ICON

How Photographer and Pin-Up Girl Bunny Yeager Pioneered a New Erotica

When Kareem Tabsch and Dennis Scholl sat down to reflect on Bunny Yeager, the subject of their new documentary Naked Ambition, one thing stood out: her unrelenting, almost supernatural drive. “She was just so hard on the hustle,” Scholl recalls. “She wasn’t Hugh Hefner’s favorite female photographer. She was Hugh Hefner’s favorite photographer for Playboy, entirely.” Notably, Yeager was the first woman to ever shoot for the magazine and soon became one of its most prolific contributors. Through sheer force of will, she carved out a place for herself in a male-dominated industry and helped define a visual language: the pin-up, girl-next-door aesthetic that can be recognized everywhere today. Naked Ambition extends beyond Yeager’s singular achievements to paint a portrait of an America reshaping itself alongside her. Tabsch and Scholl trace shifting attitudes toward sexuality, censorship, feminism, and the murky lines between empowerment and exploitation. In conversation shortly after the film’s release, the two went deep on Yeager’s sensational legacy—and the controversies that always trailed her closely.

———

TABSCH: Let’s start at the beginning. Gosh, you had already made what, one or two features by the time this started?

SCHOLL: Probably just one, Deep City. After that I was very excited about making a second feature. I was approached by a fellow who said, “You ought to make a feature about Bunny Yeager.” And I said, “Boy, that’s a good idea.” I went over to meet her and I said, “Bunny, I’m Dennis Scholl. I’ve made these films and I’m here to make a documentary about your life.” She just said, “Go away.” [Laughs] She said, “I’m much too busy with my books and my shoots. I really don’t have time for you.” She was 83 at the time. But for the next two years after that, I pestered her. And finally, at age 85, I got a phone call from her daughter who said, “Bunny’s ready to make the movie.” So I went and visited with her again and we scrambled together a very big crew—probably the biggest crew I’ve worked with before or since–and that day we started shooting. I shot some of Bunny’s models, and Bunny was supposed to come to set at 10. They called and said, “She’s running a little slow. She’ll come at 12.” At 12:00, they said she’d come at 2:00. At 2:00, they called and said she’d come at 4:00. And at 4:00 she went into the hospital—and she never left. She eventually passed. I was devastated. I put the film on a shelf. A number of years go by, and then you and I get together. You pick it up from there.

TABSCH: Yeah. We had done Bunny’s interview, and your start of the film sat on the shelf for a while, and then you and I had made a feature together–The Last Resort, which is about 1970s Miami Beach. It was the largest enclave of Jewish retirees in the country, and we tell that story through two photographers, Andy Sweet and Gary Monroe. And that film did much better than either one of us expected it to, right?

SCHOLL: I’ll say.

TABSCH: Yeah. [Laughs] It played in theaters in New York and L.A. and was distributed, and then Netflix picked it up. So we wanted to put the band back together and do another one.

SCHOLL: Well, because The Last Resort was such a big film for us, people kept asking me, “What are you going to do next?” And the one thing I’d learned about filmmaking is you never say, “I don’t know.” But I really didn’t know. [Laughs] So I quickly pivoted and said, “I’m going to make a film about Bunny Yeager.” I hadn’t looked at it for four or five years, but I immediately knew I wanted to work with you again. Of course, it didn’t work out the way we’d hoped, because we started to shoot a couple interviews, and then woke up one day and it was March 13th, 2020, and we lost another three years. But in 2023, we began to kind of pull the film together. It was a 13-year journey from when I asked Bunny to make the film to when it had its world premiere at DOC NYC. It was a tough one.

TABSCH: It’s crazy to think how long it took. We talk about this often: we are not those type of documentarian filmmakers. We love and respect those who say, “We’re going to spend eight years doing this one story.” But both our attention spans and patience don’t run that far. But this was the universe selling us, “Yo guys, slow the fuck down. It’s going to happen when it’s going to happen.” Ultimately, part of why the film’s called Naked Ambition, is because she was so ambitious and she always had another thing that she’s going to pull out of her hat, whether it was a dieting book or illustrations. So when somebody asks, “What are you going to do?” You’re like, “I’m going to do this.” And then we made it happen, didn’t we?

SCHOLL: Manifest–

TABSCH: [Laughs] Manifest it. I was going to use that word. I think Bunny was also at a more irascible state in her life. Being in her eighties, she’d been through a lot, she’d seen it all, and she could be a little grumpy. So it’s not shocking that she was like, “I don’t got time for a movie.” But the persistence paid off, because again, that’s probably something that she responded to, since she was so persistent in her own life and career.

SCHOLL: Yeah, I think that’s true. One of the things we talked about in the middle of the film is how she was a reluctant feminist. She was just so hard on the hustle. She always had game. She was always trying to do the next thing, and yet she paved the way for so many people after her. I mean, she was not Hugh Hefner’s favorite female photographer. She was Hugh Hefner’s favorite photographer for Playboy entirely. And she had a way with her models—just simply making them comfortable—that allowed them to really shine during the photo sessions. She also invented that “girl-next-door” look that became so important in cultural photography. So despite the fact that she w ould never have called herself a feminist, there’s a lot of other people that look up to her—people like Cindy Sherman and Laurie Simmons, the great photographers of the eighties, nineties, and forward. But she was tough as nails, and like you said, irascible. I tend to make films about irascible people, I think—between Clyfford Still and Bunny and Charlene, the Cuban ballerina dancer. They’re all really tough people because they feel like they have to be that way. She felt like she had to be that way to get where she was going, and she didn’t think it was because she was a woman. She just felt like the world is tough and “I’ve got to go make a living for my family,” because I don’t have enough income between my husband being a police officer and me, unless I step up and do this.

TABSCH: Yeah. I just find her work remarkable. It’s stunning, it’s beautiful, it’s timeless. But the thing I walked away most impressed with was her determination—this ambition of “Good enough is not enough. I want to do more. I’m going to do more.” Honestly, it was so much at some point that we couldn’t even chronicle it all in the film. But in the film, you see that she wrote books before, and they ran the gamut: How I Photograph Myself, which is probably her most famous one, but also My 600 Calorie-a-Day Diet, a slew of books about things that she was—

SCHOLL: Barely acquainted with.

TABSCH: Right, from confident to barely acquainted with. She acted, she had a nightclub act, she did have a nice voice. She did all of these things and seemingly kept doing more and more. She was pitching Playboy as late as the early 2000s. So she never slowed down, even though the world that she helped create had shifted so drastically.

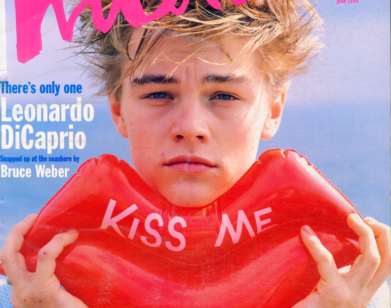

SCHOLL: I think also that the level of respect that she had is evident from those who talked to us for the film. The interview we did with Bruce Weber was just extraordinary. He told the funny story of how Bunny would see a woman on the street, would follow her home, knock on the front door, and say, “Hey, I’d like to photograph you nude.” If you did that today, they’d come in with handcuffs and take you away. [Laughs] But Bunny was fearless about that. So she didn’t understand why she never got hired by Vogue to shoot, because when you look at those magazines after Bunny, you see her. It’s just people taking her style and absorbing her style. Dita Von Teese was amazing to talk to for the film. She kind of told Bunny’s story through her own story, how she got to where she is as the most renowned dancer of all time. And also, Larry [King]’s incredible in the film.

TABSCH: Yeah. There were a slew of people we wanted to speak to because Bunny’s influence and tentacles were so far-reaching.

SCHOLL: We should talk a little bit about her family too, because we don’t want to make this story sound like it was all perfect. Bunny had a very difficult life and her two daughters did, too. And the dichotomy in the film is that one of the daughters led Bunny’s business side for many years, and the other daughter was appalled by what Bunny did and moved away, because she was so uncomfortable with it. I mean, it must’ve been tough as a kid to grow up and have your mom come pick you up in go-go boots and a miniskirt and looking the way Bunny did.

TABSCH: Yeah, I can’t imagine. But it was a very interesting part of the story. It’s not always cakes and flowers for everybody, and it certainly wasn’t for Bunny. She had a really tough time. She had this really kind of split inside her family where her daughters had really different viewpoints, and it created tension with their mom, but it also created tension between them. To their credit, both children sat and gave us these amazing interviews where they were very candid and very honest and they didn’t hold back.

SCHOLL: No, they didn’t. The other interesting thing is that the daughter that really didn’t like what Bunny did has a daughter who adored her grandmother and what she did. So the family really animates the film in a very different way than I’ve ever done before.

TABSCH: I think two daughters, Lisa and Sherry Lou, kind of serve as these avatars for the public. By and large, most people see Bunny’s work and love it and respect it and admire it, but there are still some people who see it and are like, “It’s exploitative of women. I don’t care for it.” And so Sherry Lou, who voices that opinion, represents the part of the population who thinks Bunny’s work is just naked pictures of women for men. And then there’s Lisa, who celebrates her mother’s artistry. They really are these amazing stand-ins for people who view Bunny’s work.

SCHOLL: Right, and when we make films, we try to tell a story of a time span—maybe in a single geography, maybe in a national way. But this film is no different. We use Bunny’s journey as a way of seeing how America evolves with regard to sexuality.

TABSCH: Yeah, that was the most exciting part: being able to do these two things, because it really contextualizes how ahead of her time Bunny was, and also the dangers of being a pioneer. Being a woman at this time and creating this kind of work was challenging the social norms of a very conservative America. One of the challenges was to make sure that we were able to weave in Bunny’s story at the same time that we were weaving in the elements of the changing country. And it’s funny: one of the ways that comes out—it’s almost like you cannot talk about Bunny without talking about Bettie Page, right? Bettie Page actually comes to Miami escaping the heat of a congressional hearing about obscenity—the Kefauver—if I remember correctly.

SCHOLL: Yeah. The other thing I really enjoyed about the film—making it and also delivering it—is how Bunny had this kind of re-explored, or redemptive coda at the end, where people started to circle back to her years later. Maybe partially as a nostalgia, and partially because the work was just so damn good. It was lovely to see her get a museum show at the Andy Warhol Museum, and at the museum in Fort Lauderdale. Those opportunities don’t come very often to artists, and Bunny’s star was really on the rise. And I think, fortunately, she felt that at the end of her life. Those last couple of years, she saw that the world was really appreciative of what she did. And I love that we were able to show her enjoying those moments.

TABSCH: We should talk a little bit about this world that Bunny created and how it looks today. She really helped push the envelope. She was really ahead of the curve. Then things changed. We went from the milder men’s magazines and Playboy to Penthouse and Bob Guccione’s operation, and then Larry Flint—

SCHOLL: Hustler.

TABSCH: —to Hustler. And that’s just gynecological. I think it’s the line I stole from Scholl—his description of Larry Flint’s work as “gynecological”— but it’s true. And then she kind of becomes a little bit old-hat and comes around later. But now we have things like OnlyFans and Instagram, and I can’t help but think that Bunny had an influence on both. I wonder if you’re thinking about that.

SCHOLL: Well, I think the great thing about the discussion is that it still continues. Some people think that anytime you shoot something like Bunny’s photos, it’s exploitive. Some people think that it’s very empowering. And you look at OnlyFans and the money that’s swirling around there, and it’s hard not to consider that.

TABSCH: Man, I think that if there’s a takeaway—both from our process and from the film—it’s that you can be whatever you want to be if you’re willing to put the work in, right? Maybe that’s too much of an American dream story, but if Bunny showed us anything, it’s that ambition coupled with determination and hard work goes a really, really long way. She faced incredible, incredible challenges, but she was so determined, so ambitious, and so hardworking. That combo–maybe it doesn’t always translate to bucks in the bank, but it does translate to people decades later sitting back and saying, “This is somebody you have to take notice of. This is somebody who’s an inspiration. This is somebody whose story deserves to be told and admired.”

SCHOLL: Absolutely.