XXX

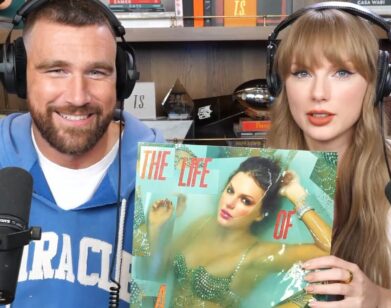

“Fucking Is a Form of Knowledge”: Kay Gabriel, in Conversation with Hari Nef

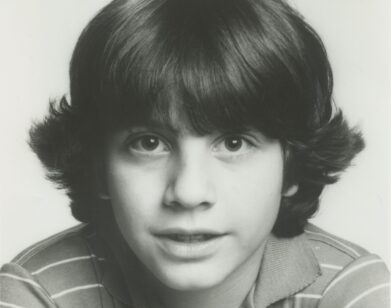

Kay Gabriel has a rare gift for turning the stuff of life into literature. As editorial director of The Poetry Project and author of Kissing Other People or the House of Fame, she’s made a practice of capturing community—its gossip, charms, and politics—on the page. Her new book Perverts, out this week, is no different, unfolding as a dreamlike portrait of queer New York stitched together from nightlife, activism and, of course, sex. “I wanted to draw on the collective insight,” she explains, “the humor, wit, and cuntiness that happens when a lot of people put their minds together.” To mark the occasion, she got together last month with actor, writer, model and friend Hari Nef to talk coming of age, club culture, and why “fucking is a form of knowledge.”—OLAMIDE OYENUSI

———

HARI NEF: I’m so happy for you.

KAY GABRIEL: It feels amazing.

NEF: This is such an amazing time for you. You have love in your life. You have a husband. And you are releasing your new epic poem, Perverts. I was so excited to read Perverts because it almost felt like you beat everyone to the finish line in the smartest, most roundabout way. I feel like we’re all waiting for that other shoe to drop like, “All right, who’s going to write a book about us? Who’s going to create the encapsulation of whatever’s been happening in underground queer New York for the past five years?” And I also happen to know that there are film interpretations of the scene well on their way. I may or may not have participated in one of them.

GABRIEL: Work.

NEF: But what you did is you painted a picture exclusively of the people who populate the scene, your friends who do the things you do and go to the places you go. But you came at it from the subconscious—this collective dream. Tell me about that.

GABRIEL: Yeah, that’s such a beautiful and generous way to describe the project. I mean, in a way it does have the feeling that any kind of structured social organization has—one that has a principle that it’s trying to push or just a room that you enter where a lot of people know each other. It’s a book that has a lot of structured internal social dynamics. People are talking to each other. People are thinking about each other. People are putting words in each other’s mouths. And not everybody knows each other. Even though I’m a Frank O’Hara bitch—I enjoy gossip as much as the next person—the feeling that I didn’t want people to come away with was, “Oh, these people think they’re so cool, they’re so sophisticated. I can’t be a part of it.” This is where, I think, the dreams come in. I wanted to just draw on the collective insight—the humor, wit, and cuntiness that happens when a lot of people put their minds together and decide to do something together. A party is one way that that structures itself. And that’s what’s really interesting to me—this oblique exercise in collective capacity, collective language, assembling something together that allows people to see something that one person could never accomplish on their own. And I get to have the really fun role of allowing people to talk to each other through the medium of the book.

NEF: What did they gain from you as their connector?

GABRIEL: Great question. I mean, something that’s been interesting about the experiment is that people don’t remember what they told me. They only encounter it again in the book. So people actually recognize themselves in a different way or recognize themselves because somebody else remembered it, which is just what it means to live in a society where you come to know yourself through others’ perceptions of you. That kind of theory of mind is one way that people have a particular brilliance, because if you live in a world where you always have to develop an understanding of what other people think about you before an encounter happens, you become, in a very everyday way, a genius at other people’s thoughts and perceptions. That comes up in the book.

NEF: But I feel like what feels so unexpected and refreshing about this is that you can’t pose in a dream; you can’t modulate the way you look or feel. And that’s why it feels to me more complete than any kind of anthropological snapshot you might write about yourself and your friends doing these things at this time. And these things—for the readers at home—are organizing, nightlife, and making art.

GABRIEL: Yeah, absolutely.

NEF: More or less, that’s what we all do.

GABRIEL: And then I’ll say a good helping of fucking in the book.

NEF: Oh, yeah. Organizing, nightlife, fucking, and making art. Rank them from least important to most important.

GABRIEL: Organizing is number one.

NEF: Period.

GABRIEL: Fucking is number two. Nightlife, and then making art. I think nightlife for queer people is more important. Seva [Granik] believes that nightlife pushes queer culture and therefore culture in general forward. I basically believe that’s true. It’s where we meet each other or come to know each other. We deepen our relationships through it, and that is the essential function. People get really fancy about what the social and political function of queer nightlife is, and it’s literally just that we meet each other.

NEF: Another canto in the book is basically a diss track to Larry Kramer entitled “Trannies.” What do you think about Faggots? I started reading it two weeks ago. I read what you wrote about it, and I read the introduction of the book. I mean, no one is denying that this is a work of pessimism and scolding, and he was very validated by history because of what happened in the gay community, with the AIDS crisis directly after he published it. But I’ve heard people talk about the moment that we’re in now—with PrEP and frameworks for non-monogamy and loosening boundaries around gender and sexuality—as a restoration of what gay culture and gay sex was.

GABRIEL: I mean, let’s think about that for a second, because I think this is such a telling mistake. I don’t know if I believe it. Sometimes people have this very interesting, very telling mistake when they talk about Faggots and they say that Kramer wrote it in the ’80s with knowledge of the AIDS crisis. That’s not true; it was published in 1978.

NEF: Yeah.

GABRIEL: It’s an interesting mistake because it seems to justify his moralism in retrospect like, “Oh, well look where all this promiscuity got us.” And we know that’s not a good way to think about the AIDS crisis. It’s not actually like unprotected sex and drug use were responsible for mass death. The intentional neglect of both the market and the state at every level—federal, state, municipal, and internationally as well—were responsible for mass death. So the easy way out is to say, “Oh, you faggots are wrong. You trannies are wrong. You are making the wrong choices because of the unprotected sex you’re having and the drug use that you are indulging in. And if I scold you enough about your individual choices, I will affect the problem.”

NEF: But what is the problem?

GABRIEL: The problem is a society that puts profit over people and the planet. And the problem is factions entrenched in existing power structures who do not currently experience a crisis in consigning us and other people to premature death. I think there’s an interesting relationship to moralism and how we talk about our excess and pleasure, how we talk about the class society that makes them possible, how we put all of these things together and the friction that we get out of it. And honestly, the poem literally started as a joke. “What if it was Trannies by Larry Kramer?” And then that became an extended, almost speculative fantasy about if there was a developed class society of transsexuals in the 1970s in the same way as for gay men when Kramer was writing Faggots. It’s not like I’m just lampooning Kramer. If I was just saying, “Larry Kramer, fuck you,” that poem could have been four words long.

NEF: No, you clearly live. And you’re drawing a line between the way gay, faggot identity has gestated, developed, progressed, and codified itself and the way we’re doing that for tranny in real time. And I feel like the departure from prose to poetry contains that. And obviously there’s a lot that divides us and there’s a lot that unites us. And I feel like you are paving the way and you are creating not a map, not a guide, but making an offering and looking communally. You’re not coming from an individual moral standpoint. Dreams don’t lie. Neither do hard dicks. Those are the two things that will never lie.

GABRIEL: Oh, period. I mean, I’ll say it again: Fucking is a form of knowledge in the book. And sister, we are scientists.

NEF: Damn, bitch. We live like this.

GABRIEL: Obviously, I run a party called “Faggots are Women.” I’m never going to be one of these girls who are like, “Fuck you, faggots. Fuck you, gay guys. It’s so circuit-y in here.” Sometimes I don’t want to be at the 95%-gay-guy party. But also, sometimes it’s a vibe. And the thing that I want other people to understand is gay guys’ social wisdom is profound, including in moments where we think it doesn’t include us. Gay guys have a profound social wisdom about how you conduct yourself in a big scene where some people in there may threaten you, but you actually all have to get along and wrestle with your own sense of competitiveness and stare that in the face and get over it. Because the girl on the other end who’s making you feel bad is not actually your enemy. And that’s something that dolls can learn from in a big way—gay guys who have gotten over gay guy competition. Gay guys who have learned to just be really sweet to people who they don’t really give the time of day to. And gay guy sass and gay guy nastiness, I mean, all of that—

NEF: The Velvet Rage. And I don’t know about you, but I feel like early on in college when I was starting the journey to where I am now, it was a quick fix for me to be very homophobic in that way because I felt like I had to distance myself from this culture of gay masculinity that was so close in my rear-view mirror that I gagged. And I think that that’s a journey that all the girls have to go on.

GABRIEL: Yeah, absolutely.

NEF: The key thing that’s allowed what has happened in our world and in our city was the dolls finally getting it when it came to gay guys and, more importantly, gay guys finally getting it when it came to dolls. There just used to be fewer dolls—

GABRIEL: Right, fewer dolls in nightlife. And this is something that you really led the charge on. Seva talks about how when he was throwing parties, even until really recently, the phenomenon of the nightlife tranny was relatively rare, right?

NEF: True.

GABRIEL: Not non-existent, but nowhere like it is now.

NEF: Yeah. I mean, there was always a culture of stars, statements and legends and I was so fixated on them that I didn’t notice that the only trans people in the room were the hosts.

GABRIEL: Yeah, exactly.

NEF: I just wanted to be like them. I wanted to be like Amanda Lepore, like Sophia Lamar. I wanted to be a girl like that.

GABRIEL: Yeah, totally. This is something that I think Charlene [Incarnate] understands so profoundly—the need that a lot of people have to see each other through a highly charismatic transsexual.

NEF: What does she allow you to see? The proverbial you? Not the gay proverbial she, but the trans proverbial she.

GABRIEL: The trans proverbial she. I had this really emotional moment when I was watching her perform at Campout this year when I got to the stage and I saw how many people gathered for her. And it was one of the most profound moments of my experience there, just seeing all of these people see each other through her. She started with the synth at the beginning of the “Bad Romance” video. And then it turned into “The Bad Touch.” And then at the very end, she did eight bars of “Bad Romance.” But it was all we needed. Last year, her drag number was “Macarena.” And again, the genius five-dimensional chess level that Charlene’s mind is working on is going like, “Actually, you know what? The Macarena slaps.”

NEF : I’ve been thinking about the lyrics of the “Macarena” all summer. Did you also feel the siren call of techno when you were a child?

GABRIEL: Absolutely.

NEF: I was drawn in that very transsexual way to electronic music because I was like, “Oh, a body didn’t make this. I’m so into this.”

GABRIEL: Before you were a teenager, who was your diva?

NEF: Madonna.

GABRIEL: You really are a classic homosexual.

NEF: I am. I was going to the Warner Brothers store, which existed at that time, to buy Batman memorabilia and seeing her on the giant screen doing a cowboy line dance in front of another screen. And I was like, “Why is this so pussy?” I think I bought Ray of Light in the Nantucket record store because of the cover.

GABRIEL: And that’s how they get us. That’s how they recruit.

NEF: My first concert was Shania Twain. My second one was the Cher Do You Believe? Tour. I didn’t ask to go. My mother took me. I didn’t know who Cher was.

GABRIEL: You were like, “Oh, she sounds like a man. I’m into it.” You didn’t stand a chance. I mean, to bring this back to Perverts for a second, it’s actually such a good detour. Part of the thinking behind the book has to do with people who at every stage of our consciousness are drawn to images, language, ways of acting that are socially prohibited. Of course, there are corny ways of celebrating this, but the determination that it requires to follow that voice and to not suppress it and to not go in the direction that coercion is forcing you to go. But what if we go, “This is how we make meaning out of our lives and out of our brains, our amazing minds, out of our profoundly amazingly idiotic language, out of the tissues that make up our bodies, out of the time that we have together.” It’s not just for trannies or faggots or gays or whoever. It’s also materials that we use to make social connection possible between other people, which I think has a lot to do with the coalition-building that is part of our task right now for making a livable life for everybody. And that’s also my TED Talk.

NEF: I think that is a fabulous place to say “period.”

GABRIEL: Period!

NEF: Because that was some real shit you just said.

GABRIEL: It was good.

NEF: I adore you, Kay Gabriel.

GABRIEL: I adore you, Hari Nef. Thank you so much for doing this.

NEF: Anytime.