NYFF

Filmmaker Radu Jude Takes Us Inside His Algorithm

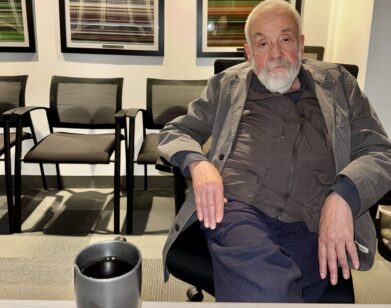

Radu Jude, photographed by Silviu Gheție.

“We must start and finish with the art of description,” Radu Jude exclaimed, citing Johann Wolfgang von Goethe on a Zoom call last week. Description is essential to the Romanian filmmaker’s body of work, in which one can find biting political critique in what are otherwise ordinary stories of everyday men and women. His two new features, Kontinental ‘25 and Dracula, both of which premiered at the New York Film Festival last week, are no exception. Here, narratives of corruption and freedom, barbarity and bureaucracy, comedy and catastrophe emerge from Jude’s keen sense of tragicomedy.

Jude considers this something of a national inheritance. As he tells it, Romania’s transition from dictatorship to neoliberal chaos produced the conditions for resistance, amusement, or both. If you can’t oppose power directly, you might as well joke about it. It’s a long-standing tradition, he explains, that has carried from 19th-century satirist Caragiale to Eugene Ionesco and onto Jude’s own wry, formally adventurous cinema, where history’s contradictions are laid bare. The standout of the two features, Kontinental ‘25, follows a woman wracked with guilt after displacing a tenant who hangs themselves from a heater just shortly after being evicted. Dracula, meanwhile, is a three-hour meditation on myth, cultural memory, and A.I. In conversation last week, we talked about our changing relationship to images, the descent of the American regime, and the peasants and pornstars that populate his algorithm.

———

SANDSTROM: Nice to meet you. Where are you right now?

JUDE: I’m in Bucharest.

SANDSTROM: Very cool.

JUDE: Where it was heavily raining all day and with a wind that fell down trees and all that.

SANDSTROM: You didn’t come to New York for the film festival, right?

JUDE: Unfortunately I couldn’t, because I am close to shooting a new film in just a few days. Also at the same time, I had a retrospective organized by Centre Pompidou in France, which I accepted long before New York Film Festival.

SANDSTROM: You’re working on a new film already?

JUDE: Well, when you don’t have talent, you have to do it. John Cage is one of my heroes and he said that you have to be able to create without inspiration. That’s my principle.

SANDSTROM: I like that. Well, I got to see both movies at the festival.

JUDE: I apologize.

SANDSTROM: I didn’t know Dracula would be three hours. I loved Do Not Expect Too Much from the End of the World, but I knew that it was three hours going in, so I was ready for it. I think you have to be prepared.

Still from Kontinental ’25. Courtesy of 1-2 Special.

JUDE: I agree. It’s like taking a book and you wouldn’t know how many pages it is.

SANDSTROM: But Don’t Expect Too Much from the End of the World, I loved it. That end shot, the 30-minute single take, was just one of my favorite things I’ve seen.

JUDE: Well, I was better when I was younger.

SANDSTROM: The new ones were great too, so let’s talk about them. With Kontinental ‘25, where did the idea come from, and why did you want to tell that story in particular?

JUDE: Well, that’s not a question. It’s two, actually.

SANDSTROM: Sorry.

JUDE: No, I’m joking. I don’t know where to begin actually, because so many false starts appeared. There was a moment when I saw it on a small website in 2010, a woman who felt guilty of evicting someone. What struck me was that people around her, her husband and also the reporter, tried to comfort her, telling her, “No, no, it’s not your fault.” So all of a sudden, I felt this tension; a kind of tragically funny situation. But I forgot about it, and came back again. And from that moment until now, which is like 15 years, the situation of economic inequalities, of gentrification, of real estate development with no rules whatsoever, all these things grew. I started to teach in Cluj, in a city in Transylvania, where this is happening even more so somehow. So all of a sudden, that old story felt proper to make in this context. But still I didn’t know how to structure it. And then by accident, I was reading a theoretical text about Rossellini of a great Romanian critic, Andrei Gorzo. So I watched again Europe ’51 by Roberto Rossellini and immediately felt that if I restructured the films in such a way to enter a dialogue with the themes, all of a sudden I can do it. So from there, everything went fast.

SANDSTROM: There’s this specific detail of him hanging himself from the radiator. Why did you choose that?

JUDE: Oh, that detail comes from, it’s really… my god. It’s really, really heavy raining outside. It’s just noise…

Still from Kontinental ’25. Courtesy of 1-2 Special.

SANDSTROM: Atmospheric?

JUDE: Yeah. That detail came from a situation I heard about some time ago. My first reaction was kind of bewilderment and not understanding, because when someone says “he hanged himself from the radiator,” what does it mean? It seems you hang from something which is high, not from something which is low. And I like that she’s forced to tell the story, again and again, not only because she felt this need to, but also because there’s a misunderstanding of the technicalities.

SANDSTROM: Yes. Which then becomes quite funny.

JUDE: Yeah, I think so. At some point I read about Goethe saying, “We must start and finish with the art of description.” And I believe it’s important to describe. In the case of this film, maybe there is some absurdity, but there’s always some absurdity that comes from real histories or real life. It has a lot to do with our civilization in Romania, with the change from a totalitarian brutal dictatorship to a more chaotic and open neoliberal society, where corruption mixes with certain freedoms, mixes with corporate interest. This split between Western civilization and Russian barbarity, all these tensions are mixed together and create situations that really, really seem absurd when I tell them to other people, though they happen every day.

That’s one thing. The other deals with the way our culture deals with things. One of our greatest writers, [Ion Luca] Caragiale, was a 19th century writer who really had an eye for absurdity. Actually Eugène Ionesco, when he created the Theater of the Absurd with Beckett, was very much influenced by this guy. And in Caragiale, there is a kind of sensitivity to absurd things in language, in real life, in politics, in history, in whatever. And I think that informed a specific Romanian perspective on things. In the last years of dictatorship, it was impossible to have a real resistance or people being against the regime in an open way. On the contrary, it was full of jokes about the regime. I remember we had a terrible earthquake in ’77 and a lot of people died. And this theater director said, “I felt Romania doesn’t have a chance, because a few hours after the earthquake where people were still under rubble, a joke already appeared.” For staircase, we have the word, “scara,” like for scale. So the joke was something like, “Are you taking the elevator or the Richter scale?”

Still from Kontinental ’25. Courtesy of 1-2 Special.

SANDSTROM: People always say Americans don’t have that kind of humor relative to Brits and Europeans. Maybe Trump will induce some kind of new national humor.

JUDE: But he’s the one who has a trashy, cynical sense of humor.

SANDSTROM: He does. I wanted to know more about your relationship with the U.S., and what you make of it politically.

JUDE: It’s so complex that I don’t think that one can have only a unilateral perspective on it. On one hand, there’s so many great things coming from the U.S. and at the same time so many bad things. But politically speaking, after the 1989 revolution since our country was on the periphery, it was always told by more “enlightened” people that we need a model. People say, “Look at the U.S., they always were a democracy. This is what we have to follow.” That or Western Europe. And now all of a sudden, you cannot offer a model. Nowadays, going West, towards American values, American society, American politics, means exactly the opposite. It seems really, really toxic and really scary, this fact that you don’t have a model anymore. Who’s the model now? You can say Germany, but Germany is very close to having AfD [Alternative for Germany] in power, or you can say U.K., but they had Brexit. You have Trump there, you have Putin there, and it’s almost there in France. So that creates a very sad perspective, you see. You know better there because I don’t live there. I never set foot in the United States by the way.

SANDSTROM: Oh, you’ve never been to the States?

JUDE: No, I never been. But what is somehow striking is the fact that there’s a kind of silence on things that should have been a scandal, or an opposition or people in the street. When the first measures were set by Trump I said, “Oh, Americans, the next day it’ll be 10 million in the street and they will never go back.” And on the contrary, it’s such silence.

SANDSTROM: Yeah. The police force and military are too strong to actually protest meaningfully and I feel we’ve sort of developed this immunity to the shock. Trump has actually been posting A.I. videos with misleading policies, or talking about things that don’t exist. So I want to talk about A.I. slop videos. What do you make of it? Sometimes I’m sat there watching some stupid fake car accident and I just think, “What the fuck am I doing with my time?”

Still from Kontinental ’25. Courtesy of 1-2 Special.

Still from Kontinental ’25. Courtesy of 1-2 Special.

JUDE: Well, my interest in this mostly comes from my interest in images. I try not to make any hierarchy. I’m not saying that if I compare a small idiotic A.I. video with a masterpiece of cinema, with Citizen Kane, that they are the same. But from a certain perspective, they are the same. They belong to the empire of images and are all parts of the same house in a way. It gives me the curiosity to work with all what’s new and also everything that’s also old. I made films on 16 millimeter black and white, to try and see how it works. It’s the same with what is around, with TikTok videos, with Instagram, with Reels, with A.I. I still think A.I. images are such a shocking new thing that it’s still problematic for everybody to have a definite opinion or a definite interpretation of them. Also, this puts us in crisis, not only for cinema as an art but our relationship with images. If I open my computer and see a photograph, I cannot say if it’s A.I. generated or a real photo. This creates a world where our relation with images changes forever. I don’t think we have all the tools, philosophical or aesthetic tools, to really understand them.

SANDSTROM: Do you watch a lot of TikTok?

JUDE: Well, not a lot. I mean, I watch maybe 15 minutes a day.

SANDSTROM: Oh, that’s very controlled. What does it show you? What’s your algorithm?

JUDE: Well, it shows me a lot of Romanian things. A lot of peasants and a lot of horny women if I open it randomly.

SANDSTROM: Did you say peasants?

JUDE: Yeah.

SANDSTROM: Oh.

JUDE: That’s it. Or this is some people who are doing a kind of genre.

SANDSTROM: Yours is really fun.

JUDE: Yeah, That’s a guy

SANDSTROM: Who’s that?

JUDE: A guy. He’s making videos with food.

SANDSTROM: Yeah. I like to watch people eat.

JUDE: The horny women.

SANDSTROM: Oh, no.

JUDE: And the text is really, really dirty.

SANDSTROM: What does it say? Can you translate for me?

JUDE: Well, it’s something about the melon, but just for the rhyme, because it rhymes. He said, “I would stick my cock into you lady.”

SANDSTROM: Oh. no.

JUDE: “Until your clit will start shaking,” something like that.

SANDSTROM: I like the cat. Very cute.

JUDE: People are doing these kind of things, isn’t it great creativity in that?

SANDSTROM: I don’t know what it is yet. It’s something.

JUDE: It’s something.