The time for queer lit is now: a conversation with Alexander Chee

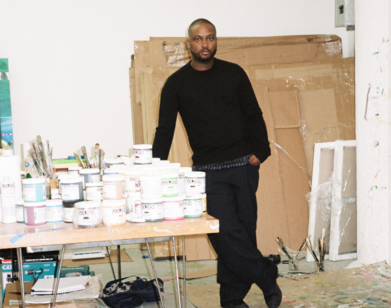

ALEXANDER CHEE AT HIS MANHATTAN APARTMENT, APRIL 2018.

In the third essay of Alexander Chee’s new collection, How to Write an Autobiographical Novel, he details how a well-known college writing professor encouraged her students to locate the spot on the bookstore shelf where their future novels will go. Chee admits to following the advice. “Chabon. Cheever. I put my finger between them and made a space. Soon, I did it every time I went to the bookstore.” If you’ve been paying attention to contemporary American fiction this century, you’ll know that Chee doesn’t need to make the space with his finger anymore. His extraordinary novels, Edinburgh (2001) and The Queen of the Night (2016) now do that work for him.

Novelists tend to be fantasists at heart, and the imaginative powers of fiction don’t always translate seamlessly into sincere and level-eyed essay writing. Thankfully, Chee proves masterful when he turns to descriptions of real life—whether growing up in suburban Maine or protesting on the streets of San Francisco. Rarely does a book of essays come along so affecting, so brave and bluntly honest, and so raw and poetic. I quit underlining my favorite aphoristic lines by the time I reached that third essay: it was useless to try to pick individual diamonds from a whole pile of them.

Chee writes about false starts, family betrays, activism during the height of the AIDS crisis, and his own sexual, political, and racial identity in America. He also writes about growing roses, cater waiting, working as a tarot-card reader, and, most of all, about the difficulties and rewards of being a working writer. Every emerging writer should tap into this collection, for Chee lays it bare: the desire for respect, attention, and money; the search for mentors and historic predecessors; the necessary and unnecessary delusions; and about the importance of giving yourself time. “I think writers are often terrifying to normal people,” Chee muses. “There is almost nothing they will not sell in order to have the time to write. Time is our mink, our Lexus, our mansion.” Chee was first featured in Interview in the May 1993 issue as a young poet. Earlier this month, I met up with Chee in Soho to talk about his collection three decades in the making.

CHRISTOPHER BOLLEN: There’s a very handsome photo of you in Interview from May 1993, along with one of your poems. Do you still write poetry?

ALEXANDER CHEE: Sometimes. It’s funny, there are people who remember me as a poet and have a loyalty to that. And someone asked me on Twitter the other day, “Someday you’ll have a collection of poetry, right?” And I was like, “Will I?” [laughs]

BOLLEN: Well, absolutely no one asks to read the poems I wrote when I was starting out, so it’s telling that people still want poetry from you. When I was reading How To Write an Autobiographical Novel, I kept wavering over whether the book was a memoir or not.

CHEE: I thought of it as an essay collection more than a memoir. I think of it as interconnected stories of the self. The way the collection is structured, you enter different periods of my life. The essays are determined by the subject more than what’s going on with me—although of course I’m very much a part of it. I usually started writing an essay when there’s something I think I know about myself and then I’m introduced to some way in which that original idea is a mistake or there’s new information that shows me a deeper, different layer to it.

BOLLEN: I think this is a collection especially significant for writers because you really chart the arc of that career, starting with working at a bookshop and trying to find your heroes and idols.

CHEE: I think it is also a book for readers. There’s a way in which you start out with me as a reader and a reader who’s turning into a writer and then I become a writer and [then] a teacher. But some of these essays have long lives. I started writing “Girl” in 1994. I went through my files and found it again in 2015 and gave it another revision.

BOLLEN: The essays where you are in San Francisco right after college and taking part in ACT UP protests and going out at night are really so alive and often heartbreaking.

CHEE: Well, I went to college at Wesleyan so I knew about liberal islands. I moved out there in 1989, with some friends. We all wanted to be a part of ACT UP and Queer Nation. We had been going to ACT UP protests in New York and using ACT UP strategies to protest on campus. I was learning the power of the slogan basically. It’s no surprise to me that a lot of people I know from ACT UP went on to be very successful at graphic design, PR, advertising.

BOLLEN: That’s very true. ACT UP had a really wonderful graphic sensibility. Did protests go hand in hand with writing for you in some way?

CHEE: I don’t think I thought of it that way. At the time, it was sort of more like, this is where the most interesting, smart, and honestly attractive people were. It’s hard to underplay the role of that. We were all a little in love with each other. And I also arrived into San Francisco’s queer club scene that was happening. So it was just a very exciting time to be there. And we were doing something in the face of this terrible, terrible epidemic.

BOLLEN: Were you always keeping journals or taking detailed notes in these years?

CHEE: I published my first short story as I left college. And I got an internship at this magazine called OUT/LOOK, a queer journal at the time, and I wrote my first cover story for them as an intern on Queer Nation. The person they had writing the story just never filed, and my editor was like, “So you go to Queer Nation meetings, right?” And I was like, “Yeah.” So I wrote it, and to my great pleasure, it’s cited in a lot of queer history textbooks. At the time, I also fell in love with this man in New York and we started sending each other letters that were 20, 30, 40 pages long sometimes. They were zines of themselves basically, but also even like novellas at times. The picture on the cover of the book is from a group of photos that I took to make those letters for that man. That’s who I’m looking at in the picture or who I imagine I’m looking at in the picture.

BOLLEN: One of my favorite essays in this collection is “Mr. and Mrs. B,” about your time cater waiting parties for the conservative firebrand William F. Buckley Jr and his wife Patricia. It reminded me of all the jobs I took in New York to pay the rent—most of them in the restaurant industry—and how those roles are really wonderful gathering grounds for writing details and whole casts of characters. Cater waiting, especially, allows you inside houses you’d probably never see otherwise.

CHEE: Sometimes you’re a friend of the family, sometimes you’re a tray that talks. It’s that sense of how your role can flip quite suddenly, without any warning depending on who’s talking to you, that you always have to navigate. Some people will feel very warmly towards you, some people won’t quite remember that you’re human. That’s part of what makes it fascinating material. And you’re right, those kinds of jobs do help as a writer.

As I say in that essay, my imagination needed an education in just how strange the world is. You see people in ways that they normally guard from everyone in their lives. So you have a vision of them that is actually a very authorial vision, almost like you would of a character that you had invented. Which is to say, they’re not using any of their usual social pretenses with you because the nature of the relationship is so transactional that it would never occur to them.

BOLLEN: You’re also a great writer about apartments. So many of your essays seem to spring from apartments you’ve lived in or sublet. I have a theory that New Yorkers make for great writers because they move into so many different apartments and buildings and thus you seem so many different lives sharing walls with you. In other cities, you have a free-standing house and you’re done. But in one of your essays, there you are sharing an elevator with Chloë Sevigny. Do you find your apartments to be springboards?

CHEE: I’m laughing about this question because when I came to New York for the first time, I had lunch with an editor friend who wanted to know if I had a novel. One of the things she said at that lunch was so mystifying to me. She said, “I’m so tired of how everything is set in apartments. I’m so tired of all this apartment fiction.” In the very next short story I wrote, all of the characters are outside, riding motorcycles.

BOLLEN: I love apartment fiction! That editor friend is out of her mind.

CHEE: Well, one of my first gigs in New York was in the early life of the digital New York Times. There was a column called “Apartment Envy” in the ’90s and I was one of the regular contributors. Apartments are the conversation that matters in New York, maybe more than what work anyone does.

BOLLEN: In other cities, the subject is cars. But here we can’t ask about cars.

CHEE: You would never ask anyone about a car. But everyone wants to know about your apartment.

BOLLEN: Do you take a different approach to charting an essay than you do a novel or short story?

CHEE: There is a difference. I will write an essay without quite knowing where it’s going to go. But also with an essay, I’m kind of communicating with who I used to be or really searching for that person. There’s different tricks that I come to to help with remembering some of those things. Sometimes I look at my old writing to see what I was trying to do and what can be recuperated. But I also look at my book. My books are ways of remembering my life as well. The book is a memory of a particular time when I bought or read it. I think it’s why it’s so hard for people to combine libraries when they get together with someone. It’s like, your personal library becomes this unconscious portrait of your intellectual history.

BOLLEN: Absolutely. And I currently have a crisis of doubling up now or tripling up on shelves.

CHEE: Just get another apartment!

BOLLEN: I’m trying. Where do you think we are with the current state of gay or queer fiction? Do you think there’s a young audience hungry to read these books? Or do gay kids no longer look for themselves in novels?

CHEE: Oh, they care. They’re very literary. [American artist, writer and gay rights activist] Avram Finkelstein observed that we’re in this beautiful time right now where earlier generations are able to communicate with the older generation—maybe for the first time—and to examine these histories. At the same time, there’s finally an older generation that has survived and is out and can tell their stories to the larger public and that can also reflexively learn from these young people. So it’s this wonderful intergenerational communication that I think is very productive.

I remember Phil Gambone actually asked me something back in 2008 that really stuck with me. He said, “What happened to your generation?” We were going to be this kind of new guard and, you know, I got trapped writing this novel that I wrote for 15 years [laughs], which felt like wandering into a cave and falling under a spell and you can’t escape until the next traveler walks in and so you can leave. [both laugh] I remember when I was writing my first novel and living in New York, there’s a columnist who wrote a book column for The New York Times, and pretty much every season he would write a column about how nobody bought gay fiction and it wasn’t very successful financially.

BOLLEN: It’s such a devastating thing to hear that. I heard that so often as a young writer. Don’t write a gay novel. They don’t sell. No one wants to read them. That message really stops you when you’re young and everyone is repeating that over and over in your ear. They’re basically saying, only write about straight lives, or you’re out of luck.

CHEE: It was like a constant drone of, “Don’t do this. Don’t do this. Don’t do this.” But I think we’re in a period where the publishing industry has been focused for so long on people who don’t buy books, aimed at people who aren’t really readers. Like the people who buy the most books in the United States are black women. But most books are aimed at a white, educated audience that treats reading like a pastime that they hope that they have time for. I’ve often felt that literary culture in the U.S. is not quite paying attention to the excitement about literary culture in the U.S and I think that’s starting to change. For a long time, we were all asked to believe that poetry would never sell and now poets have third-run, fourth-run print runs. Poets like Sam Sacks who’s writing intensely explicit, heartfelt queer poetry. Or Danez Smith. Ocean Vuong is another one, who just sold his new novel at auction. It’s going to do very well.

BOLLEN: Are you working on another novel? Have you entered another cave that you’re waiting for someone else to get you out of?

CHEE: There are about six books that I know I want to write. It got stacked up while I was working on Queen. So yes, I’m already on the new one. The next one is a series of interconnected stories that may or may not become a novel. I’m thinking about something—I don’t know if it has a name actually—that’s kind of a syndrome with gay men of my age who went through the AIDS epidemic and are now in this era where there’s PrEP and people are having bareback sex and it feels surreal, like it’s both a thing that we fought for and nothing we ever imagined and it’s really hard to know what to feel about any of it.

BOLLEN: It’s so hard to rewire the brain after growing up hearing that sex equals death.

CHEE: Yes. And PrEP is like the first sort of victory in some ways that the movement has had related to pleasure in a really long time. It’s also about the cost, who can afford it and who can’t. It creates an economuc class of people who can have bareback sex and who can’t. Which is a really interesting science fiction movie that is also just what we are all just living in right now.

HOW TO WRITE AN AUTOBIOGRAPHICAL NOVEL (MARINER BOOKS) IS AVAILABLE NOW.