Jerry Stahl Talks Smack

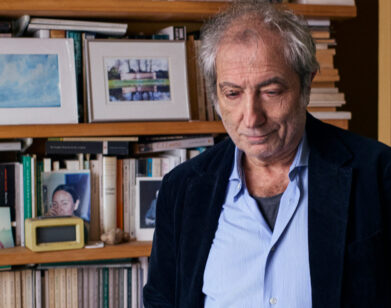

ABOVE: JERRY STAHL. IMAGE COURTESY OF FRANK DELIA

Jerry Stahl is not a junkie scholar. Yet, as editor of The Heroin Chronicles (Akashic), he is an expert. Stahl, who wrote about his junkie past in caustic, honest, and often hilarious tones in his memoir Permanent Midnight, has compiled stories from fellow opiate chasers from Lydia Lunch and Tony O’Neil to Antonia Crane and Nathan Larson. Desperate, degrading, wise, witty, these tales of addiction encompass family struggles, failed relationships, dirty sex, overdoses, and the constant drive for drugs that fuels each vein-digging author. Dispelling myths about the glamour of self-destruction, Stahl has chosen stories that are raw and real, focusing on the often bleak hopelessness of addiction, a life lived day to day with the next high as the only real motivator. And though Stahl is secretive about how many of his contributors are clean, still using, or in recovery, each narrative demonstrates a remarkable self-awareness, a revealing tone that allows readers to relate to addiction, even if they have never picked up a needle themselves. We spoke with Stahl about junkie storytellers, the myth of heroin chic, manipulation, and hand-eye coordination.

ROYAL YOUNG: Junkies have the best stories. Junkies are storytellers.

JERRY STAHL: It comes down to the fact that junkies are liars. They have to be professionally. Back in my journalism days, I interviewed Samuel Jackson and I asked him how he became such a great actor, and he went into this story about how he used to smoke crack or whatever, and he learned how to read people and say either what they needed to hear to give him what he wanted to get, or what they didn’t want to hear that would still get him what he needed to get. That’s the definition of junkie storytelling. Embellish, steal, cajole.

YOUNG: But then they end up weaving a mythology about their own lives.

STAHL: There is that. Junkies will always engage in one-upmanship, like: “I lost a foot shooting into a vein.” “Well, I lost my leg.” You just can’t win.

YOUNG: My dad is a social worker, and he used to work exclusively with junkies, Lower East Side in the early ’90s. There was one woman who would beg on the subway and stuff her shirt so she looked pregnant because she would get more money. One day she was in Central Park taking out the stuffing and someone from the train saw her. Even when she was discovered, there was another level of lie she immediately came up with on the spot.

STAHL: That’s kind of a beautiful story in itself. Did your dad bring all that stuff home to you, these tales of woe?

YOUNG: He took me to work with him.

STAHL: There should be a 12-step group just for guys like you, who got dragged to work by their fathers who worked with junkies.

YOUNG: [laughs] Let’s talk about junkies versus other forms of addiction. What’s the difference, let’s say, with alcoholism?

STAHL: Well, the traditional dictionary definition of the difference is that an alcoholic will steal your wallet in a blackout, come to, and apologize for it. A junkie will steal your wallet and then help you look for it. But ultimately I think all addictions boil down to just not being able to be with yourself for any long degree of time. You need an entire drama to construct your life around to avoid living it.

YOUNG: When does that get dark?

STAHL: That’s a great question. For some people, I guess it never gets dark. You can just live your life that way. But speaking for me, it’s when you realize you’re doing things you don’t even want to do anymore. But you just have this inability to stop doing them.

YOUNG: Do you think being a junkie is more fun than being an alcoholic?

STAHL: Probably depends on the era—[whether] you were a junkie in an era when being a junkie-chic idiot worked for you. It never worked for me because I was never very chic, but I suppose that could be cool. Then back in the Thin Man era, when everyone had their martinis, I suppose that was the optimal time to be an alcoholic.

YOUNG: What happened to those people? Are they all dead?

STAHL: I always figured I myself would never be lucky enough to die, I’d just live on and on in this increasingly dreary spiral. For me there was never a lot of glamor involved in being a junkie, it was about trying to hide the puke and bloodstains on my shirt.

YOUNG: Frankly, I don’t really understand where that glamour comes from, because when you see it up close, it’s really not.

STAHL: Yeah, I think there’s a phenomenon of people who want to be around something that seems “dangerous.” It makes them feel more real.

YOUNG: What do you think is more pathological: to crave being around that or to actually be using?

STAHL: You can’t really compare hells. But I suppose the hell of being strung out on another person’s addictive behavior is its own special thing. I also don’t want to come off as Johnny Junkie Scholar.

YOUNG: What happens when you live your life with this constant need?

STAHL: Essentially all your problems disappear and you only have one problem, which is getting heroin. Your life is pretty black and white because you really can’t do anything until you take care of that. Minor things like mortgage, relationships, jobs, feeding yourself, they all sort of pale before the giant consuming need to get more drugs. When you get clean, ironically, life becomes more difficult. Suddenly you have to deal with all these real-life problems without the luxury of just having one big-ass problem.

YOUNG: Well, that’s part of the escape of it.

STAHL: You’re right. I didn’t realize that when I was in it. I didn’t realize why I was using. Every year that I’m not, I realize why I did.

YOUNG: Could you explain that a little bit more?

STAHL: It’s like the farther you get away from your childhood, the more you realize what was really going on. Whether that is wisdom or time. You’ll just see remnant of that behavior, the reflexive manipulation, the suspicion, that sense of having something you need you’re not getting. It’s a whole way of thinking that even when it no longer applies, it’s become psychic muscle memory. You find yourself thinking like an addict and that can be really horrific. If you’re an asshole, you have an excuse for being an asshole because you’re a junkie. But then once you give up the drugs, and you’re still an asshole, that’s problematic. [laughs]

YOUNG: [laughs] But at the same time, I feel like there are certain parts of being an addict that must serve you even after you stop using.

STAHL: You absolutely learn how to get what you want. You develop very quick hand eye coordination.

THE HEROIN CHRONICLES IS OUT TOMORROW. FOR MORE ON THE BOOK, CLICK HERE.