Artist Rachel Harrison and Actor Matt Dillon Confront Their Own Worst Critics

Jacket by Gucci. Sweatshirt by Supreme. Shoes by Camper. Pants Rachel’s Own.

The best artists don’t simply improve art or beautify it or break down a few of its boundaries. The best ones change the very definition of what art can be. Rachel Harrison is one such artist. A confrontation with one of her sculptures simultaneously draws upon the entire history of Western sculpture—from classic Greek statuary to the Duchampian ready-made—and blows all of those distinctions and separations to dust. In her capable hands, any object, from an upturned bucket to a fur pelt to a wall-mounted telephone to a picture of Leonardo DiCaprio, when fused with her often brightly painted, inchoate polystyrene forms, can take on a sublime visual poetry—not to mention plenty of biting wit, red-faced humor, sly anti-monumentality, and the unshakeable dread of teetering on the brink of disaster.

Harrison seems to take particular pleasure in grabbing hold of the swirling, chaotic detritus of our inane, over consuming, pop-and-political culture to improvise new meanings and unlikely connections. She has been hard at work on this project since the early 1990s, and it isn’t just sculpture that she’s revolutionized. She has tackled photography (including her “Perth Amboy” series from 2001, which takes as its subject the purported apparition of the Virgin Mary on a suburban window in a small New Jersey town) and drawing (among her most memorable is her 2011 and 2012 series dedicated to the late singer Amy Winehouse). This month, Harrison is finally getting a retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art—and, in a sense, Rachel Harrison Life Hack is less a staid representation of her masterpieces and more an audacious, rambunctious artwork all in itself. This past August, on a gruelingly hot New York afternoon, the actor and artist Matt Dillon stopped by Harrison’s Brooklyn studio to talk about making art, the fear of mass shootings, and living in a very crowded universe.

_ _ _

MATT DILLON: Do you work at night?

RACHEL HARRISON: Not as much I used to. Do you?

DILLON: Yeah, sometimes we do night shoots. Some actors, when they get older, won’t work at night. They get to a point before they sign on where they ask, “Are there any night shoots?”

HARRISON: But sometimes it’s better to have the world turn off. Many artists work at night. Six o’clock is a good hour because everyone stops sending you emails. The world’s not going to bother you, and if anyone does, it’s probably a friend to get a drink.

DILLON: Philip Guston was a night painter, wasn’t he? I always felt like there was something mysterious and poetic about working at night.

HARRISON: And the night is good for peace and quiet, although I suppose you can always just turn off your phone. [The artist] Charlie Rayonce told me he gets up early in the morning to take walks in nature. There’s an owl he sees regularly. He has said this is the time he can think. I myself am not a morning person. But one of the reasons to have a studio in the first place is that you can keep the world out and control your thoughts.

DILLON: Our thoughts are really the only things we have dominion over, more so than our feelings.

HARRISON: I thought actors could control their feelings. Like, you can make yourself cry or seem angry on cue. I thought you were trained in that kind of control.

DILLON: We definitely are. At a very young age, I became comfortable with my extreme emotions in a way that other people might not be. We’re encouraged and conditioned to do that. A lot of directors think acting is a kind of alchemy, but it’s really a craft. [Lars] von Trier got that. For that last film we did [The House That Jack Built], Lars would give very simple direction, which is music to my ears. We never rehearsed, so we were encouraged to take risks. As an artist, that’s something you must undertake all the time. Actually, I should say that we aren’t encouraged to fail so much as we’re encouraged to take chances with the risk of failing. In the end, you can always do another take. There’s always another day.

HARRISON: Or, in my case, another piece. I’ve had conversations with artist friends about how it’s all about failure. Because you never really get what you want. If you did, you wouldn’t make another work of art. So every work is just there to help you make the next one. It propels you forward.

DILLON: So you don’t ever feel satisfied with your work?

HARRISON: Sometimes I do, much later. Maybe a year or so later. In the moment, I’m like, “Okay, it’s done. I can’t do anything else with it.”

DILLON: Today I was listening to this Charles Mingus record called Tijuana Moods. And right on the cover, he says, “This is my greatest record.” I’ve noticed that attitude with musicians in particular. They feel like the last thing they did was their greatest thing.

HARRISON: Do you think people are being honest when they say that? Or is it bravado?

DILLON: I think he really believed it. But in general, we’re not necessarily the best people to judge our own work, right?

HARRISON: That’s the thing. How does anyone know? It’s a crap shoot. And with art, it’s about the long run. Sometimes I look at my work and think, “Maybe it will look better later.” When I first started showing in New York, most people didn’t know what to make of my work. And that was fine by me.

DILLON: You were a little ahead there.

HARRISON: Or behind. Or out to lunch. Or failing in public. Or whatever it is.

DILLON: It’s also nice to hear someone say, “My best work is ahead of me.” I’d like to believe that. Now you have this retrospective at the Whitney that represents 25 years of your work. I’ve been in situations where people have asked to do a life tribute of my work, and I’m like, “Well, I feel like I’ve got a lot of life left and a lot of work left.” You do, too.

HARRISON: We’re the same age, but you started when you were really young. So you’ve got 40 years of work already.

DILLON: I hate the idea of a lifetime achievement award. If they could just take out the “lifetime” part. What comes first for you: the material you are working with or the idea of the piece?

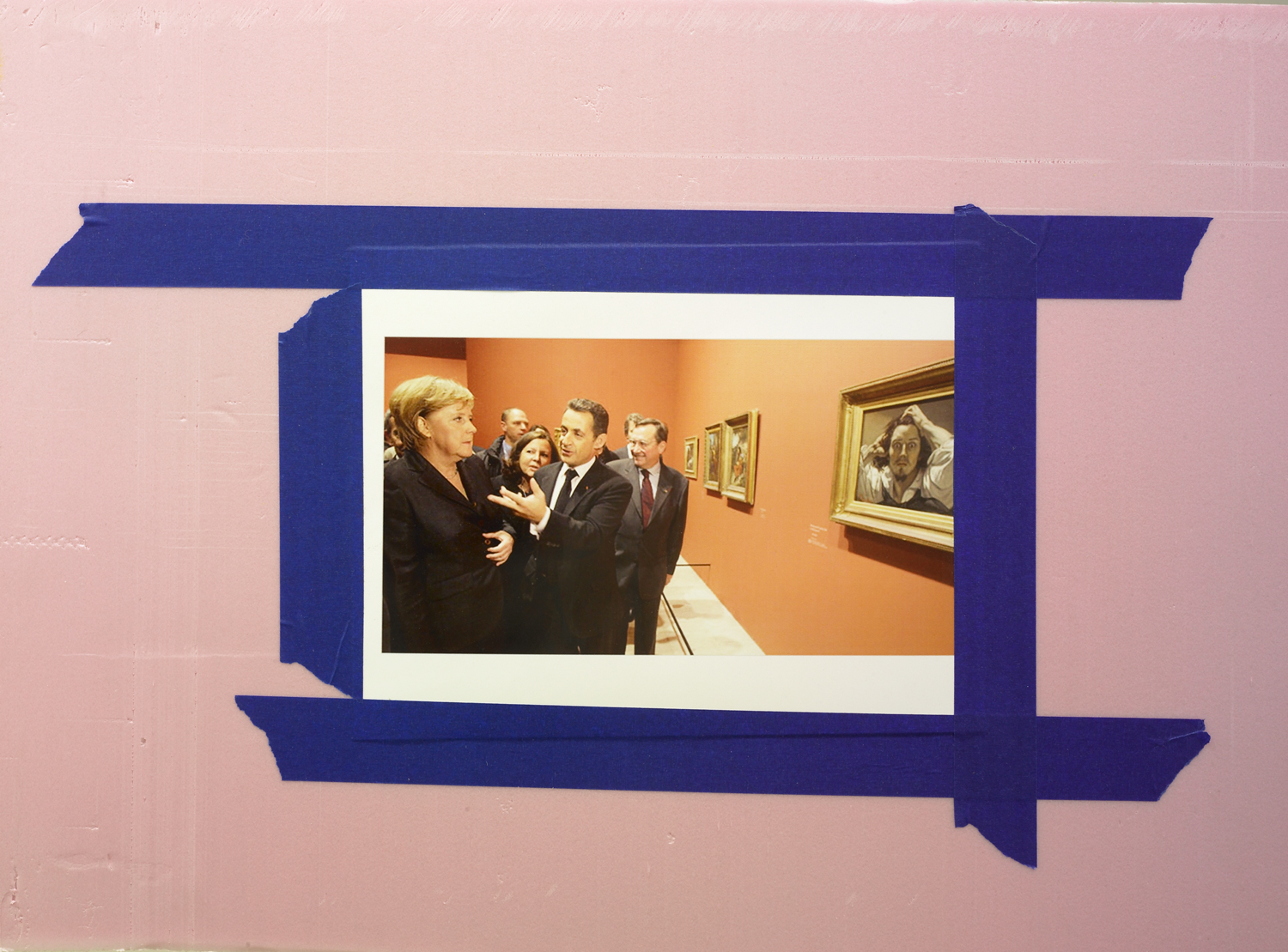

Image courtesy of artist and Greene Naftali, New York.

HARRISON: I always want to be in the middle, which is a really hard place to be. That’s why I leave so much crap around and nothing here is finished. It’s better to just throw the dice and see where you land and then respond to it. That’s why I couldn’t be a painter, because a painter has a blank canvas, and that would just be too terrifying. In terms of material, I combine and layer things to make sure I’m inconsistent. I’ve gotten it down to a certain way of making forms, but then I’m going to be constantly responding to what I’m working on. I really don’t know what I want it to be when I start. But you make art, too, right?

DILLON: I draw, paint, and do collage.

HARRISON: And your dad was an artist.

DILLON: I come from a family of artists. They’re more like academy artists, the traditional American school. My uncle was a creator of the Flash Gordon comic strip and he and his brother did Blondie. So they came from the school of comic book artists. My grandmother was a phenomenal painter of a very traditional style.

HARRISON: I can’t believe your uncle invented Flash Gordon.

DILLON: Yeah, I think he was rejected on Flash Gordon three times before it was accepted.

HARRISON: I get rejected all the time—it’s very common.

DILLON: No matter what, we’re always dealing with some form of rejection. That’s a given.

HARRISON: But sometimes the feedback isn’t productive. That’s another question you have to face in making art. Once you start showing, do you listen to the critics? I mean, do you read your film reviews?

DILLON: I don’t read them. Well, that’s not entirely true. I wrote and directed a film that came out in 2002 [City of Ghosts]. We filmed it in Cambodia and it was very difficult but very rewarding. It was the movie I wanted to make and so I could handle any rejection or criticism of the film because it was mine. I can own that. As an actor, on the other hand, I’m playing a part in a larger film. And it isn’t mine.

HARRISON: So you can step back from it.

DILLON: Of course, there have been critics whose work I admire and listen to. In my industry, unlike in the art world, there tend to be some basic judgments that everyone makes when they see a movie, and I’m not sure this is what happens when people walk into a gallery or a museum.When people see films, they decide,“I liked it, I loved it, or I hated it.” The reaction is very primary. I suppose people do walk into galleries and say, “What is this? My kid could have done that.”

HARRISON: If you’re an artist, you accept the fact that people are going to have opinions about things they don’t know anything about. All art isn’t for everybody. A general response to art is often demeaning, and maybe it’s because there is an expectation of what art is supposed to do. How can it live up to that expectation? If I gave a shit about what anyone else thinks, I wouldn’t bother, because that would be me looking for an external reward.

DILLON: That’s how I feel about the films I’ve made.

HARRISON: Actors choose their parts. Some have no choice because they have to take any work. You seem pretty selective.

DILLON: I make a decision about who I want to work with and I know I’m going to come away with something rewarding in the process. Often, the subject of the film is less interesting to me than the people I’m working with. In the case of that last Lars movie, I know there are a lot of people in the world who are fascinated with serial killers. I’m not one of them.

HARRISON: What about Charles Manson?

DILLON: Before I made that film, I said, “Let me do a little research.” When I looked online, I was like, “Jesus, the internet is all about serial killers!”

HARRISON: Let’s talk about domestic terrorism—not serial killers but what’s going on in America with young white guys with guns going into public places and shooting people. It’s terrifying.

DILLON: There has to be something done about it. So many people get wrapped up in this idea that the Second Amendment is some kind of holy thing that can never be changed when the whole idea of an amendment is that it’s meant to be changed. That’s what the word means: to amend, to change.

HARRISON: And if you think about laws that were written more than 200 years ago…

DILLON: Exactly. We don’t need to be walking around carrying muskets anymore. And these guns that are being used now are not being used for hunting.

HARRISON: No one needs an AK-47.

DILLON: We’re on the same page. It’s just terrible.

HARRISON: We do come from a somewhat similar background. You’re from New Rochelle. I’m from Hastings.

DILLON: I was born in New Rochelle,but I grew up in Mamaroneck.

HARRISON: Near New York. How much do you want to script what the public knows about you?

DILLON: I’ve never consciously tried to construct an image of myself.

HARRISON: I think even we non-actors, or at least we artists, have to sometimes play a role or present ourselves a certain way.

DILLON: But it can be very upfront. I’m an artist and that’s part of my thing, right? It’s not a con job to be an artist. It’s what you do.

HARRISON: But it could be a transparent persona.

DILLON: It’s the same thing as an actor. I’m playing a character in films, but I’m not showing up and pretending to be somebody I’m not. That gets into an area of darkness, this kind of con artistry thing. It’s like putting on a mask.

HARRISON: I guess I’m thinking about whether or not [Andy] Warhol was playing a role. Or Salvador Dalí with the mustache. People think that they created a persona as part of their work. But with an actor, you can not take yourself out of your performance.

DILLON: You also can’t take things personally, you know?

HARRISON: Yeah. Artists can take things really personally when they hear criticism of their work.

DILLON: But you’re right, when it’s your actual self up there, it can be hard to detach from it. If your choices are emotional and personal, like the way I trained as an actor to work from the inside out, it’s always coming from a place that’s real. But I know I’m playing a character. People always say, “It must have been really hard. Did you take it home with you?” Yeah, I took it home with me sometimes. But it’s not like I go into some psychosis and become the character.

HARRISON: You’ve been an actor your entire adult life. Do you ever get into a situation where you feel like you don’t know how to do it? One of the things about being an artist is that I have days where I have no fucking clue what I’m doing and I feel so lost. Then I talk to other friends who are artists about this, and I realize it’s not that uncommon to be filled with doubt. But I really can go days where I feel like I’ve never made a work of art in my life. It’s a terrifying place to be.

“Mustard and Ketchup,” 2008 (detail). Photo: A. Mori. Image courtesy of the artist and Greene Naftali, New York

DILLON: It’s terrifying, but you’re ultimately the final decision on what that is. You’re the one who’s going to decide in the end what it’s going be. Unless you step aside and let someone else dictate what the finished artwork is.

HARRISON: Some artists do that as apart of their process. They let other people in.

DILLON: Didn’t [Martin] Kippenberger do that? You’ve used him in your work. And Dick Cheney. And Amy Winehouse. None of them are easy targets. Well, maybe Dick Cheney is an easy target.

HARRISON: Well, they’re available. Kippenberger is such an important artist in my opinion. One thing about making art is engaging in a certain amount of negativity. You can’t help it, you’re thinking critically. I feel like Kippenberger could really make something dark into something comedic.

DILLON: Like in his self-portraits, he really lets it all hang out. Literally. A lot of those paintings are… I don’t want to say exuberant. That’s not the right word.

HARRISON: Maybe that’s what’s good about Kippenberger. It’s hard to describe or get right at that emotional outlet.

DILLON: But you are free like Kippenberger was. You work in a lot of different mediums just like he did.

HARRISON: I’m restless.

DILLON: Does one medium inform the other for you?

HARRISON: Oh, absolutely, because ultimately it’s all about space. I think a lot of photographers work in the medium of photography because you can transform something 3D into something flat. In the most elemental way, you turn the world into apiece of paper. With sculpture, you’re dealing with the world directly, in space. The new drawings I’m working on, I want those to be about space via photography and sculpture. I’m drawing on my photographs of drawings of sculptures. There was a time in my life when I couldn’t work on sculptures at all. I’d just hit a brick wall. That’s when I started the Amy Winehouse drawings. You play guitar your whole life and then you’re like, “This isn’t working anymore. I’m going to play the trumpet.”

DILLON: And I imagine that it challenges you when you go back. Like, if you’re doing photography and then you go back to drawing or doing sculpture.

HARRISON: It becomes more difficult.

DILLON: But because of that, it probably strengthens the work.

HARRISON: Or it makes you feel like you know even less. When I was in college, I decided I should start making sculpture because it was physical. Drawing and painting, you had to sit still. In sculpture, you’re running around, you’re getting up, you’re using tools, you’re going to lumberyard. Then I decided to make a project that was a rocking chair, and I had to bend a piece of wood. I made this whole elaborate contraption to steam the wood first in a long PVC pipe.

DILLON: Funny, you don’t have many chairs in your studio.

HARRISON: No, because then there’d be people.

DILLON: But you’ve got a lot of tables.

HARRISON: I work alone and I like to spread out. I put my sculptures on wheels so I can move them around and paint on them. That’s why some sculptures have wheels. I get used to them at that height.

DILLON: How did you first get interested in art?

HARRISON: I was at a liberal arts college, procrastinating in the college library. I picked up a book and read about Chris Burden getting shot, and it hit me. I was like, “Wow, an artwork can be immediate and powerful, like a bullet.” He also lived in a locker, was crucified, and laid under a tarp on the L.A. freeway. He was literally putting his life on the line. There’s also humor in his work, and this made it feel all the more complicated.

DILLON: I have to ask: Do you see yourself as a woman artist? I’m going to guess that your answer is no.

HARRISON: I’m not answering that. As an artist, I just want to make art.

DILLON: And what do you want your art to be?

HARRISON: I think good art, really great art, can be anything and can break all the rules.

This article appears in the fall 2019 50th anniversary issue of Interview magazine. Subscribe here.

———

Fashion Assistant: Gregory Miller.