To the Hills

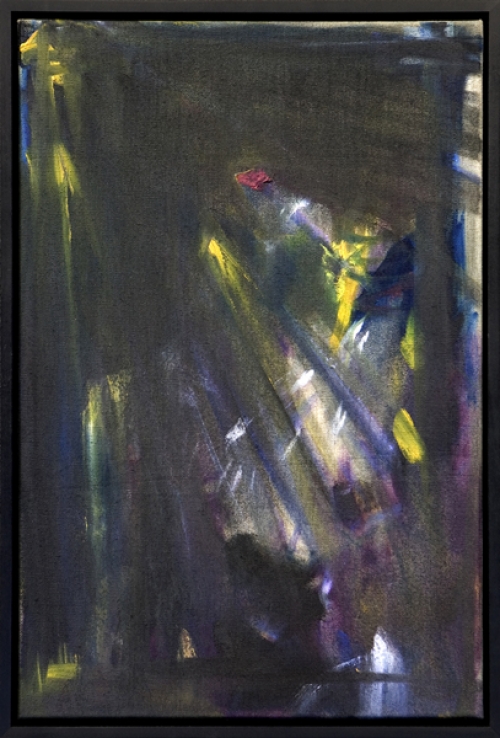

Installation view of “The Devil,” 2009. Courtesy September Gallery, Berlin

Not for over a century have painters headed for the hills to paint abstract landscapes and religious icons. But that’s exactly what Berlin-based artist Carsten Fock has been doing recently, to remarkably contemporary ends. While other artists in a similar situation might appeal to our escapist impulses in a time of crisis, Fock’s relationship to painting is grounded in a complicated exchange of dissent and fondness for the medium and its history. Previously, Fock covered entire canvases in all-black felt-pen hatch patterns as a rejection of painting in the spirit of Ad Reinhardt’s monochrome “Last Paintings.” However, instead of Reinhardt’s attempt to lead the viewer to a visual neutral point, Fock’s monochromatic works are an accumulation of varied detail in the rhythm of their hatch lines, and therefore suggest an almost painterly effect. Later, Fock, who grew up in Soviet East Germany, began working with collage and images from Western culture like the Chanel logo, American soldiers, or the red, white and blue itself, covering them with a simple coat of acrylic, thereby treating painting for its superficial function. And now, Fock is dissolving much of his noncompliance with dowdy art practices in his solo show, “The Devil,” at Berlin’s September Gallery, where he presents a series of explosive new works—many of them paintings – of abstract, demonic landscapes and frenzied, expressionistic religious icons, echoing more maniac than minimalist, more Outsider provocation than insider strategy. But don’t start imagining Fock as some anachronistic romantic, for he also reveals that behind even the purest artistic intentions is a taste of Pop.

ME: We were just looking at your monochromatic felt-pen drawings of hatch patterns, which were some your first works, correct?

CF: Yes. I did them originally for my solo show at Jan Winkelmann Gallery called “Black.”

ME: And they were made as a reaction against painting?

UNTITLED (LAST DRAWING), 2007. COURTESY JAN WINKELMANN GALLERY

CF: Yes. I stopped painting for a while just after I began studying with Per Kirkeby, and started working with felt-pen instead.

ME: Why did you make that transition?

CF: Well, the history of painting is something really heavy, and in the ’90s it was shocking for a lot of people. Everyone was doing much more conceptual work. So then I realized that it might not necessarily be contemporary.

ME: Painting?

CF: Yes, so I started working with felt-pen. But again, this wasn’t new. Andy Warhol, and even Kirkeby, did a lot with felt-pen. It’s fast.

ME: It’s also heavy as a material. It reminds me of Ad Reinhardt’s “Ultimate Paintings”- his statement, “Painting is black.” They have the same massive monochromatic weight, and, of course, you both work in black.

CF: Absolutely. I found Reinhardt’s painting so radical that it just made me stop painting—especially his works from the last ten years of his life, which were almost all the same size and only done in black. But before that he did illustrations and drawings.

ME: He was a very diverse artist, and even dabbled in publishing, for Glamour and The New York Times. He also did some design for the Brooklyn Dodgers. So how did Kirkeby influence your work? Because just as much as your “Black” series seemed influenced by Reinhardt, your other drawings seem prompted by Kirkeby in their more figurative—instead of abstract – elements. And you’re painting again!

CF: Well, I’ve been coming back to my roots in recent work. It’s not just Kirkeby that’s in this work, but also post-war American painting: Philip Guston, for example, who was working more abstractly before he started using his comic style. And now I’m more interested in having a more emotional process – having the strokes, but also having the break in the strokes—and not simply the direct, mechanical technique of my previous work.

Untitled drawings, 2008; 2009. Courtesy of September Gallery.

ME: And similar to Guston, there’s tension in your work between figuration and abstraction. Even the images you’ve used from commercial and political culture—like the Chanel logo or the American flag—are distorted and they’re significance covered up. How has your work developed through the use of these signs and the deflection, and even renunciation, of them?

CF: It’s a kind of working process, which has never been easy to explain.

ME: Would you consider it simply an exercise in form, or does it have deeper significance?

CF: Well, when I was doing a lot of collage I had a newfound freedom because I grew up in East Germany, and escaped in 1988 a year before the Wall came down. Because I didn’t have a personal history with Western signs, but instead was restricted from them, it seemed appropriate to start using them when I began incorporating figures into my work. Before it was difficult for me to use figures because that’s all art was comprised of in East Germany.

ME: But in addition to collage, and using signifiers of Western capitalism, there are a lot of Abstract Expressionist influences, which was a movement certainly not happening in the GDR.

CF: East German art was entirely for the political system. So breaking out of that is an important part of my history.

ME: Now it seems like your work is more mystical and heavily influenced by Outsider Art – especially the newfound Christian iconography, which wasn’t present before.

CF: This is new. Two years ago, I had an exhibition in Andratx, Mallorca, where I was surrounded by amazing landscapes, and I was isolated. It was a liberating experience to leave the political discourse and come to something more essential. I went back again last year for a longer period and only brought a couple books with me. One on Ad Reinhardt and the other on the symbolist Gustav Moreau. And a book on Otto Dix as well, whose late work includes a lot of Christian iconography.

ME: So now are you making most of your work in the countryside?

CF: Yes. All these works started in Majorca, and continued while I was in the north of Germany living in a really isolated castle. I just spent the winter in Vienna, which feels almost like a small island for me; the same special energy. And a lot of the way this show at September is curated is influenced by small churches on Greek islands. But I’m not interested in building a church.

MVE: You’re not building a religious practice. It’s completely aesthetic for you—and much of Outsider Art is spiritual, but has become aestheticized for a market. Is there any particular Outsider artist that’s informed your work?

CF: At a time I was really interested in Adolf Wölfli, who made these really obsessive, dense drawings filled with all different types of images from religion, sexuality, and pop culture. He did a Campbell’s soup piece in the early twentieth century, well before Warhol.

MVE: I didn’t know that. And in terms of your involvement with other, more commercial, endeavors, you’ve collaborated, respectively, with Berhnard Willhelm on a collection, and DJ Fetisch on record designs.

CF: I started with Bernhard in 2005. He asked me to do a whole women’s collection with him. And for me it was great, because it was a break from all of my abstract, felt-pen work. I did the graphics, and then the fabric, and we worked together on the whole concept. But it wasn’t gimmicky like it sometimes is today, like fashion colliding with art. It was just two people collaborating. But with Bernhard it was really special.

ME: Well, his work is also on the periphery of fashion. He’s more alternative.

CF: I think he’s much more of an artist than a fashion designer. I saw his show recently in Antwerp, and we created some of the sets together. For me, he has so much fantasy, and he’s really free of clichés. And also with Fetisch, we had a creative synergy and really learned a lot from each other. And that’s what a collaboration should be. I’m really influenced by these friends of mine, even though we may not work in the same field. I’m very interested in collaboration because it’s much more than just me. With my own work, I’m very much by myself. For instance, in Vienna, I was in my studio for more than twelve hours a day, alone. And if I do some form of collaboration, I’ll go to Paris and work together with someone, eat together, and talk together.

ME: So is painting private?

CF: Yes, but on the other hand, it’s so connected to its own heavy history, which makes it go beyond the process itself. But I can’t let it go.

Carsten Fock, “The Devil” is on view through June 13. September Gallery is located at Charlottenstrasse 1, Berlin.