referenced all the time.

ROTH: I see it, too, with myself. I was always fascinated by frat characters and the asinine behavior of guys in college doing stupid shit. But I never behaved that way. I was a nerd in art school making movies. I just thought that people who do stupid things would make the perfect victims in horror movies. I don’t think I’d be a good victim because I’d call the police. I’d be responsible. I’d lock myself in a room. But I put in these obnoxious frat characters to provoke a great situation where you can have a spectacular kill. And all of a sudden, it’s “Eli Roth, the frat boy.” Suddenly I became the projection of those characters. And it is the same way with you. Bret is Patrick Bateman, just like I’m those guys in Hostel.

ELLIS: There’s a need for people to merge those narratives because it’s easy. I talk about the distinction between artworks and artists in the book. But the thing is, you’re going to be disappointed by who the artist really is. Just enjoy the art, enjoy the movies, enjoy the books, enjoy the records, because you’re going to find out that the artist isn’t someone you necessarily want to hang out with. That first year of becoming famous is fantastic. It’s really fun. It’s really exciting. Everyone’s asking your opinions. You’re often written about well, and then it’s just that for the rest of your life you have to avoid humiliation.

ROTH: I used to love the controversy and then I realized how much value I was placing on it. I was judging myself based on how controversial I was, what I was doing, and I think even though the response was generally very positive on Hostel 1, for Hostel 2 the knives were out. Suddenly it was that moment where the narrative is beyond your control and there’s nothing you can do about it and everyone just goes, “Well, this is torture porn and you killed girls.” No one was upset about the guys getting killed in Hostel 1. I was interested in the chapter of your book where you were disinvited to the GLAAD Awards.

ELLIS: I was invited and, again, what happened was that someone looked at some old tweets and I had said some fairly outrageous things about other gay men in Hollywood. And I was then asked not to come. But it did seem to me a ridiculous place to be as a gay man. To me, the GLAAD Awards were representing the ideal of a whitewashed corporate gay who wasn’t messy, wasn’t too sexual, wasn’t rude, wasn’t opinionated—that was the only person that they had room for. And I have to say that’s not just GLAAD, that’s the culture today. But, you know, I have always felt that in my work I’m pretty gay at times. Someone once told me that American Psycho was the gayest novel they’ve ever read even though there’s really no gay sex scene. But certainly from Less Than Zero on, I’ve tried to portray gayness with a kind of casualty, a kind of neutrality as just another thing that takes place within the wide-open world. Maybe it’s easier for me growing up a white, privileged gay, and that’s something that I have to grapple with. At the same time, I think it’s just part of my artistic intention and it really doesn’t have a lot to do with growing up upper middle class or growing up white. It has to do with what I’ve been drawn to aesthetically. Presenting people in this way, having this kind of style, having this kind of outlook. It’s not political. Maybe it would have been more political if I had been gay-bashed or had been subjected to certain things that I simply wasn’t subjected to in L.A., or Vermont, or Manhattan. But it also doesn’t mean that I’m not empathic.

ROTH: I grew up in an upper middle class, privileged Jewish community, predominantly white—that’s the culture I knew in and out. And I was always taught to write from a place that I knew. It didn’t mean I wasn’t going to try to expand my horizons or look into another culture, or that my interests didn’t grow. But in those early years, you formulate who you are and what you want. I feel like it’s okay if you write about white people. It doesn’t mean you’re racist. That was your experience and that’s the story you’re telling. It doesn’t mean you’re excluding anyone else. But it does feel like right now there’s this overwhelming resistance to that. People are scared to pick a lane because everybody is so afraid of being seen as racist. They don’t even want to criticize a movie that has people of color in it because they’re terrified they will be seen as racist.

ELLIS: The other thing that’s left movies is the taboo. There used to be a kind of movie that was extremely well made that really pushed buttons. It was dirty, and it was offensive. Certainly Lars von Trier is an example of this kind of bad-boy director. The provocateurs, that’s what I feel is missing. Maybe you see it apologetically in raunchy R-rated studio comedy, but even then, not really. I keep thinking that Animal House would be about 24 minutes long if it was released into our world. Some of the funniest scenes in it are just so politically incorrect that you couldn’t do it.

ROTH: You really couldn’t make that movie now. But also those movies are very much commenting, humorously, on their time. You know, it’s interesting when people look back at movies and go, “That’s not funny. How could people have thought that was funny?” It was brilliant to set Blazing Saddles in 1874 because it allows you to really comment on 1970s racism. I think Jordan Peele cracked it in Get Out when the white guy says, “I wish I would have voted for Obama for a third term.” And then they turn out to be the worst people ever. Peele was able to make a movie that talked about race in a way that we all could discuss it. But who knows what it will be like looking back on that movie in 30 years. I’ve had fights with people now who say you can’t enjoy Revenge of the Nerds because it supports rape culture. You look at that now and you sound like a monster for having enjoyed it as a child. And it’s just this idea that we’re all supposed to present these weird, clean versions of ourselves that aren’t real, that aren’t true. I love how you talk in your book about your investment in a movie, about waiting on line and wanting it to be good. That’s when the movie was an art form that was the center of the conversation. Now it’s music, it’s social media, it’s YouTube. There are so many other places that people put their attention. But for our generation, movies were everything.

ELLIS: I feel much more comfortable with novels. The problem is that novels just do not have the kind of platform that even movies have. But I always felt the same way when writing a novel. I wanted the novel to be an event. I wanted it to be an experience. I wanted it to be immersive. I wanted you to fall into it. I didn’t want to write a little novel. There was a lot of criticism, for example, about being dropped into Patrick Bateman’s world: “Where are we? Why are clothes being mentioned, and why is every dish being mentioned? Why am I here? Why am I listening to this stupid conversation that goes on for four pages?” But I wanted the reader to drop into this world and have this completely immersive experience. I always felt that way about all my novels, that I wanted them to be special and not just about the English teacher at a college who’s an alcoholic. I wanted to supply an experience. I also wanted to push some buttons.

ROTH: But do you feel that it’s important to you when expressing yourself to make shockwaves in pop culture?

ELLIS: I remember with Less Than Zero, I thought that book was going to sell no copies. I was just happy it was being published. Then, you see it go out in the world and it has that kind of impact. I don’t know… After that, I never felt that I was going to be able to play the game, and that I just had to write the books I wanted to write. As I write in White about writing American Psycho, I really believed I was working on an experimental novel that my publishing house was going to probably be unhappy with, but not for the reasons that they ultimately were unhappy. I just thought it was so weird, so strange. Then, of course, I spent nine years on Glamorama, and I actually thought, “Oh my God, it’s my magnum opus,” and it really went out into an uncaring world. No one cared about that book. I’ve always been a bit wrong about stuff like that. With White, I wanted to have a kind of narrative. I didn’t want it to be a dry collection of essays where I threw in everything I’ve written the last 20 years. In a way, even if it’s nonfiction, it was kind of a creative thing. The thing is, I’m not sure any of my books would be published now. I don’t even think American Psycho would be allowed on the internet. And that does make me worry about the future. Even within the supposed freedom of the internet, everything is being policed. You have people who are blocked and canceled and censored for the most innocuous shit. So what do you think is ultimately going to happen politically in this country?

ROTH: I think that growth is painful, and we’re in a growth period. People are uncomfortable, and hopefully that discomfort will motivate people to not just get more politically minded, but to realize that someone who thinks differently than you is not a bad person. But I think it’s all driven by money. The people in power, who have so much money, are keeping this fight going. They are enjoying the back-and-forth fighting because it keeps people from focusing on some other things that maybe they should be focusing on in the world, like the ocean, like the fact that we’re killing all the animals on the planet, like the fact that Africa’s being completely raided by other countries. There are so many things that are going on that they don’t want people to focus their energies on, that they’re perfectly happy to keep us engaged in this sort of awkward political civil war. I just think it’s a way of everyone being numbed. If I’m going to complain, it’s going to be with my vote and I’m going to focus on real problems.

ELLIS: Exactly. That’s what I’ve always told everyone who is freaking out. Your vote is going to make the difference. You giving Stormy Daniels the key to the city is not going to do anything. This notion of trying to humiliate Trump is not the way to work. It’s going to work by voting him out.

———

Grooming: John McKay at Frank Reps