Mark Ruffalo and Philip Ettinger on Playing Four Versions of the Same Two Characters in I Know This Much Is True

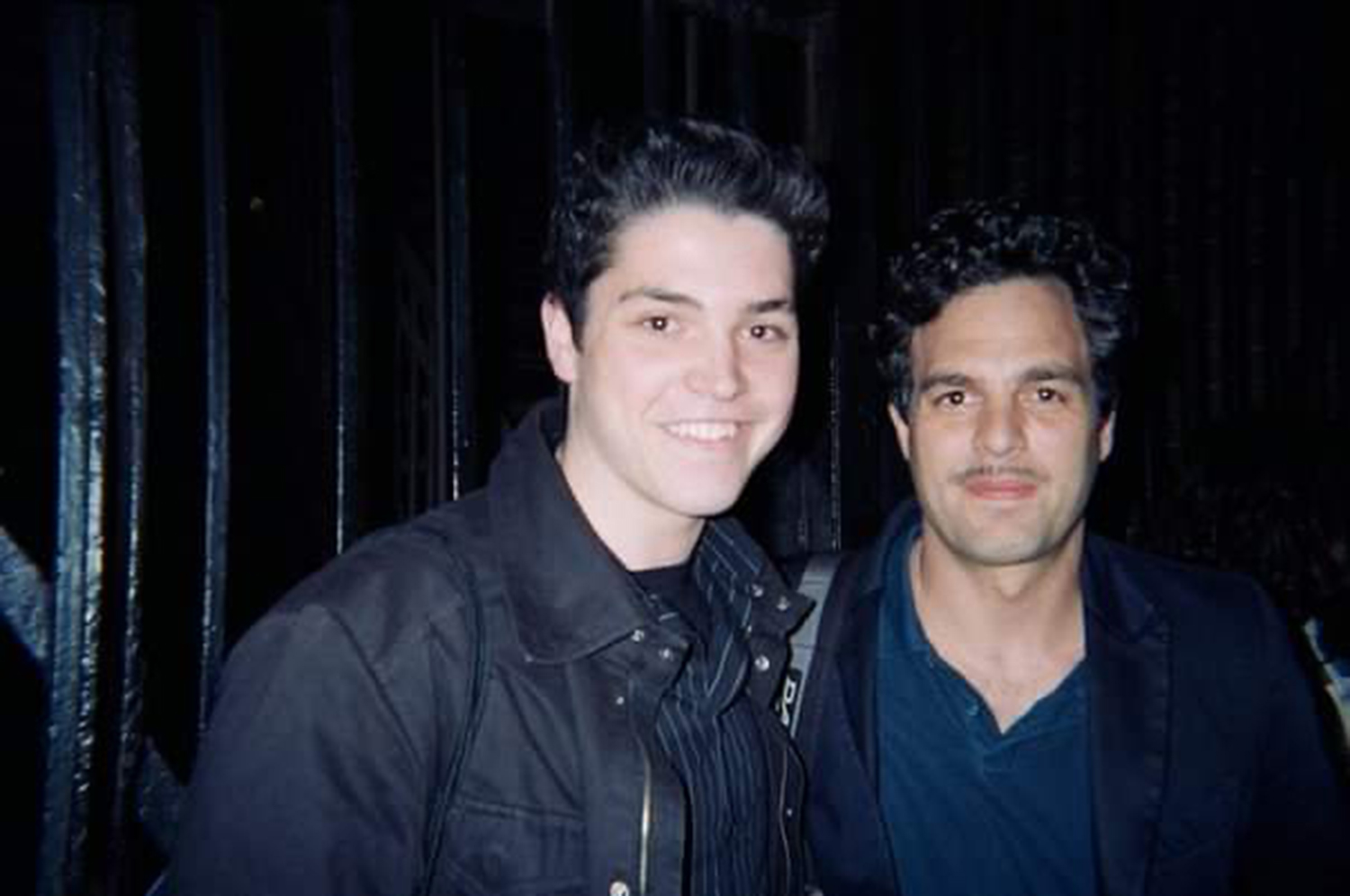

Ettinger and Ruffalo after a performance of Awake and Sing! in 2006.

What do we want from entertainment when the outside world feels so bleak? Are we in search of a balm, or more salt to pour on our wounds? For Mark Ruffalo and Philip Ettinger, the answer leans toward the latter, which makes their new HBO miniseries I Know This Much Is True perfectly tuned to the moment. Ruffalo stars in the writer and director Derek Cianfrance’s six-part adaptation of Wally Lamb’s 1998 novel, playing Dominick and Thomas Birdsey, identical twin brothers who couldn’t be more different. In the show’s first episode, Thomas, a paranoid schizophrenic, severs his own hand in a public library as a sacrifice to god, and the story refuses to let up from there, skipping back and forth in time as it digs into the traumas that have left these brothers so broken. Ettinger, a 34-year-old actor who mined similarly grim territory as a radical environmentalist in 2017’s First Reformed, plays college-age versions of the Birdsey twins, which meant he not only had two play two characters, but also sync his performances to match Ruffalo’s, an actor he grew up idolizing. Here, Ruffalo and Ettinger connected a day after the show’s premiere to discuss why challenging art is better suited to challenging times, and the cathartic experience of bringing this dark story to light. —BEN BARNA

———

PHILIP ETTINGER: How are you doing?

MARK RUFFALO: I’m doing okay, man. I’m feeling really fucking raw today and vulnerable, like I went on a bender and peed on my girlfriend’s parents’ coffee table, thinking that I was having a great time. And then I’m waking up the next morning just saying to myself, “Oh, fuck. What have I done?”

ETTINGER: [Laughs] I re-watched the premiere last night, and it’s much easier to see it a second time. I couldn’t even process it the first time I watched it.

RUFFALO: How did you nail me as Dominick? It’s uncanny to see someone doing a version of me—and doing it so well.

ETTINGER: That means a lot coming from you. I told you this before, but I wrote you a letter when I was doing This Is Our Youth in acting school because you’ve always been an actor that I’ve looked up to [Ruffalo starred in the Kenneth Lonnergan play when it premiered off-Broadway in 1996]. I connected to you more than any actor, the way that you led with vulnerability and an open heart. When this audition came up, to play a younger you, it felt like the universe was handing me something. I watched every interview you’ve ever done, and before every night of shooting, I watched your scenes from You Can Count On Me, because I tried to use that as a template for my version of Dominick.

RUFFALO: I think that Dominick is kind of the 52-year-old version of Terry [Ruffalo’s character in You Can Count On Me], in a weird way.

ETTINGER: That’s so interesting. You’ve gone on to have such an expansive career, and you’re just coming off of the Avengers movies. Does this feel like you’re coming back home in a way?

RUFFALO: Kind of, yeah, because it’s about family, it’s working class, it’s in a small town. It’s real people dealing with real problems in really human ways, and it’s a guy who’s very tough, but there’s something beautiful and sensitive about him. It’s the kind of material I was doing before I did Avengers. It’s probably what I relate to the most. Will it be as popular? Probably not. But as an actor, it’s very meaningful to me. You were shooting Thomas before I did, and you really showed me so much of that character. I don’t know if you could see it, but I was pulling directly from you. And then we had that amazing walk with each other when we met that night, and talked about these two guys and tried to integrate our performances. That was really special. Not many actors would be willing to do that, and I really appreciate you opening yourself up and being vulnerable and the give-and-take that we shared in that 40-block walk.

ETTINGER: I think it happened right before I was about to start shooting, and I was totally shitting-my-pants nervous. Like you said, I was playing Thomas first, and I wanted to make my own choices and follow my instinct. But I’m in support of you, and I wanted to be in service of your performance. That night you opened your heart to me, and it’s a thing I’ll never forget. We were just walking the city streets finding it together. And I didn’t even know this, but one day before I’d play Dominick, I’d do pushups. And then then I found out that you did pushups before—

RUFFALO: Every take.

ETTINGER: The energy was so special on that set. Derek [Cianfrance] sets up a playground where you feel like you’re one organism trying to tell a story. Things would happen that were way past intellectual choices. I’m not a good impressionist, I can’t try to copy you. I just trusted that the energy would work itself out.

RUFFALO: Did you prefer playing one character more than the other?

ETTINGER: With Dominick I would get so angry and frustrated, and then I’d go to my trailer and change into Thomas, and I got to be as present and open and empathetic as possible. So it felt freeing. There’s something about Thomas, he just tells the truth, and sees with a certain type of clarity that’s not fogged up by other things. How about you?

RUFFALO: You had it much more difficult than me because you were doing both characters on the same day. How beautiful and delineated those two performances are is mindblowing. But I had a similar experience. Dominick, like you said, has this armor, he has to project strength, and he uses violence as the final way to resolve an issue, whether it’s emotional or physical. When I started to play Thomas, Derek was like, “Let your stomach go.” And I was like, “What?” And he’s like, “Let your stomach go, man. Stop holding in your stomach!” And I was like, “I’m not holding in my stomach!” And I realized I’ve been holding my stomach in my whole life as a show of masculinity, that I have this strong core, that if someone just came up and punched me in the stomach, I’d be able to take the punch. I’ve spent my whole life on-the-ready in that way. And Thomas is so soft in the stomach. He shows his belly, that softness, that vulnerability. He has a kind of freedom about who he is. I mean, the guy cuts his fucking hand off. We shot that scene on September 11, and when I came in and sat down in the coffee shop, we all took a moment of silence. In the moment of silence, I started praying, spontaneously, just like Thomas started talking, and he was praying for America. And I started to realize that if we had listened to Thomas, we wouldn’t be where we are today. The world would be a different place. The Iraq war would have never happened. We probably wouldn’t have had a second term of Bush. We wouldn’t have had the division in the country that has led to Trump. It’s just so funny that that character who we all write off as crazy, or who we’re afraid of, was so prescient to know what was right.

ETTINGER: What is normal? We’ve created a whole society of structure and time and these jobs we have to do, and that is what makes us important. Yes, there’s a part of Thomas that can flip into extreme paranoia, but I made the decision that it stems from an impulse of ultimate truth. Like you said, he’s right on his impulse. He might take it too far, but there’s a part of him that is way more truthful and way more knowing than almost everyone else around him.

RUFFALO: Did you read the book?

ETTINGER: I read half of the book while I was reading the scripts, and then I put it aside. I’ve saved the other half of the book until this all passes so I can have my own moment with it.

RUFFALO: I totally understand the impulse of wanting to find it on your own. What was working with Derek like?

ETTINGER: When I met with you in the diner, the one thing you said to me was, “Don’t worry, he doesn’t move on until he has what he’s looking for.” I love how Derek is constantly chasing lightning in a bottle, and the ultimate truth. And you think you have it one way, and then he just pushes you into a whole different thing so far beyond anything that I can intellectually think about. It’s the greatest.

RUFFALO: It’s so satisfying and so scary.

ETTINGER: He has such a fine-tuned impulse for watching actors and then pushing them in the right direction. You’ve just got to be game.

RUFFALO: Do you think the material is too heavy for this moment?

ETTINGER: I was wondering how people would take this story during the time that we’re in, but I’ve mostly been watching stuff that has a lot of heart and has a lot of pain and has people struggling to survive. I think everyone has felt pain on many different levels, and I’ve always felt a sense of comfort and a sense of being less alone when I watch truthful stories that deal with real-life shit. I’m at a point in my life where I’m trying to be honest with my own traumas and pain, and it’s interesting how the projects that I’ve done lately have been more of an internal dive into some difficult stuff.

RUFFALO: Everyone wants to be hysterical right now, to just laugh themselves off the fucking cliff, but what I see is a world that’s full of a lot of pain and suffering and loss. And to tell the truth about that in art is a cathartic act, a reminder of who we are as human beings in a moment when I feel like this world we’re living in now is post-human, where the technology is actually leaving mankind behind. The digital image is so packed full of information that our eyes can’t even see all of the information that it’s recording. We can’t keep up with it, and we’re living in our shallow social media selves that are only projected versions of ourselves, but not real or human in any way. So find something that really tells the truth about the human experience, about loss, about love, about connection, about responsibility to each other, about fighting for something—all those things are a good reminder of what it is to be a human being in a time that’s so dehumanizing.

ETTINGER: I feel like such an important part of the struggle of just living is to feel connected to each other, to understand that we aren’t alone.