IN CONVERSATION

Armando Alleyne Remembers Lunchtime with Basquiat

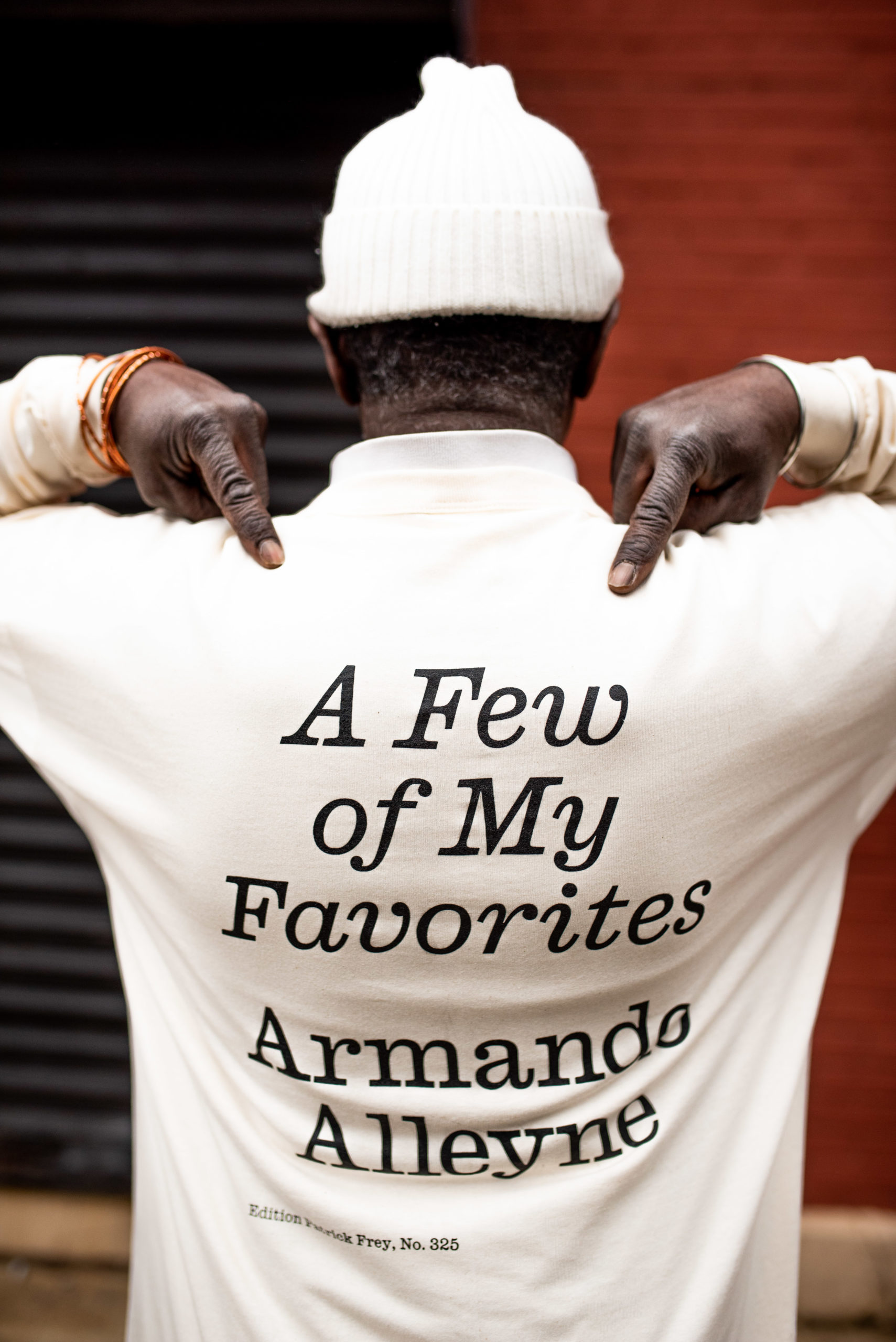

The New York City art world is a crowded one, crawling with visionary but unsung artists. Armando Alleyne never required any recognition to continue his lifelong painting practice, but last year his first book, Armando Alleyne: A Few of My Favorites, launched to international acclaim. Published alongside an essay by the Philadelphia-based conceptual artist Tiona Nekkia McClodden, A Few of My Favorites was awarded the Most Beautiful Swiss Books award, an honor bestowed by the Swiss Federal Office of Culture for notable achievements in book design. The celebration continues with a special edition t-shirt, made in collaboration with Other Means, the book’s designer. Fresh off this well-deserved distinction, Alleyne caught up with his longtime friend Michael A. Cummings, a contemporary quilter who lent photographs of a young Armando to A Few of My Friends. Together, they chatted about Basquiat, chance encounters on the New York City subway, and discovering the music of Stevie Wonder and Thelonious Monk while living in a homeless shelter. —LAURA SEREJO GENES

———

MICHAEL A. CUMMINGS: Tell me, since you grew up in New York, what sort of influences affected you when you were younger to lead you into the community of art?

ARMANDO ALLEYNE: When I was growing up, my parents and my teachers were introducing me to people like Matisse, Picasso and some Romare Bearden but more so the European artists, the impressionists such as Manet and the impressionist movement. So I got that influence and then I started thinking for myself as a little kid and as a teenager, “How am I going to put these ideas together?” And I kind of like the whole idea of collage—the painting part and gluing and putting fabric or paper together with the background or the foreground to create a total piece.

CUMMINGS: Let me interrupt you right there. Since you were young at the time your parents were showing you all of that, did they encourage you to become an artist or did all your siblings get that same experience?

ALLEYNE: My sister and brothers, my older sisters, they encouraged me to be what I want to be. My father admitted he would love it if I were a doctor or lawyer or a surgeon. My mom encouraged me as time passed. But at first she was also like my father, in that she wanted me to be an architect, engineer, doctor, something along that line, more of a professional type.

CUMMINGS: Were you taking art classes?

ALLEYNE: Well, the thing that occurred when I was in high school, I went to City-As-School, and I thought of taking drafting. I thought—it’s kind of related to art and I kind of like to draw things that I could build. I figured I’d go into architecture. In my third or fourth year, I switched it up and decided to go into fine art. The art parts of drafting weren’t enough for me.

CUMMINGS: At that point in high school, you had an internship. That internship brought you over to the Children’s Art Carnival, right? And that’s where we met. So give me your impressions of how we met.

ALLEYNE: Children Arts Carnival, run by Harlem artist Betty Blayton Taylor, as an outreach program of the Museum of Modern Art, had all types of people passing through—you might see Stevie Wonder passing through. You might see Dizzy Gillespie, you might see Mayor Koch running through there, Charles Rangel running through there! Children’s Art Carnival was at the forefront because schools were cutting off funds for art programs, cutting off creativity. And Children’s Art Carnival was at the forefront saying, “No, give your students some creativity, help integrate creativity into the classroom, work it into the mathematics and the history, and help them grow from that!” Betty Blayton Taylor had an approach and a philosophy about this. And so she was bringing that to the Black community. And the Black community was generating a lot of exposure and a lot of great criticism was going back and forth; a lot of good energy was coming out of it. Creativity was coming out of it and helping the community. It was situated in Harlem, Hamilton Terrace.

CUMMINGS: There was someone else in your class that was very famous…

ALLEYNE: Jean-Michel Basquiat. He was also doing what we call a semester or term at Children’s Art Carnival. We used to sometimes joke with each other at lunchtime. Who knows what would have happened, who he would have become? Maybe he would have become the director of Children Carnival or Studio Museum, if he had lived.

CUMMINGS: Those positions take a lot of administration sort of mindset. In addition to being an artist, I worked at the Department of Cultural Affairs so I can tell you from experience. I think Michel was more of a creative spirit; to make art rather than shuffle paper.

ALLEYNE: Right…

CUMMINGS: There were some other artists that went through there also, but not as students. They came over because Betty Blayton Taylor was very generous in terms of hiring unemployed artists. And a lot of artists came from the Studio Museum Residency program to help her out: Whitfield Lovell, who’s become a very famous artist. Even David Hammonds came over there a few times and also Fred Wilson, he came through there as well. So it was a very popular place in Harlem for a lot of new energy going on at that time.

I remember you as tall, skinny and very curious, serious and interested in what was going on. And that was not common. A lot of students and people came in, came in and ran out real quick. That was just a little side thing they had to do. But you really want to apply yourself and get into learning about things. And that impressed me a lot about you.

After that I invited you to my studio down in the Village, and I think you started to kind of rotate down by my place when you would be in the Village area. I lived on the corner of Gansevoort and Horatio; now that’s the location of the Whitney Museum. I would show you what I was doing at that point. I was starting to work with fabric and I had bought myself a sewing machine and I was showing you a lot of things. And then also I was starting to collect African art. And I don’t know if prior to that you were into African art…

ALLEYNE: Well, I was observing it, but I’m still living at my parents house at that time. When I was able to go to school at City College that made me branch out and start thinking about what I want to do, what I want to collect, what I want to be, et cetera et cetera. We grew up in the Lower East Side, and I grew up in the projects, and there were ten of us. Me, Garfield, Ricky, Melanick…Garfield was in the living room. Me, Ricky, Melanick, Abel, Crim were in one bedroom. So it was hard for me to think about putting anything else in there because it’s like beyond my body’s sense of personal space. Half of the time we were stepping on each other’s necks, on each other’s case about what-goes-where, how to organize stuff…

CUMMINGS: I can only imagine because all the boys were like giants! 6’-3”, 6-4”, 6-5” or something. I mean I met your brothers and wow!

ALLEYNE: [Laughs] But when I branched out, I decided I wanted to also collect art and collect and create art and be known for art. And I started thinking about what my style was going to be like.

CUMMINGS: Right…

ALLEYNE: City College pushed on me. Abstract, okay. That seems to be like the flows, the current flows, the times, the 70s—the abstract. Even though I had done basic and realistic drawing, when I started dealing with painting, I dealt with abstract. And originally I spent maybe one and a half to two years doing oil painting. And then something happened. My system broke down and I found out from the doctor that I’m allergic to oil paint. And that’s when I had to switch to acrylic paint.

CUMMINGS: Yeah, I started off also with oil paint in Los Angeles and found out it was just too toxic for me because I have asthma. And that really turned that on. And that was a no-no. So I changed over to acrylic paint as well. So you finished College and you went on to do what?

ALLEYNE: Well, when I finished College, I went on to painting. I went on to teaching at the same time. But a couple of things occurred. A good friend of mine, Mark Stephen, dear, had passed, and that made me go into a depression…

CUMMINGS: How long have you known him and what did he die from?

ALLEYNE: He died of AIDS. And I happened to have known him a good eight, nine years, maybe a decade.

CUMMINGS: I know you kept in touch with his mother after he passed.

ALLEYNE: Yes, I still do. I called her the other day, his mother, Geneva dear, she’s in her 90s now.

CUMMINGS: Did you get over it quickly?

ALLEYNE: Well, I got over it in one sense, but the way I got over it was to go “run away” to Chicago. And then when I came back, I felt like I was depressed again and I didn’t want to be in my apartment. So I went back to my parents house. But it wasn’t long before that that I became homeless. And it was partially because of the mental depression that was going on by the lack of that friendship and support, that spirit that was there before, possibly because that spirit was connected to a tree of spirits that was slowly disappearing because of AIDS. Yes. It just made me feel like everywhere, left! right! all the time, someone is dying. My sister catches HIV… and then she’s positive and she’s dying…it’s all overwhelming for me.

CUMMINGS: Now, you had all these personal experiences, and I know they translated into your compositions that you created in your paintings. So were you painting at the time that you were going through this depression or were you holding on to those memories?

ALLEYNE: I was drawing mostly because at the time I was living in a shelter. And a lot of stuff that I did was taken from me. I don’t know how to explain, but they have certain rules. I used to have no place to store things except a locker.

CUMMINGS: I see.

ALLEYNE: I stored too much paper in my locker; it was considered a fire hazard. So then I just tried to think about getting away with it by storing it either between the sheets or underneath the mattress… which they also considered a fire hazard. They used to take it all away no matter what I tried.

CUMMINGS: What year was that?

ALLEYNE: Oh, that was like in the 80s, going into the 90s.

CUMMINGS: I did meet you one time when you were homeless. You might remember that I saw you on the train and I brought you home.

ALLEYNE: Yes, I remember…

CUMMINGS: How did you pull out of that?

ALLEYNE: I basically pulled out of that through a program called CSS program [Community Service Society]. And I was able to get myself together again and back into an SRO [single room occupancy]. But by that time, I had decided I wanted to do art again, the freedom and the liberty as far as what I want to do and not be worried about works being stolen, taken, just disappearing in the middle of the night. Or if I’ve gone for one day and come back, it won’t be there necessarily. So I was able to start developing this kind of painting collage again. But it was in the 90s, going to the early 2000s. And this was when I was living on White Plains Road [in the Bronx] and then again when I moved to Sedgwick Avenue.

CUMMINGS: And what were some of the series that you started to create?

ALLEYNE: The shelter blew my mind about music. At the shelter we were listening to Thelonious Monk, Stevie Wonder…

CUMMINGS: And this was all in the shelter?

ALLEYNE: They played things like Biggie Smalls. They put on things like R. Kelly, Wu-Tang Clan. So it opened my mind to pop music, rap music. What’s her name? Mary J. Blige, for instance. People like that, Missy Elliot, you could say. But in my own personal circle, as far as my friends, I used to collect people like Thelonious Monk, Eddie Palmieri, Mary Lou Williams. At that time, there was a place called Tower Records and I would go there with the extra money and get some CDs to listen to in my apartment. The series that I started was revolving around the music that I had.

CUMMINGS: And this is what you listened to?

ALLEYNE: So the series that I started with were, like, people that I was listening to, like Thelonious Monk, Bird, Charlie Parker, Charles Mingus, Duke Ellington. So I started painting the main musicians that I was listening to at the time. And then later I branched out.

CUMMINGS: So in your book, in addition to all the portraits of musicians, you have a lot of series… there’s a series I like called Shelter Blues. Let me tell you, it reminds me so much of Jacob Lawrence’s paintings. But you have a little cat at the bottom of the composition. I can see the blues and the isolation but then you put a little pet in there! The company for that individual. What was all of that about?

ALLEYNE: Well, before I was in the shelter, I did have a cat!

CUMMINGS: I remember you had cats! Do you have a cat in the studio?

ALLEYNE: Not now, but when I lived on Convent Avenue, I had a cat. When I lived uptown, I had a cat. When I lived in the Bronx originally, I had a cat. When I moved to Fordham Road, I had a cat. I was sometimes dog sitting a Husky, and so that was that.

CUMMINGS: So how did the cat end up in the Shelter Blues?

ALLEYNE: Well, I was thinking… well I have to tell you the whole story. It’s a love story.

CUMMINGS: Of Shelter Blues?

ALLEYNE: There’s a love story. It’s really like this projection of a friend of mine. I never knew if he was straight or gay, but he would just come and sit on my bed…

CUMMINGS: In the shelter?

ALLEYNE: In the shelter! We would just talk. Then they would say, “Sir! You cannot sit on another person’s bed! Get up!” And that was that. But in the back of my mind, I was thinking about myself being homeless, himself being homeless… what were we going to do? What were we going to do to make sure we get ahead in the world? I couldn’t see myself being here at that point because I was so hopeless. But I’ve dedicated the Shelter Blues to him.

CUMMINGS: Well, it’s interesting that we’re kind of talking about the cat and that you owned so many, because now I’m kind of thinking of all the different compositions. And you have a cat, a form of what looks like a cat in a lot of your compositions.

ALLEYNE: I portray animals in my artwork because they represent the missing spirit, the missing person that was there. The animals that I couldn’t have anymore, I portrayed them.

CUMMINGS: There’s another painting or I think it’s a drawing, called Dreaming. Remember, it’s two guys that look like they’re on the beach or something. When I think of the word dreaming, I think it’s a mental sort of thing, and it’s not very clear how solid the environment is in the paintings. So it’s almost like they’re floating and you can’t tell if they’re on the beach or in the air, in the water. What is that about?

ALLEYNE: That piece is sort of like a surreal, erotic dream.

CUMMINGS: Oh! I didn’t get the erotic part.

ALLEYNE: No, I’m just saying it’s sort of like the hand of one person reaching towards the other person. It could be that he just happened to be asleep and his hand fell there, or he could be reaching for something. It’s like an erotic impersonation coming on there. And then the whole thing about the beach, in my existence… when I went to the beach, afterwards I used to have these strong dreams, thinking of doing this and that. And then I would wake up and think—that was a strong dream! I don’t know why. Sometimes the shelter would take us on these excursions, to Jones Beach and I would have these dreams at night, like my mind being transported somewhere else…

CUMMINGS: And some of these art works are featured in your new international publication, your fabulous one-of-a-kind book! What do you think about it?

ALLEYNE: I think it’s great—it’s great! I just love the cover. I just found out that we have the T-shirt of the cover, and I think it’s fabulous. I pulled the work together as a little collage of Biggie Smalls—simplification of the lips, the nose and the glasses and the face, as opposed to that piece there, which is also Biggie Smalls but a painting.

CUMMINGS: And I own one of your paintings as well of Biggie Smalls.

ALLEYNE: Yes, you do!

CUMMINGS: When did you do that collage of Biggie that is on the cover?

ALLEYNE: I started it right after he passed, 1997.

CUMMINGS: Everything that I see is basically painted, and that work is a collage. So what led you to create that particular composition?

ALLEYNE: Well, I was experimenting first with the idea of rap music being fortifying. I had used the Tropicana carton, the orange juice Tropicana carton with Biggie Smalls in one figure. And then I said, “why don’t I do Biggie Smalls’ face close up in collage,” on a small piece of page, similar, but not so large, maybe eleven by 11” by 14”, 11” x 17” and see what happens.

Produced and edited by Laura Serejo Genes.

Armando Alleyne’s book and shirt will be available for purchase from the Edition Patrick Frey booth at the New York Art Book Fair from October 13–16, 2022. You can also purchase Armando Alleyne’s special edition shirt from o-m-books.com. You can catch Michael A. Cummings’ work this Fall at Carracci Art in Tribeca through November 5th.