ICON

Linda Simpson on Drag Queens, Downtown Scenes, and Underground Zines

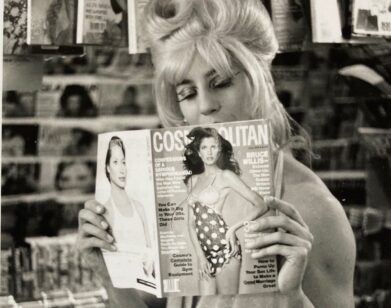

To see Linda Simpson host anything—a bingo game, a drag show, a party— is to witness a masterclass in deadpan camp. This signature dry pizazz jumps off the pages of My Comrade!, too, the mock-Marxist rag she started in 1987. Take the profile of supermodel Connie Fleming, which Simpson begins, “If you never watch TV, go to the movies, or read magazines you might be unfamiliar with The Connie Girl.” Or an illustrated fetishwear trend report about “an exclusive look for gay guys and gals who just love being naughty. No silly sex boundaries for them.” An important record of gay New York and East Village drag, My Comrade! has been getting its flowers over the last few years, having been acquired by Harvard’s Houghton Library, then made the subject of a 35th anniversary exhibition at Howl! Happening Gallery. Now, the zine is featured in a new show at the Brooklyn Museum, Copy Machine Manifestos: Artists Who Make Zines, on view through March 2024.

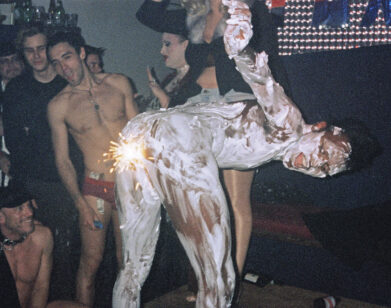

To learn more about the lore, I visited Simpson at her Times Square apartment, where she’s not shy about displaying her own photography on the walls, including a snapshot of RuPaul with vogue legend Willi Ninja. Simpson is frequently described as a drag documentarian because of all the photos she’s taken of her friends and colleagues over the years, gritty, glamorous shots that fill the pages of The Drag Explosion, Simpson’s momentous photo book, something of a monograph-cum-time-capsule published in 2020. Her resumé includes starting the party Slurp, with Telfar and Michael Magnan (the beloved DJ and graphic designer who also art directs the new special issues of My Comrade!). And, in addition to many milestones in the worlds of nightlife and journalism, Simpson wrote, produced, and starred in several plays, in which she could be seen playing everything from a troubled talk-show hostess to a medieval ruler. But it all started with My Comrade!, which Simpson launched after noticing how “tacky and lugubrious” all the gay media was back then. Just before the opening of the Brooklyn Museum show, she and I got together to talk about The Cock’s glory days, reclaiming “tranny,” and a novel she has in the works.

———

WHITNEY MALLETT: I’m curious what you think of the word “zine.” Did you call it a zine when you started?

LINDA SIMPSON: Not really. Not that I was ashamed of calling it a zine, but I called it a magazine because I thought that My Comrade was a couple steps above most zines, in that we were producing original material and doing photo shoots. Not that we weren’t cut and paste with a lot of borrowed materials, but it was maybe a little more advanced than your typical zine.

MALLETT: Yeah, I think zines imply amateur, but in some ways, I think of a zine as having one person’s perspective versus a magazine having multiple.

SIMPSON: Good point. We had people doing art direction and photography and writing for it.

MALLETT: I also wanted to say that the first time I ever was introduced to Linda Simpson, you were the voice of God at a Chez Deep thing at Santos Party House.

SIMPSON: Yes.

MALLETT: Which was a divine way to be introduced to someone. And the next thing I found out about you was that you live in Times Square, and I was like, “God would live in Times Square.”

SIMPSON: Well, thank you very much for putting me on my pedestal.

MALLETT: You started My Comrade in 1987. What were the vibes back then?

SIMPSON: My impetus was basically that it was the peak of the AIDS crisis and I felt very frustrated by mainstream America’s horrible response. But also, gay media back then was pretty tacky. It wasn’t very major. People didn’t work at gay magazines for careers. Tacky and lugubrious.

MALLETT: Oh, lugubrious.

SIMPSON: It was all emphasis on, “We’re dying and the government is not aiding us,” which was true, but there was no pep. The same year that My Comrade started publishing, ACT UP started and there was already somewhat of an activist movement going on. I wanted to take that spirit and put it in this silly, over-the-top revolutionary magazine that was tongue-in-cheek, but still sincere, about gay love and camaraderie.

MALLETT: On the debut issue cover, you have “Tabboo!” with a gun, right? That’s taking the militant activist gear but making it a little campy.

SIMPSON: Yeah. That was when I was just getting into the East Village scene and I was really dazzled by the drag queens over there, so I chose them to be sort of the heroines.

MALLETT: Who were you in 1987? I know you now as a performer, a photographer, and historian, but in 1987, was that a part of your practice already, photographing all your friends in the scene?

SIMPSON: I did, but not as majorly. I had gone to college, dropped out, and eventually got a two-year degree. Then I just was bouncing around the city. I was very directionless. I was always very fascinated by magazines. Do you know George Wayne, the journalist?

MALLETT: Nope.

SIMPSON: He was recently profiled by the New York Times. He has this magazine called R.O.M.E. that was a sort of scrappy Vanity Fair. He just Xeroxed it, put it together, it was cut-and-paste, but it was wittier and more sophisticated than your average zine. I was hanging around George at the time and I was really influenced by his can-do attitude.

MALLETT: Was there a relationship with Pyramid Club?

SIMPSON: Well, at that point, I wasn’t doing drag. I was dipping my toes into the East Village scene, but I was a bystander still. I got to know Tabboo! and Happy Face and Bunny and a little down the road is when my entry into the drag scene happened. I actually started mostly doing drag for these release parties that we would have for the magazine, so that’s sort of when I bit the drag bug, or the drag bug bit me. From there, I went to nightlife.

MALLETT: When Tabboo! was the first cover star, was that a bit of a get at the time?

SIMPSON: I thought so. Tabboo! was part of the East Village scene and certainly one of the stars of the Pyramid. Taboo was showing her artistic skills even back then by doing the Pyramid flyers and posters. Her aesthetic was already pretty imprinted.

MALLETT: She told me that Sade wrote “The Sweetest Taboo” inspired by her.

SIMPSON: Did she seriously tell you that?

MALLETT: Yes. She said Sade was hanging around at Pyramid Club.

SIMPSON: Maybe it’s true. I don’t know.

MALLETT: You were referencing a lot of other magazines. There’s a tabloid one. There’s a Jet and Ebony one. What’s your relationship to these magazines and this homage?

SIMPSON: I was taking elements of magazines that I was really fascinated by when I was young, like Mad Magazine, a satirical magazine, so I think My Comrade had elements of that. Interview was a huge influence on me. Also, there were these rock-and-roll magazines back in the day, like Roxy and Creem, and they covered scenes. They would just go to a party, take photos, put captions, and it was all very insular in a way. My Comrade was like that, too. It was about a certain East Village scene. At the same time, it wasn’t elitist. Everyone was welcome to join in the fun. One of my goals was to include people that weren’t getting any coverage anywhere else.

MALLETT: That’s also why I was inspired to do The Whitney Review, too.

SIMPSON: I think it was the fourth issue when I decided to do Sister, which was the compatriot magazine of My Comrade, and that was the flip side.

MALLETT: You have My Comrade, and then you flip it over and it’s Sister?

SIMPSON: Yeah. For this particular “best of” issue, we just incorporated Sister stuff into the magazine. That was great, because I didn’t want My Comrade to be completely male-centric. Throughout the ages, the gay male movement has had a tendency to overshadow, especially during the AIDS crisis, so it was really important for women to get their due. It wasn’t always easy getting content, because I didn’t know as many gay women, and there weren’t as many in our particular scene.

MALLETT: Okay. In addition to the Brooklyn Museum show, a couple of years ago—it’s an important historical record—you’re in the Harvard Houghton Library. And in the past two years, there’s been more energy in archiving or historicizing what you were doing. Then you had the show at Howell. I really enjoyed all the panels, like the Straight To Hell.

SIMPSON: Oh, those were fun, weren’t they?

MALLETT: Yeah. How do you feel My Comrade fits into the Copy Machine show?

SIMPSON: I was only at the preview party, but I was happy that the show did include quite a bit of queer content. I think My Comrade certainly was one of the more prominent magazines in that ‘80s, ‘90s era, so I was really happy to see that it got its due. Not to bad talk anyone, but I’ve been in a couple of other zine shows where we’ve got 1,000 zines on display and you walk in and the walls are just covered with pages and covers of magazines. It’s just overwhelming and everything becomes very flattened. I like to think of My Comrade as being significant. So I’m glad to see it get its due in the spotlight in that exhibit.

MALLETT: Your 35th anniversary issue featured people like Macy Rodman and Christeene. Do you feel like you’ve created a lineage since then? They’re weirdos.

SIMPSON: Edgy.

MALLETT: Raw.

SIMPSON: That’s accurate. I think there’s a certain sensibility among some people, especially queer people, that continues through the ages. I didn’t want My Comrade’s last issue to be like, “Here’s this old zine,” just with oldsters in there. I wanted it to be fresh, and putting people in there that are a bit younger just revs up the magazine. It’s good for everybody.

MALLETT: The last time we talked at length, you also mentioned adapting one of your plays to a novel. Do you want to tease it at all?

SIMPSON: Why not? I’ve been secretive and closed about it, so maybe talking about it might help get it produced. I wrote a play back in ’97 or ‘98 and it was produced at PS 122, which is now known as PS on First Avenue. It’s called, get this, The Tranny Chase. This was before the language wars, and the story is basically the trials and travails of drag queens with romance and sex. It’s been really tough, because most of my writing was nonfiction, and all of a sudden I had to change gears and start writing fiction. But I really am enjoying the process. Of course, the title is controversial in this day and age, and if I want to keep the title, I probably have to completely print it on my own and treat it as an underground book. I can be flexible and shop it around with a different title, but I can’t change some of the language in the book. It’s real. I’m not trying to be exploitative or rile anyone up. I’m using “tranny” as a term that was frequently used by practically anyone that did drag or was transgender back then, just in a descriptive way. When that word became demonized several years ago, I would read Ackman saying, “The last thing a transgender person hears is someone yelling, ‘tranny’ as they get beaten to death.” That’s not true, at least in my gay-bashing or drag-bashing experiences. Some would yell “fag,” or “that’s a dude.” Tranny? It’s almost such a faggy word that straight people are not going to use it.

MALLETT: I see what you mean. Michael Magnan is also part of your newer issues. How long does your collaboration go back?

SIMPSON: Michael’s art directed the last two issues, but I had worked with Michael on other graphic stuff, especially when we did parties together. He would make the invites and I would sometimes suggest ideas or provide the text. Michael is really, really good at art designing.

MALLETT: Did you guys do a party at The Cock?

SIMPSON: Yeah. We did a party called “Slurp.” They were DJs, and Michael did a lot of the graphics, and then I was the host and organized the entertainment. The Cock is actually celebrating a 25th anniversary, so we’re all going to be at the party recreating a reunion of Slurp.

MALLETT: At the Howell show, when the pages were on the wall, I did love the ads, because that’s really a time capsule.

SIMPSON: Yeah. It really was. There were more mom-and-pop stores. It was another era when people went out to buy magazines. They went out to buy clothing.

MALLETT: Would you just approach small businesses?

SIMPSON: Yup. Sometimes I was approached but most of the time, it was me beating the pavement. Maybe I wasn’t great at delegating but, also, there just wasn’t any money to give anybody, you know? What’s your plan for The Whitney Review? To survive on advertising?

MALLETT: That’s my plan right now. I am looking into grants, but for a lot of the grants, you need to exist for two years or four issues. It’s funny, because isn’t that the time you need the money the most, in the beginning? I guess you need to prove your legitimacy. People still will pay to be in a magazine, more money than they’ll pay to be on a website, so there is still a print model that way.

SIMPSON: I really enjoyed the first issue of the review that I got. Michael [Bullock] interviewed Brontez [Purnell]. I’ve read—what is it, 100 boyfriends? 1,000 boyfriends?

MALLETT: 100 Boyfriends.

SIMPSON: 10,000 boyfriends!

MALLETT: A million boyfriends!

SIMPSON: He’s great for interviews. I enjoy books that I can read over and over and over. I read The Diaries of Sean DeLear, which was very entertaining.

MALLETT: So joyful.

SIMPSON: It was. It was bumpy, some of his life, but he always seemed to have this optimistic attitude and I love how it reminded me of when you’re a teenager and he’s like, “I love Peter, I love Peter, and, P.S., I love Peter,” and you never hear about Peter again. [Laughs]

MALLETT: You come on hot and strong for somebody and then, a week later, at the bowling alley, you’re like, “Ew.” It really captures a teen spirit.

SIMPSON: [Laughs] It really does. “It was bitchin’.” I met Sean DeLear a couple times as a young adult, but didn’t know him well. It made me wish I had known him better.

MALLETT: Yeah.

SIMPSON: Can you tell me what time it is? The reason I’m in drag is because I’m doing a virtual Bingo. That’s why I have this gold curtain up. It’s kind of my set. I do it right here in the corner.

MALLETT: It’s 3:06. We can stop now.