blonde ambition

The Artist Martine Gutierrez Goes Blonde

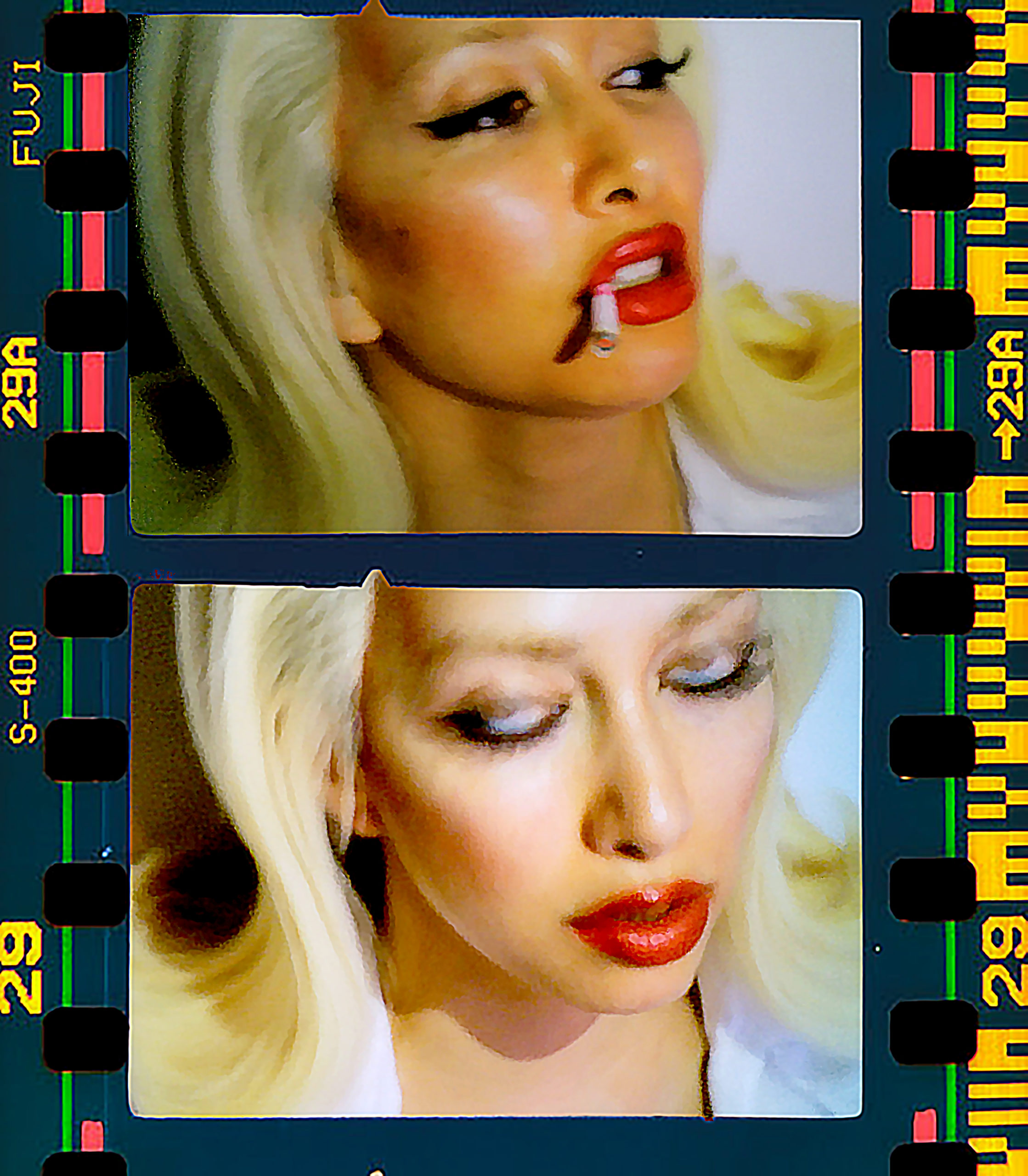

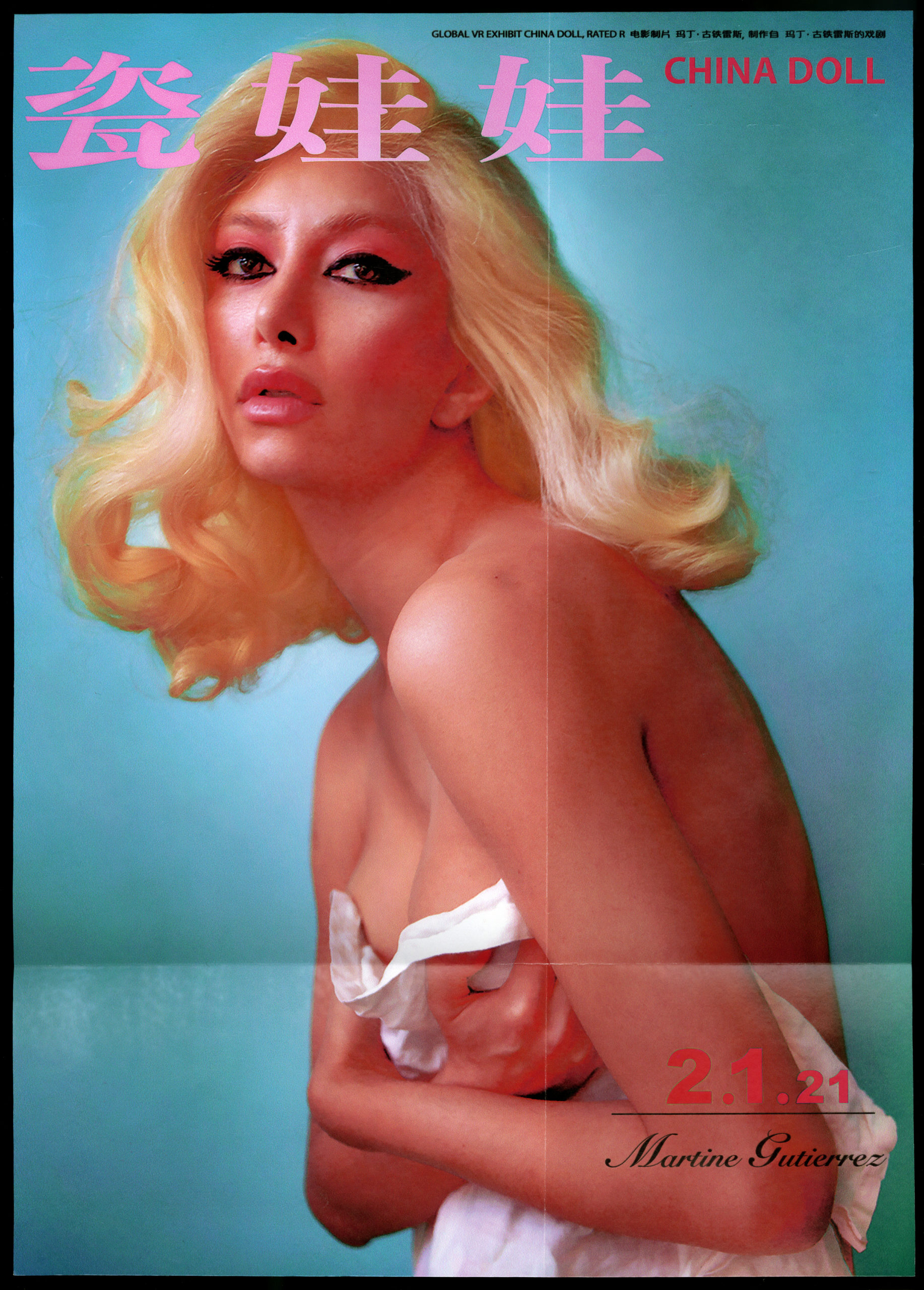

When Martine Gutierrez, the artist known for Indigenous Woman, a book produced by and starring herself, reached out asking to speak about her new film China Doll, I wanted to understand, “Why me?” In the film—the main feature of her latest show, CHINA DOLL, Rated R., a VR exhibition at Ryan Lee Gallery—Gutierrez once again plays the titular role. She is a blonde bombshell, the epitome of femininity and the product of Hollywood’s highest ideals. A persona built to entice and intoxicate the audience, it’s fantasy personified. So, why me? Having been through Idol camp in Asia, where Idols are manufactured through rigorous dance classes, singing lessons, and strategically styled outfits and hairdos, I am all too familiar with the transformative tools of flawless makeup and the perfect curls. Gutierrez and I are constructed from the same fantasy, just translated differently. So from this Idol to her Bombshell, speaking from two ends of the world, we discuss fame, celebrity, and the scandalous beauty of being blonde in the industry.

———

BLAKE ABBIE: You look radiant after last night’s opening.

MARTINE GUTIERREZ: This digital exhibition feels like the closest thing to an opening I could create. Usually, it feels like a wedding, where I’m the bride and groom. I miss it very much. Anyway, I’ve stopped sleeping and went to bed at seven in the morning. Nothing else matters right now. What else do I have to do?

ABBIE: Time doesn’t exist.

GUTIERREZ: I hate it. I’ve seen everything on Netflix. There’s nothing left to see, Blake.

ABBIE: I consumed so much content last week.

GUTIERREZ: Everyone is this ripe sponge now. Do people want to listen to others say, “Wow, this is so weird, sad, and hard?” Or, do they want escapism? They want to believe in something. They want mythology.

ABBIE: So, you’re Aphrodite. That’s sexy. Aligned with the Bombshell.

GUTIERREZ: With who I am right now, perhaps.

ABBIE: The star.

GUTIERREZ: I don’t know how this works. I’ll have to ask my manager.

ABBIE: My team just does it all for me. We’re at a place where we don’t have to think.

GUTIERREZ: That’s luxury. Luxury is the place where everything is done. It’s relief, really.

ABBIE: So you’re alone?

GUTIERREZ: I’ve been alone for several months. It’s been fab.

ABBIE: You were filming and you’ve been alone this time. What’s your sense of making something now? You’ve always worked alone.

GUTIERREZ: I have. I thrive in it. I was compartmentalizing to be like, “This is COVID and you’re allowed to be this way, disappear and focus on asking ‘Why?’” I love that question applied to anything. That’s what made me an annoying child. We’d watch a movie and I’d be like, “Why did they do that?” It didn’t make sense to me. If you really shed the hype, which is what this year forced everyone to do, you look at a character like Road Runner: Who is he, standing still? The character doesn’t work. You have to rewrite and recast him.

ABBIE: Let’s talk about the characters in your film.

GUTIERREZ: Well, I was locked in a pool with a few toys and had to entertain myself. There are three “actors.” Two men and a woman; she’s playing me. Or I’m playing her. That’s unclear. It’s funny when you don’t have real actors, and you’re the writer and the director, and you don’t have to check in with your co-stars about what you’re asking them to do.

ABBIE: Boundaries can be crossed.

GUTIERREZ: This experience was no doubt inappropriate because the intention was unclear, which is exciting because I’m not an actress. I just play one in the movies.

ABBIE: She says, throwing her hair over her shoulder with a little wink.

GUTIERRES: As she takes a sip of her Pellegrino.

ABBIE: I have oolong tea, handpicked, hand-rolled. It’s in my rider. So, she’s an actor, dancer, artiste, model, singer, songwriter…

GUTIERREZ: Everything a true Caucasian needs to be. I am bred for greatness. I know how to set a table, but would never. I know how to use cutlery correctly, all those forks and spoons.

ABBIE: The tiny ones.

GUTIERREZ: The Barbie spoon. With the film, I want to believe in love and things that last forever, I just haven’t experienced that. Trying to get my parents back together, very Parent Trap. Believing that maybe when I’m with my father, there’s another me with my mother, and they think I don’t know and can keep lying.

ABBIE: You’re a true Lindsay Lohan.

GUTIERREZ: I’m the dark side of Lindsay, the underground fame. No one can dictate how we’re famous and what for. It’s less of a question of when, and obviously why. My favorite question, “Why are they famous?” At this moment, we all can be and are. We all are porn stars. OnlyFans has changed that. It’s giving the platform of autonomy to everyone. Just how Hollywood doesn’t work when Netflix can make Academy Award-winning movies.

ABBIE: Or doesn’t work now that we can make our own movies.

GUTIERREZ: Exactly.

ABBIE: The glamour is gone.

GUTIERREZ: Glamour only works from a distance, from the outside looking in. It’s like, “Well, now you can just do it.” When everyone is Paris Hilton, no one is scandalous.

ABBIE: The tabloid scandal that came out before your film’s release is shockingly hot.

GUTIERREZ: Is it? Thank you. I’m like, “What is infamous nowadays? Should that matter?” Being in the swimming pool felt symbolically correct, like a portrait of solitary confinement. A beautiful echoing prison. A chamber of light reflecting—probably terrible for my skin.

ABBIE: How about more SPF?

GUTIERREZ: I sweat it off! I do all my own stunts, even the lovemaking.

ABBIE: I was actually wondering about the sex scenes. They’re un-simulated. Did you build intimacy between you and your costars, Rocco and Diego Carlos?

GUTIERREZ: We’re actors. There has to be trust. It was easy because they’re both attractive. But we’re all playing a part. It’s not real.

ABBIE: Was it your first time having sex on camera? Maybe that’s inappropriate to ask.

GUTIERREZ: No, it’s not. It’s funny because I think of Chloë Sevigny. “It was a subversive act. It was a risk,” she told Variety about The Brown Bunny. I get confused sometimes objectifying myself. “Only I’m allowed to do it.” It’s very: “I say who, I say when.” Vivian Ward, from Pretty Woman, she’s our favorite prostitute. I find that poetic.

ABBIE: Do you use the mirrors in the film as a way to reflect on yourself?

GUTIERREZ: The mirror is interesting because it’s truth, but not. It’s a thoughtful place. It feels like an altar that asks you to check in with where you are right now. It sees everything.

ABBIE: And you are able to see everything, too.

GUTIERREZ: You can look at it, and hold yourself a certain way. But you know you’re playing at it if it’s not something you can comfortably face. And we need this counterpart. There’s no real in-between. There is dark and light. The two need to co-exist. You can’t just banish one, that’s banishing both. That speaks to where we’re at politically. If you make or invent a new thing, it will create itself because it exists. It’s like relativity. It’s very Marxist.

ABBIE: Understanding the light and dark, your manipulation of shadows in the film, is also interesting. You can’t see a hand—you see the shadow and know what’s there. I want to ask about the peach and the millipede. Why did you want to include that? We know what the peach means, we know what a millipede could represent.

GUTIERREZ: In my mind, when editing suggestively like you’re describing, the shadow conceals who bit into the peach, so the action can become a symbol. Whether the symbol is knowledge, or corruption or innocence lost, it is vibrance in a new wound, a sparkling drip. To watch something be ruined is so beautiful. In the pool, millipedes wouldn’t leave me alone. We would shoot a scene if they would let me pick them up, and I’d be like, “Okay, thank you.” It feels biblical in a sci-fi way for an insect to give snake.

ABBIE: And the peach gives apple.

GUTIERREZ: It was also summer. Peaches were ripe, a temptation even when not filming. Placing one in front of the camera became a character, undeniably. We live in an era where everything is a reference. Right? We can’t refuse a reference now. And you can just co-exist with not knowing the reference—until someone educates you. That’s the other place we’re at, where everyone is educating each other, constantly. That’s like what being is. Or something.

ABBIE: Post-art school, everyone wants to be enlightened. And also, everyone feels entitled to enlighten.

GUTIERREZ: Ew. Not perpetually in art school. I’m going to get water.

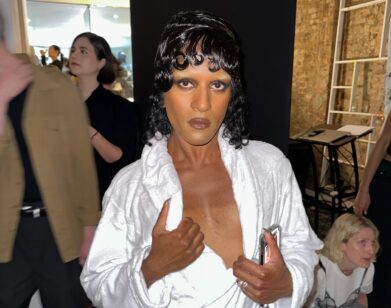

ABBIE: They should have just brought it to you. I want to ask about your evolution. You’ve said to me you’re at the peak of femininity, that you don’t get clocked. I think you meant you have less of a range of gender play and are more in your womanhood.

GUTIERREZ: The drag of my body has cast me as a woman. As someone who was writing about gender and has been critical in speaking about perception, it’s astonishing to walk into privilege with the doors held open. The strongest parallel is in becoming blonde.

ABBIE: You look at our counterparts in the industry, and as soon as someone goes blonde, there’s a shift. Or maybe it’s even more noticeable when a blonde chooses to become not blonde.

GUTIERREZ: Scarlett Johansson becomes a brunette and you’re like, “Oh no, who is this? What happened?”

ABBIE: There’s almost this ownership of other people’s blondness.

GUTIERREZ: Absolutely. It feels insulting.

ABBIE: Blondness being a construct, or even a tool people use to underscore this idea of femininity. Or even the word “blonde” having both a masculine and feminine spelling.

GUTIERREZ: Blondness doesn’t ever really exist, with or without the ‘e.’ She’s still this thing that Marilyn puts on, Madonna puts on, Scarlett puts on. Different generations and demographics understand her as reality because they aspire to this thing. But she herself aspires to it too. It’s so fixed by media, but it’s so unfixed as a place to stay for anyone. It’s beautiful, beautifully strange.

ABBIE: Why don’t you go blonde?

GUTIERREZ: Because I like tactility. Sound and touch are the most sensual things. Sound, I can control. Touch, I can control by keeping things around me that are pleasant. I’m still imagining the mass of all this [hair] becoming a new material that will act differently. I’ll have to cut it off, which is fine, but it will still feel disgusting. Like a scrubby sponge around my head. Though now, with science, who knows?

ABBIE: Maybe you want the choice to take off the blonde and that persona.

GUTIERREZ: I love taking off my wig and looking at it as a symbol. I’m literally still the girl in my movie. I guess I cast her for a reason. It’s so weird making something that feels like an extension of reality, of who I am—but it isn’t.

ABBIE: Maybe, as you said, it’s the opposite of the reflection of your reality. Do you see this role in relation to those you undertook in creating previous works in the past, like Indigenous Woman?

GUTIERREZ: Yes, it’s the mirror. It’s the same frame of mind. This is Indigenous Woman’s counterpart, a reaction still asking, “Is this real?” As an American, I was raised on Americana iconography, which China Doll embodies. She is the white woman other white women aspired to be. Her position points irrefutably back at herself. So, how do I tear her down? I have to kiss her.

ABBIE: And you do in the film. I want to understand your relationship with the Chinese language and cinema, which you use in your film.

GUTIERREZ: Text over moving image is so ugly but so nostalgic. I grew up on my dad’s bootlegs. He watches everything with subtitles because audibly English is harder for him to understand, and riddled with homonyms. Dad says he learned English by reading the funnies and watching martial arts movies. He loved Jackie Chan because people said they looked alike. Growing up we saw Jackie Chan commercialize into Rush Hour. He was my J-Lo. I was like, “He did it.”

ABBIE: This film has a poem.

GUTIERREZ: The poem in Chinese characters over music, and then spoken with subtitles. To me, it’s very Star Wars.

ABBIE: It’s also ’90s new wave Chinese films; you probably recognize this. They have a text that establishes the scene, setting and background, which is what this poem does.

GUTIERREZ: Yes. There’s so little going on. Everything is so still. It’s not linear, yet feels like a loop. Which is what time kind of feels like. We keep doing laundry, somehow there’s always more laundry. A woman’s work.

ABBIE: Is it the reason you chose all white?

GUTIERREZ: It looks stunning when clean. But there’s something about how it just never stays clean. That’s why you wash. You’re just getting it ready to be destroyed, again.

ABBIE: The essence of womanhood. Are you going to have a Blonde Ambition World Tour?

GUTIERREZ: I made so much music at one point, and then didn’t release any of it. That’s what happens when you are the producer of your own pop star. The issue is control, and learning to relinquish it.

ABBIE: What’s the difference between that and having work in a gallery?

GUTIERREZ: Because that’s when I’ve said, “I’m done touching. I’m done fondling it.” There’s something I enjoy about the space of clay. Nothing is hard yet. It’s begging me to make up its mind: “Have an opinion.” What a moment to be decisive.

ABBIE: It seems the natural evolution of an entertainer. Once you’ve captured our hearts in one way, you move to another way to entertain. I’m into this idea that you are a singer, songwriter, actor, director, producer.

GUTIERREZ: I’d love a choreo moment.

ABBIE: Have you tried TikTok?

GUTIERREZ: I’m afraid I’ll like it too much, and I’ll never come back.

ABBIE: Why does that scare you?

GUTIERREZ: Because it’s not real. I’d rather interrogate something I’ve cultivated, like, “Come here, and then we’ll talk about it.” Blonde is also that. Blonde is the avatar.

ABBIE: It could be an extension of that world. Imagine the next thing you do is a collaboration with BTS, the boy band.

GUTIERREZ: I would die. That would really be fierce.