Into: The Nihilistic Doodles of “Avocado Ibuprofen”

“Into” is a series dedicated to objects, artworks, garments, exhibitions, and all orders of things that we are into — and there really isn’t a lot more to it than that. Today: Shanti Escalante makes a case for the cathartic nihilism of the cartoonist Jaako Pallasvuo, also known as “Avocado Ibuprofen.”

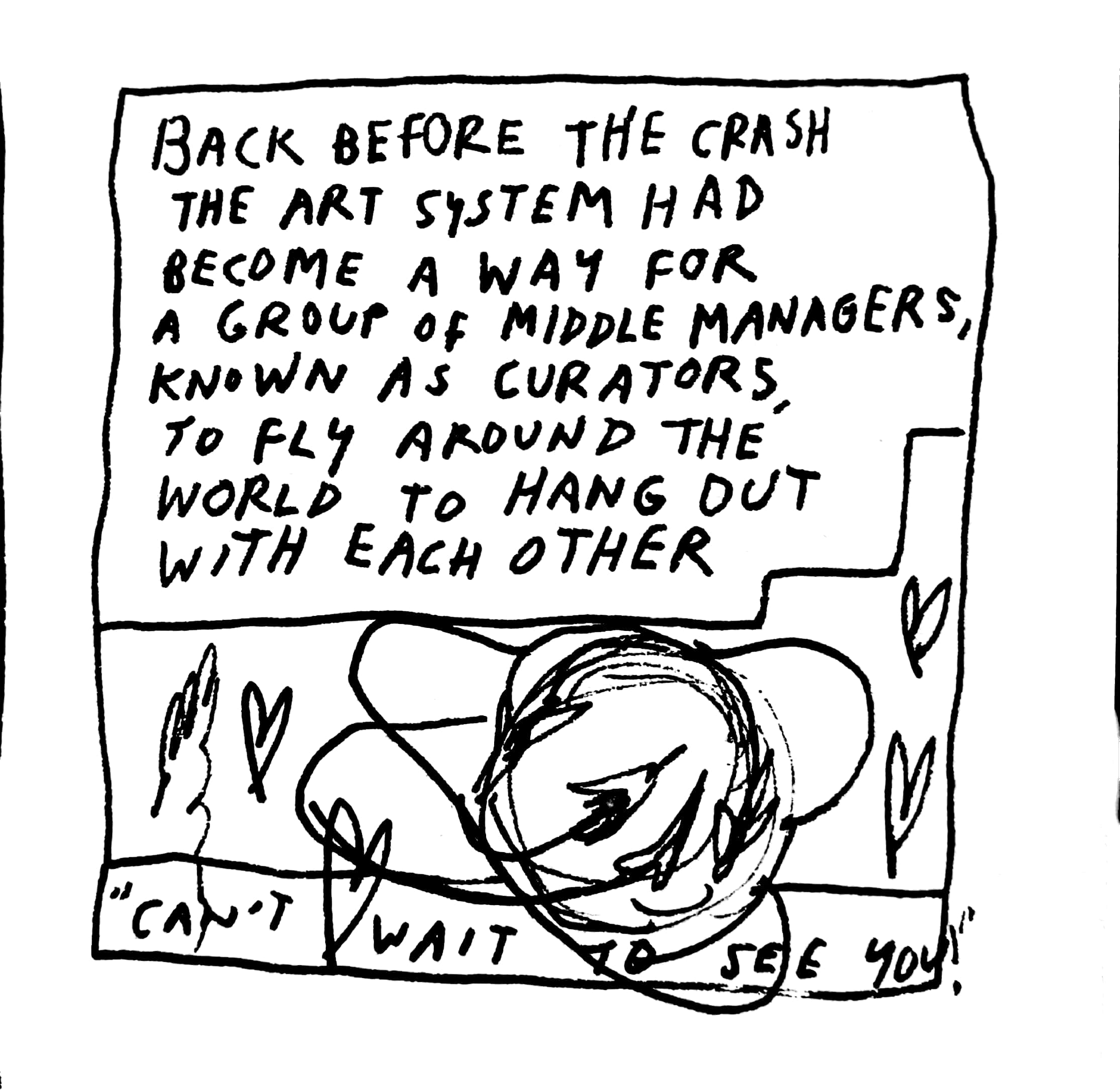

Vulnerable, funny, and often surprisingly touching, @avocado_ibuprofen is a digital comic book that chronicles Jaako Pallasvuo’s on-the-fly rants about the art world, the anxiety of performance in the social media age, and the guilt and disempowerment that comes with living on a dying planet. His comics, mostly drawn in pen or black marker, possess the dreamy yet convincing logic that comes from creating in a digital stream of consciousness; each swipe reveals a new panel, bringing us to a place we never expected to go. Pallasvuo’s meandering route threads itself through thousands of comics, always asking: Can we fake a self that will perform well on and offline? And even if we can, should we?

As Jia Tolentino points out in her book Trick Mirror: Reflections on Self-Delusion, having a likable online persona can be the difference between paying off your medical bills through a viral GoFundMe or floundering in debt. But not all of us can isolate, track, and invest in a cult following, whether on social media or in real life. In one of Pallasvuo’s comics, he writes “sketches for ‘universally’ relatable generic cartoons for courting a broader following (500k goal)” followed by images of pizza, a coffee drinking dog-centaur, and metaphorical sketches masquerading as deep meditations on life—like a stick figure climbing stairs labeled “my problems.” His best work brings in Garfield, who is at once a symbol of disappointing laziness and hollow commercial success. To read a comic that is at once lighthearted and vulnerable about the anxieties of performing well in the social media age is extremely cathartic. We savor each moment of insecurity and doubt Pallasvuo projects, finding ourselves in his loose-lined stick figures. If we are failing, negative, unsure, and above all, unseen—then at least we’re real.

But to understand Pallasvuo’s comics as just another neurotic, meme-like product to soothe millennial anxieties would be reductive. The anxieties he has are all centered on living in an unethical economic system that fuels all kinds of abuses, and Pallasvuo worries that investing too much into curating a successful persona, online and off, only distracts from the larger problems our world is facing. In another comic, he writes, “To be bad was to be alienated, unempathetic, cruel. A tool of the system/To be good was to be full of unplaceable anxiety and remorse at all times.” The comic ends on a sparse desert scene that feels biblical; the moon hangs in the air and a small group of people are surrounded on all sides by nothingness, with the caption reading “Grace was absent. Mercy didn’t belong here.” Pallasvuo depicts, with simplicity and crossed out lines, the horrible state of compromise we’re all living in. Though at times nihilistic, his comics tap into something essential: maybe by being messy, incomplete, and unsuccessful, we’re actually engaging in a sort of passive resistance against capitalism. And if that doesn’t make you feel better about your follow count, what will?