Derrick Adams’ Cultural Collage

DERRICK ADAMS IN BROOKLYN, NEW YORK, APRIL 2016. PORTRAITS: CHRISTIAN HÖGSTEDT.

Brooklyn-based artist Derrick Adams is unabashedly captivated by popular culture. The Baltimore native culls content from television commercials and YouTube screenshots to fuel his multidisciplinary practice, which includes photography, performance, sculpture, and collage. With a BFA from Pratt Institute and an MFA from Columbia University, Adams has a firm academic grounding, yet his works predicate themselves upon openness, playfulness, and the potential for participation. Though he admits his work consistently changes, the participatory aim remains the same: “You have more of a direct response from the audience when you make works that are engaging with what they know and how they feel,” he says.

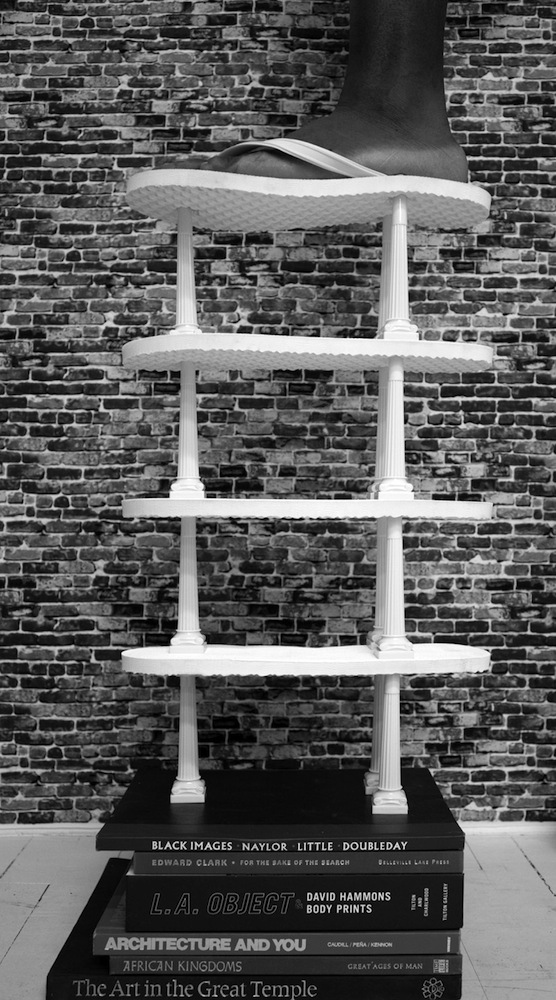

Beginning Friday, Adams’ recent photographs will be on display at 1:54 Contemporary African Art Fair at Pioneer Works, coinciding with Frieze New York. The black-and-white images act as a contemplative introduction to ideas that Adams wrestles with in the works he’s creating for “ON,” a solo show opening at the same space this summer. With “ON,” Adams will transform Pioneer Works into a vibrant ground for performance; his six-foot tall fabric wall hangings—consisting of dashikis, vivid fabrics, and mass-produced graphics like polka dots—will serve as the stages before which performers will improvise archetypal African American roles from television (such as a basketball player promoting a cereal). Adams will serve as the emcee, controlling “who is cancelled out and who is turned up” during performances on the show’s opening night, and a film of these performances will screen for the duration of the exhibition.

“The objective is not necessarily about the product itself. It’s the idea of the representative of the product trying to connect to the audience,” he explains of his interest in the commercial structure. “It’s about the dramatic roles that black characters have on TV. I don’t think of that as a negative or a positive; I think of it as a construct to look critically and understand—Is it a necessity? Is it a formula? Does it work? Does it not work? I enjoy some of those characters, but I look at them critically as well as for entertainment,” he continues. “I think it’s important to know television and to understand it as a form of entertainment.”

We visited Adams at his studio in Bed-Stuy, Brooklyn, not far from Fulton Street, where he purchases many of the fabrics used in his collages.

HALEY WEISS: Television is an interesting medium in that most people who watch commercials don’t critically interrogate them in terms of representation. I don’t think people realize the power of images to control perception of the self, especially in relation to how you view other people.

DERRICK ADAMS: They don’t—that’s kind of the objective, for people not to think that [way]. If you start thinking that it goes against the medium itself; the seamlessness of it is for the viewer not to think critically. For a viewer to actually step outside of that and look at something a different way is an unintentional, unexpected response on a producer level. The whole idea is that they make it easier for you, so you don’t have to scratch your head to think about it.

The success of television is that it makes the viewer feel a certain way without them even knowing that they’re being manipulated. I think that art does [that] successfully. One of the things that fascinated me about undergrad and studying art history and the Renaissance was that with the religious paintings, they were more focused on the illiterate and the people who were not as [art] savvy; it’s the same thing with the media now. The church was like a big HD television for people. I was always fascinated with the power that artists had at that time to create these illusionistic structures that mimicked reality around them in some way, and were able to get emotional responses from people and enlighten them about things they thought were important. In our generation, television has that same godly presence; it’s always there, always visible, seeing you as much as you’re seeing it. It’s this thing in the space with you. Now that people are trying to get rid of the frame of the television, it’s making it almost like a virtual space… You think of it as a person or something, which I guess is the intention—to make a person feel like they’re not watching television.

WEISS: How do you think television informed your understanding of the world or sense of self when you were younger?

ADAMS: It was a big part of it. I became more critical and reflective of the whole TV medium as an adult more than as a child. As an adult I started thinking, “Who am I? Why do I like certain things? Why do I think certain ways about certain things, people, and foods?” I started revisiting what I used to look at as a kid and some of the shows that were on TV, and I realized a lot of those things are the reason why I think or feel a certain way. It’s not always negative but it’s definitely an imprinting structure. For me as an artist, going back and looking at it and making work that reflects it actually helps me highlight things some of the things that I think were important to the making of me or my generation. I also subtract things that I feel weren’t as productive or positive.

YouTube is really interesting because you can look at the clips of what you liked as a kid. You can see that five-minute scene, which makes you think, “Other people are thinking of that scene too, because someone put it up there.” I know movies that I watched as a kid and my parents watched that they know all of the lines to—they use it in their communication to each other. Some of my family members use scenes from The Color Purple in their daily conversations and everyone knows what scene it is, or Harlem Nights. TV and media become this material that people use to communicate with each other on a day-to-day basis. I don’t have to go all of the way back to the way people look at the structure of Modernism or the Renaissance to talk about what I’m interested in. What I’m interested in as an artist, or just as a person, is making connections with people who I feel are more challenging to make connections with, versus people who are trained to look at abstract paining or sculpture in a very formal way. I think you can make work about these characters or characterizations of blacks on TV and still make a universal conversation because TV is about universality. If you’re going to use any representation of a black figure in a context that is accessible, TV to me is the most accessible when you think about output.

WEISS: When you buy these fabrics on Fulton Street, do you tell the people that you’re buying them from what they’ll be used for?

ADAMS: Sometimes they think I’m a fashion designer. I show them pictures on my phone of what I’ve done and they’re blown away like, “What? You did that with this?” The kind of stuff I buy is so sporadic and diverse so sometimes other customers ask me, “What are you doing with this?” Especially the older ladies who go there all the time to buy fabric, they’re always very curious [about] what I’m doing and buying.

After working on the smaller collages and painting, and incorporating the fabrics, I became really interested in the type of fabrics that I select and the kind of things I’m interested in that are already manufactured by companies, how those things look next to each other, and how that’s a language in itself. That shows more of my psyche, of what I think is interesting and what I don’t think is interesting, because I’m not painting on it; I’m just taking swatches and combining them to create a tension, almost like an artist [doing] hard-edge painting—I’m just doing it with fabric.

WEISS: What’s the most surprising or insightful thing someone from outside the art world has told you about your work?

ADAMS: “I can feel this.” People tell me that. I like that, that’s what I want to do. You don’t have to explain it to me. I like to hear that more than, “I like the colors.” If an artist who I really admire sees my work, they’ll say, “The composition is spot on,” or they’ll say, “It reminds me of [Robert] Motherwell.” You’ll hear that from an art person, which is cool, and is a compliment in the highest regard if you’re attached to someone who has created an area in art history that is totally their own. If you’re lucky to be compared to the older and more established artists I definitely feel like that’s a plus, but the other thing, the “I can feel this,” is even a bigger success—to have someone come in and say, “It’s fun.” I had my nephew come into my studio the other week and he was looking at my work. He’s six and I was explaining to him what I was doing, and he looked at me and said, “That’s fun.” It can be just fun for some people. I think the success of art is that it means different things to different people, and different people respond to it in different ways.

I love popular culture and how people are so responsive to it, especially this generation. They look at pop culture as just as significant to politics, which is kind of disturbing, but it’s what’s happening. Political figures are less significant than pop figures, and pop figures sometimes have more ability to change people’s minds than politicians. What’s really interesting about pop figures is they can be a very non-political person in daily life, but then they might do a seemingly political video or TV show, and people think of that as their real response to what’s happening in society versus them being a persona and just acting out. People think that performing politics is being political now. No one ever questions if it’s based on a corporate structure or sales—things that aren’t necessarily on the surface. People don’t question; they’re not suspicious. I’m always suspicious. That’s definitely something to think about when you think about audience, and what they see, and what they believe to be real or not real. That’s the same reason you’ll see a Trump character that is on television being seen as believable. People see him on television and think that’s who he really is. People look at people on television and think that’s how they are.

But no entertainer is a free agent. When you see a person on television saying something or doing something, they have writers, they have structures of conversations to have, they have key points to can go over, they have stylists that put clothing on them—what kind of tie to wear, what kind of dress to put on. It’s a totally different structure on TV that most people are unfamiliar with, and some people just don’t want to know because it’s too complicated to think about. The complication actually implicates them more in their lack of knowledge, and some people don’t want to be looked at as stupid. If you’re comfortable in not knowing, you can actually succeed at some point. But sometimes knowing too much can also stop you from getting somewhere.

WEISS: What does it mean to you to show your work in the context of 1:54 Contemporary African Art fair?

ADAMS: I tell people all of the time, “What’s more contemporary African than an African-American?” [laughs] There’s so much history attached to the discussion about, “Are we African? Are we not African?”—like the group Dead Prez says in one song: “I wasn’t born in Ghana, but Africa is my momma.” One of the benefits of the art fair and the future of it is extending out what contemporary Africa is. It’s a market-driven fair but it’s also an opportunity to talk about history and value in the same way. It’s interesting that there are a growing number of younger contemporary African artists that are exhibiting alongside African-American artists. I think that the relationship between us, as artists, is growing and developing because a lot of artists of color are traveling more and getting bigger exhibitions where those questions are coming up.

As a black American artist, it’s a really interesting conversation to show some of the imagery in my work versus what’s coming out of the [African] continent from the artists who live there. My relationship with Africa is based on storytelling, historical documentation, and things like that. Even my disconnect with the continent as an American is a romantic relationship because everything around Fulton Street is based on that: the dashiki, the African products around the corner. All of those things are really geared toward African Americans who feel a desire to be reacquainted with their culture. You don’t see Africans around here wearing the dashikis as much as you see African Americans wearing these things. It’s a positioning of African Americans saying, “I’m African too. I may be in this country and I may be a part of this country, but I still think about my culture.”

1:54 CONTEMPORARY AFRICAN ART FAIR OPENS ON FRIDAY, MAY 6, AT PIONEER WORKS IN BROOKLYN. FOR MORE ON DERRICK ADAMS, VISIT HIS WEBSITE.