Juliette Lewis and Erykah Badu on How to Break the Mold

Juliette Lewis is a force of nature. From the murderous protagonist she played in the cult freakout Natural Born Killers, to her Oscar-nominated performance in Martin Scorsese’s Cape Fear when she was just 18 years old, to the real-life rockstar she embodies as the leader of her band Juliette and the Licks, the 46-year-old performer has been tantalizing audiences with her raw, feral energy since the early ’90s. And while her personal life may have mellowed—late nights at the club have given way to early morning yoga classes—Lewis has retained her boundless energy, which still defines her performances. Her latest finds her acting opposite Mark Ruffalo in HBO’s I Know This Much Is True, playing, as she describes it, “a little hurricane from the world of academia.” But although she’s found balance in her personal life, as Lewis tells the singer, producer, and actor Erykah Badu, there’s nothing wrong with a little turbulence now and again. —ERNEST MACIAS

———

JULIETTE LEWIS: I don’t know how to do this, because what I really want to do is ask you about you, but… I’ll try to be a passenger.

ERYKAH BADU: Today I am the designated driver. You already know this: I’m a huge fan. I reached out to you on Instagram a few years back. I was just so hyper-impressed with the way that you manage through the shit that we have to get through. I appreciate that from a human being.

LEWIS: I want to say thank you. It’s wild when you see—I don’t know the language for it, but maybe kindred people that you revere. You’re like, “That’s a light. That’s a beacon in the sky.” I’ve always felt that about you and your unapologetic stance, the soul power of who you are. So, what I’m trying to say is back atcha.

BADU: Here’s the most obvious question a girl would ask another girl: Do you remember when you got your first period?

LEWIS: [Laughs] I was 12 and a half.

BADU: That’s early. I think I was about that age, maybe 13. How did it feel?

LEWIS: Well, I grew up in the Valley. I spent my formative teen years in Tarzana. My mom put me in school a year early and lied about my age. I think it was because she couldn’t afford a babysitter. I was hanging out with older kids, just a year older or two years older, but that can make a huge difference. I had friends who were getting their periods. I remember wanting to get it so I could complain about it, so I could seem mature.

BADU: You were practicing.

LEWIS: Exactly, I was practicing being a bigger person and not a kid. It’s so weird when we’re self-taught. My parents were both artists and probably gave me a little too much freedom, so I was taught by other kids. It’s my friends who taught me young womanhood, I guess.

BADU: My thing was different. I’m from the South, where anything that happened to a woman was to be pushed under the table. Nobody explained anything to me. It was kind of assumed that I would figure it out. I hid it for a year because I didn’t even want to deal with the questions. I was just so immature, like a child, and it was horrifying for me for that first year. I asked you that because that’s our first real responsibility in life as women. How we see ourselves as women kind of unfolds out of that. When you said your parents are artists, what did they do?

LEWIS: My mom is a graphic artist and her imagination is kind of fantastical. She’ll tell a story through rose-colored glasses. She was an only child, and when she was little she drew very detailed houses with cobblestone paths and trees and birds and little kids. She’s a mom of six kids and she probably would have had her own career had she chosen that. She went to Cooper Union in New York. My dad was a character actor who gained success when he was middle-aged. He did a million different jobs before that. But when his kids came into the picture, he was a working actor. I think when I say artists, what I mean is that they believed the creative mind is something to be nurtured and explored rather than treated as insignificant or a hobby.

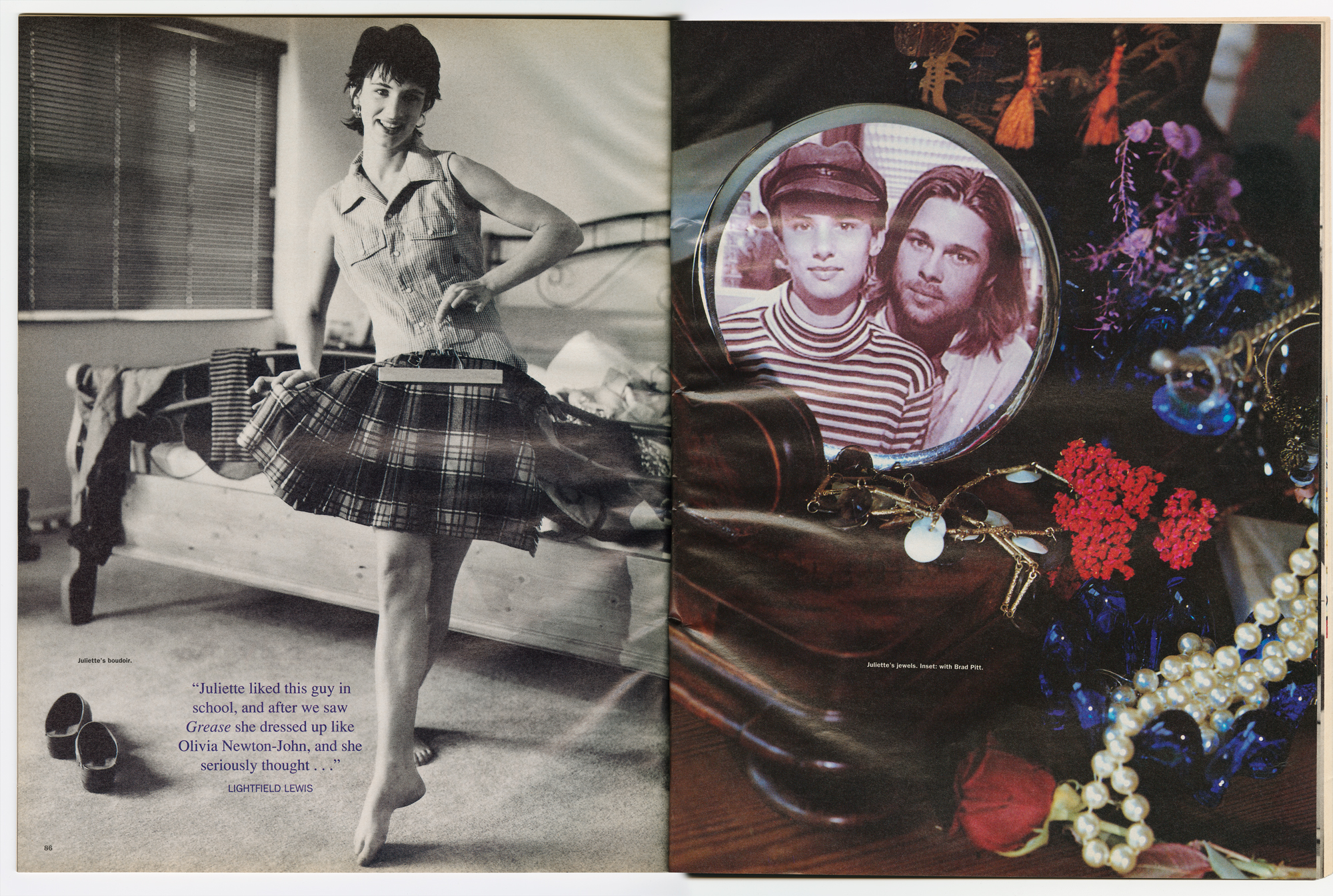

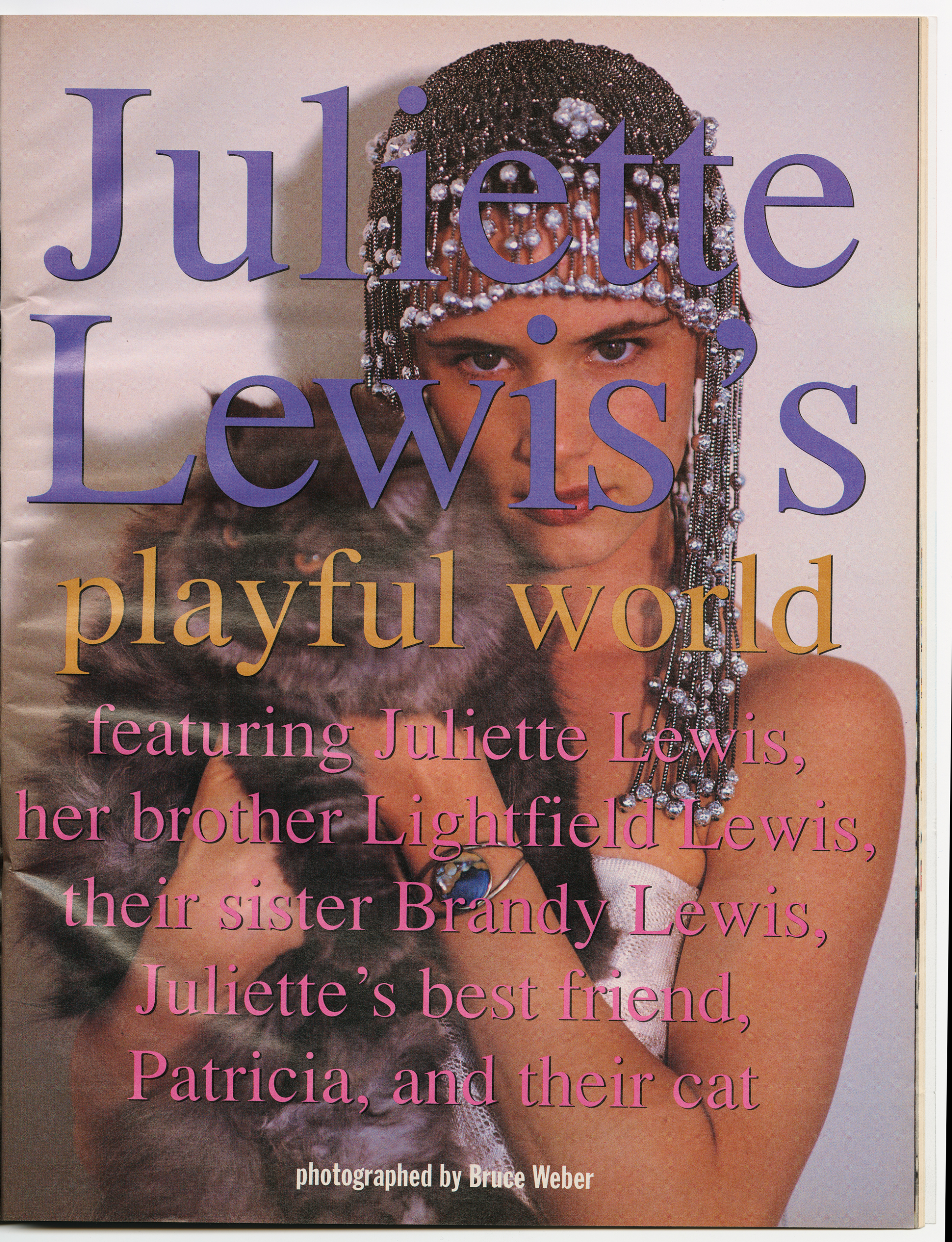

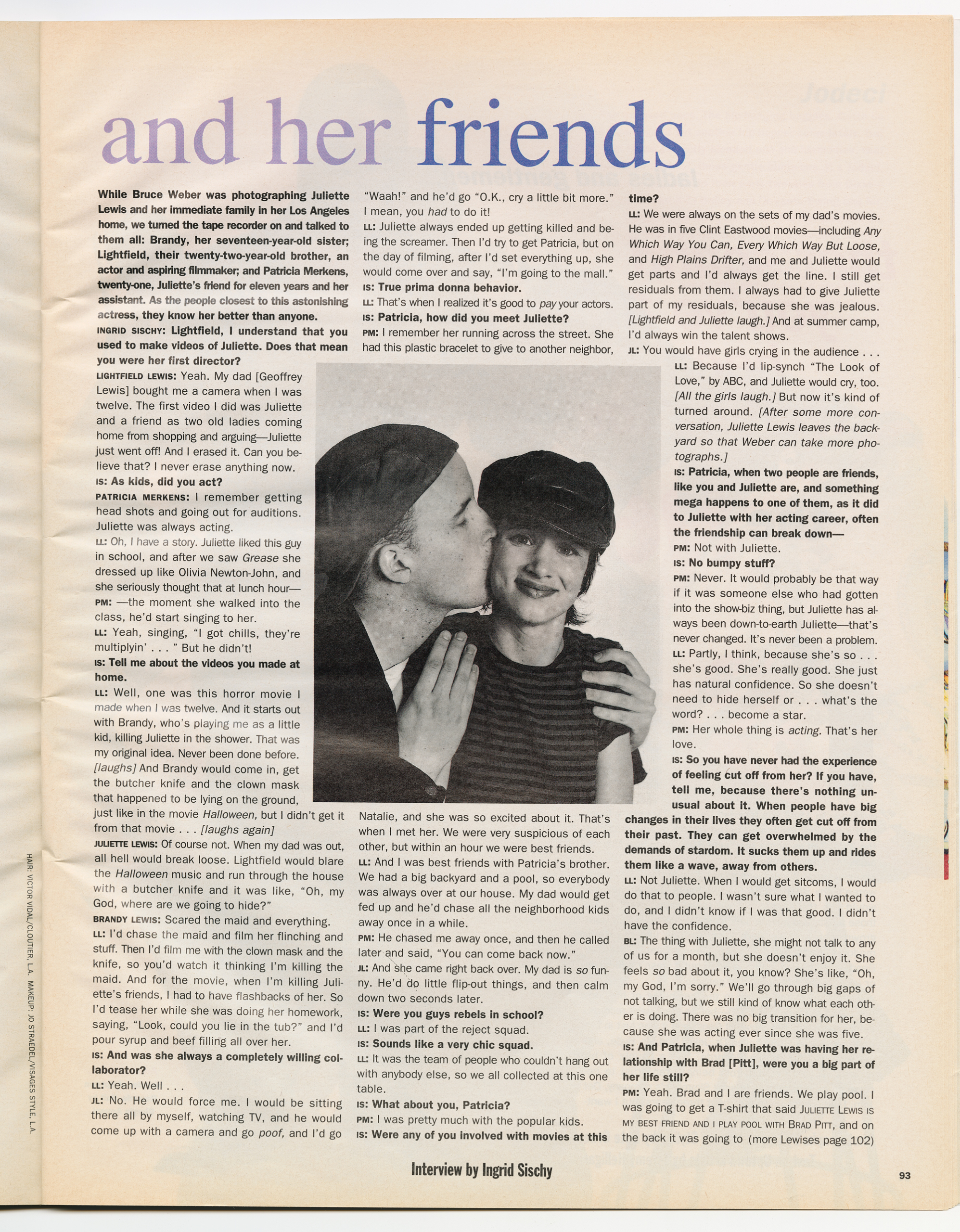

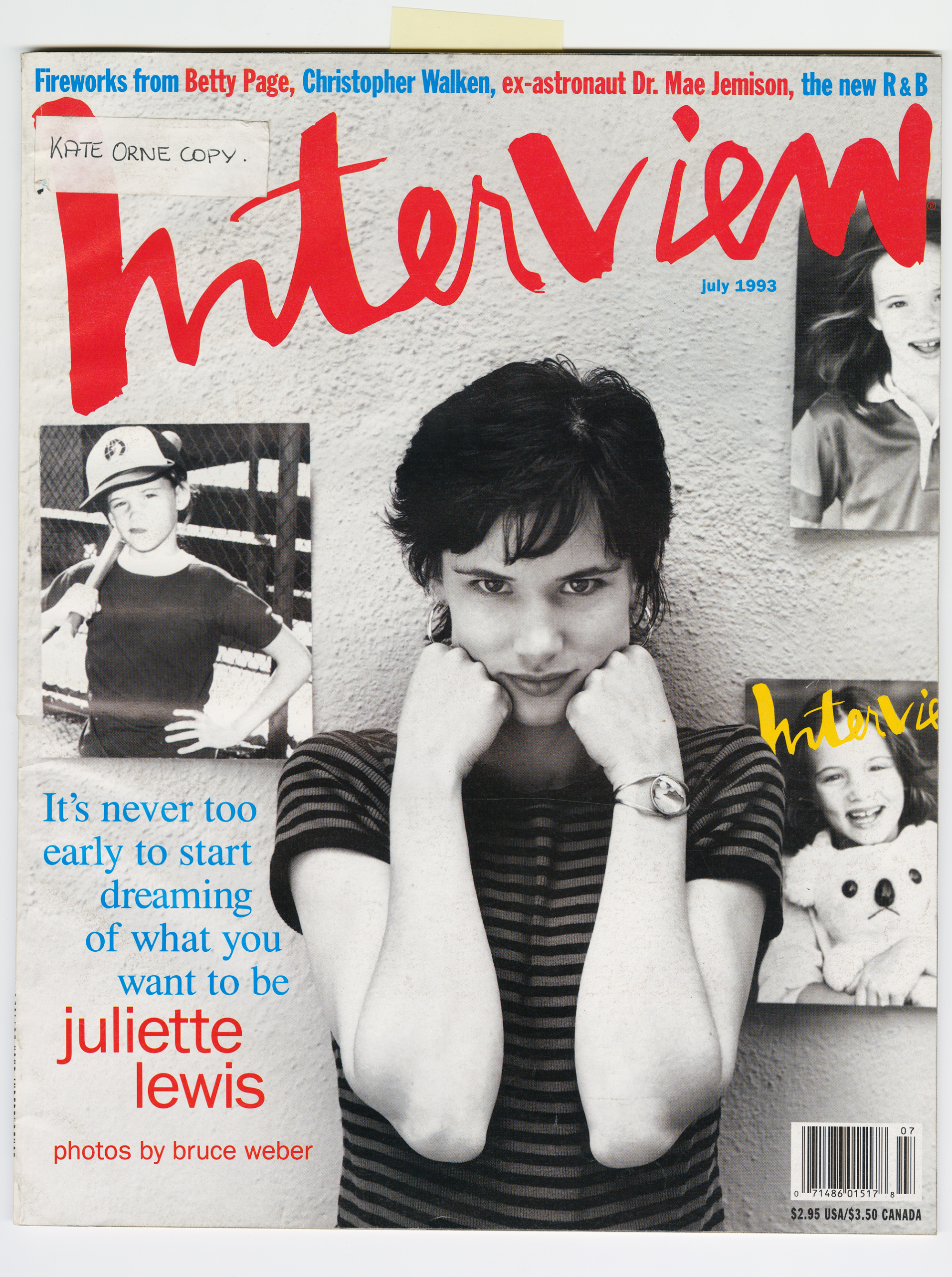

Juliette Lewis photographed for the July 1993 issue by Bruce Weber.

BADU: My parents were not artists, although my mom was very creative. I wasn’t raised by a dad but I was raised by a mom and two grandmothers. One of the grandmothers could sing and she bought me my first piano. My mother, again being raised in the South, was very fixed in her understanding of things. She did give me creative freedom but I didn’t get the understanding that comes from being the child of an artist.

LEWIS: When you say fixed understanding, do you mean about how to survive and make money to care for yourself?

BADU: Even more basic than that. “When you’re born into the world, you’re born into a certain tribe and this is what we do. We go to church. We speak like this.” Everything was kind of fixed for me. How I dressed, how I wore my hair. How long the dress would be.

LEWIS: This explains a lot about how you consistently break the mold. My parents were like, “Life’s all about the search, so keep searching.” Even with god. I remember in junior high, doing that trip where you’re like, “What if there was no Earth? What if there were no sky?” Having an existential moment. I asked my dad, “Do you believe in god?” And he said, “Yes, I believe in a supreme being.” He was basically saying, “You can believe in believing.” That’s been my entire modus operandi that got me into good things and out of bad things—the power of belief. I’m really pro whatever people need to feel bigger and brighter. That’s their own trip and I’m all for it.

BADU: So your parents were basically John and Yoko.

LEWIS: Well, I wouldn’t go that far. They were also not together. They had struggles of their own. Later in life, you start to think, “Who were those people that I grew up with?” Both my parents had several marriages, so there was a lot of adjusting.

BADU: But if it’s about searching, then failure doesn’t really exist. I think that’s a beautiful way to start your life. When you asked me to do this, I first went down a rabbit hole of just looking for interesting questions to ask. I looked through a lot of your interviews and you had already talked about so many things. One interesting thing to me was that in an interview you talked casually about challenging yourself and doing things outside of your comfort zone. I wanted to know more about that and how that plays a part in your decision-making?

LEWIS: It’s so important. As a creative, there’s life and finding balance within it—mental, physical, and spiritual. Creatively, in all the industries of the arts—yours, mine, the collective—there can be this set path. I always want to break formula and I just lucked out with I Know This Much Is True, because the director, Derek Cianfrance, and the star, Mark Ruffalo, the way they worked on this series was all about breaking the language of film, like action and cut—talk about being uncomfortable! I have all this experience, but certain parts are challenging because I don’t know how I’m going to manifest this personality. It’s so weird that even with experience I still don’t know if I can do it. I mean, those are the best parts or the best projects. When I started making music, I wanted to embrace the discomfort. I’m usually up for experiences where my head says, “Well, maybe there’s something in this that I can walk away from.” And there usually is, whether it’s a social experience or artistically.

BADU: I love to challenge myself, too, and just kind of see what I’m made of. It’s important to me because I don’t like to get stuck in any one place. Do you have any triggers that make you feel like you’re stuck?

LEWIS: Well, you’re being so lovely to interview me, but I’m thinking of all the things that I saw of yours, as a fan, and why I thought you and I would be an interesting pairing. When you first came on the scene, when I saw you, you were so you. You’re like nobody else. That’s so exciting. To me, comfort and complacency is the death of an artist. It means you’re asleep. There are two things that the outside world will tell you: what to be and what to think. The industry sells you on all this shit as a woman, as an artist. I try to break that up to be free-thinking. But I don’t know what the question was…

BADU: It mimics depression when I’m static. I did this thing one time, Ju, where I went out and did this vision quest. I did it with Native Americans in upstate New York. When you go up the hill, they call it “going up the hill.” You go up there for four days and four nights with no food or water, and you just kind of live in a tent. There’s a ritual you do before where you make these prayer flags: yellow, red, black, and white, 140 of each color, then you take them with you and you put them around this campsite that you set up for yourself. You’re separated from everyone else by a huge distance. You’re just out there for four days and four nights with no food, no substances, nothing. You kind of see what you’re made of. Your mind is doing all this stuff. Have you ever done any plant medicines or any of those types of rituals, because you’re a musician as well, so when you do find yourself static-like we were saying, what kind of things do you do to kind of say, “Okay. Who the fuck are you?”

LEWIS: Man, there’s some part of me that talks a big game, but even though I haven’t done it, I love the concept of what you’re saying. I did a five-day retreat but I can’t say that I roughed it, except for the hikes we’d take. You learn about your machine. You learn about letting go of your thought pattern and the constant thinking that the mind does. That was a really profound, spiritual experience to me. Because I have drug addiction in my history and DNA, anything that has a—even if it’s a natural trip, I can’t—it’s not good for me. I used to get these deep experiences or I searched for them in my work, like, “It’s 3 a.m., I have to act like I just found my dad murdered.” I did this cowboy movie no one saw, and I had no idea how I was going to do it. I’d obviously never experienced it, and I don’t so much believe in academic training. I feel like acting is about channeling and imagination. Anyways, I can push myself to find out what I’m made of in those instances. In life, I want to be open to those things. When we are done with this interview, I want you to tell me anything that you thought was cool that you could share.

BADU: I think that’s a good segue. This has been a nightmare job, trying to interview somebody for a top interview magazine. But I think it’s a good segue into your roles, because acting for me is an escape. I grew up as an actor. I started in plays and it just came so naturally to me. It was just something that I did. It was second nature. One thing I noticed about you as an actor—a mover through your creative spaces, whether that’s on stage or as a singer or performing in front of a camera, which is so awkward, just crazy-ass shit, but you have to kind of block out everything else around you and get to that space. When I see you move through that space, the first thing I notice about people is the way they breathe. I know that people notice it, too, with you. The way you talk and breathe suggests that you are so comfortable in your space as that character. Is it something that you worked toward, or is it just part of how they made you, whoever they are?

LEWIS: Well, that’s interesting to hear, too, what people notice about your work. The first thing I think about as a person, even in this latest project, is their energy, their frequency. So this character I just played, she’s on the verge of a nervous breakdown, but you don’t know that. I have to think, “What does that feel like?” You’re wound real tight and you’re trying to do your job and everything. You’re kind of bluffing your way through the social veneer. Out of that comes the rhythm of phrasing or voice. So even right now, I have a slight nervous excitement and I’m trying to cap it. I play within their energy and where they’re at as a personality. Are they bored? Are they excited? Are they holding secrets? And then it’s also really physical.

BADU: Well, tell me about this character. How are you similar?

LEWIS: Wait, just as an aside. People always thought I was Southern growing up because of my laid-backness. Isn’t it true, Erykah, that you’re not super stone-y, although maybe people assumed this about you?

BADU: Stone-y?

LEWIS: Like smoking pot

BADU: Oh! I mean, I’m associated with it all the time, so I just roll with it. But I didn’t get into any heavy drugs or anything. The most I’ve done is plant medicine when I go and do spiritual things. I just feel high all the time. I just feel like I’m walking underwater all the time.

LEWIS: I heard you talking in some interview about how you were very clean and I just thought that was so cool because I think people, when they’re lazy, associate a certain vibe to drugs. Anyway, this project came my way and it’s a character named Nedra Frank, and I loved everything about her. She’s like a little hurricane from the world of academia and trying to prove herself as a professor in a male-dominated industry. It takes place 20 or 30 years ago and she has a real chip on her shoulder. That’s how she’s written. We improvised a lot, so you’re making stuff up in the moment. That’s very unusual in TV shows today because they’re usually mired down by time. So this was a really special awakening for me to go, “Oh. This is what this could be: exploration.” You can explore ideas—even the bad ones that your ego is judging as stupid. You’re trying to rip that ego apart because out of that sometimes the best freak choices are made. It’s a six-part series about really deep themes of mental illness, family, struggle, and life.

BADU: Can we talk about some stuff that you’ve done in the past? I’ve always wondered, what are your favorite murders that you’ve committed in film?

LEWIS: You know what’s funny? I was so heavily associated with the one serial killer from Natural Born Killers. After that movie, I joked with Woody Harrelson, and later with George Clooney when I got to work with him for a while, that I was going to call my first EP Is She Crazy? But then I abandoned that because everybody I would end up working with would be like, “Wait, you’re not crazy.” But they’d tell me that their friends would always say “What’s she like? She’s crazy, right?”

BADU: You’ve had these intense moments between Brad Pitt and Woody Harrelson—a lot of sex symbols. And there was an intensity there between you, like chemistry and magic. And I see it when you’re on stage playing music, with the audience.

LEWIS: Thank you for saying that. Fifteen years ago, when I turned 30 and I put the band together, I had no experience. But being on stage was a holy place, you’re reaching transcendence. That’s the only way I can describe it. You transcend and you can’t even describe what’s happening. We get the feeling. There’s music that’s more intimate, like what you’re doing. You do all kinds of stuff, but I have insecurities as a vocalist. I’d like to be a better singer. So when I first started, I was like, “Fuck it, I’m just going to live within what my limitations are and not seek perfection at all.” For me, it’s about getting energy up on its feet. I was a limited songwriter. I’m a limited vocalist. I call myself an emotionalist because I can feel every instrument and feel what it is I’m singing about. I get sorrowful because I miss it so much. I got to get back to it. Right now we’re mourning the medium of the live show. I pray to have it happen again, even just for my friends because, holy shit, it’s the best feeling.

BADU: I guess I can’t describe it either, but it’s a therapy place. And then you got all these free fucking shrinks out there in the audience. What you’re doing is actually creating a lot of vortices in the room for people to emerge. It puts everybody in this one place. There’s one space above it all. When the satellite is really connected, when the signal is there, there’s that feeling that you were talking about, transcendence, and I’m super fucking happy for you that you could do that. You get that moment where it’s your planet and you are the conductor.

LEWIS: That journey with the live show, touring the world and playing tiny clubs that were falling apart and then graduating to bigger spaces, it was really just a love affair about kindred spirits. My band was so disciplined. I barely took Advil. I didn’t drink. I remember being up one time after having flown for a day and a half to Germany from Brazil. I lost my passport, so I had to go to Germany. Then we made it to Finland where the show was. I laid down on the floor in the hotel and all the voices were saying to me, “You need sleep. That’s the number-one thing. Your voice, it goes out quicker if you haven’t slept.” I remember think, “I have nothing.” But I had something. I had an audience, a sold-out show, and I had the power of belief. It ended up being one of the greatest shows because there’s no greater feeling than when you’ve come through something, and you’ve come through it together as a collective. Those moments are really special.

BADU: What’s your favorite candy?

LEWIS: Oh my god. There’s a teenage Juliette who ate garbage, and now there’s a healthy Juliette. But as a kid, I ate a Skor bar every day. Coffee in junior high every day. Now, I like everything coconut and my niece makes these coconut granola bars that you freeze that are the most delicious thing ever. What about you?

BADU: I’m not trying to win an award for being the best vegetarian or any of that kind of stuff, but I do like to take care of my body. I feel like I’m a Lamborghini, and I want to put Lamborghini gas in me. But I do have a guilty pleasure. If I see a Starburst on my kid’s dresser, I’ll just run my hand across the dresser and quietly collect that Starburst. And then I’ll go to the bathroom and eat it. I’ll look in the mirror and go, “What are you hiding from? Who’s going to get you for that?” The thing with my kids and health is, they all grew up vegetarian. They were all breastfed babies. They were all born in this bed I’m lying in right now. I gave them all of the tools that they needed—they started out vegan. No meat, dairy, and sugars. But now they are 11, 16, and 22, and they eat whatever they want. They don’t have to be little Erykahs or anything, but I do want them to know about the body and that it affects your attitude and your will power. I want to talk to you about your drug addictions, and the way you cope with things. Everyone has their own thing, their own mechanism. How do you find yourself and where are you finding yourself right now in COVID-19?

LEWIS: I have a few things I want to say. One is about what you just said about your world, as a caretaker, and as a mother. I have imperfect parents and I’m imperfect, we all are, but it’s really neat when your parents plant seeds and, yes, you can rebel against those, but then you come back to them because the seed was planted. What’s happening now is that all the solutions I use to keep myself sane are not accessible right now. That’s acupuncture, yoga class, exercise class, a craniosacral massage.

BADU: I love it.

LEWIS: Okay, you’ve done it! It is absolutely radical and wonderful. Anyway, I don’t have any of those things. So I have been struggling. But I’m glad we can walk outside. I like to think about what I do have and then try to unearth and readjust and find the resource in the tiny things. It’s an exercise I do. I go outside and look around for beauty and try to write things I’m grateful for. After this call, I’m going to go for a bike ride because we’re now allowed to go on the beaches.

BADU: You asked me earlier about being a druggie, or what’d you say? Stoner?

LEWIS: Stone-y!

BADU: From time to time, I’ve experimented with pot. I’m a Pisces. It’s kind of like what they say about us—Pisces people tend to be escape artists. We like to escape. I find myself wanting to do that all the time and finding ways to actually do that. I have an altar with candles and incense and things. Also had a pack of cigarettes on there. It has a little weed on it.

LEWIS: I’ve been smoking. The good news is being able to live more disciplined healthwise, I guess you can justify veering off for a time and giving yourself a break, especially in our current climate. I have a really good pack of girlfriends to go, “Hey, go easy on yourself.”

BADU: For me, in the experience of life on this planet, on this school called Earth, it seems like guilt is a harder thing to heal from than food and other substances. So I decided that if I’m going to do anything, I’m just going to do the shit and I’m going to be who I am—this is where I am at this time. I’m not trying to pretend like, “Oh my god, I shouldn’t,” I’m just going to be there. I think I get through whatever that is quicker without too many bruises.

LEWIS: I feel like that’s midlife. I really just got into that in the last few years. I could beat myself up to high heavens, like nobody else. That’s why, in a way, nobody could touch me. You could never shame me the way I could shame myself. It’s pretty vicious. You can go through a rough patch, but then why are you going to spend a year afterward reliving or beating yourself up for the rough patch?

BADU: I just remember right before this period that I’m in now, where I have no substances in my body whatsoever. I’m just walking around like this lightweight bad bitch all the time, you know what I mean? You’re talking about midlife—well, midlife for us means something totally different for men.

LEWIS: Totally different things.

BADU: I’ve heard you say that word maybe six times. Midlife. How do you define Juliette in midlife?

LEWIS: It’s been a huge transition of thoughts. First of all, it’s been about not being afraid to say, “This is where you’re at. You are not in your 20-year-old hustle as an artist.” I liked having a punk-rock spirit, but even that means something different now than it did at 20. So this started I think when I was 36, and I’m going to turn 47 in a month.

BADU: That’s a good damn age. I guess the number sounds good, huh? I like how it sounds. Forty-seven.

LEWIS: I think about death, and not just in an “it’s part of birth” way. I lost a few friends, a couple to cancer, and I go through “why” a lot. I don’t have any of that figured out. I just want to be brave about living. That’s all I want. I play a game with myself and I’ll leap into the future—I know you can get with this—and I’ll go, “Okay, well picture yourself at 70, looking back at where you are now. What would you think then?” There was a time when I thought I was running out of time, chasing the clock, and it breeds such anxiety.

BADU: Ain’t no clock. No clock. But it’s tougher for women. Have you ever noticed in an article that it’ll say, “Erykah Badu, 48, breaks a record and is a genius at skiing.” What’s 48 got to do with it? What does that message mean? What does it mean?

LEWIS: It’s the dumbest fucking projection. It’s so dumb. Ageism. I just love seeing people live in themselves in their power. I got to tour with Chrissie Hynde. I don’t know what age she is because she’s Chrissie Hynde. Artists help people think differently or broaden their horizons and limitations so that they can survive in this world, in all these restraints. These constraints and restraints, let’s not forget, are all so that you can be shopping. It’s all so that you can be sold and be the perfect consumer and follower. A long time ago I had to let go of interviews and their limited framing of women. I was thinking about this the other day, now that we have older women with relevance, they finally figured it out in some arenas that there’s viability in older people in general. I was thinking the other day about when I was nominated for an Independent Spirit Award for Cape Fear. I was introduced. The guy on the stage, he was some known comedian who’s no longer here. He introduced me as “The girl who sucked De Niro’s thumb.” Could you imagine? For a joke. To get a laugh. I was a young fucking artist. They would never have said that about a 20-year-old De Niro.

BADU: Right.

LEWIS: Things like that, the reducing of one’s work, the new ways to do it to women—you sexualize them, you talk about their looks, whether they want to fuck with their looks or use that or not, that’s part of their artistic or self-journey. Like even talking about Madonna. She can do whatever she wants.

BADU: I feel you. I have only one more question, and then I want you to go on your bike ride. Let me say that I’m honored that you would even ask me to do this. I hope I didn’t disappoint you or the magazine in any kind of way, but I wanted to ask you if you had one album and you were stranded on a desert island—

LEWIS: My mind is pinballing already.

BADU: If you had just one that you could play for eternity, which one would it be?

LEWIS: Pink Floyd’s The Dark Side of the Moon.

BADU: You better get out of my head, woman! Get out of my mind! This solidifies everything. Everything. As much as we are different, we have come back full circle because that’s the one I pick, every time. We are kindred spirits. This interview is over.