literature

Martin Amis and Salman Rushdie on Cancel Culture and The Hitch

In the prelude to Martin Amis’s latest book Inside Story, the author not only speaks directly to the reader, but warmly invites us into his home, offers us a drink, shares the latest tidbits about his wife and children who will be join- ing for dinner, and assures us that the upstairs bedroom is ours to enjoy. “Oh, don’t mention it—de nada,” Amis insists. “The honour is all mine. You are my guest. You are my reader.” (One imagines the good fortune of landing in New York City and crashing in the Cobble Hill brownstone that Amis and his wife, the writer Isabel Fonseca, shared before it was damaged in a fire in 2016.)

With an unauthorized biography, the reader becomes, whether we like it or not, a thief, breaking into a public figure’s home to root through their stuff and unearth their secrets. But with a memoir, the author welcomes the guest in and allows us to snoop around at our leisure. Amis cuts to the chase, then, telling us to take what we’d like. But, as you might have guessed, Inside Story is no ordinary memoir. In fact, it calls itself a novel. In truth, it’s a hybrid beast, a record of a real life written with all the freedom of fiction—its style, tactical ingenuity, and narrative leaps—while also moonlighting as an advice book to young writers and a literary critique of some of the key influences on Amis’s work (Saul Bellow and Philip Larkin are high up on the list of saints).

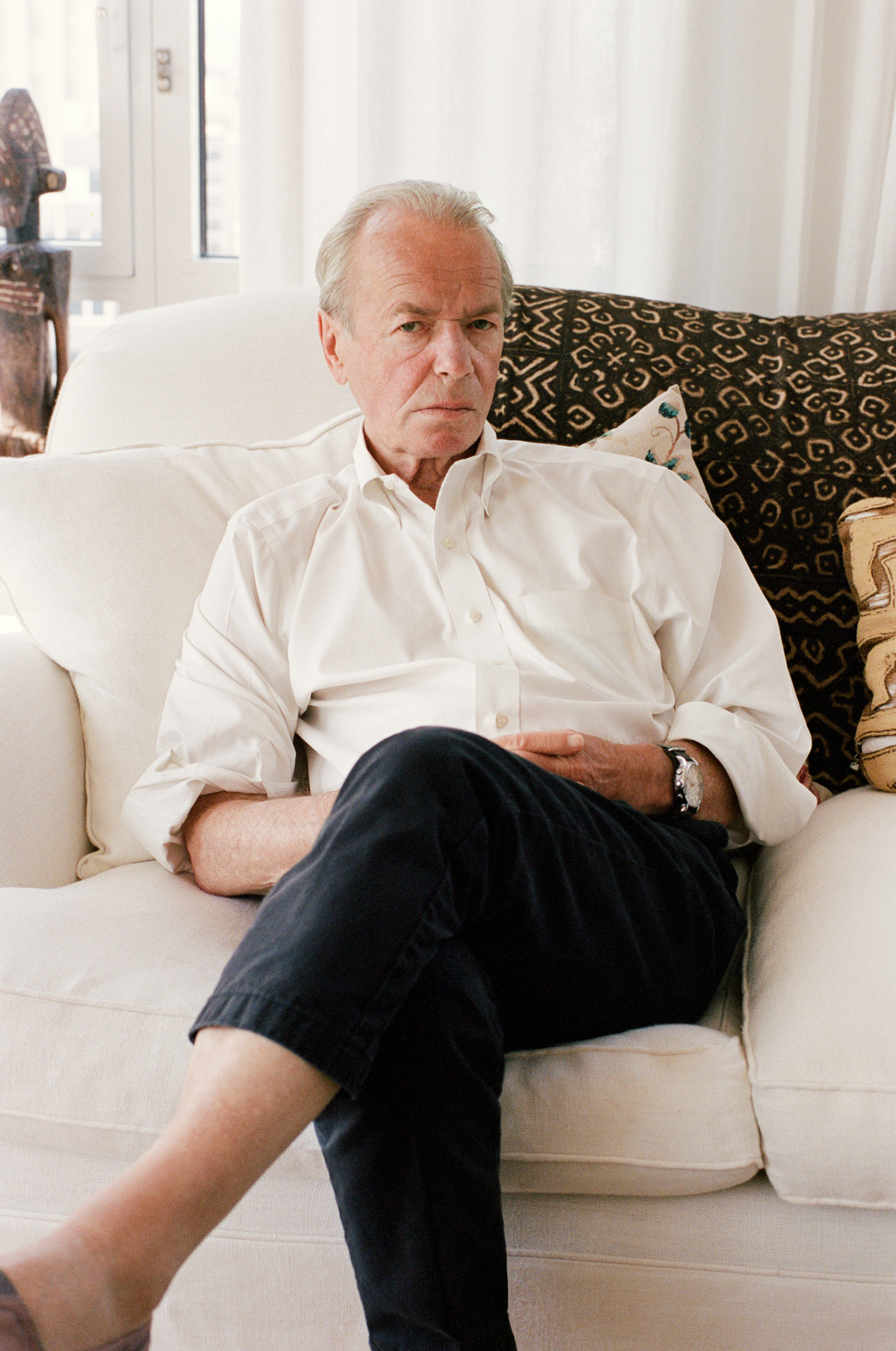

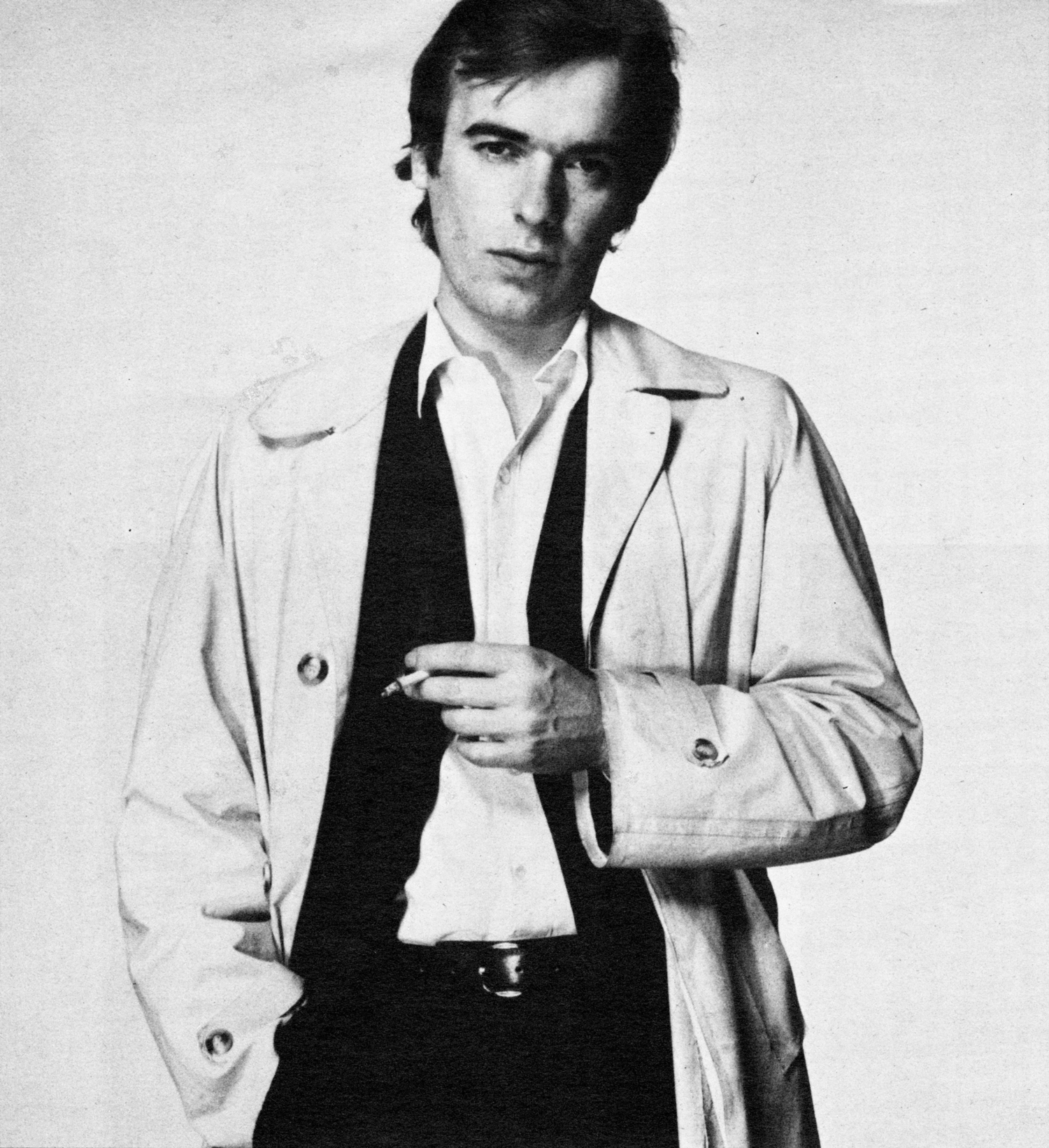

At 70, Amis is still a writer who refuses to play it safe. He has always been a provocateur; the son of the celebrated novelist Kingsley Amis, he released his 2000 memoir Experience with a cover that showed him as a towheaded boy puffing on a cigarette. Inside Story shares with Amis’s greatest novels (The Rachel Papers, London Fields, Money, Night Train—okay, really all 14 of them) his signature charming-rogue narrative style that manages to high- wire so brilliantly between the comedic and the emotionally calamitous. The main devastation of this book involves the death of Amis’s lifelong friend, the essayist and public intellectual Christopher Hitchens (Hitchens died in December 2011 after battling Stage 4 esophageal cancer). The Hitch, as he was known, was uniquely clever and cunning, and Amis writes beautifully on the subject of their close relationship, as when he describes a normal meal: “Lunch with the Hitch was still lunch with the Hitch, in the sense that you got there around one, and left there while the place was filling up for dinner. His interest in food, never great, had now declined into indifference, but he drank his one or two Johnnie Blacks and his half a bottle of red wine (‘sometimes more, never less’ was his rule), and he talked with undimmed fluency and humour for six or seven hours—to such effect that it would be a sin, he said, not to round it off with some cognac.”

Speaking of impressive friends, Amis acknowledges their presence early on—“Oh, and I apologize in advance for all the name-dropping. You’ll get used to it”—when he introduces us to his pal Salman Rushdie, another literary superstar who has, in recent years, made his home in New York. Amis and Rushdie spoke this past July about cancel culture, the proper length of novels, and why authors might belong to a generation but never to a movement. — CHRISTOPHER BOLLEN

———

SALMAN RUSHDIE: Martin, this is a very unusual book.

MARTIN AMIS: Yes, it is. I didn’t strive for originality, but I kept thinking, “I don’t think there’s another book that does this.”

RUSHDIE: It really is like nothing else I’ve read. In the book, you talk about autofiction, and it doesn’t feel like [Karl Ove] Knausgård or Amélie Nothomb, or those normally thought of as autofiction writers.

AMIS: Perhaps it’s worth saying that I began this novel 18 years ago. I felt cramped and compromised—I was writing fiction about real people. And I still think that’s an extraordinary liberty to take. It was only after Christopher Hitchens died in 2011 that I felt moved to go back to it. The fact that all the protagonists were dead, sad to say, did seem to give me a bit of room. You and I have both written memoirs, and we know what that’s like. It’s all laid out before you, and your job is transcription, really, with some shape and all the rest of it. But with a novel, there was room for invention and rearrangement. I know Saul Bellow doesn’t come naturally into this category, but he certainly felt he was writing about real life, and he had terrible anxiety attacks about who was going to sue him, so he would change the names of major characters at the last minute. Those kinds of problems tend not to come up in the writing of what I would call an “art novel.”

RUSHDIE: There were all kinds of parallels in Bellow’s life and novels— Herzog for example, with the wife running off with somebody else. But I didn’t feel like I needed to know that in order to understand Herzog. What you’re doing is often keeping people’s real names, many of them dead. And yet some names you did change. I wondered what the principle was behind that.

AMIS: It was left to impulse. Sometimes it felt right to name a character bluntly and other times not. All the big decisions are made automatically because your subconscious has been working on it. I wasn’t going to call Saul Bellow “Solomon Beloz” or anything like that. No deliberate disguises for people who are well-known. And that was liberating, too. But it certainly is an odd novel with chunks of lit crit in it. I’d have thought that only someone interested in literature as a philosophical proposition would be as interested in it as I am. As with all novels, it was a gamble.

RUSHDIE: When you’re writing these very detailed and evocative portraits of people like Bellow and Christopher, I had the sense that you’re telling us the truth. You’re telling us how they were and what they said and what they did. To what extent is that so?

AMIS: I did invent conversations with Christopher and, to a lesser extent, with Saul, and then a lot with Philip Larkin. But I know what their voices were like and what their views were. So even if they never said it in my presence, I still trusted the verisimilitude of it. There is invention and rearrangement to suit various artistic considerations. Writing stylizes. A novel is a stylization of reality. I always think that the difference between a novel and real life is the difference between a woman’s shoe and a foot. The shoe, with the stiletto heel and the curved sole and the chisel arrangement at the front, really doesn’t look anything like a foot. Life is the graceless trotter down there at the far end of your leg. It’s really clunky. I even took some liberties with my own character and made myself more neurotic than I am.

RUSHDIE: You address the reader directly throughout the book. Do you have a distinct sense of who your reader is? Can you feel them when you’re writing?

AMIS: The relationship between the writer and the reader is a mysterious one, and rather unexamined in my view. At its simplest, it’s a matter of straightforward transmission: I am telling a story. But it goes much deeper than that, until reader and writer become identical, almost indivisible. One mustn’t, of course, baby the reader, but one must be very considerate of them. The frame of this novel is a direct dialogue with the reader. My ideal reader is very young. How old is yours?

RUSHDIE: I’m happy to say that I still get some young readers. You have this fear that your reader is going to age with you, right?

AMIS: It’s orgiastic to come across a young reader. You think, that means my afterlife is going to be as long as their life. But I think I write for my younger self.

RUSHDIE: You have the sense of yourself looking over your own shoulder?

AMIS: Well, I do think you write the novels that you want to read.

RUSHDIE: Do you think you might write a more instructional book on the nature of writing?

AMIS: No. I actually thought there would be more of those guidelines on how to write sentence by sentence. But let me make a distinction first. Every frequently published writer has some genius. For the most part, you rely on talent. But as you get older, the genius bit shrinks. The craft aspect of it, the technique, gets more practical. So genius is that god-given altitude of perception—what you must have felt when you were writing Midnight’s Children, or like Saul Bellow did when he wrote The Adventures of Augie March.

RUSHDIE: That goes away. I remember, a long time ago, having a conversation with Kazuo Ishiguro whose view was, basically, if you haven’t written something by the time you’re 40, you’re screwed. He’s a very methodical person. He researched what age great writers were when they had written their greatest work. How old was Flaubert when he wrote Madame Bovary? How old was Tolstoy when he wrote Anna Karenina? And his conclusion was that if you haven’t done it by 40, you’re essentially screwed. And if you haven’t done it by 50, you’re completely screwed.

AMIS: There’s a lot to that. The great books are essentially written by people in their thirties. Jane Austen was in her early twenties when she wrote Northanger Abbey and Pride and Prejudice. Writing is not like philosophy, where you face professional senility in your late twenties. And it’s not like poetry, where the creative urge tends to weaken in your fifties or sixties. With fiction, you toil on until an inner voice whispers that the time has come to hold your peace.

RUSHDIE: Some poets go on. There’s Czesław Miłosz, Seamus Heaney, and Wisława Szymborska, all of whom went on into advanced old age. When I finished reading your book and put it aside and thought about it for a while, it felt to me like a self-portrait.

AMIS: Well, “apologia” is perhaps a better term. A sort of self-justification. All the advice I give about writing is really just how I go about it. But sure, all novels are self-portraits. This one is particularly heart-to-heart.

RUSHDIE: A self-portrait through the portrayal of people who have been very important to you. Was Christopher really the starting point?

AMIS: I always knew he would dominate the narrative because that’s what he always did. You were close to him. You know how unstoppable he was. That’s all true in the novel, the fact that I never allowed myself to think that he wouldn’t somehow defeat Stage 4 cancer. The remission rate is pitiful. When I wrote an essay about Hitch halfway through his 19 months of being mortally ill, I had a conversation with Ian McEwan where he said, “When you criticize him, his weaker stuff, you’re not wrong, but does he need to hear that now?” And I said, “What do you mean now?” And he said, “He’s dying.” And I didn’t say it, but I really wanted to say indignantly, “He’s not dying.” And of course, the numbers were terrible. Not until the day he died did I accept it.

RUSHDIE: I must say, I felt that when we were in Houston at [the record producer and publisher] Michael Zilkha’s house for what, as it happened, was Christopher’s last birthday. He was quite up that day. He seemed not at death’s door. But I remember coming away from that day thinking, “He doesn’t have long to go.”

AMIS: Well, at some point, the doctors told Christopher that he couldn’t attend some family event, and Ian asked him, “Do you think you’ll never see England again?” Christopher admits in his little book Mortality that he bridled, but he said that Ian was quite right to ask, and it was exactly that which was bothering him. What remains a mystery to me is how much Christopher believed that he could survive. It’s the complicated question of morale and not admitting defeat, or curling up with your face turned to the wall.

RUSHDIE: Well, he went on working up until almost the last minute. I remember when Hitch-22 was published [in May 2010]. He had an event at the 92nd Street Y, and they asked me to be the moderator. He was at his most brilliantly Hitch-like, entertaining this packed room. Afterwards, we had dinner at a little restaurant across the street. It turned out that earlier that morning he had been given the news of the extent of the cancer, and had essentially been given a death sentence. I thought, “What an extraordinary thing to be able to do, to receive that information and then come out in front of 1,000 people and perform.” It spoke to his willpower and maybe his willingness to believe that he would beat it in the end.

AMIS: When I saw the candid photograph on the back of Mortality, which was published posthumously, I felt like he’d actually communed with the idea of death a great deal, as he would. But I never had those conversations about death with him. They were internal.

RUSHDIE: This is a book in which arguably the four most important people— your father Kingsley, Philip Larkin, Saul Bellow, and Hitch—have died. The book feels, in a way, like an examination of death. I’m wondering how much that’s a subject to you now.

AMIS: Well, I wonder how much there is to say about death. There’s an early bit in a Saul Bellow book—I think it’s Herzog—where he meets a lady friend who’s showing the first signs of age, and he describes the lines around her eyes and says, “Death, the artist, very slow.” And I think death is an artist. There’s not much you can do about it.

RUSHDIE: If Christopher were still around, what would he make of the world today? There’s this double crisis we’re in at the moment; on the one hand this pandemic, on the other hand this very urgent reexamination of race relations in the country, and all of that happening underneath the umbrella of Trump. You and I both signed this Harper’s letter [“A Letter on Justice and Open Debate” calling for an end to cancel culture, published July 7, 2020]. Somebody asked me the other day, “If Christopher were around, do you think he would have been canceled because of all his outrageous remarks?”

AMIS: Like his essay, “Why Women Aren’t Funny.” Wrong!

RUSHDIE: Wrong, yes, wrong! But one of the things one should be allowed to be is wrong.

AMIS: Contrarian was almost Christopher’s middle name. And he did show his contrarian spirit on quite important things like the Iraq War and the voting for Bush/Cheney in 2004. I don’t know for sure how he would have reacted to Trump in 2016.

RUSHDIE: Well, he would have had a problem because he hated the Clintons so much that for him to support Hillary might have actually been impossible.

AMIS: That’s a good point. I reread just the other day his last attack on Hillary Clinton. He zeroes in on the fact that she lied about her name. She said, “I was named after Sir Edmund Hillary.” And Christopher gleefully points out that Sir Edmund hadn’t yet climbed Mount Everest by the time Hillary Clinton was born and this lie alone should have disqualified her.

RUSHDIE: We have somebody who’s a more outrageous liar in charge of things right now.

AMIS: Remember how indignantly he pointed out that Reagan told a lie every day? Trump tells one every 10 minutes.

RUSHDIE: Now it’s 100 lies a day.

AMIS: But Trump is the nemesis of all sorts of ways of thinking. He’s anti-expertise, anti-allegiance, and—

RUSHDIE: Anti-journalism. And that’s who Christopher was, apart from anything else. He was a journalist.

AMIS: You know, I always thought Trump was a one-term president if that—with or without COVID. Americans have a certain appetite for crassness and chaos, but that appetite is soon sated. And he’s clearly unreformable. Lying his head off, as a strategy, clearly wasn’t going to work as a response to a pandemic, but he tried it anyway.

RUSHDIE: No, his only method is to double down.

AMIS: To never change his thoughts.

RUSHDIE: There’s that line in [George Bernard Shaw’s] Arms and the Man where the soldier says, “Never explain, never apologize.” That seems to be his motto.

AMIS: Just attack, attack, attack.

RUSHDIE: Now, here are some questions writers always get asked: “What is your writing process? Do you write every day? Morning or evening?” The most boring questions of all.

AMIS: Right alongside, “Do you base your characters on real people?” Well, I was wondering what to write next after finishing this novel, which I more or less did toward the end of last year, and I did start something. It was only a short story that I haven’t finished yet, about lynching, which now feels quite topical. George Floyd was a victim of police brutality, like so many others, but the murder of Ahmaud Arbery, the Georgia jogger, was a textbook lynch- ing. Still, the subject is so heavy with historical complication that I wake up with the sense that I have an anvil on my chest. That’s an ominously informative moment for a writer—how you feel when you wake up. Let me ask you. How do you feel when you wake up? What’s your first feeling?

RUSHDIE: Most days? The need for coffee. But when I’m in the middle of writing, my first feeling is a desire to get to the desk as fast as possible. I take the coffee to the desk.

AMIS: Those days are gone for me. It’s more like a sort of Stickle Brick operation, another paragraph here and there. Having exhausted myself with a long novel, some mornings I wake up thinking, “I’m not going to try it this morning. Maybe I will around drinks time.”

RUSHDIE: Well, this one’s almost 550 pages. That’s a big effort. I can’t get anywhere close to that anymore. The last couple of books came in at slightly under 400. But I’m writing this thing now that I suspect will be under 250. I just don’t think I have it in me to write another really big book.

AMIS: It’s very hard to keep nearly 550 pages in your head. Richard Ford, after he finished The Lay of the Land, which is enormous, said, “I’m never going to do that again.” But then his next book was just as long. So I don’t know. I feel I’m only going to write short stories and novellas from now on. Chekhov said, toward the end of his life, “Everything I read strikes me as not short enough.” And I agree.

RUSHDIE: It might be apocryphal, but [Jorge Luis] Borges is supposed to have said about [Gabriel] García Márquez’s great novel, “It’s too long. It should be just Fifty Years of Solitude.”

AMIS: Well, Borges’s average story length is, what, eight pages?

RUSHDIE: Certainly under ten.

AMIS: I think that’s what the older writer should reach for.

RUSHDIE: I like the people who are very good at writing long stories—V. S. Pritchett, Stefan Zweig, people who can write a 40-page story.

AMIS: Like Alice Munro.

RUSHDIE: It’s a real skill. You’re getting almost a novelistic amount of pleasure from 40 pages. You don’t think you’ll break 500 pages again?

AMIS: I’ve broken it before, but definitely not again, or so I feel.

RUSHDIE: Actually, the longest book I ever wrote was Joseph Anton: A Memoir. That actually broke 600 pages. And I don’t see myself doing that again. I remember, when I finished it, thinking that it was a bit too long, and all the English-language publishers in New York and London and Canada agreed with me. But no one could agree on which 40 pages to cut, so it ended up being 40 pages too long.

AMIS: When Saul Bellow was asked, “What’s Augie March about?” he said, “It’s about 200 pages too long.”

RUSHDIE: You know, when we mentioned Ishiguro earlier, it occurred to me that way back when we were all young and beginning, there was this attempt to group us together as a kind of generation. At the time, we all resisted that idea and even said, “Not all of us know each other. Some of us like each other. Some of us don’t. Some of us admire each other’s books. Others don’t.” We didn’t feel like a generation. But I’m wondering whether you feel like one now? Because now I kind of find that I do a little bit.

AMIS: I certainly feel part of a generation that saw a fairly radical change in the way novels are written and in the way novels are read. You can no longer expect the reader to surmise, to infer, to second-guess. As an adaptation, writers will cease to imply, to hint, to tease. Now they have to declare.

RUSHDIE: Yeah, none of that goes anymore.

AMIS: No. And in addition, the novel has had to speed itself up—in answer to an accelerated reality. Bellow’s Humboldt’s Gift—long, static, and digressive—spent several months as a bestseller in the 1970s. That audience has more or less disappeared.

RUSHDIE: That was also true of Portnoy’s Complaint, and it was true of Slaughterhouse-Five and a whole range

of books of that generation. Literary fiction had a much bigger readership. But do you feel that all of us who were there, you and Ian [McEwan] and Julian [Barnes] and “Ish” [Ishiguro] and me and Bruce Chatwin and Angela Carter and all the people who were around—did that feel like a cohort to you? Or does it just feel like an accident that you were around with these people at that time?

AMIS: An accident. When I was at The New Statesman [as a literary editor in the early 1970s], my colleagues were Christopher Hitchens, James Fenton, and Julian Barnes. No one arranged that. It was just a coincidence. We were all from very different backgrounds, so it looks that way generationally in retrospect, but it didn’t really feel that way.

RUSHDIE: Most of the time, I think that while many of these writers are writers whose work I really like and try to follow, I don’t see that we’re engaged on the same project, not in the way, for example, the Magic Realists were, or the French Surrealists. They were a gang, and they were doing something that they felt was a team effort.

AMIS: That’s the way “movements” start. Ambitious young drunks, late at night, saying, “We’re not going to do that anymore. We’re going to do this instead.” But in the end, they all go their own way.

This article appears in the September 2020 issue of Interview Magazine. Subscribe here.

———