OPENING

In His New Show, Painter Greg Ito Goes Swimming With Sharks

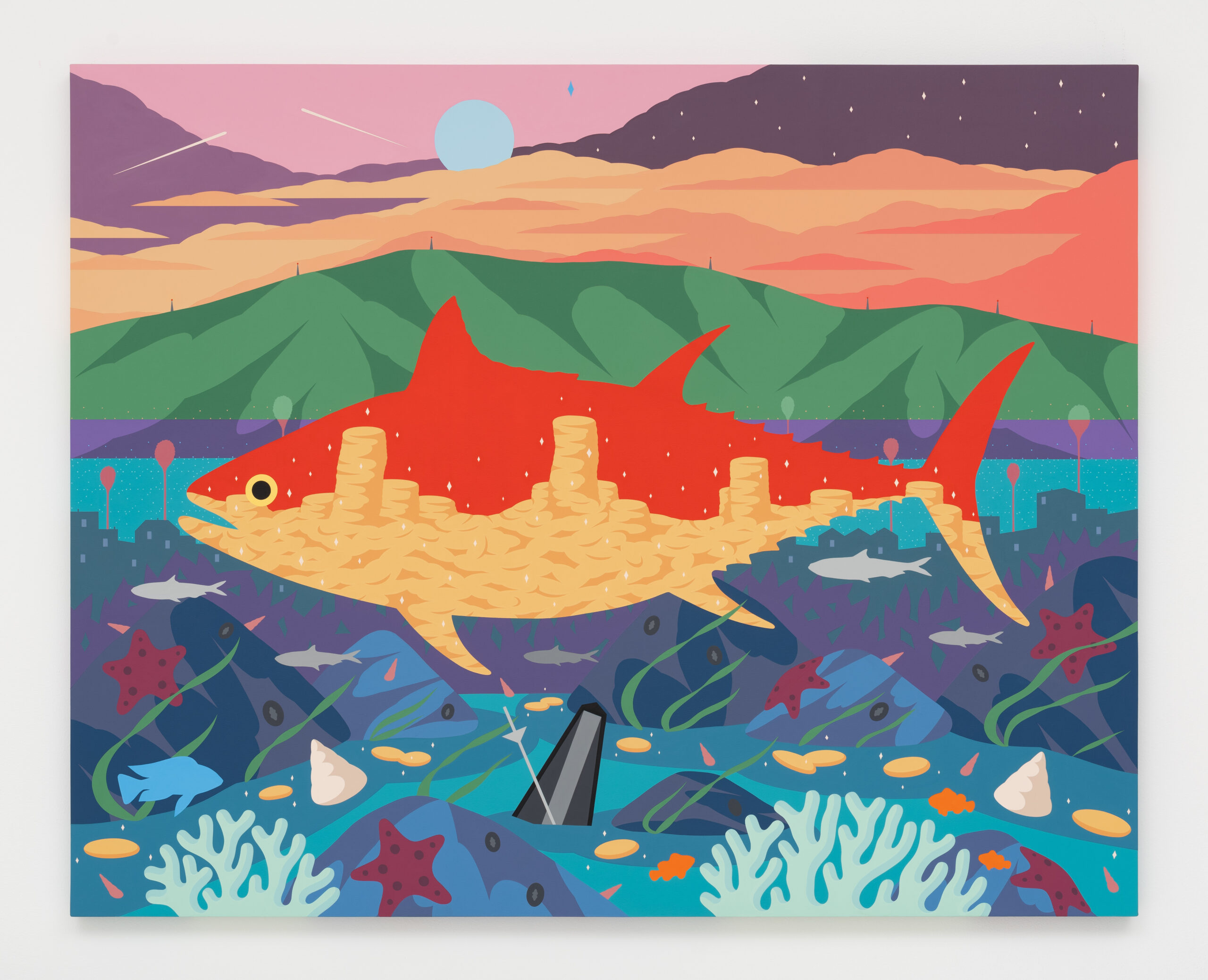

There’s a gold shark erupting from the concrete floor of Anat Ebgi gallery. The provocateur? Greg Ito, the Los Angeles-based painter who’s meticulously crafted mattress-sized frames he renders using Home Depot paint. His show, Sink or Swim, features pastel paintings that at first look like soft, aquatic menageries, but whose details suggest heavier preoccupations: a monopoly-sized house bobbing on surf, empty beer bottles scattered on an ocean floor, a fish stuffed with coins, sinking. “That’s how I’ve been feeling for the last year,” Ito says about the title. “I feel like I’ve been treading water.” But despite the real and symbolic “flood,” the scenes have flares of hope: “It’s the forcing through a difficult time of the waterline, that transition of letting go of an addiction to breed a better life,” Ito explained to fellow painter Derrick Adams, who has two shows of his own on view now: Blues People at Newark Express and Sanctuary at Middlebury College Museum of Art. Ahead of Ito’s opening, Adams got on Zoom to talk to him about trading the “shiny artists persona” for a more authentic, and unsteady, artistic life.—ELOISE KING-CLEMENTS

———

DERRICK ADAMS: Hey, Greg. What’s going on?

GREG ITO: I’m good, thank you. How are you?

ADAMS: I’m doing great. Just taking a little studio break. I had the pleasure of seeing one of your works in person at the gallery a couple of months ago when they installed a group exhibition. Prior to seeing the work in person, I was impressed with the visibility of it from a digital aspect, seeing the color and the composition. That was one of the things that really stood out. Your use of color and your very distinct color palette seemed really interesting. Seeing it in person, you get to see a little bit more of the hand, the way that you handle the hard edge line and color blocking, I saw it as a really interesting refinement. I’d love to hear a little bit more about it.

ITO: Totally. Thanks so much for accepting the invitation to do this. I’ve also been following your work for some time, and I really enjoyed themes in your work, particularly the focus on Black joy. For me, I feel like when I’m working on my paintings, it’s almost as if I’m cleaning a dirty mirror, like I’m trying to look at myself and understand something in my life. I’m a father now. My daughter’s three years old. The past three years have been such a roller coaster, and I feel like my work helped me navigate through a lot of the more difficult times. As I’m painting and composing my images, it’s like I get a little bit closer to seeing a piece of myself that I just didn’t really understand. My wife is Black, so we’re a mixed-race household. She’s learning things about me and my culture, and I’m learning about hers every day. When I first started my artistic journey, a lot of it had to do with my Japanese-American heritage and honoring the family lore that came out of the internment camps and how these polished family stories really carry my parents and myself through our hardships. It’s similar to how Black history is also so dark, but people were still building families during those times and persevering. The current show is called Sink or Swim and that’s how I’ve been feeling for the last year. When I first started painting and working with Anat [Ebgi, the gallery] in February 2020, I did Frieze L.A. and it did really well. But in the last year, I feel like I’ve been facing so many personal challenges. I felt such a weight on my shoulders. When my baby was first born, I’m like, “Yo, I’m going to get everything organized, work on my art, build our family structure, our safe haven.” Three years down the road, I don’t know if I’m any closer to my goal. I feel like I’ve been treading water. I look back at my family’s past for inspiration, but lately I can’t really turn to that as much as I did before. I have to hyper focus on what’s happening now. And lately, I find that everybody’s in the same boat.

ADAMS: Yeah, totally. The idea of happiness or success, you have to also realize, especially as creatives, that it’s more so a feeling that’s reflected from within. I don’t believe in setting goals for yourself that are based on just aspirations. I believe in goals as being things that you can physically do.

ITO: Same.

ADAMS: Things that you can execute, that you can strategize, put a plan out and make happen for yourself. So the title of your exhibition resonates with me in many different ways because I think that if anything, it’s something that’s very common in the creative community now more than ever, especially with artists of your generation. It’s really more about focus, but also being able to have tunnel vision because there’s so many different things that are coming through media output that constantly feed feelings of inadequacy, feelings of feeling…

ITO: Fear.

ADAMS: Fear, feeling like you’re not where you’re supposed to be. The shark piece, especially. What first drew me into your work is the way that you are able to combine these very opposing colors together to make a more synthesized experience through color and very flat tones. If you’re lucky as an artist, the idea of fear and failure should never stop. You should always feel that you’re not fully realized as a person, as an artist. What’s really exciting about making art is not knowing what’s at the end of the tunnel, looking at fear or failure as a necessary evil. And for me, I never think about my work in a museum context or a gallery context. I usually think that once it leaves my studio, it has another life that’s beyond the life that I had in my studio. It’s really more about the discovery of adding color and seeing how things work next to each other and that tension and that psychological experience for me as an artist to see things that are floating around my brain virtually now existing in the real world.

ITO: You touched on a few notes that really struck me because I’ve known your work. It lives in different kinds of spaces. It’s not just a museum gallery, but it’s also a public space. And for me, with my work, I want it to be extremely accessible. It’s really amazing to me when I have an elderly person access my work, and then I see my daughter look at stuff and she’s like, “That’s a clock.” They both can visually access the work. That’s why I made these paintings, and then I made this central sculpture, which is the shark. I designed the environment where all these things will live together, which then pushes this presentation into more of an experience. I want it to be transformational, I want people to walk off the street and walk into this flooded room. During the opening, when you’re in a room full of people and we’re all in the flood together, you look to the person beside you and they are helping you stay afloat. They’re helping encourage you. I wanted to face my fears, and that’s why I designed this room so that I can look at the shark, this shiny, glossy, sexy objects, this—

ADAMS: Provocative.

ITO: Yeah, provocative avatar. The sharks have to constantly swim or else they don’t live. They’re always on the hunt, always on the move. And if you’re not a shark, what are you? You’re the prey, and you’ve got to just live your life and stay safe. At this point in my life, I’ve been asking those questions like, “Am I a fish or do I want to be a shark? What’s my operation? Maybe I’m a shark to protect my family, but as a citizen of the world, of the universe, I want to be one with the school of fish.” These are decisions that I’m addressing. And it’s a totally different experience when someone walks in during gallery hours and they’re by themselves.

ADAMS: Totally, yeah.

ITO: There’s no camaraderie. You’re alone in this big ocean surrounded by these paintings, just waiting in the middle of the room is this shark. It could be a representation of someone who doesn’t feel safe in their house or their place of work or place of worship or even just walking down the streets of New York. I know things are tense out there. I want people to see it, to address it, because I feel like I don’t feel safe when I live in the mirage of life. Most people tend to live in the mirage.

ADAMS: It’s kind of what they say about L.A.

ITO: Totally, dude.

ADAMS: It’s a mirage in some ways because there’s a certain level of grit that happens there, but it’s presented as a level of chill. There’s an underlying competitive pressure that you have to pretend doesn’t exist. Everything is about being chill, but when you think about the world in general, and especially the United States, in the art scene, there’s a competitiveness that is transferable to any city regardless of the fast pace of New York. I think that artists in L.A. want the same thing that artists in New York want. They want to be able to live off their work and to be able to have a studio and have a life and exist in a way that will be beneficial for them to do their survival.

ITO: I’m learning these lessons right now. My family, my practice, these things complete me. Everything else that I put so much time into, they don’t complete me. They’re part of the mirage. Right now, I’m ready to let go of it, so I can live my fulfilling dad life and focus on my studio.

ADAMS: You have other parts. Now, you’re just really working with what you have at this point.

ITO: Yeah, because life felt so cluttered. We just hold onto everything. I’m also a little bit of a hoarder with my art studio stuff, so if I bought something with the intention of using it, I’ll probably hang onto it forever.

ADAMS: Same here. I do that all the time.

ITO: I’m learning. I feel like I’m really evolving as a person. Even though these paintings seem a little heavily soaked in fear with this flood imagery, there are bursts of hope when you want to look for them. On top of the bookcase, you’ll see the soil and the plants gathered on top of that bookcase. At the bottom of the painting, it’s the depths of fear, and as you push upward into the paintings, it’s what uplifts you. It’s the forcing through a difficult time of the waterline, that transition of letting go of an addiction to breed a better life. With my parents, I was the artist. They were pharmacists. I was rebellious. I just wanted to do my own thing. But now, it’s funny, because when I talk about my daughter, Karen’s like, “Oh, maybe she’ll become a singer.” In the back of my head, I’m like, “Well, what else is she going to do so she can be secure?” It’s a full circle. Those lessons are pulling me through, out of this flood. But if I turn around and I face it, I feel like I’m more in control. That’s what I’m doing with the show. I do have a little nervousness inside of me about showing in New York for the first time.

ADAMS: You’ll be fine. It’s really good that you’re having this moment to come to New York to be able to present your work in this way. For people who’ve seen your work online or in L.A. to get to see your work here in the context of this urban landscape it will transport them into another mind frame. Color is such a major part of just the way that the work is constructed. And that’s one thing that we didn’t really get into. How do you think about color?

ITO: A lot of these colors that I’m using are the exact same colors that I started painting with when I was an undergrad. I repeat the colors. My grandfather worked at a produce shop back in the day, so they used to hand-paint all the prices and stuff. He’d have these cans of house paint that he’d keep forever until the can was either dried up or the paint went bad. For me, I love how he took these discarded colors and used them to craft these signs. My palette is a collection of colors that I’ve collected over a long period of time. They all have different names, and it’s all house paint. If I could take this domestic paint that people toss on the sidewalk and take my precision and technique to transcend just being house paint into being this painting, even though I can’t control the world around me, I can know for a fact that I’ve touched every single edge, every single square inch of that painting to perfect it as much as possible. It’s all colors that I found at Home Depot, paint that isn’t fancy. That’s how I approach colors. So these colors are really echoes and memories of previous artworks and previous experiences and memories that I have when I’m building out my color library. When I run out of colors, I have a folder that has all the colors I use, and then I can just go and get it color-matched and then I can have a fresh gallon. So these colors, they relive multiple lives.

ADAMS: They’re part of your language.

ITO: Yeah, it’s part of my language. Just like my symbols, they get used and reused and re-contextualized. It’s amazing to me how I can use the same symbol and it tells a story and it reminds me of a previous painting or a previous situation I put that symbol in, and then I can breathe new life.I like to use these pre-structured symbols and their meaning, but also put my own twist into them. I’m a creature of habit. Most people don’t get to hear this, but when people look outside in, I just want them to know that the colors are used and reused throughout all my bodies of work. They’re all part of my keyboard of colors. And with that keyboard, I can say anything I want as long as I know what color does what. It’s a way to offer points of connection with my viewers to access the themes that I’m addressing.

ADAMS: I totally get that.

ITO: For me, there’s two rounds of revisions. I have my initial idea, I lay it out, I start filling in the color. If there’s a couple color choices I want to change, I change them and then I have to finish it. There’s no more messing around. I complete the work, learn the lessons, and move on to the next one. So this show was taxing for me. I was bombarded by so many challenges from life outside of my artistic practice, like family health issues, financial worries.

ADAMS: The norm, the norm.

ITO: Yeah, the norm.

ADAMS: Those types of challenges add to the complexity of what we see. And when artists are dealing with those challenges, they’re still able to come through with a strong body of work. When a piece is successful, they become embedded in the way that the work is perceived, in the way the work is embraced or read. Those things are innately part of the DNA of each artist. Again, it was a pleasure speaking with you. I really enjoyed hearing about your work.

ITO: Thank you. It really means a lot to me that you did this because I have been following your work for a long time. I really love just the ideas around your work and how you process it and you being based in New York. I just really want to offer my sincere self to New York, not like this shiny artist persona.