GEOPOLITICS

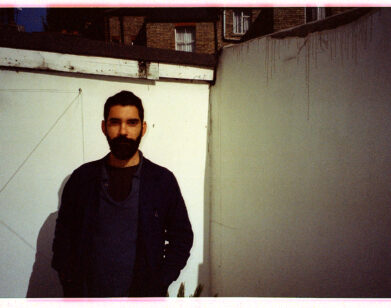

Inside David Adler’s Abduction and Detainment on the Global Sumud Flotilla

David Adler, co-general coordinator of the Progressive International, had just returned to the United States when I got a chance to catch up with him. Before that, he’d spent five days in a desert prison, where he was zip-tied, stripped, and blindfolded by the Israeli government. And before that, he’d spent several weeks as one of 500 activists on 40 vessels sailing toward Gaza as part of the Global Sumud Flotilla, part of an attempt to break the aid blockade imposed on Gaza by Israel. I wanted to ask him, in this age of political despondency, how he keeps up the fight, and how we all can learn to keep (or start) fighting against state oppression everywhere, before it’s too late.

———

P.E. MOSKOWITZ: I feel like I am meeting a hero of sorts. I was saying to a friend, “It kind of feels like how I imagine conservatives feel when they meet a veteran and they’re like, Thank you for your service.” But seriously, it’s been so inspiring to watch you guys participate in these actions.

DAVID ADLER: Yeah, I think that each of the participants on the Flotilla, as diverse as they were— grandmothers and grandfathers and doctors and nurses and school teachers—felt like they were representing much broader communities of concerned citizens, and in my case it’s Los Angelinos or U.S. Americans or Jewish Americans more generally. So many millions of people have been stuck in this well of desperation, of desolation, of a feeling of impotence in the face of such senseless slaughter. And to be able to participate in a kind of direct action, a kind of confrontation in the name of humanitarian needs and demands from the people of Palestine, was a unique privilege.

MOSKOWITZ: I’m obviously mostly interested in the politics of it all, but I first wanted to ask how you got from point A to point B. You grew up in Los Angeles, is that right?

ADLER: Yeah, and then I went to university on the other side of the country. And from there began a very long international journey in my life that brought me to places as disparate as New Delhi, India and Mexico City and Athens, Greece and Johannesburg, South Africa. In each place, either as an academic and researcher or as an activist and organizer, I was really focused on one set of questions: how do we connect the dots between these different struggles, whether it’s over housing rights or education policy or trade and international finance? How do these things in these different, really disparate contexts relate to each other

That internationalist education was very relevant to the political work we were trying to do on the Flotilla, which was to make the case not only that there is a humanitarian crisis—inflamed, maintained, and sustained by the State of Israel through this brutal and illegal siege of Gaza—but also that what we’re seeing in Palestine is connected not just politically, but mechanically, technologically and economically to what we’re seeing here in the United States. The political case we’re making is not only that we’re connected to that humanitarian crisis because we arm, aid, and abet that State of Israel, but also because the corporations that call the US home, like Microsoft or OpenAI or Meta, are directly complicit in those crimes committed against the people of Palestine. But also, the technologies that are being developed, piloted and tested over there are the same ones that are likely to boomerang back home. And I feel like a lot of people in this country are slow to pick up on what is coming our way.

I think a lot about drones, drone warfare, about how the past three years have seen a revolution [in these] repressive technologies developed in war zones like Ukraine, but also in Gaza. And I think that there’s a certain delusion about the coming revolution in repressive technologies here in the United States. In the past two years alone, we’ve seen the emergence of masked men and ICE, and that’s already a revolutionary step in the depersonalization and stripping away accountability for law enforcement. I don’t think you need to be a sci-fi author to see that what’s coming is the next phase in that process of depersonalization.

MOSKOWITZ: Right. I have a million questions about what you just said, but I think a big part of it is people not realizing that it’s not only that these technologies are coming—it’s that every problem we face here is in some way the same problem everyone’s facing, whether it’s housing or ICE or whatever. And without suggesting that Americans are experiencing one iota of what people in Gaza are experiencing, this repressive state apparatus is like no one’s friend, right?

ADLER: Yeah. And for a long time in my day job as the general coordinator of this organization The Progressive International, we’ve been making the case that we’re up against a highly coordinated, financed, and developed network, which we call the reactionary international, that is counterposed to what we’re trying to build. And that’s the combination of financiers and foundations, of astroturfed NGOs and platform entrepreneurs that are working together very effectively. And it’s called on us, I think, to look more closely interrogatively at flows of finance, at how these forces are coordinating across borders.

Sometimes that’s really obvious, as when Javier Milei, having bankrupted his country, comes knocking at the door of our treasury and gets $40 billion in bailout cash on the condition that Milei stay in power, this kind of very naked interventionism. Or in the case of Venezuela, where our state adversaries are being encircled by the U.S. Navy to try to lead a regime change operation in service of an agenda of privatization and U.S. intervention. Or the way that the United States exports a lot of its third sector, NGO, civil society organization type funding, which ends up being really instrumental in this reactionary international agenda of extraction, of exploitation, of exclusion as it advances across continents like Latin America, Africa, and even in Asia.

MOSKOWITZ: I think the kind of neoliberal capitalist bargain that Americans were accustomed to was that life was never peachy for most people, but at least that the violence that undergirds all of our lives won’t happen to us. But now it seems like that bargain is no longer in existence, right?

ADLER: Yeah, I think it was like a double bargain. So part of the bargain of being a U.S. American for a long time was that we enacted violence over there in order to sustain our protections over here. There’s also a bargain around prosperity. We know that there are sweatshops over there, and our hearts break for those sweatshops, but it’s part of the bargain that we make to be wealthy and prosperous consumers. With this radical right-wing Republican administration, we’re seeing the two key pillars of that bargain, our security and our prosperity, crumble if you’re on the wrong side of U.S. citizenship, if you’re the wrong kind of American. And if you’re the wrong kind of American, you will be stripped of your citizenship, you will be detained, deported, you will be abused, you will be tortured, you will be persecuted by this administration.

And then on the prosperity side, we’re going to rip up the contract that sought to enshrine our economic supremacy on this basis, and we’re going to make a deal, for example, with Elon Musk or OpenAI, where we’re going to massively inflate the super-profits of this capitalist class, even as the products that we consume are objectively worse than those that we could, for example, import from China. So people in China are paying $10,000 for a luxury BYD EV vehicle and U.S. Americans are going into horrible amounts of debt to go to college and get a bad education from our crumbling university system that no longer has any public funding for research, or they’re going into debt just to buy a car or a Coachella ticket.

And I feel like on the Flotilla, we were also on the wrong end of that contract. We were the wrong kind of American. And I think that that helps to explain why our delegation was treated worse by our own government than any other delegation that was present on the Flotilla. We were effectively told, “You’re on your own, there’s nothing we can or will or want to do for you, and we’re going to drop you in the middle of the Jordanian desert and you’re going to figure it out for yourself, because our interpretation of you all as terrorists is of a piece with Ben-Gvir’s interpretation of you all as terrorists.” I think all of that needs to be understood as one great redefinition of what it means to be a U.S. American in the 21st century as this project begins to crumble under the weight of its own contradictions.

MOSKOWITZ: What was it like being on the Flotilla? Did you feel a sense of camaraderie?

ADLER: So I traveled to Barcelona at the end of August with no intention of joining the actual mission. I had work to do, I had a dissertation to finish, and I was not at all planning to get on these boats. I was going there because I’ve lived and worked in Spain for a long time, and I have contacts both in the federal government and in the local government that I wanted to marshal to ensure that there was no bureaucratic sabotage at the Port of Barcelona. But when I got there, I was hanging out with the participants and they were ordinary people from all over the world, students from Malaysia and physicians from Australia and retirees from Menorca. And I just thought, “Wow, these people have such moral clarity and political conviction and personal courage in joining this mission and assuming these risks.” And really, being able-bodied and romantically single and professionally committed to these principles of international solidarity, I felt like it was this sort of special responsibility or obligation that I had. So I was very inspired by a lot of these people to actually take part in the mission and boarded in Tunisia as a result of long reflections on what it means to take seriously the moral clarion call that is the genocide in Gaza.

There were three very different things that we were doing on a daily basis. The first one was just nautical life, like cleaning toilets, cooking breakfasts, being on a boat. That was a major challenge for someone like myself, who is very used to sitting on a computer for 12 hours a day. The second challenge we had was just coordinating the actual Flotilla itself. Many of the readers of this interview will be familiar with the multiple waves of drone attacks that we suffered when we were at sea, which weren’t just a risk to our lives and to our boats, but also to the vectors of bureaucratic sabotage for the mission itself. So in Tunisia, we were drone struck, and it’s confirmed that Benjamin Netanyahu approved this drone strike in the port of Sidi Bou Said. And this was dangerous for the people on the boats and the mission itself. But it was also really dangerous because it was an attack on the sovereign nation of Tunisia. And in that sense of it being basically a declaration of conflict against the government of Tunisia that had given us safe harbor, it really became a way for the Tunisian police to open an investigation, to search all the boats, to really slow us down and risk the whole mission kind of coming apart.

So that was the second major challenge: how do we complete this mission in the face of so many challenges, in the face of boats breaking, masts being exploded, police chasing us down? And that was related to the third major task that I had in particular, which was how to coordinate the politics. We had people from 45 different countries, 45 different national delegations, but that didn’t mean necessarily that all those countries were being activated, that their parliamentarians understood that they could use this opportunity to pass legislation, that their presidencies understood their responsibility vis-a-vis their citizens on board, that their social movements were switched on in terms of coordinating land-based mobilizations with our sea-based mobilization. There was a big political challenge that was really exciting and very, very fascinating, but also very logistically challenging. How we could make the most of this slow-traveling convoy at sea to try to activate and facilitate an even stronger solidarity move with Palestine and the respective countries that were taking part in the Flotilla? And that is not over. We did our best to try to bring the world’s attention once again to the humanitarian crisis in Gaza and to the rogue actions of the State of Israel, but I think that that was just one more step in a broader journey, I think.

MOSKOWITZ: What did you eat for breakfast?

ADLER: I don’t eat breakfast usually. [Laughs] And this was of a piece with a broader dietary process in the boats, which was how could we get our stomachs smaller over time and prepare for a potential hunger strike in case of abduction at sea. So the meals were unglamorous—a lot of canned chickpeas, canned green beans, a lot of rice and whatever vegetables we could source from land. But in general, we were trying to get down from a three-meal-a-day structure to a two-meal-a-day structure to a one-meal-a-day structure to see if we could be a bit more prepared.

I don’t want to normalize or explain away the shocking aspect of our abduction at sea. Like we should, by any interpretation of international law, have been able to reach Gaza. I think we were not naïve; we were clear-minded about our prospects of doing so. And in that case we wanted to be as prepared as possible in terms of running drills every day to practice our nonviolent and pacifist methodology in case of interception, as well as preparing our bodies for what might be coming our way on the other side of that journey.

MOSKOWITZ: I mean, that takes an incredible amount of discipline, and also emotional discipline. How do you get through the day knowing that this might be on the horizon?

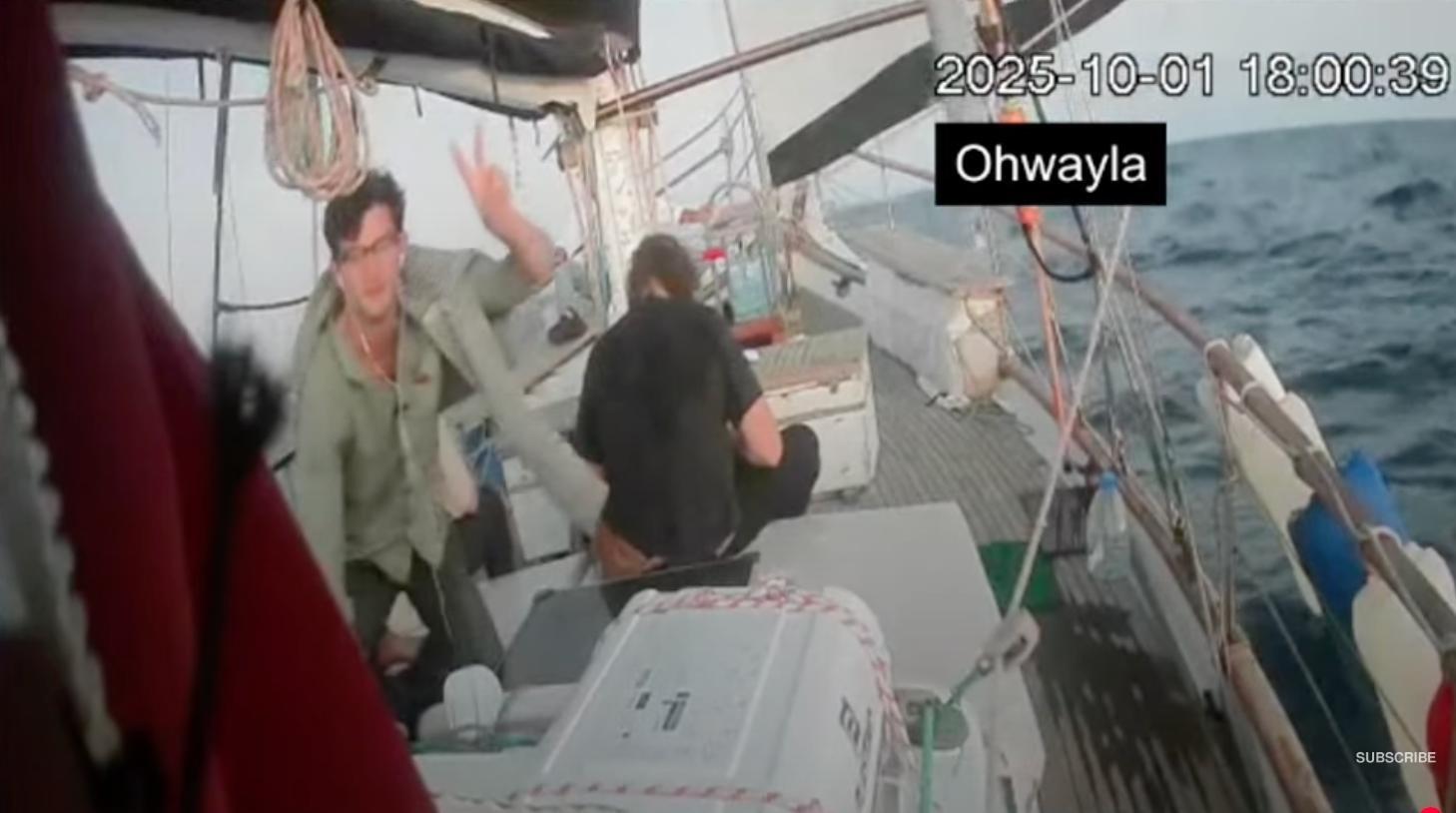

ADLER: Well, first of all, after my first boat broke down, I was moved to the OHWAYLA boat, which was full of U.S. veterans. And if I thought I knew discipline, these veterans really taught me a new degree of discipline. I think a second aspect of it, Paris, was that the journey was really, really long. I mean, we’d been at sea already for a month. So it felt like, even if we’re approaching the so-called red zone, and that’s scary in one sense for people who are watching at home, for us we can’t believe that we actually succeeded against all odds, drone strikes and bureaucratic war sabotage and all logistical challenges of being on these boats.

And then I think the third was that once we were able really to marshal so much of the world’s attention to the mission, there was a sense that it was now no longer a question about us as individuals or our anxieties, our fears, our projections of possibilities of what might happen to us. We were all there as representatives of something much bigger than ourselves. I do think it’s tempting to read the story of the Flotilla backwards and say, “Oh, well, these were always activists who were always going to be protected, and the State of Israel was never going to do anything to them,” but that’s just not true. I mean, we had to work hard at sea to build certain diplomatic protections for the Flotilla as we sailed along. After the first drone strike, it became clear that we were really on our own.

And once the State of Israel, through its foreign ministry and through mouthpieces like Ben-Gvir, were calling us terrorists, saying this was the “Hamas Flotilla,” it became clear that there was a real and present risk to our lives on the boats, and in particular to the people who were coming from geographies that were perceived as particularly threatening to the State of Israel. So it’s one thing to be Canadian or Australian, but it’s another thing to be Tunisian and Algerian. So part of the work was trying to slowly gain or achieve a degree of protection for the Flotilla. So first, that came in the form of 16 states calling this Flotilla a humanitarian mission and saying, rhetorically, that there will be accountability for whatever violations of international law may be committed against the Flotilla. That was a huge achievement, and then, of course, on the basis of the social mobilizations happening on the ground in Italy, the Italian government said they were going to send this frigate to protect the lives of our citizens. Each of those were fruits of the social mobilization that was happening across the world. And each of those played a role in us feeling a bit more protection in the end when we were trying to break the siege and reach the shores of Gaza. But ultimately it was an oath that we made to ourselves, to each other, and to the people of Palestine that we would just sail and sail—as was our right—until we could no longer sail.

MOSKOWITZ: I know you’ve already talked about this a lot in other places, but for people who don’t know, can you just briefly explain what happened and how you ended up in an Israeli prison?

ADLER: So this convoy presented a real problem for the Israeli Navy. It wasn’t just one single ship they were trying to intercept. We were 40-plus boats with 450 people sailing through the middle of the night. And at some point, it was 2:00 o’clock in the morning, 3:00 in o’clock in the morning, I thought maybe we’re going to actually reach the shores of Gaza. Maybe it’s possible. And there was a giant barge in the middle of the sea, a giant Israeli naval barge that was chasing us down and trying to smash our boats in half. We would sail away from them in a kind of lethal game of cat and mouse I should say, and we would just continue on and keep sailing. And the Israeli Navy would come and say, “We’re Israeli Navy, turn off your boats. You’re entering a war zone, you can’t sail here.” And as per our oath, we just continued sailing because they have no legal rights to stop us or seize our boats or abduct us in international waters where we were.

At a certain point, however, I looked down and saw sniper lasers all over my chest and thought, “Okay, maybe this is the end of the line.” At which point, smaller naval ships with their lights off, very menacing, approached the boat. It was scary because every time they would approach, the signal would get jammed, and part of what we were trying to do with the Flotilla, by arming it and outfitting it with these CCTVs as well as using our own phones, was to make visible this illegal process. But every time we would approach, the CCTV would go offline and our phones wouldn’t work.

This is of a piece, I think, with what we were talking about before—law enforcement wearing masks and turning away from the camera or using drones, stripping away accountability. These are all ways in which law enforcement or naval forces or army forces or police forces would much prefer to do their jobs under the cover of darkness. So the boats were boarded, we were sort of very violently searched and then effectively kidnapped. We were thrown into the basement of the boat. Israel took the boat. These young naval officers just occupied the boat and stole the boat from us and drove us to the port of Ashdod several hours away, where the process of detention, abuse, and disappearance began. And of course, the State of Israel was putting out no information because they wanted to protect their right for things to have gone wrong by accident, for there to have been casualties or fatalities that were the product of like, oopsie daisy, we killed some people. And that’s why the State of Israel has been so effective, especially in the U.S. American press, using the gullible nature of our mainstream outlets. And then, at best, we get both sides and say, “Activists allege this, the State of Israel contradicts it.” Or we just get the straight up Israeli account of what happens and the truth is always hidden behind in the fourth paragraph of some coverage of an Israeli war crime.

MOSKOWITZ: Given that you were abducted and that Israel stole your boats and that the press wrote of this in this way that kind of underplayed it, do you feel like it was an effective action?

ADLER: I won’t lie to you. When we got out of the internment camp and were dropped in Jordan and I had access to somebody else’s phone for the first time, I Googled “Flotilla NYT.” I wanted to know if our most prestigious media outlet, the Grey Lady, the paper of record, had asked questions about where we went? What happened in the course of the largest abduction of U.S. citizens in the 21st century by an ally, let alone an adversary? Did they ask where we were taken? And the answer was no. They did not ask. Most press outlets, most journalists as well as most politicians, basically stopped paying attention the night of the interception and thought, “Oh, the little game of cat and mouse is over.”

When we were in prison, I will admit, rather foolishly or naively, that I was having fever dreams of some courageous or even opportunistic Democratic senator getting on a plane and saying, “I demand to see the U.S. delegation. Show me where they are.” There was nothing, none of those responses, none of that healthy reaction that would’ve happened in a more democratic society capable of mounting any kind of critical response to the State of Israel.

And what that ultimately taught me was that the success of the action did not only hinge on what happened the night of October 1st, of Yom Kippur, when we were intercepted. The success of that action also hinges on each of us as delegates and representatives of that Flotilla going out into the world and becoming effective ambassadors. So I think that the conversation we’re having now is part of the answer to your question of whether we were effective. It’s going to hinge on whether or not we can turn that experience into a further vehicle for raising consciousness, motivating mobilization, and encouraging people to take more seriously their own moral kind of responsibilities to get involved and to do something to stop this genocide, but also to defend international law and democratic institutions.

MOSKOWITZ: I think that gets to this thing I’ve been struggling with a lot now, which is that even for people who do care, the kind of inputs and outputs are no longer the same. There used to be this idea in America that if these horrible things were happening, you went on the street, you protested, and eventually that changed things. People listened, politicians listened, and there was a semblance of democracy, even if it was never fully so. And now people are being disappeared off the streets, governments are breaking international law to do whatever they want. And then it’s like, how does one respond to that if the rules are no longer the same?

ADLER: Yeah. I think we need to be more curious about the rest of the world and how they have managed to do this. I mean, in Italy, for example, you have a fascist government in close alliance not only with the State of Israel, but also with the United States of America. Why was Italy the most vociferous in its advocacy for its citizens stuck in Ktzi’ot prison? Why were they the most proactive in providing a frigate for our safety and defense? Because the trade unions of Italy in ports like Geneva and Naples and elsewhere basically said, “We will shut down this country, we will block everything if the government does not respond to these demands.” So they did.

And in this country, one of the things we’ve lost sight of is the ways in which we as citizens sustain or maintain or retain some control vis-a-vis our representatives? How do we move away from just an Instagram post or a letter writing campaign to actually exercise some control? And that ultimately, I think, does run through our trade unions withholding labor in ways that are actually really scary and menacing to our leaders. And that’s a bridge that we just have not crossed. Recently, the Longshoremen Unions had the largest strike in decades where they basically refused to load goods. But what was the one carve-out they made on the basis of their allegiance to the U.S. imperial project? They would still load weapons and still load weapons to Israel, even if they were on a big strike.

So we have a double problem here. First, we have the problem of how do we rebuild a sense of confidence and a material focus in the ways in which we choose to react to or demand accountability for the actions of our government? And secondarily, how do we focus that new trade union militancy on the issues of foreign policy that matter so much to the shape of the world, as opposed to just exclusively on questions of rights and services and provisions and conditions of our working class here at home?

There are ultimately no shortcuts, and that’s the bad news. We do have to do the work of rebuilding a lot of these social institutions that have crumbled over the past half-century. But there’s a lot of promise there as well that, if we do that work in the face of this galloping fascism, we can actually fight back in ways that feel more substantial than going down to the No Kings protests for a half-hour and going to brunch after.

MOSKOWITZ: I know it’s a leading question, but do you have hope that people will understand that they need to start looking to their fellow men and organizing and doing things differently than we’re accustomed to? I feel like there’s this opportunity to reformulate how we do things, and maybe that’s the kind of silver lining: everything is kind of fucked and nothing is working as it used to, so why not reorient how we think of our lives and the world and activism and each other?

ADLER: At the same time, I don’t think it’s rocket scientific, and I wouldn’t want us to think that it all has to be remade from scratch. We’re living through a very classic formula for the development and deployment of fascist politics. It can feel spectacular at times, but it’s really pretty classic. So I have hope in a morbid sense that eventually the swathe of U.S. Americans that are considered to be the wrong kind, considered to be undesirable, considered to be unprotected or stripped of their basic civil rights, could create a more significant backlash. The question, Paris, is whether it’ll be too late by the time that that happens? How can we get our fellow countrymen and countrywomen to get ahead of this curve to catch up to where fascist politics is happening, to take seriously the prospect that drones for police forces may be coming to our cities, which would present not only a lethal threat to our lives, but an existential threat to mechanisms of accountability for law enforcement in our communities? That’s not the right line to end on, but you hear what I’m saying?

MOSKOWITZ: Yes, yes. Well, thank you so much for taking the time. And thank you for all your work.

ADLER: Of course. You too.