IN CONVERSATION

Alex Ross Perry Tells Jonas Åkerlund Why His New Pavement Doc Is Slanted and Enchanted

Photos courtesy of Alex Ross Perry.

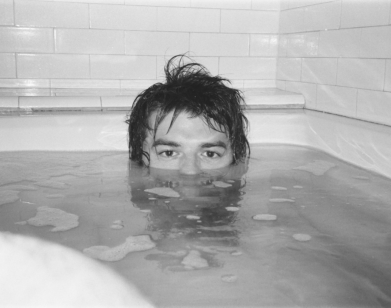

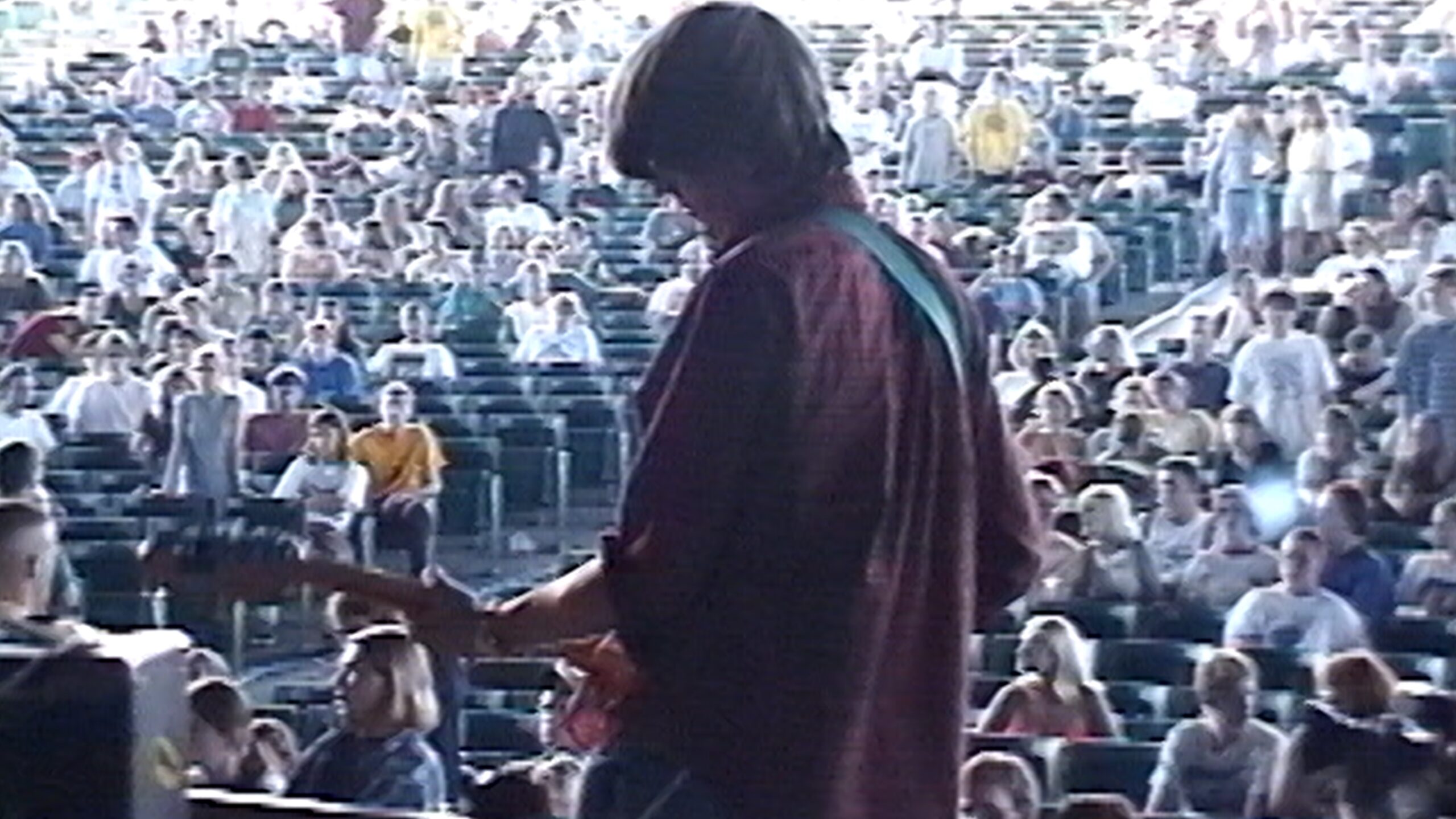

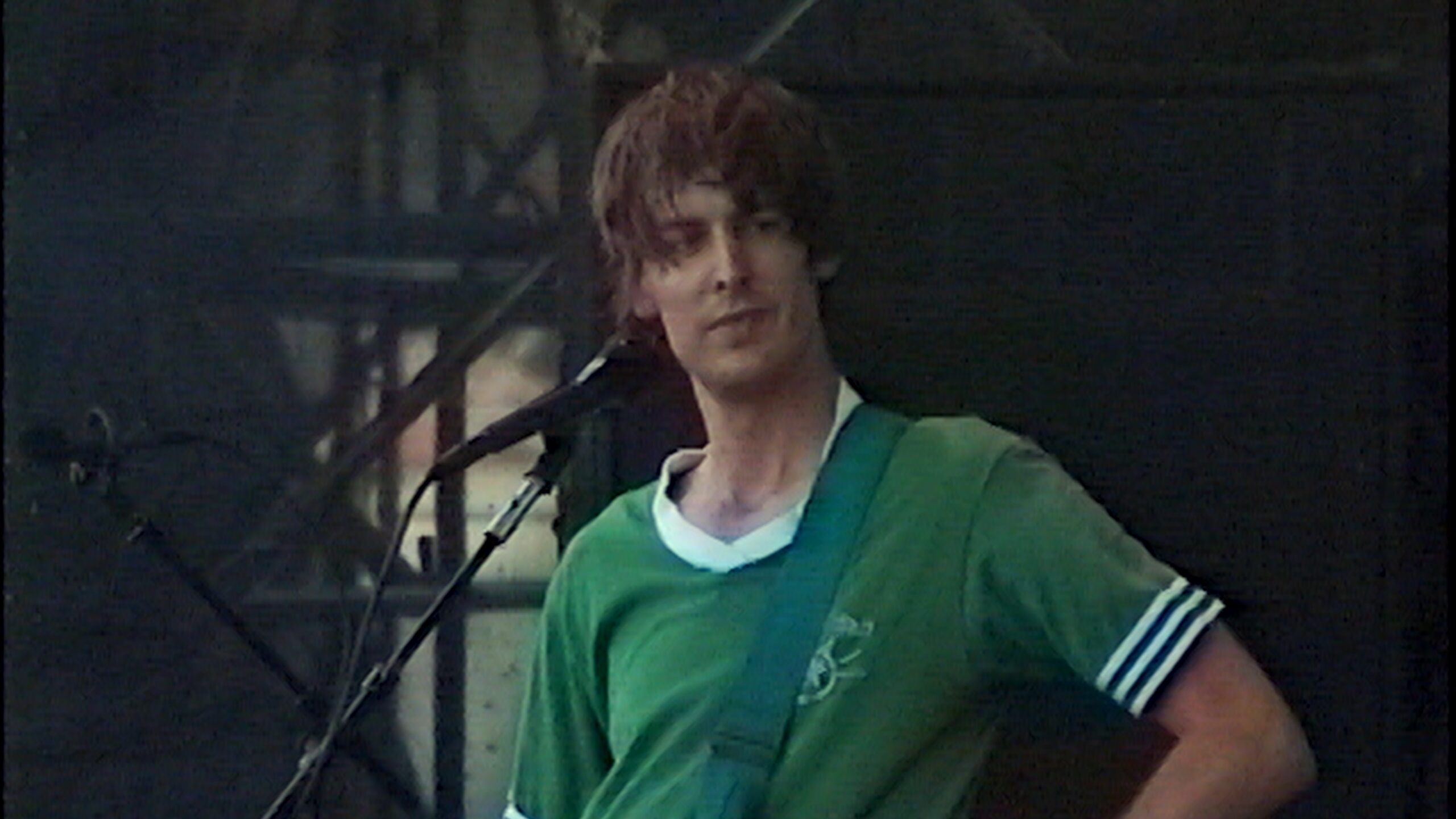

In an age where music documentaries often double as savvy bits of marketing, the filmmaker Alex Ross Perry went against the grain. His new movie Pavements blurs the lines between fact and fiction, following Pavement as they emerged as one of the defining bands of the 90s, interspersing archival footage with scripted scenes where the band members are played by actors. “All we want is to make something that feels like it’s from an era where the whole project wasn’t managed by whoever owns the publishing,” he told director Jonas Åkerlund, who knows a thing or two about working with subversive artists, having directed music videos for Madonna, Metallica, and Lady Gaga, to name a few. More than willing to forgo another sterile and manicured documentary was the band’s iconic frontman Stephen Malkmus, one of the architects of Gen X slacker rock, who’s played by Stranger Things Joe Keery in the film. Through a continuously splitting-screen, Perry weaves fictionalized accounts with real interviews to tell a story of delayed notoriety and unanticipated pitfalls. In conversation, Perry and Åkerlund explore the impact of fandom on documentary filmmaking and the agony of the festival circuit.

———

JONAS ÅKERLUND: Hey, man.

ALEX ROSS PERRY: How are you?

ÅKERLUND: I’m pretty good. How are you?

PERRY: Good. Thank you for doing this and doing it within a few days of asking. I appreciate it very much.

ÅKERLUND: It was good timing. I’m on my way to travel this weekend, so it was good that we could do it now.

PERRY: What are you doing in London?

ÅKERLUND: I’m doing a mix on my Metallica film, a theater mix for the Tribeca screening. Then I also made this dance film with Damien Jalet that we’re going to screen at SXSW London.

PERRY: Neat. Then you’re coming here?

ÅKERLUND: Then I’m coming there. I have two films. It sounds like I’m like, a festival guy. I never go to festivals, this is really rare for me.

PERRY: Well, I guess it’s a big part of the marketing push these days.

ÅKERLUND: I guess so, but I was never a film enthusiast in that way. I never really attended film festivals. But it’s fun and it’s a big ego boost when you do it. In this case I am super proud of my film.

PERRY: How long has the Billy Idol one been in the works? I didn’t even know that you were working on it.

ÅKERLUND: These fucking documentaries, they start as such a great idea and then you work on them forever. So the Billy one is five years, and the Metallica one is close to three years.

PERRY: Yeah. I mean, Pavements was four, from starting it to premiering it. I’d never done anything for that long.

ÅKERLUND: Yeah. I’m curious about your film. Was it your idea? How did it get to you?

PERRY: One of the producers, Danny Gabai, came to me and said, “They’re looking for a filmmaker who could come up with a compelling, unique, non-traditional take and I thought of you.” And we just took it from there. I remember you saying to me that so few bands want to do anything different now. It’s become so flat and uninteresting. Now it’s all about making a valuable piece of marketing. That made me feel really encouraged at that time. All we want is to make something that feels like it’s from an era where the whole project wasn’t managed by whoever owns the publishing or the band’s management.

ÅKERLUND: Right. Especially in documentaries, a big part of the job is how brave the artist is to say “yes” to stuff. It’s easier to not have the courage to go all the way.

PERRY: How have you seen that change?

ÅKERLUND: I’m spoiled, as are you, that we actually met artists who want to do cool stuff and have integrity and confidence to do so. Madonna has always been my biggest inspiration when I work. She was the one who taught me to always ask questions and never do what’s been done before. All the Ghost stuff you do is great because Tobias [Forge] really wants to make cool stuff, and that makes our job easier.

PERRY: Yeah. It’s inspirational to me, in the couple of years that I’ve orbited the Ghost creative family as a fan. He’s not making this clean piece of promotional content. He doesn’t want any of that. But doing Rite Here Rite Now and then the Pavement movie, it’s fun to be playing in two different sandboxes, making two very different kinds of movies.

ÅKERLUND: Are you a Pavement fan?

PERRY: Not as much of a fan as I was of Metallica, but a fan for sure. That didn’t mean that I had every album and obsessively tracked every piece of information about them. My perspective as the filmmaker wasn’t, “This is my favorite band and this is the best band in the world.” They are the editor’s favorite band though, and that tension for us was valuable because I’m saying “I want to make a good movie that grapples with a lot of this and isn’t fan service.” He’s like, “You made that movie. Now I have to edit it from the perspective of, ‘They are my favorite band.'”

ÅKERLUND: Right.

PERRY: Do you ever feel like you’re at the mercy of the story being, “Isn’t this amazing?” Versus, “I want to tell something that gets at something deeper?”

ÅKERLUND: It depends on what it is. I don’t necessarily think it’s an advantage to be a big fan. For some reason, especially in music videos, I was very snobbish the first few years that I worked where I only did things I personally liked. Once I started to step outside my comfort zone, I did better work. With these documentaries, you live and breathe it for so long, you really have to care about it. That’s what I love about this Metallica film. It’s a really rewarding feeling to watch this film and see that people are actually touched by it.

PERRY: How much is that in mind when you’re conceiving of shooting or editing? For Pavements, I was always trying to not think about the fans because that’s your worst audience. The diehards who love the band in a specific way and want to tell you, “Here’s what you got wrong.”

ÅKERLUND: Absolutely. You just have to ignore it. I’ve done a couple of movies and series based on true stories and it doesn’t matter how much you try, somebody’s going to be pissed off or find something wrong.

PERRY: Part of what I found while working on these movies is that a band like Pavement have this highly idiosyncratic, specific fan base who have for 30 years been creating this identity of the artist that isn’t how the artist even sees themselves. I always think about what I like to watch as someone who is a junkie for these films and the way that they get told. I’ll watch things that I think are going to not be good, but when something is good it’s a bonus.

ÅKERLUND: Right. I guess with documentaries, the goal is always to span beyond the fans and actually reach people. I mean the only way to do that is good filmmaking. Some Kind of Monster reached a huge audience, way beyond the fan base, because it was a movie that made you feel.

PERRY: With Pavements, the goal was to do fiction and non-fiction in one movie. I know you’ve worked extensively in both, so how do you find that difference and is that scale sliding depending on the project?

ÅKERLUND: I don’t know, I never crossed over like you have. I always wanted to. Spinal Tap is one of my favorite movies of all time and I actually bought into it. I couldn’t believe I didn’t know about this band, which was promoted as a documentary. I went to the movie theater and I bought into it for the first 10 minutes. I was like, “How can I not have heard of this band?” I remember I pitched to Marilyn Manson early that we should do his life story and completely make it all up. Everybody came up with stories around him anyway, so let’s ride that train. I love that idea.

PERRY: Are you saying to artists, “I would like to do this,” or are they saying “We are looking for someone, what would your take be?”

ÅKERLUND: They come about in different ways. It’s not like I’ve done a ton of documentaries either, but they always come out of some personal relationship. I actually read Billy [Idol’s] book, which I thought was cool. He was in the right place at the right time and he made all these great songs that everybody knows. He originally wanted to make a movie about his life. We talked about it and decided to do a documentary first and see how that works. We followed his book, his story, and he had enough stories to make a film interesting. I do have my favorites that I would love to make a documentary with, but I’m also scared of doing it because maybe somebody else should do it that is not as close as I am to it.

PERRY: White whale subjects, you mean?

ÅKERLUND: Yeah. I’m a huge Ozzy [Osborne] and Black Sabbath fan, but I’m careful with it. Working on the Metallica thing didn’t really feel like a documentary in a music doc. It was more about finding these stories and having these people tell this story in front of our cameras. A lot of research, a lot of traveling and shooting a lot. We shot over 200 interviews for it. That’s the “quantity to get quality in the edit” approach.

PERRY: When you told me that idea I was like, “That’s a movie we haven’t seen yet.” I wish I could have heard that idea 10 years ago because it’s a great new concept of honoring that relationship that exists between artists and their most devoted fans. Also, narrativizing it and using that as a way of not having identical interviews of everybody saying, “I feel this way about this artist.” To me that was exciting because there’s nothing that I love more as someone who watches all these things. That would not be Metallica’s first movie. They only have the ground to make that because it is an ongoing project of theirs to always have something going in that world.

ÅKERLUND: There’ll be movies made forever about Metallica.

PERRY: What do you think is the difference between the artists that are at that level and the artists like Pavement where you’re like, “It’s my responsibility to make the one that there’s going to be?” We kept saying things like, “This has to be the definitive movie. If we mess this up, there’s not another one in five years.”

ÅKERLUND: They’re still young, though.

PERRY: Yes, that’s true. Of course, there could be another movie, but for us the hope was there shouldn’t be. The story can go on and it will, but the story as it goes on would only be just about the continuation of what we’ve done. Have you done stuff with people that ended up dying or retiring?

ÅKERLUND: Not really. It’s hard to think of any artist in music that retires because most of them just keep going. I do know artists that are fading away because of their death and because their estate doesn’t want to do anything. We were talking about George Michael the other day, how the new generation doesn’t know them. On the other hand, all the kids know a Queen song.

PERRY: Probably.

ÅKERLUND: Yeah, because they’ve kept their catalog going and George Michael’s family doesn’t want to do anything, and it’s sad because his legacies kind of fade away.

PERRY: Did you follow that story of the eight-hour Prince movie that can’t be released?

ÅKERLUND: Yeah, I heard about that.

PERRY: I’m always interested in the protectiveness or what the piece is meant to be. Is it meant to be a celebration or is it meant to be an exploration? Or is it meant to provoke something within the estate or the artist themselves? Pavement were both gracious in letting me do this, but also hands off in a way that is fairly uncommon these days. Part of that was not caring, but was also their stated desire to not make the thing where the band or the artist is a credited producer. It’s apparent just from watching it that they were looking at cuts and saying, “Take this out, put this in.” At some point our editor said, “We’re not only making this movie for you guys.” That was a very instructive lesson in telling them, “You wanted us to not make two hours of fan service. You have to just step back and acknowledge that that’s going to involve 25 minutes of this that you cringe while watching.”

ÅKERLUND: That’s a challenge for anybody who works with any artist, if it’s scripted or non-scripted. As long as the artist is alive and active, it’s important that they’re proud of it and that they can stand up for it.

PERRY: Yeah. What’s something that you did at some other point that you’re like, “Now, the artist or the label or their management would shut that down, so I’m glad we made it.”

ÅKERLUND: More than 75% of my 200 music videos would not be made today. I’m a hundred percent sure.

PERRY: Because of the budget or because of the freedom?

ÅKERLUND: Budgets with music videos were never great. Even when they were great, the ambition level was always bigger than the budget anyways. When I started with music videos, the brief was always to do something that’s never been done before. Do something where we mess with the audience, break all the rules. Again, I was lucky to work with artists who really stood by that. There’s a lot of creative work out there now, but I’m sure that a lot of my stuff would not get made today.

PERRY: Do you feel optimistic in any way? Do you feel any trepidation about how to keep things moving or be creative or work in the same way or evolve or fear for the younger generation?

ÅKERLUND: I don’t fear for the younger generation, but I do realize that I am so blessed to have one of the greatest creative windows. I was born in ’65. To grow up with the music, art, culture, movies, fashion and everything that I love and then working in America from the mid ’90s onwards, that’s a very unique window that’s probably never going to come back. Being able to work pre-internet and get to learn how to work with the internet is such a unique window. What the future is, I have no idea. When MTV was at its best, every video was news. It reached people all around the world. All my idols that I looked up to when I started, they’re kind of gone. None of them are really working anymore.

PERRY: The director idols or the music idols?

ÅKERLUND: Director idols. Always one foot in fashion. Jean-Paul Gaultier, [Jean-Baptiste] Mondino, Tony Kaye, all those amazing artists that I looked up to. Also learning how to touch people. When you do the short form commercials, you only have 30 seconds to grab the attention of the audience. I learned that through these masters.

PERRY: I felt that through Pavement’s story — the evolving sense of media culture, of marketing, of musicianship, of MTV had changed so much at that time. I wanted the film to keep in mind that it was an elegy for an era that I feel lucky to have gotten to experience as a young person. Back then you wouldn’t know what was coming. You would suddenly one day see, “Here’s a new video and this album comes out in two months.” There was no, “I saw online that they’re teasing something.” These things would just appear. The movie always for me had to be about the mystery of that era where something could be as simple as, “I read about it in a zine. I went to the store and I bought the independently released album. I don’t know if they made videos, I don’t watch MTV, I don’t have cable, but I saw them in concert and they were good.”

ÅKERLUND: I love to time travel back and remind myself of how stuff used to be. I wonder how a band like Pavement would do today. The era itself and the attitude were people looking for these cool bands. It was like 10 different genres happening at the same time. There was so much going on.

PERRY: What do you think is the reason that that ended that, other than the internet?

ÅKERLUND: I think unfortunately it’s hard to make money, or sell albums. Our artists come to me and say, “What do you think about illegal downloads and getting this and this?” I’m like, “Hey, I’m a filmmaker. I execute ideas and I don’t own anything.” It’s hard for me to say something about the fact that you don’t make millions on your art because I don’t. I got four billion hits on YouTube, but I don’t make a cent.” That’s more of a political discussion that shouldn’t be in this article. I’m sure you and I could talk like this for hours. We can continue over a drink or something.

PERRY: Yeah, whenever you’re in New York, we will.