CLICK

“Complete Fucking Alchemy”: How Luisa Opalesky Captures New York City Grit

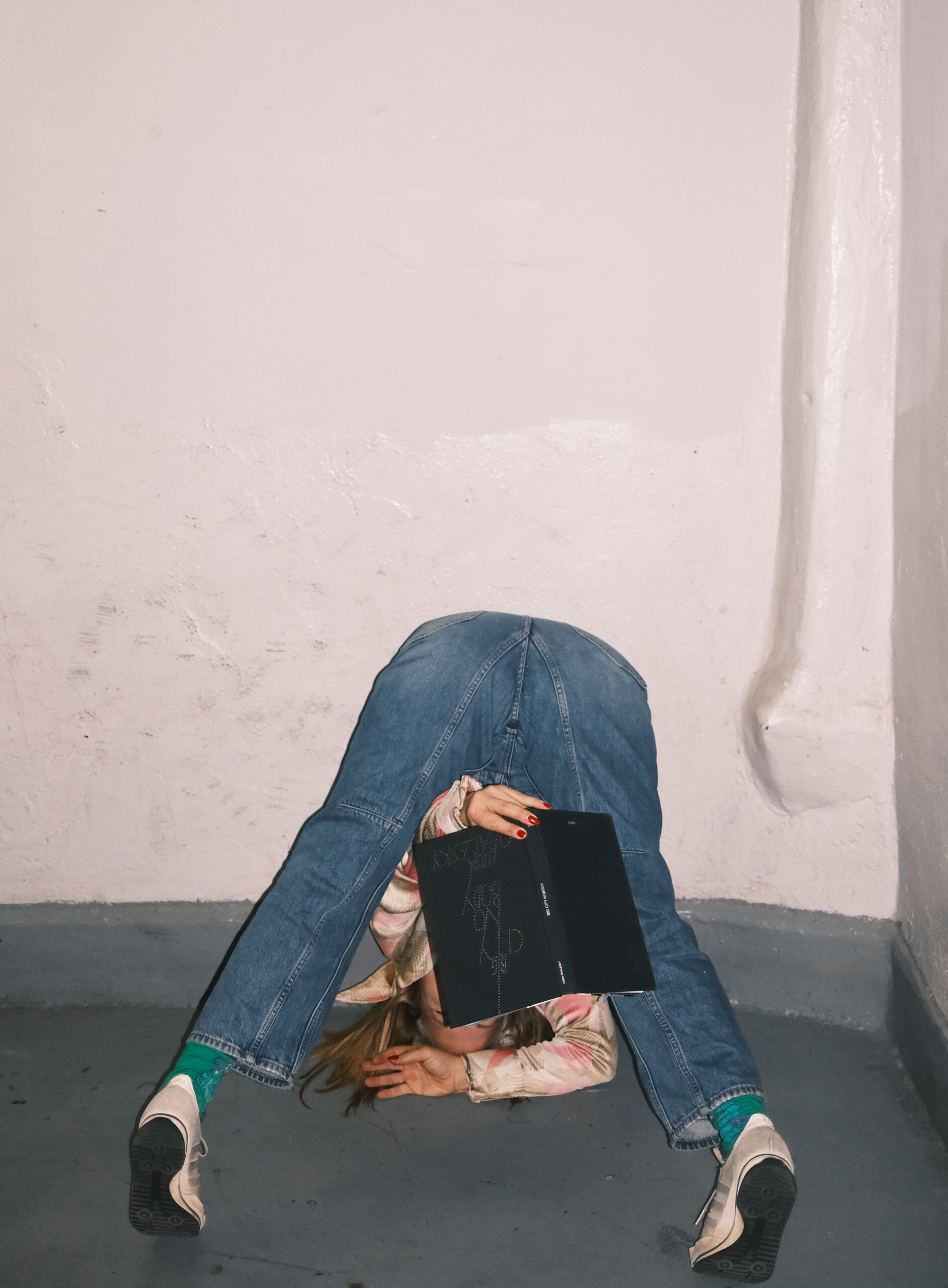

Whether it’s crawling on sidewalks or hanging from balconies, the perfect shot might leave Luisa Opalesky with bruises. After nearly two decades in New York, the photographer is as obsessed with a gritty city story as ever: “I love characters, and I will press my cheeks to the concrete to find them if I have to.” Big City Nobody, her debut book, was just published by Spotz, and it feels like a whirlwind day-in-the-life, from Interview outtakes to Canal Street chaos to hazy nights out on the town. It’s punctuated with writing by Daniel Arnold, Susie Essman, Teardrop, and Alissa Bennett, who came over after the release with some important questions for Opalesky about shooting unconsenting strangers and romanticizing the city’s squalor. “Young people need to learn how to fucking violate for their art,” Bennett exclaimed. But Opalesky’s charisma makes that easy.

———

ALISSA BENNETT: Luisa, do you think the fact that I love you so much makes this interview a violation of journalistic ethics, or do you think it’s fine?

LUISA OPALESKY: It’s a 33% violation, and I’m willing to go with it.

BENNETT: It’s 33% violation, but maybe we don’t care about that kind of thing anymore.

OPALESKY: No one gives a fuck.

BENNETT: I’m so excited to talk about your new book. How long did it take you to make it?

OPALESKY: It is about five years of work, during which I basically started shooting street photography for the first time ever.

BENNETT: I’ve thought for a long time that people can’t do street photography anymore, because I think everything looks like shit.

OPALESKY: You’re right.

BENNETT: Signage looks like shit, architecture looks like shit, clothes look bad…

OPALESKY: Cars…

BENNETT: I moved to New York in 1997, and I look at it now and I think, “It’s so tacky here.” Maybe it was always tacky, but I think you’re able to somehow look at the New York that we have now and show me parts of the New York that we had then.

OPALESKY: All of my favorite New York movies are from the ’70s and ’80s, and I think that I’m constantly trying to resurrect the parts of it that still retain that scum and that grit. It’s like I want to see cave grit. Mostly I love characters, and I will press my cheeks to the concrete to find them if I have to.

BENNETT: I think of you as a real New York photographer, by which I mean you have really devoted yourself to being a documentarian of this city at this particular moment in time.

OPALESKY: I don’t think I think about it that way, but I like hearing that.

BENNETT: When we first started talking about this book, you told me that your hero is Weegee, who was another New York photographer. That discussion really impacted how I encounter your work. In a lot of ways, I think this book is your love letter to all the people and places that we would rather ignore.

OPALESKY: I was born and raised in Philly, and I always wanted to be in the alleys photographing my friends. I always wanted to be on the oldest streets, the parts of the city that were kind of hidden. I’m always trying to find that in New York—those pockets of mischievous, dangerous shit—and I’m either going to find them, or I’m going to make them happen.

BENNETT: But there’s a balance that you probably have to make between your fashion photography or portraiture and the pictures that are maybe not necessarily as commodifiable as your more commercial work. How do you navigate taking pictures for cash when you really want to take pictures of dirt, loneliness, and abjection?

OPALESKY: It’s really, really fun to kind of bridge both and be in between it as much as I can. I think with the commercial work, it’s just about making sure I get both sides, and if someone’s not getting on the floor, I’m getting on the floor. I can use myself as a tool to negotiate that compromise.

BENNETT: Do you have a favorite photograph that you took that you can never publish anywhere?

OPALESKY: I mean, I have a slew of images where my butthole is in line with the stars. [Laughs]

BENNETT: A classic Luisa self-portrait. Go high, go low, avoid the middle.

OPALESKY: When I first started taking pictures, I was really interested in transforming myself into this solo act, femme fatale, rooftop dweller.

BENNETT: Say more about the rooftop dwelling, because you know I don’t approve.

OPALESKY: Well, I would get a beach towel and go to the highest point on my roof, which was kind of an acrobatic situation that would leave me with lot of bruises. I would just take a lot of pictures while standing on my head, balancing on the edge, that kind of thing. Your favorite.

BENNETT: I think when you first asked me if I would write for your book, I was like, “Yeah, but I really hate those pictures that you take where you’re on a fire escape and half your body is hanging off and there’s a blonde wig hurtling towards the ground.” And you said something to me that I thought was really beautiful and that kind of became the center of the text that I wrote for you. You said, “If you’re not afraid of falling, you don’t fall.”

OPALESKY: You don’t.

BENNETT: Is this a lifelong philosophy?

OPALESKY: I think it’s always been there, but I think that when I moved to New York, it became particularly apparent to me. In a tenement, you’ve got a maximum of six floors, and I’ve kind of always lived on the sixth floor.

BENNETT: When did you move here?

OPALESKY: 2007.

BENNETT: So, you got almost 20 years of walking up 6 floors?

OPALESKY: Fucking look at my ass.

BENNETT: Look at that ass. [Laughs]

OPALESKY: I could choke hold any man in this city with my thighs.

BENNETT: Sometimes I look at your pictures and I almost have to look away because the heights thing gives me such anxiety. Do you ever have the feeling like you could just decide to walk off of the roof? Part of what scares me is that it only takes like one second to be like, “Fuck it.”

OPALESKY: Yeah, but I’m totally driven by anxiety. All of my projects, all of my obsessions.

BENNETT: But this is also something that we really have in common, and I feel that this conversation is bringing us toward our mutual obsession with death. I don’t think it’s really with aging. It’s not like, “Oh, I have a wrinkle.” It’s like, “Oh, one day I’m gonna be fucking old.” We have a shared obsession with the elderly, this obsession with what happens to you as a person when you become the thing that you wanted to document when you were young.

OPALESKY: I can’t wait to get old!

BENNETT: I think anyone can take a picture of a young person and it looks great, because all young people look great, but I think that you are able to find that same glamour in someone who is 85. Luisa Opalesky loves a bitch living on public assistance who maybe hasn’t cut her nails in a while.

OPALESKY: Fucked up teeth, maybe a fungus…

BENNETT: Do you feel like a lot of the pictures that you take are selfies even when they’re not of you?

OPALESKY: Oh, yeah.

BENNETT: Because I look at this book and I feel like, in some way, these are selfies of strangers.

OPALESKY: I mean, they fucking better be, right?

BENNETT: But it’s what you do. The whole connective tissue of the pictures that are in this book is that they’re all of you. Tell me about this picture.

OPALESKY: This is one of the ladies on Mulberry Street off of Canal, trying to sell some handbags, some scarves. She’s got this white makeup on and I couldn’t tell she was wearing a wig or not. She was the most beautiful human being I encountered during the whole course of that whole day.

BENNETT: But why? This is my question for you, and maybe this is the miracle of photography. We have all seen women exactly like this; how come your picture of her looks like this and my mine wouldn’t? Do you feel like it’s the familiarity you feel for your subjects that makes them so beautiful? This image encapsulates what the real alchemy, the real black magic of photography is.

OPALESKY: Complete fucking alchemy. That’s the word, but I’m also really attracted to what I see a neglected kind of glamour.

BENNETT: What do you think the relationship is between glamour and the abject?

OPALESKY: I mean, I think that these characters are fucking rock stars. I think if you can see that in people, it makes you compelled by them, it makes you want to follow them. This happened to me earlier today; I fell in love with an older lady who was in line at the post office—I could not take my eyes off of her drawn on eyebrows, the makeup, the hair, and how everything was perfect in the light. I wanted to take a picture of her, I wanted to take a video of her, but instead I went up to her and I said, “You are so beautiful.” And she was fucking shocked. Like, just couldn’t understand why I would say that. And I was like, “Wow, you are breathtaking. Really beautiful.” And I just couldn’t do anything else. I could only look at her and say that, and somehow, it’s the same thing as taking her picture.

BENNETT: Do you think it’s important to have consent when you take a photograph?

OPALESKY: No.

BENNETT: I don’t either. Young people need to learn how to fucking violate for their art.

OPALESKY: Yes. I mean, it’s one second. Less than that.

BENNETT: And I think that if your intention is pure, then you get a picture like the one we just looked at. This person has never been more seen in her life.

OPALESKY: I want to plaster that picture all over the fucking world.

BENNETT: Do you feel like that’s something in your practice, “I’m going to take the picture of you that makes you feel like you’ve never been so seen in your life?”

OPALESKY: Yes.

BENNETT: And what does it mean?

OPALESKY: I really don’t expect everybody else to see it. I’m honored that you see it that way. I think that it’s a very small percentage of us that see it, and that’s why I have to take the pictures. You know, I think a lot of people would be confused by that picture.

BENNETT: Why do you think a lot of young photographers no longer feel comfortable taking pictures of strangers?

OPALESKY: Thinking too much.

BENNETT: They’re thinking too much, or they’re not believing enough in their affection for their subjects. I think that when you take a picture, you should feel affection or empathy, or why bother?

OPALESKY: And the intention should be like, “I have to do this, there’s no other option.”

BENNETT: You feel that?

OPALESKY: Yeah.

BENNETT: Like total compulsion. You have to do it?

OPALESKY: Have to do it. It’s really interesting to get to a point where you can differentiate the relationship with the subject from the relationship with the camera. You start to know when you need to just look for yourself, and when you’re supposed to actualize it in reality, materialize it in your camera. Sometimes I just want to see it in motion, sometimes I want to experience it as a human being with nothing blocking my face. And then sometimes I need to blast that face with a flash.

BENNETT: How do you get a great picture out of somebody?

OPALESKY: I think that a genuine disposition to want them makes them want you to do it. I don’t know, it’s really fast. It’s fucking speed of light, but I think the eyes really don’t lie. I don’t know. I love people so much.

BENNETT: What do you do when someone’s uncomfortable?

OPALESKY: I take a deep breath with them and I hold their hands sometimes. It’s so dumb, but it’s true. I hold my elder’s hands when she’s annoying me or when she’s moving too fast.

BENNETT: Who’s your elder?

OPALESKY: Ethel, who’s 91. Her desktop is so fucking crazy. And so sometimes I look at her and I go, Ethel, hold my hands. We’re gonna clean your desktop today.

BENNETT: And is she like, “I don’t want to.”

OPALESKY: And she goes, “Okay.”

BENNETT: Oh, I feel like I’d say, “I don’t want to.”

OPALESKY: [Laughs] No, she’s very easygoing. My previous elder was a bit of a battle axe.

BENNETT: But you have to explain who your elders are. This is a thing that I really love about you, that I think everyone else should really love about you, because it makes you so lovable.

OPALESKY: Last Thanksgiving, I really missed my dad, who is 86. And I took care of him for a couple months and realized, “Whoa, elder care is a crazy task.” It just requires so much patience. But it’s so great because you’re getting the real deal without technology and you’re getting stories. And all I want is a storyteller.

BENNETT: She loves a story!

OPALESKY: I love a performer and I love a good fucking storyteller, and the elders know how to grab attention because they want to talk.

BENNETT: Because they’re all narcissists. Just kidding. [Laughs] Not all elderly people are narcissists. But most of them are.

OPALESKY: The ones I like are. [Laughs] So, I was missing my dad and I went on NYFA, work was a little slow and I saw an ad for Companioning Elders Patrons of the Arts, and I thought, “This is it.” So, I did a phone interview, got it, and immediately started working the next day. In the interview, I happened to say, “You know, I can be a bit dramatic myself and—”

BENNETT: You?

OPALESKY: I can get a little overzealous about the type of elder that I’m looking for. I asked the employees if they had ever seen Scent of a Woman with Al Pacino. I wanted a blind, alcoholic, ex-vet. That’s who I said I was more inclined to vibe with, that I would have more of a connection with, than say, an Adam Sandler elder.

BENNETT: What if an elder was like, “Would you moisturize my hands, Luisa?”

OPALESKY: I would do that. I would also do a manicure. I would do light grooming. Light grooming is fun.

BENNETT: No feet.

OPALESKY: I’ve done feet.

BENNETT: Ladies and gentlemen, she does feet.

OPALESKY: I have done my father’s ogre toes.

BENNETT: Yeah, but that’s love.

OPALESKY: It really has to be.

BENNETT: That’s different. That’s real love. Speaking of which, I want to go back and talk a little bit about your affection for Weegee, because I think it’s really important.

OPALESKY: It is important. It’s my homage.

BENNETT: When we first started talking about this book, you showed me these really old Weegee publications, and they were not what I expected. We all know his crime photographs, but that is not your favorite work by him.

OPALESKY: Weegee’s People is my favorite book. And it’s linen bound, no photo on the front. Pictures like Bowery Savings, which is the image of a lady at a bar with a dollar bill in her stocking and her little crunched fat foot in a shoe. It won’t get better than that, ever. It won’t.

BENNETT: What is it about it? What is it about her and that image?

OPALESKY: It just so perfectly embodies the hustler. “I got it, I don’t need anybody to take care of me. I’ll fucking find my way.”

BENNETT: I live in a fucking tent. Don’t you worry about me.

OPALESKY: You’ll find me in a ditch.

BENNETT: I think half of you loves troublemaking, and the other half feels overwhelming empathy for the troublemaker who is down on his luck.

OPALESKY: I will not live a life without either.

BENNETT: It’s not like New York isn’t crawling with poverty and depraved situations, but there’s so much wealth here now, there’s so much plasticity. Identity has become so monolithic, so when you see something legitimate and authentic, if we don’t have you to take a picture of it, how do we even know it still exists?

OPALESKY: Oh, I love you so much. That’s why I’m out in these fucking streets. Being on the bike with the camera is a whole other level, because then you can really up the danger.

BENNETT: Because you can get away—

OPALESKY: Fast. I’m pretty good on the bike. I’m actually very good on the bike. I feel very confident, maybe too confident. Sometimes the bike is broken and it’s like, “Oh gosh, no brake,” but you know, we find our way. I also have roller skates that don’t have brakes on them. And it’s like, “Why the fuck would I have brakes on those roller skates?” They’re speed skates.

BENNETT: And I’m like, “Why the fuck would you go up on the sixth-floor balcony and hang your head and both of your legs off of it holding on with a piece of tinfoil and a fucking fake nail?”

OPALESKY: Your Instagram comments about the fire escape pictures have—

BENNETT: Inspired you to do it more?

OPALESKY: Buttered my fucking croissant.

BENNETT: Do you believe in the Ouija Board?

OPALESKY: Yes, I do.

BENNETT: Me too. Because they’re fucking real. If you were to reach Weegee on a Ouija board, what would you ask him?

OPALESKY: Oh my god. Let me really think about it for a moment.

BENNETT: You only get one shot.

OPALESKY: I mean, I kind of know what I would ask him. I want to know what he dreamed about. I want to know when he slept and if it was real sleep and what those dreams were, if they were daydreams or nightmares or night dreams. I want to know what the fuck he saw when he was asleep.

BENNETT: I’m going to come back with a real ouija board so that we can talk to Arthur.

OPALESKY: That light flickered, babe.

BENNETT: The light fucking flickered. That’s no lie. I hope his spirit isn’t trapped here, but maybe it’s fine. Maybe this is nice for him. Luisa?

OPALESKY: Yeah.

BENNETT: I love you so much.

OPALESKY: We just tried to make a Ouija board out of a piece of yellow legal pad paper and a pack of post it notes, and it didn’t work.

BENNETT: I’m coming back with like a legit Milton Bradley Ouija board from Amazon dot com.

OPALESKY: And I’ll bring the Molton Brown soap.

BENNETT: Does that make it work better? [Laughs]

OPALESKY: It’s a scent thing.

BENNETT: Goodnight, Weegee.

OPALESKY: Night, night.