STUDIO VISIT

How Artist Mark Leckey Found God in the Glitches

Mark Leckey, photographed by Alessandro Raimondo.

In Mark Leckey’s heaven, the angels use autotune. The 61-year-old English artist and Turner Prize winner grew up in the ancient town of Birkenhead, immersed in working-class counterculture. He remains a connoisseur of folklore. His breakthrough work, the rhythmic found-footage documentary Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore (1999), honors the suburban glory of the British rave scene. More recent videos push vertical smartphone footage—of a kid smashing a bus shelter, for instance—to the point of religious ecstasy. Carry Me into The Wilderness, a pandemic-era work for a superstitious time, features audio of the artist coming down from a recent spiritual encounter, layered into an otherworldly digital chorus: “I can’t fucking bear it / it’s just fucking overwhelmed man / what the fuck ah oh jesus / ah ah god oh oh.” On the occasion of Leckey’s largest survey to date, opening September 11th at the Julia Stoschek Foundation in Berlin, we projected into each other’s apartments via Zoom to discuss the coming kingdom of god on earth.

———

TRAVIS DIEHL: Thanks for taking a minute, it’s good to speak.

MARK LECKEY: Yeah, you’re welcome.

DIEHL: I wanted to talk mostly because I saw your show at Barbara Gladstone last fall, and I was really impressed by it. The diptych you had going with the bus stop piece and the hermit piece, and the gilded kind of video… It really felt very timely. In a way you’ve been investigating technology, mysticism, folklore for a while, but in those pieces it felt like you were addressing divinity a little more directly. In the voiceovers of both of those pieces there’s these moments where it’s just, “Oh, God. Oh, Jesus.” I wanted to start there.

LECKEY: Yeah, it’s always a good place to start with, divinity, right? [Laughs] I mean, I made both of those pieces towards the end of lockdown. And I’d just been reading a lot about—I haven’t had to say this out loud so I might say it wrong—but millenarianism?

DIEHL: Yeah. Doom and gloom, apocalypse. [Laughs]

Carry Me Into The Wilderness, 2022. Film Still. © Mark Leckey. Courtesy of the artist and Gladstone.

LECKEY: No, doom and gloom, and then salvation.

DIEHL: Right, for some.

LECKEY: It’s like a “Kingdom on Earth” at the end. Anyway, it was just this thing I was reading about a kind of millenarianism that was evoked at the end of the pandemic. It’s already been forgotten, but there was this idea that it would wipe the slate clean, or we would be more empathetic or understanding after all of it, and we could kind of restructure the world. But it lasted so quickly, it was ridiculous. Anyway, I made it when I had read that and I thought, “Oh, yes.” I think I was feeling some of that in a very kind of viral way.

DIEHL: A viral way?

LECKEY: I mean, it wasn’t coming from within me, it was coming from outside. I was picking up some vibrations or whatever. So, when I look back at those pieces, and in particular that one Carry Me Into the Wilderness, I had a moment where I entered into something that felt sacred. It felt like it was a divine, mystical experience on a quite low-energy level, I’d say. But still, I was annihilated in this municipal park.

DIEHL: So, it’s this kind of experience of wilderness or nature?

LECKEY: Yeah. I mean, it’s a very kind of circumscribed nature. It was basically a local London park. But in the middle of it, with the sun shining through the leaves, I had an encounter. I mean, I could have interpreted it many ways, but I wasn’t necessarily thinking about this stuff prior to it. But it seemed to fit the most: the idea that I’d entered into some kind of sacramental reality or mystical experience is the best way to describe what happened to me.

DIEHL: Is that your voice in Carry Me into the Wilderness, and is it capturing that moment?

LECKEY: I’m walking through the park, and I’ve got my phone. This feeling comes upon me, and so I kind of spasm towards my phone because something’s happening, right? [Laughs] I’m having an experience, so I reach for my phone and just record the come-down. What you are hearing there is me coming out of this experience.

Carry Me Into The Wilderness, 2022. Film Still. © Mark Leckey. Courtesy of the artist and Gladstone.

DIEHL: I think why I’m drawn to these expressions of ecstasy or spiritual experience is because it feels a little bit radical. This is a cheesy reference, but Jeff Mangum from Neutral Milk Hotel has this quote about how he sings about loving Jesus because that’s the only punk thing left to do. I’m wondering if you feel vulnerable talking about this kind of thing, or admitting that you had an actual spiritual experience—not in an academic way, but in a very sincere way.

LECKEY: I mean, it’s only after 20 years of making work that I felt able to talk about these things. I hesitantly made something before with the piece at Tate Britain, Under The Bridge, which was about an encounter with some paranormal experience—with the fairy, or some kind of leprechaun under the bridge. But I’d be more circumspect about that because it was a childhood thing, so it was more of a reflection. But this was more like I had this thing happen to me, and in my process of trying to grasp what had happened, the only thing that was truly available to me was to try and make it into an artwork. To try and realize it as something that I could then sit back and watch, and that would then tell me if I was convinced or not.

DIEHL: Are you convinced?

LECKEY: Well, I talked before about virality. I mean, this was from outside as much as it was transcendent, but also a kind of feeling of imminence. I think that when we crossed over from analog to digital and we entered into this immaterial realm, it seems obvious that spiritualism would be reborn, or something that could be re-engaged with. You know what I mean?

DIEHL: Mm-hmm.

LECKEY: And the more derealized the world, and the more rational institutions collapse, then it seems obvious to me that spiritualism and religion will rush in to fill that gap.

DIEHL: Yeah. Your work has always had this element of class consciousness, or this lowbrow/highbrow tension. The fairy is a good example of folklore being something for peasants to believe in or something.

LECKEY: Children and the Irish.

Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore, 1999. Film Still. © Mark Leckey. Courtesy of Cabinet, London, Galerie Buchholz Berlin/Cologne/New York and Gladstone Gallery, New York.

DIEHL: [Laughs] So, you can say that, I can’t. It’s–whereas an art audience is sophisticated, they’re reading French theory and we’re past this state of belief or gullibility. But I think we’re living through a resurgence of that. I think about even like QAnon or the weird conspiracy theories that we have in the U.S., which–I don’t want to say it’s necessarily a lowbrow thing–but it does seem mostly that it’s people outside of cities who don’t really know what D.C. is like, who think the pizza parlor has a sex dungeon under it. There’s this insider-outsider dimension to that, and it’s kind of feudal. You’ve been working with medieval themes for a minute, but I think that is more and more manifest, the idea of feudalism as people feeling powerless, and then turning to these beliefs to regain some kind of agency.

LECKEY: Yeah, definitely. Again, this is why I started reading about millenarianism, because it seemed like these people’s crusades, peasant revolts even, are initiated by charismatic figures and embrace unreason and orthodoxy. They oppose orthodoxy in any kind of form. I guess orthodoxy in the states would be like the East Coast, right?

DIEHL: Mm-hmm.

LECKEY: And in the art world, it would be French theory or critical theory. That’d be the orthodoxy. I’ve always remained doubtful about the uses of theory, and I don’t know if it’s suppression. But I’ve always recoiled from the idea that art could in any way be part of the sciences, or that it could take in any way a dismantling critical approach. I was thinking the other day about this idea of the medieval and the fear of feudalism. But I think the medieval is beyond us. It serves the same function as nature. It’s outside of us. But I think what’s happening now in terms of A.I. and all the rest of it is a spiritual quest. It doesn’t understand itself as that, it understands itself as purely rational and technological, but its drives are very transcendental, or Neoplatonist.

DIEHL: That’s interesting. I’ve been thinking about A.I. a lot, obviously. I’m also thinking about the “bus stop piece.” You used A.I. in that editing, right?

LECKEY: I didn’t. The thing is, the bus stop is never complete. I can’t remember the version I showed in New York. I might have tried some A.I. in that, maybe a little bit, but with not very satisfactory results.

DIEHL: So it’s not something you’re working with or excited about?

LECKEY: Well, I’m not excited about it. [Laughs] I more feel dwarfed by it than anything. But I’m interested in it as an image-making technology, because I think that’s where I come from in a way. I started making art because I was able to manipulate images digitally. And A.I. is, on an image-making level, the next step. It’s the evolution.

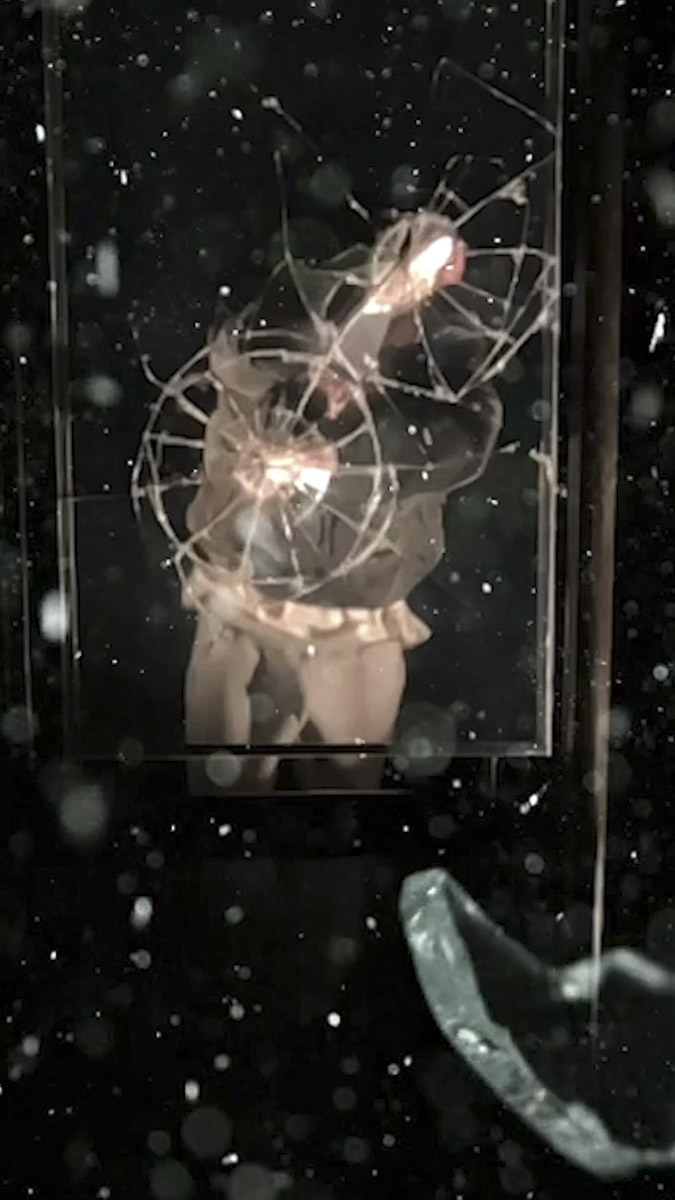

To the Old World (Thank You for the Use of Your Body), 2021. Film Still. © Mark Leckey. Courtesy of the artist and Gladstone.

DIEHL: It’s an interesting point because it’s cutting edge in one sense, but I think also from my own skepticism, A.I. is a regurgitation machine. It can’t actually invent anything, really. It recombines and makes maybe novel recombinations, but there’s a sense that it’s drawing on the past, so culture is chasing its tail, and everything is remixed. The idea of progress is a little bit lost, or feels impossible now. And I wonder where you come down on that idea: is culture stuck in place?

LECKEY: Well, when you describe this idea of A.I. regurgitating and remixing, I hear that and think, “What’s the difference?” [Laughs] When I listen to music I think, “Come A.I., bombs, and rain on pop music as it is now, because to me, it’s already that. It’s always been that. But I guess it’s a scale thing, isn’t it? Like it can be good, it can remix, but at infinite scales? I don’t know what that produces. You know what I mean?

DIEHL: Mm-hmm.

LECKEY: There’s a limitless abundance to what it can do. But in terms of what else you were talking about, for me I look at the 20th century and just see that as a very particular time that was maybe an anomaly in itself, or at least very peculiar. I keep talking about millenarianism because I’m trying to write something about it, and I’ve been reading this book called In Pursuit of the Millennium, which is about medieval millenarianism by Norman Cohn, written in 1957. But for me, it was revisited in the 20th century, and there was a drive towards the end of the millennium that created an incredible amount of energy. There was constant progress, constant decadeism, or whatever you want to call it. Things were moving because they were heading into this one place. My feeling at the moment is that they achieved it. We made the transition from analog to digital, and the digital is the realization of all that countercultural new age idealism. Do you know what I mean?

DIEHL: Yeah.

LECKEY: So, it feels like everything stopped only because it was in such frantic motion.

DIEHL: And then we got there.

LECKEY: [Laughs] We got there.

DIEHL: And now we’re like, “Ah!!” [Laughs]

LECKEY: We got there. And now it’s like… do you ever watch SubwayTakes on Instagram?

DIEHL: Yeah. Where the guy has a mic clipped to a MetroCard? Yeah. [Laughs]

To the Old World (Thank You for the Use of Your Body), 2021. Film Still. © Mark Leckey. Courtesy of the artist and Gladstone.

LECKEY: There’s a great bit where this woman’s take is: “The Earth is now flat and it’s been flat since about the year 2000.” I was like, “Yes, exactly.” [Laughs] The world became flat. I mean, she was talking about it in terms of everything being the same and feeling global, but I think it’s more like the world changed and it was a cosmological transformation. And it’s only now that it starts to become visible or felt. People are definitely feeling it. Looking at it through that lens, it seems it’s flattened and everything becomes horizontal rather than vertical, and A.I. is probably part of that.

DIEHL: What are you working on for the show in Berlin at the Julia Stoschek Foundation? Is that the millenari—I can’t say it either. [Laughs]

LECKEY: [Laughs] Yeah, no, let’s not. I’ve got to find a better way of expressing it because it’s not a good word to say. Well, it came shortly on the heels of the show I did in Paris at Lafayette Anticipations, and it’s mostly the work that I showed there. The newer work is from that show, and the show you saw in New York. And then there’s older pieces. I think it’s the most work I’ve ever shown, actually.

DIEHL: I wanted to ask about the title of the show, and one of your newer pieces, Exit Thru Medieval Wounds. What does that mean?

LECKEY: It’s sort of the idea that at the end of secular rationalism, we have to go back and enter through medieval wounds. We have to go back to that traumatic point, I guess, in order to find ourselves again.

DIEHL: Yeah, I like the comparison. It’s like Byzantine iconoclasts and a soccer hooligan. But the eyes gouging out in this really rough—I feel like it was even anucleation? There’s probably a word for it. I think there is.

To the Old World (Thank You for the Use of Your Body), 2021. Film Still. © Mark Leckey. Courtesy of the artist and Gladstone.

LECKEY: Yeah, enucleation.

DIEHL: Enucleation. Yeah, and bridging those two time periods pretty seamlessly in this very hallucinatory moment where the eyeballs roll under the seat of the bus and get all covered in crumbs.

LECKEY: Yeah. Well, that was a bit of writing that was originally for Heavy Traffic.

DIEHL: Oh, yeah.

LECKEY: They asked me to write something, and I was thinking a lot about iconoclasm. And a lot about the kind of conflict in the medieval period about whether icons were acceptable, and whether imagery representation was acceptable at all. And getting back to what we were talking about with A.I., I made it in a way out of a revulsion at the sheer ubiquity of images, and the images at that kind of scale feel kind of demonic. Or diabolical, I think that was a better word.

DIEHL: Yeah, diabolical.

LECKEY: I like that. A representation of the diabolical. I heard someone else say that and I thought, “I really feel that at the moment.”

DIEHL: I mean, we could say for the record here, for the people at home, that there’s no imagery really. There’s maybe some text bubbles, but it’s mostly captions, audio, and a black screen, right?

LECKEY: Yeah. I mean, so it went from a written piece to a radio piece, for New Models. And then I thought, “I always put everything on YouTube,” so I just made a little video for that. I thought, “Well, I can’t use images, can I, if it’s about iconoclasm?” So I kept it mostly black.

DIEHL: I’m curious what you think about—I mean, I don’t want to put it this way, but what art is for? Because you have this piece that has gone through its paces as written down, then it’s audio, and then there’s this YouTube version, and I guess some other concession or way to get it displayed in a gallery. And as someone who appreciates music and the power it has, and the different approaches, why make the other stuff? Like what is the gallery and the museum doing that other things can’t do?

To the Old World (Thank You for the Use of Your Body), 2021. Film Still. © Mark Leckey. Courtesy of the artist and Gladstone.

LECKEY: I mean, without them I guess there’s a fear of total context collapse. It’s like this sweet spot where you’re able to distribute. Or, I’m able to distribute things online—podcasts, radio, all these things can be dispersed. But I’m only afforded that because the gallery and the institution contextualize what I do. It’s almost like a FTSE index, but for stock, right? It verifies it in some way.

DIEHL: Mm-hmm.

LECKEY: It’s a kind of verification that the art world still has, obviously now to a far lesser degree. It’s diminishing, for sure. I don’t know. I try not to make art. There’s this idea in theology that you can’t approach god directly. You can only approach him indirectly, obliquely, circumspectly. And it’s the same with art. I don’t want to approach anything I do as saying, “This is art.” I mean, it’s a conceit, but it gives me license to make what I want to make. And in that sense, it allows the work to appear elsewhere. And those are the spaces I want to access. Ultimately I want music, theater, all the other things I’m interested in to gather around art. The best use I can see of art is as a ritual space. A gathering of bodies, obviously, particularly when communications are all immaterial, to find a space where you can actually come together.

DIEHL: I think that’s a great place to stop. I really appreciate your time, and we’ll have to continue over a couple of drinks.

LECKEY: Thanks, Travis. Good to speak to you.

DIEHL: Yeah, likewise.