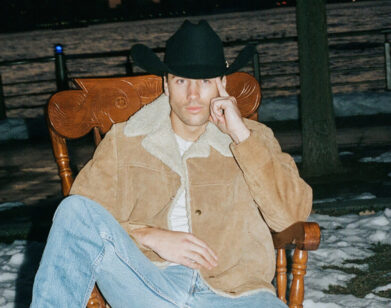

Simon Cowell

Music isn’t about numbers. And people have argued that the success of Simon Cowell’s various ventures-which include his management company Syco, as well as competition TV shows like American Idol and X Factor-isn’t fundamentally about music. And yet the Cowell numbers are there, staggering in their scope: for example, three recent Cowell-shepherded artists-Susan Boyle, Il Divo, and Leona Lewis-have sold a combined 46 million albums between them. While the record industry at large has been struggling to adjust en masse to diminishing record sales, Cowell has established himself as just about the only man who can still reliably move “units”-even if they’re digital now-on that scale.

The 51-year-old English-born Cowell, who was known for his acerbic attitude towards contestants during his time on Idol, often talks about the importance of loving music when dressing down would-be stars. And while he isn’t a singer or songwriter himself, he has spent more than 30 years in the music industry, working his way up from an entry-level job at EMI. Along the way, he helped launch the career of Westlife, one of the U.K.’s biggest-selling boy bands. But Cowell didn’t become a household name in America until he began appearing as a judge on Idol, where he remained for nine seasons, before jumping ship to start his own version of a music competition show, The X Factor, which debuts on Fox this fall.

While notoriously sharp-tongued on air, when Cowell spoke with us from Los Angeles, where he now lives, he was charming, self-deprecating, and easy-going— in short, anything but the bristly curmudgeon he plays on TV.

DIMITRI EHRLICH: What’s the most rewarding aspect about your daily job?

SIMON COWELL: When it’s going well, it’s probably the best job in the world. I used to love watching TV as a kid, and I’ve always loved music, so when you’re in a position where you’re working on two things you like, you don’t get that awful Sunday-evening feeling I used to get when I was at school round about 7:30 at night, where I used to feel sick at the thought of waking up on a Monday morning.

EHRLICH: Do you ever feel bad when you have to tell someone that they’re terrible?

COWELL: You know, it’s case by case. In the main, no, otherwise I couldn’t do this. I was recently talking to somebody very well-known about doing the job, and she said, “I don’t want to say no to anyone.” And I said, “Well, then you’ve got a problem.” Unfortunately, this job does entail a few nos. There are people who come on and you like them within seconds, and you want to

give them good news, and then there are other people who come out and they tell you that they’ve been blessed and this is their destiny, and they’ve never worked a day in their life, and they think it’s all going to happen. I must have met tons like that. I don’t feel bad.

EHRLICH: Yeah. That terrible J-word: The journey.

COWELL: Ugh. Do you know what? It’s so banned, that word now, that even when I’m on a journey, I won’t say I’m on a journey.

EHRLICH: Call it an adventure.

COWELL: A trip. It’s a trip.

EHRLICH: What is the X factor, if you had to boil it down to one quality?

COWELL: Well, luckily, it’s indefinable. Having the audience behind you on the auditions helps you. But it flits in and out of time. I mean, Lady Gaga right now obviously has it. I have a feeling if Lady Gaga would have walked in six years ago on American Idol, maybe with a lobster on her head, she would have been told, “No.” It’s normally somebody who’s smart, gets the market, and understands all the ethics, which are hard work, charisma, being original, and being memorable. I mean, Ziggy Stardust, David Bowie at that point, when he reinvented himself—his career could have gone in a very different direction. Or Elton John. I mean, those are two people who’ve got it, because they understand entertaining, they under- stand the audience, and they’re smart.

EHRLICH: And they also both endured a lot of nos, took a lot of rejection.

COWELL: I do see a big difference in the American work ethic compared to the British work ethic in a lot of artists. Nicole Scherzinger, who is a judge on X Factor, is a great example of that. This girl, honest to god, is like a machine. She’s up at five in the morning. She’s in the gym. She’s jogging. She’s working. She’s thinking about everything. She’s rehearsing. She’s hustling. She’s aware of what’s happening around her. She’s got that 360-degree vision. Beyoncé has that as well. And I think what we’re experiencing is almost like one of those B-movies from years ago where we’re seeing sort of the rise of the super female pop star. It’s like a different breed.

EHRLICH: The fembots are coming.

COWELL: Yes! Exactly. It’s like they’ve all been bred to sort of take over the world and dominate everything in entertainment. They are unbelievable, these girls. Hopefully that’s going to rub off on what we’re doing on this show, because there’s a lot of people who think they can just wake up at 11:00 A.M., walk into a recording studio, go into the audition room unprepared, and people are going to get them. And also something else that’s important, which I really discovered this year, is taste. You really become aware of how bad a lot of people’s tastes are. They just get it wrong and don’t understand what fits, what makes it work.

EHRLICH: I guess it’s also the instinct for leading the audience. You can’t be too far ahead—the masses don’t want to be totally shocked, but there’s a thin line between being boring and then being too far-out.

COWELL: I would agree with that. And I always say that you’ve got to be very aware that, particularly at my age, if you’ve got kids of 14, 15, 18 watching the show, that you can’t talk down to them. You’ve got to be confident enough to let their voices be heard and not be afraid to do something that’s unpredictable.

EHRLICH: What’s the key difference for you between the way you feel doing The X Factor versus how you felt on Idol?

I HAVE A FEELING IF LADY GAGA WOULD HAVE WALKED IN SIX YEARS AGO ON AMERICAN IDOL, MAYBE WITH A LOBSTER ON HER HEAD, SHE WOULD HAVE BEEN TOLD, “NO.”Simon Cowell

COWELL: I’d have to say unpredictability. We got to a point, if I’m being honest with you, particularly after nine years, that when I was sitting in the audition rooms, it was like Groundhog Day [1993] after a while. I just couldn’t bear the boredom of it.

EHRLICH: What’s made you laugh the hardest while working on these shows?

COWELL: Anything I shouldn’t laugh at makes me laugh. I mean, I’m bad at that, when somebody is singing something terribly and I’m thinking to myself, “If I laugh now, this is the absolute worst thing I could ever do,” and then I start laughing and I can’t stop. It’s like being in church. You’re pinching yourself, you’re thinking of anything terrible to stop yourself, and you can’t.

EHRLICH: You say The X Factor has helped to sell over 90 number-one singles and albums and 150 top-ten records, so now when you meet the heads of major record labels, what’s their attitude towards you? Is it gratitude or jealousy or fear or what?

COWELL: [laughs] Well, you know what the music business is like. They’re not the friendliest bunch of people in the world. They’d all stab you in the back given a chance. I’ve always believed in healthy competition. There was an astonishing letter years ago written by the head of EMI, and the arrogance and the con- descending way he was talking about what we were doing. This is not what you’d call everyone’s cup of tea, but you can’t ignore the fact that it does sell records.

EHRLICH: The Hollywood Reporter called you the most powerful person in reality TV, and Time magazine included you on their list of most influential people in the world. You know you’ve obviously had tremendous financial success. Are you happier now than when you were a teenager?

COWELL: Oh, I think it’s crazy even believing half of this stuff. It’s hard to say that anyone is the most influential person or powerful, because I don’t know what that means any more. I’ve got an ability to get funding for things, and I’d say that’s probably about it. After that, I’ve got to do what everybody else does. The demise of a lot of people has been when they believe all that rubbish—that they’ve got power, that they’ve got influence. The only people with power today are the audience. And that is increasing with Twitter, Facebook, and everything else. We cater to their likes and dislikes, and you ignore that at your peril. If I had to say who is the number-one most powerful figure is in reality TV, it’s very easy. It is the general public. They’re the only people who have power now.

EHRLICH: The day that you learned that Westlife, a group you managed, were about to get their first number-one single was the day that your father passed away, and it was probably the moment when you recognized that all the millions of dollars in the world cannot insulate us from intense misery. So my question is, how has your thinking about wealth shifted over the years in relationship to seeking happiness?

COWELL: It’s a very good question, Dimitri. I don’t really know the answer, other than I think success, or lack of success, doesn’t really influence who you are. I think if you’re an unhappy person, you’re always going to be an unhappy person. You’re probably going to be less unhappy if your business is doing well, if I’m being honest. I tend to judge my moods mainly now on whether I’m happy with the work we’ve produced. It’s not so much the scale of the success, but the quality of the work. That’s what makes me happy—if I think that we’ve done a good job, we’ve found a great artist in the auditions, or we’ve made a great record. I still get a big buzz out of that.

EHRLICH: I know your dad was in the music industry. He worked for EMI. What did you learn from him about music and about life?

COWELL: My dad did teach me a very important lesson about people when he explained to me that everybody around you will have an invisible sign on their head, which says, “Make me feel important.” And I still remember that on a daily basis, that when you work with a big team of people that you’ve got to understand and recognize that everybody there is helping you do what you want to do. And you’ve got to be aware of that my name on my shows. I don’t need the credit.

EHRLICH: You got a degree in sociology—does that come in handy at all in your current work in terms of understanding social behavior?

COWELL: I’d love to say it was a degree, but it was what we call an O-level. It was a written examination. But I was interested, and am interested, in people, and you can’t do this job if you don’t get people.

EHRLICH: One of your first jobs out of school was as a production assistant on Stanley Kubrick’s film The Shining [1980]. Do you ever run into Jack Nich- olson these days and remind him that you got him a cappuccino?

COWELL: I was actually worse than a production assistant. I was literally, if you go down to the bottom of the credits, it’s called a runner. I was offered the PA job eventually but didn’t take it. I took a job in the mail room at EMI Music Publishing, and that was kind of a pivotal moment where, at 16, I made a choice whether to go into the film business or the music business, and I decided on the music business.

EHRLICH: And it’s sort of worked out okay so far.

COWELL: Yeah, it was the right decision.

EHRLICH: In 1989, your record label, Fanfare, folded, and you wound up in debt and, for some time, had to move back in with your parents, at the age of 30. Obviously that must have been humbling, but what was the positive side of that setback for you?

COWELL: Well, it was a wake-up call, really, because this was all off the back of what was happening in the ’80s, where things had got really excessive. I was living way beyond my means. So when I lost a lot, and I moved back in with my parents, it was quite a relief in a weird way to get rid of all these possessions that I didn’t really own.

EHRLICH: Do you have any misgivings about being characterized as the guy who is blunt in his criticism, which sometimes includes even contestants’ physi- cal appearances? Or has that become almost like a branding element for you where it would be weird for you to come out and be like, “Hey, that’s fantastic, I love it!” Do you feel sort of boxed in, or is it actually an honest reflection of who you are?

COWELL: It’s a bit of both. You know, when you look at a picture of yourself when you were 17, and at the time you thought you were the coolest kid on the block, and now you look at it and go, “Christ, what was I wearing?” I think I’ve probably gone through that in the last ten years, and probably in a much more exposed way. I mean, literally down to what I wear. At the time, you thought you were being funny or it was the first thing that came into your head, but you’re always going to have those regrets. At the same time, when we’ve made these shows we’ve tried to show both the positive and the negative parts of what we do. That does mean at times when I watch it back, it’s like watching a horror movie. You’ve kind of got a pillow over your face. But that’s what happened on the day, and you have to just deal with it, I guess.

EHRLICH: What effect has all this success had on your overall life ambition? Has the general target shifted at all?

COWELL: If you had met me at 30, we would have been having a very different conversation. At 20, you’re cocky and you think you can rule the world, and you get it all wrong. At 30, I was probably getting quite nervous and understanding that this is a ruthless business, and if you didn’t have some kind of control over your destiny, you may have a problem. And I suppose that’s the best thing that I have now. I feel that I have a control of my life. Even though the public is still going to ultimately decide what’s going to happen, at least you can make the decisions yourself. You haven’t got to ask lots of people what they think. And you can have the opportunity to make and do what you want to do.

Dimitri Ehrlich is a contributing music editor for Interview who has written songs for Moby, Kim Wilde, and American Idol star Pia Toscano.