WALK THROUGH

How Poetry Inspired Artist Lotus L. Kang’s Uninhabitable Greenhouse at 52 Walker

Lotus L. Kang’s images are objects, her objects are performances, and her performances are cinema—which is, of course, moving architecture. Maybe I’ve got that wrong: things aren’t other than what they are, but rather matrices of mediation both social and material. “I think it’s a way to deconstruct a medium, and think about the substrata as this non-neutral contributor to whatever it’s holding,” Kang says of her recent work in Already, her solo show now on view at 52 Walker in Tribeca.

The Toronto-born, New York–based artist’s practice defies settled positions: draped sheets of photo paper are often left unfixed and light-sensitive, and many recent sculptures feature precisely engineered motors and symphonically composed lamps. To experience Kang’s multi-material is to experience transformation itself—a process both playful and haunting.

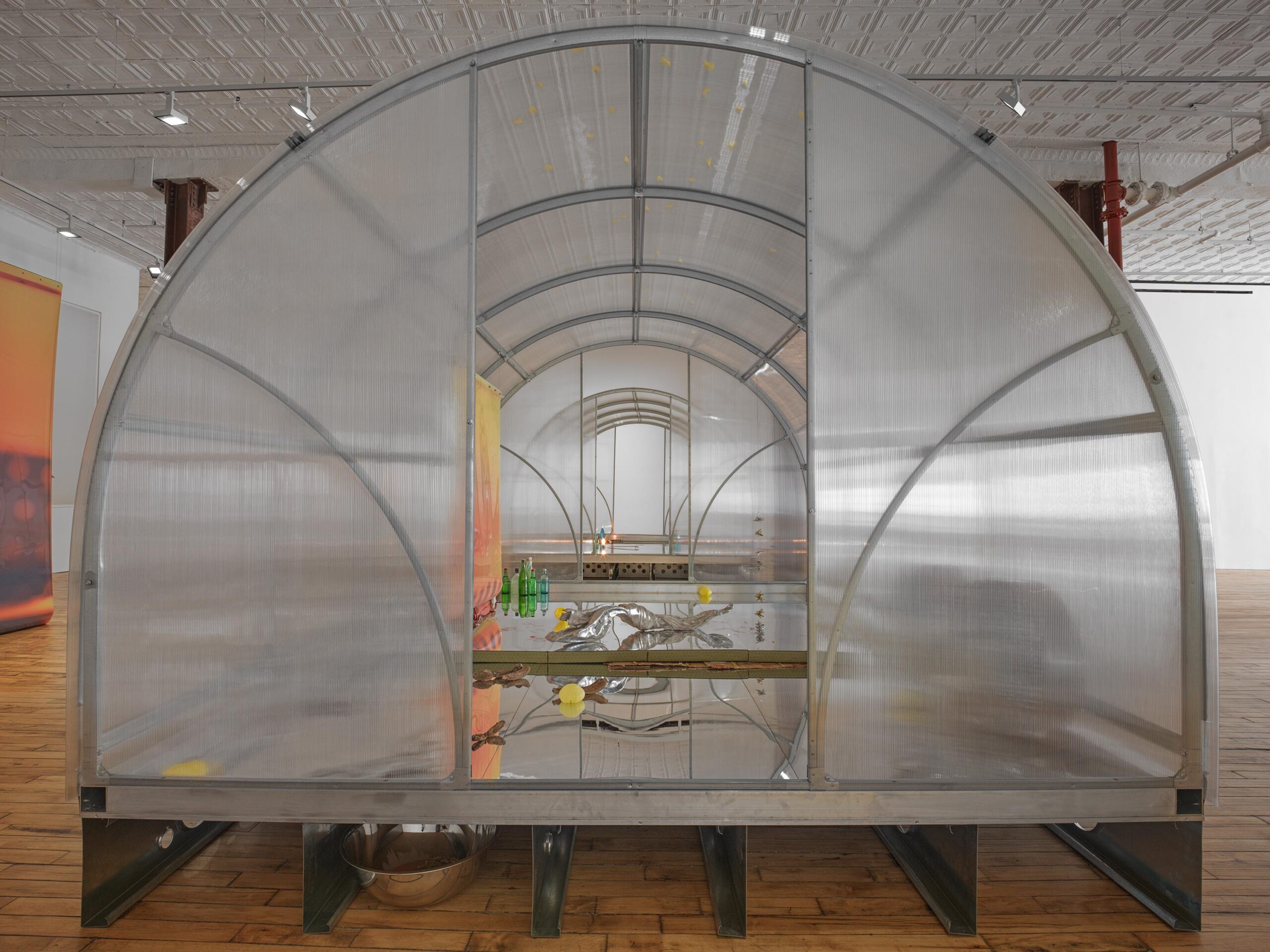

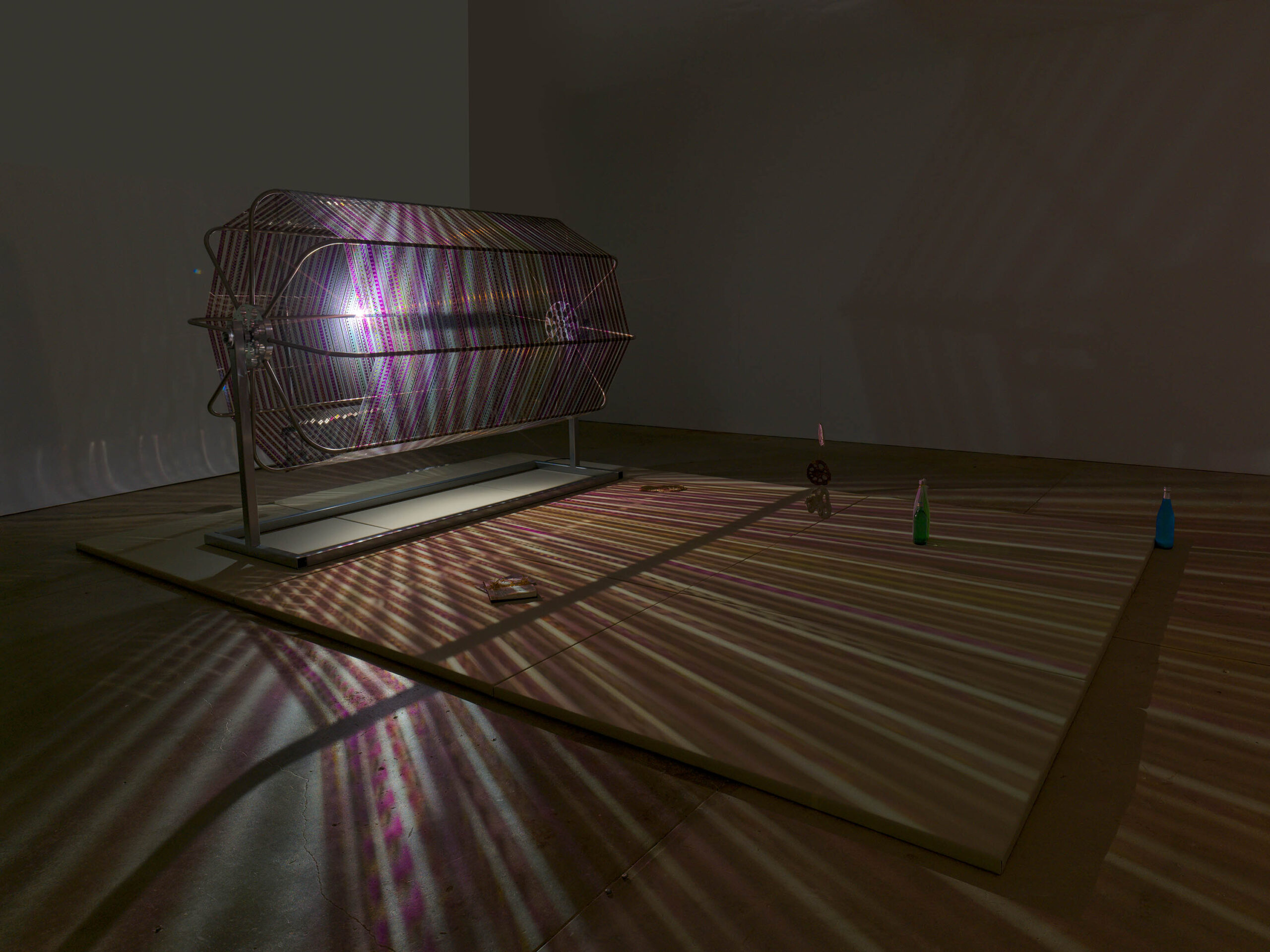

Kang has exhibited at galleries and institutions across the world, including the traveling solo show In Cascades (2023–24) at the Chisenhale Gallery in London and the Contemporary Art Gallery in Vancouver, and in the most recent Whitney Biennial. Already is perhaps her most expansive exhibition yet. It features greenhouses hosting cast-metal anchovies, celluloid filmstrips (lit by a rotating lamp-armature), and colorful bottles of spirits; drawings pasted with studio scraps; hidden photographs; ceramic new-born birds; and a gobsmacking kinetic sculpture-film in the gallery’s basement called Azaleas II. That sculpture takes its title from a poem by Kim Sowol. Poetry, as I discovered while walking through the exhibition with the artist earlier this month, pervades these works.

———

DREW ZEIBA: So what drew you to the greenhouse? When did you start working on them?

LOTUS KANG: Well, the first greenhouse I made was in a field outside of Toronto, where I was living at the time and where I grew up. I built it after this residency I did, which was in this massive studio filled with light, and I got to tan all this film. It was really game-changing for me. And when I came back to Toronto I was like, “How do I emulate a studio that’s full of light, where I can really enact this idea of the process as the work?” And the greenhouse just came to me as an idea. So it started there in 2022. It’s been a few years now of sitting with it as this tool that I use in my practice that’s often invisible, and then making it visible.

ZEIBA: You have one in Catskill that you built, right?

KANG: It’s in Wood-Ridge. It’s on Denniston Hill’s property, they’ve been very generous. It’s this same model without this joist, obviously. But this is 13 feet, and the one at Denniston Hill is 22 feet.

Installation view, Lotus L. Kang: Already, 52 Walker, New York, April 11–June 7, 2025. Courtesy 52 Walker, New York.

ZEIBA: Do you think of these as two separate objects, or as single objects?

KANG: Good question. I mean, they were definitely made in contrast to each other, because my work is so responsive. They have separate titles and materials and lists. They are listed as separate works, but to me, they came into being together, and thinking about one is full and one is quite empty, one is still and one is moving. One has these 49 objects and one translates this performance of 49 objects. So they’re kind of playing with the time scales in different ways. So because I work within an installation form, for lack of a better term, it’s maybe “environment making,” without it being something immersive to the point of spectacular or spectacle.

ZEIBA: When you say you “work responsively,” what do you mean?

KANG: I say this because “site-specific” to me has always had some kind of connotation towards a fixity. I like thinking about responsivity versus specificity, and in this particular space, it was really these pillars. That really split the space, and kind of doubled it. Building a wall here, you only get 25 feet. And it’s not in one’s best interests to cover up what’s there. I never want to feel like I’m trying to hide a space. It’s this balance of working with what’s happening, and then also creating my own environment within that. So that really became the catalyst of thinking about this doubled greenhouse form. And also this distance between the pillars just ended up being just a bit wider than the greenhouses, which worked out. But I wanted them to be facing each other in this way, where it’s like, “We’re not trying to hide these things, they’re there, and you’re contending with them.”

Installation view, Lotus L. Kang: Already, 52 Walker, New York, April 11–June 7, 2025. Courtesy 52 Walker, New York.

ZEIBA: On the theme of light, I’m thinking about the mirrors that recur here. You have the mirror platform over there, and—is this like a tatami mat, or something?

KANG: Tatami that’s mirrored, yeah. The mirror is a newer form, although when I was at Bard MFA, in my thesis work, I was working with mirrors as well. I was thinking of this kind of diffracted dance studio. But the mirrors were vertically hung, and then occluded in all sorts of ways. I treated them with materials and dug holes out of them. But in a very direct way, mirrors deal with time and immediacy. They mark a presence, and yet they shift and alter, diffract or distort what is there. It has an immediate presence to it, and also has everything to do with self-recognition. But in this case, you don’t see yourself right away. It also pulls the external environment in, and suspends a kind of awareness of weight and airiness. It kind of complicates the relationship to knowing something, or seeing something.

ZEIBA: You mentioned the idea of performance, and I think there’s some reference to performances you’ve done in these greenhouses. And then I’m also like, “Are these things inside the sculptures seeing themselves?” We have these metal objects lying on a mirrored bed.

KANG: This one in particular, Receiver Transmitter (49 Echoes I), is kind of like a film still to me. I wanted it to feel like there’s a recent absence or a presence. Which is, in and of itself, some kind of performance, right? I’ve been doing a fairly deep dive on Chantal Akerman and this book that was written about her work called Nothing Happens. I love this idea of everything and nothing happening at once, and the mundane as a kind of performance. I wasn’t thinking about that when I was making it, but it has some kind of kinship to those ideas. And under the tatami mat, there are images of another ritual performance I enacted two years ago. So that’s embedded in the work, but not seen. And I feel like the works themselves have an inherently performative nature to them.

Installation view, Lotus L. Kang: Already, 52 Walker, New York, April 11–June 7, 2025. Courtesy 52 Walker, New York.

ZEIBA: I’m wondering a little bit about the relationship to film or moving image. How did you start playing with that?

KANG: I was always interested in going to the substrate of something. I wouldn’t really call it a root layer, but somehow backing things up. To understand that we’re still dealing with a material reality that has all sorts of implications within it—celluloid or film as a material form. So it’s a way to deconstruct a medium, and think about the substrata as this non-neutral contributor to whatever it’s holding, as well. And with film, there’s an incredible opportunity to play with time stretched out, and kind of expanded, but also extremely condensed at the same time. I’m trying to layer those timescales together, because that’s how we exist as bodies.

ZEIBA: I read that you came to this material, Fujiflex or Duratrans, by accident the first time?

KANG: Yes, it was an accidental encounter, which so much of my work is, like the greenhouses. It was gifted to me by a photo house when I was taking their scraps. They thought they were giving me expired paper, but it ended up being this film. That started it off, but I’m still figuring out what it’s capable of. It’s a highly experimental process.

ZEIBA: What’s your process of experimenting with it like now?

KANG: I start in the greenhouse. The wooden pallets they sit on are a necessity. If I hang the film and it hits the floor, I put a drop sheet down because things grow in greenhouses. I elevate it on pallets because of flooding from rain or snow. The pallets started indexing themselves onto the film, which I was interested in as an index of horizontality. I’m slowly pushing things by making my own pallets that echo these holes, or bringing joists into the greenhouse. I’m starting to bring sculptural aspects into the work, like a chime I hung in front of the window. The fabric in some was out of necessity, but has become intentional. The greenhouse gets wildly hot when I’m in there, especially during summer. I go in with nitrile gloves, which make you sweat profusely, put on a cap, and I’m in there for over an hour doing semi-physical work. It’s so hot that my Crocs shrank. So I’m trying to make quick decisions before I lose my mind. The fabric came out of necessity because this film is plastic, polyester. When i’’s this hot and the film is touching itself or other sheets, it starts to melt. I introduced the fabric as a membrane, and that necessity has now become part of the work. That’s what I mean by “experiment.” I’m figuring out what variables I have to makeshift. Many things in my practice feel very makeshift, and those solutions end up opening up to something.

ZEIBA: But then you have this high-polished aesthetic. It doesn’t look industrial, but you use industrial elements like joists or spherical bolts. They’re perfectly smoothed over parts, but you can still see that joinery. There’s a push and pull.

KANG: I like that contrast, the idea that you recognize the roughness through its opposite. It heightens focal sensations. The drawings have a looseness where you can see my hand in them. I undo the imagery a lot. I start and almost throw it out, thinking it’s the worst drawing I’ve ever made, and I have to return to it weeks later. I undo it, add layers and objects, and then it becomes this thing. But it’s loose. Then I contrast it with something like a beautiful chrome frame. The precision is not done in my studio. Actually, everything there is very imprecise.

Installation view, Lotus L. Kang: Already, 52 Walker, New York, April 11–June 7, 2025. Courtesy 52 Walker, New York.

ZEIBA: Do you ever actually throw things away? When is it in the process that you have something you want to throw away but stop yourself?

KANG: I’ve been getting better at waiting longer. It takes a few years until I realize something isn’t going to work out. I’ve moved with bins of things, bags and little objects or materials that I keep feeling I can make a work out of or that are still interesting to me. I collect things I encounter in the world, then I might source a more industrial scale of them. Like these mesh bags that are everywhere and fascinate me. This green paper is ripped-up paper that would normally hold pears in a grocery store.

ZEIBA: Should we talk about death? Death is a big part of all this, right?

KANG: It really is. Yes.

ZEIBA: The title of the show [Already] comes from a Kim Hyesoon poem. And it’s also a reference to some Buddhist traditions around death?

KANG: Yes. The book has 49 poems, referencing the number of days a spirit is believed to roam between death and rebirth. You would make many offerings, ceremonies, and rituals. I’ve never practiced it, but I’m interested in it as it relates to inbetweenness, bringing supposed binaries together. I find it cathartic to think there’s a guided passage between these things. The book was written in response to the Sewol Ferry disaster in South Korea, where over 300 people, mostly students, died when the ferry sank. At first the government tried to cover it up, saying everyone survived. I think she wrote it in a state of extreme grief. She’s been a teacher for a long time, so she has a relationship with the youth and next generation who continue our thinking and being. But she also wrote it in a state of rage against governmental structures that have no actual care for the people, rooted in Korea’s history of imperialism, neocolonialism, and colonization, especially by the US which still has a military presence there. I’m amazed at how a poem can contain these many layers of history, the way the films contain layers of time and space. One object I included, which most miss but is on the checklist, is this bottle of American Soju I found online. When I put it in the checklist, I call them “spirits,” connoting both something that passes through your body and something you carry with you as an offering.

ZEIBA: That label’s fucking crazy.

KANG: It’s on the Taegeukgi, the Korean flag. It’s wild. I’m interested in found objects. I was looking for other bottles of spirits online and came across this. I knew I had to work with it, but it couldn’t be regarded the same way as these.

Installation view, Lotus L. Kang: Already, 52 Walker, New York, April 11–June 7, 2025. Courtesy 52 Walker, New York.

ZEIBA: The American Soju bottle is a little too loud.

KANG: Yeah, but it’s a way to recognize these layers of time and history as well.

ZEIBA: Are these actual ginkgo leaves?

KANG: Yes, they are actual leaves that I coated with acrylic medium. I went to Seoul last fall while working on the show, thinking it would completely inspire and change my understanding, that it would make the show. It really did not. I felt this gap everywhere I went. This was me trying to find answers in something that was never going to fulfill it. Nothing was inspiring the show. But that was important too. I thought I had no show, but there were these beautiful ginkgo leaves everywhere, like a shedding death. I painstakingly collected and pressed so many in the Airbnb I was staying in. When I got back to my studio in Dumbo, there were ginkgo leaves everywhere. It’s hilarious because yes, they are from Seoul, but they could be from anywhere. I like that play between hyper specificity and ubiquity.

ZEIBA: It makes sense now that they’re next to the American Soju.

KANG: And that’s Kim Hyesoon’s book open to the poem “Already.” This old work from 2022 was once shown unfolded and now it’s latent in there.

ZEIBA: Have you read her translator Don Mee Choi’s book DMZ Colony?

KANG: Obsessed. And Hardly War?

ZEIBA: I haven’t read that one.

KANG: That one’s amazing. She wrote it during her residency in Berlin, part of a trilogy with DMZ Colony. In Hardly War she speaks through multiple times and spaces that interact and intersect. It was super inspiring for me.

ZEIBA: I should read it. Have you worked with poetry before directly in your work like this?

Installation view, Lotus L. Kang: Already, 52 Walker, New York, April 11–June 7, 2025. Courtesy 52 Walker, New York.

KANG: Not so directly. The first Azaleas work I made dealt with a historic poem. I’m relatively new to actively reading poetry in the last five years. It happens at different speeds, fast and slow. You have to read it multiple times. It’s challenging, not the same satisfaction as theory or fiction. But it’s evocative and haunting in ways other forms of writing can’t be.

ZEIBA: Have you read this Kim Hyesoon poem, “A Floor Is Not A Floor”? I’ve read it so many times. The first time, it sounded like baby talk, its affect was silly or funny with all these exclamation marks. But then you realize she’s talking about death. It’s doing so many things at once, it’s impossible to have the same reading twice, and not just because you’ve read it before.

KANG: Exactly, and that will change with time too. The context of that book is the condition under which it was made. It’s in there, similar to the unseen performance informing the work in a deep way. Her work is very surreal, grotesque, with so much “mommy, mommy” in it.

ZEIBA: Literally “mommy, mommy.”

KANG: It’s very intense, which is where I think the baby birds come in.

ZEIBA: Oh yeah, should we go look at them? The baby birds?

KANG: Kim Hyesoon and many other poets use a lot of bird imagery. I was initially drawn to them because I’m not a huge bird person, it’s never been the animal I’m most drawn to.

ZEIBA: Have you seen that show at the Met right now with Chinese porcelain made for the European market in the 16th through 19th centuries? It’s in the octagonal rotunda downstairs.

Lotus L. Kang, Azaleas II, 2025, installed at 52 Walker, New York. © Lotus L. Kang. Courtesy of the artist and 52 Walker, New York.

KANG: No but I can’t wait to see it. Anne Anlin Cheng wrote Ornamentalism about surface and ornament as standing for Asian female subjectivity, or yellow woman theory. That’s been on my mind for some time as a back layer, maybe less immediate but part of my draw to a material like porcelain. But the baby birds were mostly because they’re these desperate things.

ZEIBA: What’s crazy is these porcelains make the parent and the baby birds the same color. Most baby birds look like weird gray, abject, see-through fluff balls that can hardly hold their head up. They’re not cute.

KANG: Previously I’ve made cast glass baby rats in an installation. Those provoke more of seeing a baby thing and being drawn to it, then inherently repulsed at the same time. This overall is a bit more tender than the rats were. These birds are always looking up and they eat barf. They’re containers for holding cycles, holding other bodies in their body.

ZEIBA: It’s doubling down on parenthood. “Not only have I reproduced you, now you’re eating stuff from my stomach.” It’s this constant generational passage.

KANG: Yeah, a kind of passing of an orifice or boundary that unites them.

ZEIBA: Which is again this inside/outside, these thresholds. The fact you can’t go in the greenhouse, but you can fit your head in.

KANG: I keep talking about them creating intimacy through distance. The fact that you can’t enter still pulls you in. We talked about if people should be able to enter them and it was no. I kept thinking about how to make it immersive without sensationalism or spectacle. It has to ride that line where you are not getting an experience, I’m offering you to enact your own internal experience.