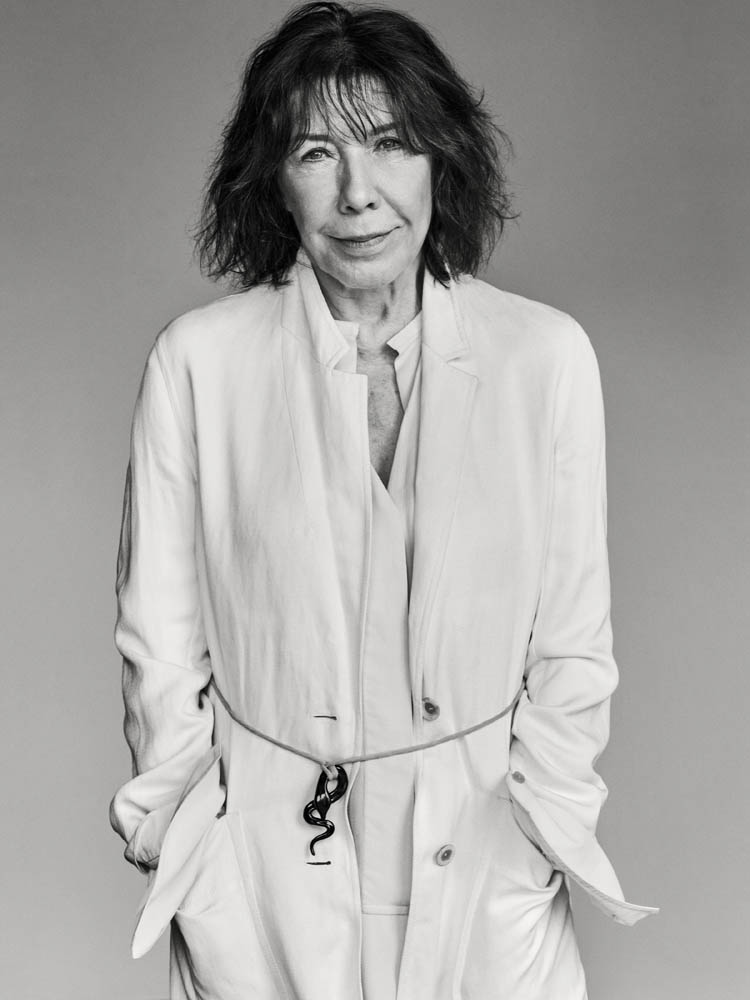

Lily Tomlin

The limo swept in front of the place . . . I get out in that blue dress and white fox fur, and I sweep into the Improv, do ten minutes, and I sweep out, get in the car, and drive away. LILY TOMLIN

Inspiration takes many forms, but it’s rarely pure. Still, that’s precisely what Lily Tomlin has offered over the course of her 50-plus-year career. In her naturalness of expression and dramaturgical clarity, Tomlin has created a universe of difference where no one is out of place. What unites her more famous characters—Ernestine, the telephone operator; Edith Ann, the pint-sized philosopher; Tess, the Bag Woman; Rick, the singles guy; and so on—is the enormous heart she and her longtime partner and collaborator, the writer Jane Wagner, instill in creating people who aren’t simply portraits of what it’s like not to fit in, but the joy to be found in one’s trademark difference.

Born in Detroit, in 1939, Mary Jean Tomlin is a daughter of the South once removed. Her late parents, Lillie Mae and Guy Tomlin, were Kentucky natives who made their way north for a better life and settled in a working-class neighborhood of the city. Taking her mother’s name in 1964, Lily Tomlin gave voice to that particular and peculiar birthright in classic pieces such as “Lud and Marie Meet Dracula’s Daughter,” where a teenage girl terrorizes an older couple.

Throughout the years, Tomlin has worked with a number of unique stars on and off the comedy stage and in and out of Hollywood—Jane Fonda, Bette Midler, Art Carney, Robert Altman, and Steve Martin come immediately to mind—but her only peer in terms of the art of the monologue was her late friend Richard Pryor, whom she first met when she approached him about working on her 1973 CBS special Lily. In her upcoming film, Grandma, and her new Netflix series, Grace and Frankie, in which she co-stars with her old friend Fonda, Tomlin continues to inspire because of what she projects: the deep art behind an ephemeral form, otherwise known as performance. I had the great, good fortune to see Lily recently in a restaurant in Times Square when she was passing through town between performances of her touring one-woman show.

HILTON ALS: You look so gorgeous. What are you doing in New York?

LILY TOMLIN: I played a show in Westbury, the Sunday matinee.

ALS: How was it?

TOMLIN: It was good. Afterward I went to dinner at Orso with Robin Morgan [the writer and activist]. She had come to see the show.

ALS: I would have taken you to Orso today! For the liver—Jane Fonda’s favorite thing to eat there.

TOMLIN: [laughs] Well, we both had the liver and it was kind of dry. Must have been because it was Sunday night. I stayed in the hotel all day yesterday because my face froze off Sunday night. And tonight I’m going to go see An American in Paris.

ALS: Tell me what you think of it! I haven’t seen it yet.

TOMLIN: Well, tomorrow night I’m going to go see Beautiful [The Carole King Musical] because we know one of the producers, Harriet Leve. Jane, Harriet, and I are all working on developing a screenplay together with Jane Anderson, who wrote that cheerleader movie [The Positively True Adventures of the Texas Cheerleader-Murdering Mom, 1993] years ago and recently did the screenplay for Olive Kitteridge.

ALS: You used to be a cheerleader, didn’t you?

TOMLIN: [laughs] Sort of. Jane’s writing a screenplay based on the Beebo Brinker books, those gay ’50s and ’60s pulp novels, with me in mind as the older woman.

ALS: They were pulp lesbian novels, right? I’ve never read them. Are they fun to read?

TOMLIN: Yeah, they’re fun.

ALS: You really do look radiant, Lily. I think it’s because you’ve got a huge hit at Sundance, the film Grandma with Sam Elliott and Elizabeth Peña. Who is the girl who plays your granddaughter?

TOMLIN: Oh, that’s Julia Garner.

ALS: And I love that Sam’s character is still in love with you in the film. I love his voice, “I find that as I grow older, old shit just bubbles up.”

TOMLIN: “It bubbles up out of the tar.”

ALS: You can tell his passion for you never waned. His character has 11 grandkids, and I love how she can’t even believe that he would still care. How did this movie come about?

TOMLIN: I’d done Admission [2013] with Paul [Weitz] and we hit it off. His mother is the actress, Susan Kohner, who I was delighted by. So he called me up one day and said, “Could we have coffee?” He told me he was writing this script, and he was kind of writing it with me in mind. We talked about that, and the theme of it, and everything else. And I just jumped in.

ALS: When a director gives you a call like that, do they want your input into the character?

TOMLIN: I think they always want some input, but nothing catastrophic or life changing. I just tell them what my own experiences are.

ALS: Your work has evolved and keeps evolving. This character makes so much sense at this point in your career. Did you feel that it was a big chance that you were taking with this film?

TOMLIN: I had a lot of faith in Paul. I liked the idea of working fast and hard. And it just felt right. It felt good. And there were so many good people: Julia, Marcia Gay Harden, and Sam—I love him. And Judy Greer, John Cho, and Laverne Cox.

ALS: I know Laverne’s twin brother.

TOMLIN: Oh, you do?

ALS: For years. His name is M. Lamar, and he’s a great eccentric and great singer. What an amazing family. I remember Katharine Hepburn, when she was doing Long Days Journey Into Night [1962], once said something to the effect that she wasn’t afraid because she felt so supported by the words. When a performer also feels supported by the cast and the director, it makes them feel safe to fly.

TOMLIN: Yeah, it was easy. Maybe it was the right time.

ALS: Now tell me about the Lily and Jane Fonda project on Netflix. I remember hearing about it a couple years ago.

TOMLIN: It’s about two women of our age. Martin Sheen is her husband and Sam Waterston is mine. We’ve been married to them for 40 years. They’re law partners. They take us out to dinner. Our characters don’t like each other: I’m more free, I’m a painter, I’m more liberal; she’s a bit conservative, uptight. We think our husbands are going to finally retire, and we’ll be rid of each other, because we have a vacation house together, we go on holidays together. I’ve got two sons, she’s got two daughters, and we’ve just been thrown together all our lives. And our husbands sit us down and they tell us that they’ve been law partners for 40 years, but they’ve been having an affair with each other for the last 20 years, and they’re going to divorce us now, because they can get married, and they want to. So the rug is pulled out from under us. Our lives are just turned upside down, and it’s how we survive and how we bond and reinvent ourselves.

ALS: How did this show come about?

TOMLIN: I think Marta Kauffman had the idea, and I’m with the same agency as she is. I had worked for her agent’s father, Marvin Josephson, back in the ’60s. I was his assistant bookkeeper in New York. But when I first came to New York, I wanted to work at Le Figaro Café. That was the hot place to work at that time.

ALS: They didn’t hire you?

TOMLIN: No, they had a waiting list a mile long. And I had spent my last 15 dollars on dinner there. I got into town—

ALS: From Detroit. Did you drive yourself?

TOMLIN: No, I took a nonscheduled propeller flight. It cost 19 dollars one way on Continental. I had a girlfriend from college. I didn’t know her that well, but I called her up and asked her if I could stay with her for a few days, until I got settled. I’d just seen Holly Golightly in Breakfast at Tiffany’s. It was 1962.

ALS: So you were just going to get out of the taxi with your tiara on.

TOMLIN: And go up to a brownstone with a little tree in front. My friend lived above the B&H Dairy Lunch on Second Avenue near Seventh Street. I walked up, and she came to the door and had a sweatshirt on and was smoking a Lucky and looked depressed. [laughs] She was living there with a painter. Franz Kline had just died in ’62, and this guy was taking on Kline’s style. You know how a railroad flat is—just a window on the street, then there’s a teeny window on the airshaft in the back with a three-quarter room for a three-quarter bed. He and my friend hated each other. She had lived here with Trudy [Katzman], who’s still a friend. She lives up in San Francisco now, but she had married Allen Katzman, who was one of the founders of The East Village Other. We were in the hub of East Village activity.

ALS: And your college friend hated the painter.

TOMLIN: Yeah, they took him in the wintertime, but he wouldn’t leave, because the rent was, like, 32 dollars. And then Trudy married Allen, and she moved out.

ALS: Where were you sleeping?

TOMLIN: The painter had a rollaway that he slept on all day. I could have slept on his rollaway but that would have been fraternizing. They had a footlocker with a round top and I padded it up with blankets. There were roaches, unbelievable roaches. And she and the painter had written to each other on the walls, at eye-level, “Fuck you, motherfucker cocksucker. I fucking hate your fucking guts. I’m going to fucking kill you.” They didn’t speak; they only wrote to each other. [both laugh] I tell you, this would be a screenplay if it weren’t so long ago.

ALS: Amazing.

TOMLIN: He would paint all night and sleep all day in the front room, so he dominated the apartment. And he had these paintings hanging on every wall. I must have stayed there for a couple of weeks; I don’t remember. I got in on the Saturday before Easter, after finals or something. I was going to New York because I’d done a rich woman in a variety show that the university kids at Wayne State put on every year to raise scholarship money. And I was a big hit. It was the only relevant thing in the show; it was about a Grosse Pointe matron, and Charlotte Ford [the daughter of Henry Ford II] was making her debut just at that moment.

ALS: So perfect timing.

TOMLIN: It was just perfect. I just blew the roof off the place. Everything else was like a takeoff on Gunsmoke or something. So I did Mrs. Audley Earbore III. Later, on Laugh-In, it was “The Tasteful Lady.” I went on all the local TV shows in Detroit. I’d go with a hat and fox furs and gloves and everything else, and I’d do the bit and then I’d get up there like that and spread my legs. [laughs] And everybody just fell for it, so I said I’m going to go to New York and be an actress. So that night my friend and I went to dinner at Le Figaro. Before I left Detroit, I had borrowed five dollars from nine friends. I had $45. And the plane ticket cost $20. And then I spent about $15 or $20 at the thrift shop. I bought a cream-colored trench coat, like Holly Golightly had. So I had about $15 left, and I said, “I’ll try to get a job at Le Figaro.” Instead of being an intelligent person and going in and saying, “I’d like to get a job here as a waitress,” I go and eat dinner first and then I didn’t have any money left. And my friend didn’t have any money, so I go and buy a Times that night. I look up all the jobs, and I planned to get on the bus and go get a job. And because I had worked as an assistant bookkeeper in Detroit, after school, that seemed the easiest place to start.

ALS: You always had a head for figures?

TOMLIN: On the simplest level. Nothing too complicated. [laughs] I would be hard put to compute your thyroid levels. Anyway, the Fifth Avenue bus went uptown, so that Monday I started at Eighth Street and stopped every few streets. And finally I get to midtown at lunchtime, and that’s where Broadcast Management was, at the Canada House. So I went up and it was their lunch hour, and the bookkeeper said, “Come back after lunch; the boss will be back then.” When I got back,I wrote out a résumé and got hired right away. I went to work on Tuesday, and we got paid on Wednesdays. I got paid for two days out of five. Eventually, Louis came to live with me.

ALS: Louis?

TOMLIN: Louis St. Louis. I knew him from Detroit. He became the composer and arranger for the Grease musicals and the musical director for Smokey Joe’s Cafe. He’s a songwriter, piano player, raising-the-church gospel. Anyway, Trudy came over in the morning when my friend and I were still living in the railroad flat, and she said, “Get up. There’s an apartment for rent in my building around the corner on Fifth Street, between Second and Third.” We ran over there and it was a pretty good apartment. Like, it had a bedroom with doors on it. [laughs] We got that apartment.

ALS: You had the money because you worked for a couple of weeks.

TOMLIN: I had the money. That was the trick. Well, I also had sent home for some money. I’m getting all the things mixed up a bit; it’s been about 70 years! [laughs]

ALS: But your parents knew that you always worked.

[When I waitressed] at Howard Johnson’s, I ducked down behind the counter and used the microphone. I’d say, ‘Attention, diners. Lily Tomlin, our waitress of the week, is about to make an appearance on the floor. Let’s give her a big hand.’ LILY TOMLIN

TOMLIN: Oh, yeah. I always had a job. After I lived in that old apartment on Fifth Street, I moved downstairs to the first floor. I had Louis come.

ALS: Louis took the place of your friend?

TOMLIN: Yes. She didn’t work, and I worked all the time. I got a job as a waitress, and I had the job as an assistant bookkeeper. We had kids from college crashing on our floor. And I’d get up on Sunday morning at 6 o’clock and go do breakfast over in Howard Johnson’s. But then I moved. One of the most wonderful things that happened to me on Fifth Street was that I had a little blue laminated coat and a blue princess dress, and I had a pair of Ferragamo shoes.

ALS: You were getting to be a lady.

TOMLIN: Yeah, I’d dance in the fountains at the Seagram [building]. I went out one night with a friend and her boyfriend, and we danced in as many fountains as we could find. [laughs] I was just totally invested in Holly Golightly and Suzy Parker in The Best of Everything [1959]. Oh God, it’s embarrassing.

ALS: Did you take acting classes?

TOMLIN: Well, I went home at one point. I went back to Detroit because they beat up on me so bad at the agency, the girls at work. They were just bossy. From the Bronx and very bossy. And I couldn’t understand them anyway. And then Marvin started merging with a bunch of small agencies, and he eventually became I.C.M. So I went home to Detroit and stayed for a couple of years, because I worked at the Unstabled Coffeehouse [a Leftist bohemian enclave and cabaret], and I would do Beckett’s Happy Days. I was in my early twenties and I was playing Winnie, who’s supposed to be, like, 50, buried to her neck in the sand hill. And that’s where I discovered Ruth Draper [the 20th-century monologist, known for her repertoire of characters], at the Unstabled. Jack Slain, an older guy who was a lawyer, would come and hang out at the Unstabled, and I would do sketches. He said to me, “Have you heard of Ruth Draper? I think there are recordings of her at the library. You should go listen to her.” And that was an epiphany. I discovered her on records. And then later I met Charles Bowden, who was her producer.

ALS: And he did a lot of things on Broadway.

TOMLIN: Yeah, he was a Broadway producer, and he produced Ruth at the same time. Anyway, my head’s abuzz.

ALS: No, but this is a good buzz. When did you decide that you’d have to go back to New York?

TOMLIN: I wanted to, but I knew I didn’t know anything. When I was in New York that first summer, I played Kitty Genovese in a little documentary, but it never got finished. I was at a party in the Village, and a filmmaker came up to me, his name is Robert Young; he’d actually go on to direct Jane Wagner’s teleplay J.T. in 1969. I had got so beaten-up making that Kitty Genovese movie, because the guy he hired to attack me was not an actor, and he dragged me across the sidewalk, so my elbows, my shoulder blades, every little bone on my body was rubbed wrong. I had taken a picture of myself on the gurney, dead, but my eyes were open. And I used that as an eight-by-ten for a couple of weeks. I didn’t have any job offers.

ALS: [laughs] I love that it was your eight-by-ten.

TOMLIN: I was invited to go on an audition for Julius Monk at Plaza 9. I tried to get Louis to teach me how to sing a song, because I’d never auditioned for anything. And I had an old wind-up Victrola. Of course, it didn’t keep time.

ALS: [laughs] You were singing at 78 rpms.

TOMLIN: Yes, and my favorite song was, “There’s Not a Real New Yorker in New York” by Frances Maddux and her Play Boys. So I go and try to sing that song for Julius Monk. [sings] “I’d like to know where real New Yorkers go.” And he had a tuxedo on; he wore a tuxedo all the time. He was very famous in the cabaret world at that point. I had a skirt and a blouse that I’d dyed mauve at a laundromat on Second Avenue for this audition.

ALS: And what were your shoes?

TOMLIN: I never could wear high heels, but they were high heels. I suffered for years trying to wear high heels. Because there was not too much of an alternative back then.

ALS: That’s what’s so brilliant about you—you just incorporate things into your performance. It’s part of the story of Lily becoming Lily, basically.

TOMLIN: I guess so. Oh, I was in a mime show that first summer, too.

ALS: So where did you work when you came back to New York?

TOMLIN: I think that’s when I started doing waitress of the week at Howard Johnson’s on 46th and Broadway, where I ducked down behind the counter and used the microphone. I’d say, “Attention, diners. Lily Tomlin, our waitress of the week, is about to make an appearance on the floor. Let’s give her a big hand.” And then I’d go out and perform, because my tips would rise. I didn’t think of it as performing. I just thought I was having a good time, pulling a prank.

ALS: How long did you work at Howard Johnson’s?

TOMLIN: A few months. I quit. I got in a fight with the cook, because they could so easily use the soft butter to smear the toast. Before they put the toast on the plate, all they would have to do was swipe it once. Instead, people would get the toast, it would be cold, and they’d try to smear cold butter on it and the bread would break up, so I just fucking blew it one day. I threw off my apron and said, “I quit.”

ALS: [laughs] Were you auditioning at all?

TOMLIN: Not much. Madeline Kahn got me my job at the Upstairs at the Downstairs [the former cabaret].

ALS: How did you become friends with Madeline?

TOMLIN: I didn’t even know her at the time I first went to the Improv [the legendary Hell’s Kitchen comedy club]. When I first went to the Improv, I had to get someone to vouch for me. Every comic had to have someone to vouch for them. I had gotten friendly with a couple of comics who went there … I don’t know how. Maybe we went to see Ayn Rand speak or something. Anyway they vouched for me, so then I put on a blue velvet cut-on-the-bias halter dress, a kind of ratty white fox fur, which looked good at night, and I had ankle-strap shoes, and all that stuff. And I took the subway uptown from Fifth Street, because I knew the limos were parked at the theaters between the time they dropped their passengers off and the time they’d leave the theater. I gave a driver probably five bucks and said, “Take me to the Improv, but you have to wait for me.”

ALS: Like a limo.

TOMLIN: Yeah. So I had to go on at a certain time, and I just browbeat everybody into letting me go on at, say, nine o’clock. The limo swept in front of the place, and all the people who were sitting at the window looked out, and the guy opens the door, I get out in that blue dress and white fox fur, and I sweep into the Improv, do ten minutes, and I sweep out, get in the car, and drive away.

ALS: Brilliant, brilliant.

TOMLIN: That kind of set me for the Improv.

ALS: And Madeline saw you?

TOMLIN: I don’t know if she saw me that night, but she saw me at the Improv at some point after that. I’d go over there whenever I wanted to work on something. And she saw me and sent me a note. She said, “Call Rod [Warren, the writer and producer] at the Upstairs. We need a new girl in the show.” Fannie Flagg was leaving; she was going to Candid Camera. And I got in the summer show that year, ’66 that was.

ALS: God bless Madeline Kahn.

TOMLIN: I know. She got me the job at the Upstairs, and Rod worked on my specials after that. I worked at the Upstairs that summer. I got an agent because they started seeing me at the Improv. I was going to be Wonder Woman—they were going to do a funny series about Wonder Woman. It was the summer of ’66 and the Vietnam War was heating up, and Diana Prince worked at the Pentagon, so they had to shelve that. And The Garry Moore Show was making a comeback at CBS, and they sent me up to meet with the writers. The writers asked me, “Do you do any impressions.” I was going over very badly and it was like someone visited me from heaven, like Jesus put his hand on my shoulder. I said, “If I could do one thing on television, I would do my barefoot tap dance.” I’d never done it; it just came out of my mouth! And I got back to the club that night, and my agent called me and said, “Can you do this barefoot tap dance?” I said, “Yeah, sure.” And I went home, unscrewed my taps off my tap shoes and double-taped them to my feet, and I went out in the foyer with my landlady who lived next door to me and said, “Mrs. Vallone, see if this is funny.” So the Garry Moore Show people say to me, “We want you to be the runner-up talent.” We were doing a sketch about a beauty pageant in ancient Rome. The girl on the show was going to twirl a flaming baton. And I was going to barefoot tap dance. And they were going to pay me $750. I looked like Carol Burnett at the time. I had short hair like hers. We shot that first show, and I thought it was old fashioned and terrible. The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour replaced Garry Moore midseason; that’s how retro they were. But my agent called me and said, “Sit down. They want you to be the girl on the show.” I said, “I’m not going down with that sinking ship.” “No, no. They know what’s wrong. They’re redoing the whole show.” So I agreed to do it. That Sunday we went to the hotel near the theater and sat down to read the new script, and it was exactly the same. They said they were going to change it, but I knew they couldn’t. How I was introduced to the public was that I’m sitting in my dressing room, saying, “Eyelashes perfect, lips succulent,” and then they say, “Five minutes, Ms. Tomlin.” And I say, “I’m ready,” and I put a gorilla head on. I said, “No, no, I can’t do that.”

ALS: That’s not funny.

TOMLIN: I said, “I can’t do that.” I fought every inch of the way. I lasted three shows, and they got rid of me. So I thought, “Well, I had my chance and it’s over. I was on network television.” I went back to market research typing.

ALS: So how did it change?

TOMLIN: I had done a Vicks VapoRub commercial, and I never heard anything. I went down to the mailbox one day on Fifth Street and it was bulging out. And I had, like, thousands of dollars in residuals, like about ten thousand dollars, something outrageous. I couldn’t believe it. I opened each envelope and it was, like, for $1,800. And I said, “Well, I guess I’m back in show business.”

ALS: You moved to L.A. in the summer of ’69 and started on Laugh-In later that year. Did Altman find you through Laugh-In?

TOMLIN: We had the same agent, Sam Cohn. He was also Meryl Streep’s agent. But he was kind of an artist himself. He kept Altman working. He was just devoted to Altman.

ALS: So Sam put you and Altman together?

TOMLIN: Yeah. Altman offered me the part in Nashville [1975] because Louise Fletcher had dropped out. She was going to play my part. And I didn’t know that until much later. That’s where the deaf storyline came in. [In Nashville, Tomlin’s character has two deaf children.]

ALS: Oh, because her parents were deaf.

TOMLIN: Right, and her then-husband was a producer who had produced Thieves Like Us [1974], and he and Altman had a falling out. So then Louise dropped out of Nashville, and I guess Bob needed somebody kind of in a hurry.

ALS: Come on, there must have been a quality he saw in you. I think you and Shelley Duvall were the two actresses he used the most.

TOMLIN: Shelley did quite a bit. I would have done more but I pulled out of Ready to Wear [1994]. I just wasn’t sure about Ready to Wear. I did have Edith Ann [Tomlin’s devilish five-and-a-half year old character]. I was trying to nurse Edith Ann along and get a series for her, which I never could get. So I kind of used that as a reason to get out of Ready to Wear. I wasn’t confident about it. I wish I’d done it now, because I lost Kansas City [1996]. If you pulled out on Altman, you sort of excommunicate yourself for a bit. I really only did four movies with him.

ALS: But you’re so associated with him.

TOMLIN: Also, I did Bob Benton’s The Late Show [1977], which Bob Altman produced. I was a part of the family.

ALS: I just saw Nashville at MoMA; they had a screening of a new print of it. The thing I know he was attracted to, which I’m attracted to when I look at you, is your ability to be still. Only you and Richard [Pryor] could just be quiet and let the audience take it in. It’s such a gift. Your ability to be still in Nashville is so profound. After your character describes those beautiful boys who have been paralyzed in motorcycle accidents, we don’t know how it’s going to turn out. And just to be quiet after that is such an incredible moment … Altman was no dummy.

TOMLIN: Oh my God. Bob? He was great.

ALS: I remember you once saying in an interview that the crew wasn’t so nice to you.

TOMLIN: I said, “I have to go on and try to get another job. You guys will just go on to another film. It’s nothing to you.” This was only my second movie. It was ’76 [during the filming of The Late Show]. Everybody kind of remembered that comment as if I was being haughty, and I wasn’t.

ALS: What was different for you between stage and screen?

TOMLIN: Nothing is that different. I don’t know what’s different about it. You just put what you have to put out.

ALS: Tell me about our favorite person, Jane Wagner. She had written, of course, the film that had such a big effect on me, J.T., which you saw as well. And you were doing an album of Edith Ann. So you contacted her because you wanted some writing for Edith Ann.

TOMLIN: Yeah, I knew about Jane, mutual friends, our friend [the actress] Betty Beaird introduced her to me in New York; it was ’71. I had an album coming out on Polydor, and they had a little party for me. I had met Jane earlier in the day and just was smitten with her, totally. I stayed at the Sherry-Netherland. I was wearing cashmere turtlenecks and long skirts on stage in those days. We went down the street, to Reuben’s, and had lunch. And I was just desperate to connect with her. And she didn’t seem terribly interested in me. I had to leave to go someplace, and I kissed her full on the mouth. I said goodbye to her, and I just wanted her to respond to me in some way. So then we were having a party that night. I called Betty and said, “Try to get her to come to the party.” She came and she had on go-go boots. And she had hot pants on. [laughs]

ALS: And gorgeous, of course.

TOMLIN: So lovely. And quiet, so quiet. I had to leave for Chicago soon after; I had a date. She had a little backpack on, and I put my phone number in her backpack. I took the train to Chicago. I hit Chicago, and I got right on the plane and flew back to New York.

ALS: She was on your mind the whole trip.

TOMLIN: The whole time. And I flew right back to New York and called her up and said, “I’m in New York. I don’t have much time. I want to see you and get to know you,” And she allowed me access to her presence. [laughs] Anyway, so then I tried to entice her to come to California. I called and asked her to come out and produce the Edith Ann album. I told her how much I loved J.T., and eventually she sent me some papers with notations and scribbles and things like that at the last possible minute. And I said, “You’ve got to come out here and help me produce this.” Of course, I was living in a little shack at the beach in Malibu. It’s a very good neighborhood, but very poor circumstances. And she came.

ALS: And that was it. Was that very exciting for her to work on that?

TOMLIN: I don’t know if it was exciting. She never acted excited. But it was exciting to work with her.

ALS: What was it about her words, Lily, that made you feel so at home? I think her writing is so gorgeous. I always feel I can hear it in five seconds, what she’s written. Because it comes from the soul, in some deep way of understanding the soul.

TOMLIN: Yeah, well, we had this Southern history behind us, she’s from Tennessee, my parents are from Kentucky. I’d gone to Kentucky every summer growing up. And so I understood the culture. She understood the culture and sort of fled it. But it was just that melding, I couldn’t possibly do what she does, but I so got it. I could intuit when she started writing The Search [for Signs of Intelligent Life in the Universe, Wagner’s play, which Tomlin performed on Broadway in 1985; a film version was released in 1991]. I was head-over-heels enraptured. I didn’t know how she was going to do it, but I knew where she was headed.

ALS: She would show you drafts as she went along.

TOMLIN: Or she’d write a little something and send it to me when I was on the road, and I’d work on it. I put it into a show, like a part of something.

ALS: When you guys worked on Appearing Nitely, it was great. Those characters were so profound to me. But The Search was a different thing altogether, really.

TOMLIN: Yeah, well, she and I both wanted me to play in the theater so I could be legitimized and not have to leave town the next morning, from a one-nighter, you know?

ALS: To be in one place.

TOMLIN: I’d get a great review and I’d be gone, on to my next date. So I didn’t have time to get any real attention. So we named the show Appearing Nitely.

ALS: Appearing Nitely was extended for how long?

TOMLIN: They extended it twice.

ALS: I saved that Rolling Stone issue, for years and years, when you were on the cover for Appearing Nitely. One of the things that is so brilliant about it was that it was a way of working that you controlled. You’re not waiting for a film script.

TOMLIN: No, God. I always made stuff for myself to do. That’s Jane’s nature, too. And doing the street theater [When Appearing Nitely opened, Tomlin would appear as her character Mrs. Beasley and hand out coffee and donuts to fans in line], you do it for your fans. I don’t have fans that young anymore.

ALS: You don’t?

TOMLIN: Not really. Not enough to open a box office. Back then, kids would sleep overnight at the box office or even in the bitter cold.

ALS: Would you do that show again?

TOMLIN: Appearing Nitely? I haven’t even thought about it. I could.

ALS: Because that script wasn’t published, I always wanted to read Appearing Nitely. Maybe Jane will lend it to me.

TOMLIN: It was more of a compilation. And she just loosely wove it together. We ought to publish that. I use a lot of that material in the act I take around. I do Ms. Sweeney and I do Sister Boogie Woman.

ALS: Sister Boogie Woman is amazing. That takes a lot of energy, because the boogie gets in you. So that’s what you and Jane would do, this amazing thing of creating your own theater. Did you two produce The Search together?

TOMLIN: Yeah. I was sort of at my zenith of popularity. Well, maybe not.

ALS: Get ready, because Grandma and this series Grace and Frankie … Lily, I’m telling you, it’s a profound performance.

TOMLIN: I’ve got to tell Jane Fonda, because, she’s so insecure.

ALS: I know she is, that’s what’s so gorgeous about her, though. That’s what makes her a great actress—she just vibrates her strangeness. She knows I love her, but she’s a deeply weird woman. She radiates that. And it galvanizes you to her in such a profound way. And what you do is that you have your silence and you just stand there. And the combination of you two, it’s like watching magic. Please tell her that we had lunch today. I love Jane.

TOMLIN: I will. She gives it her all, always.

ALS: How was it playing Westbury?

TOMLIN: It was fun. I’m going to go to L.A. tomorrow. Then I’ll come back here for Tribeca.

ALS: I think we should try to work on publishing Appearing Nitely. Why not?

TOMLIN: I’d have to go back and look at everything. I’d have to look at Crystal and see if it’s up to date, the quadriplegic. [laughs] I’d have to look at the ’60s stuff and how much would it all play.

HILTON ALS HAS BEEN A STAFF WRITER AT THE NEW YORKER SINCE 1994, AND A THEATER CRITIC SINCE 2002.