ART

Amy Sherald and Thom Browne Discuss Devoting Your Life to Art

“Michelle LaVaughn Robinson Obama, 2018, oil on linen.” That’s the caption for Amy Sherald’s most famous painting to date—which is also, to date, the most famous painting of the 21st century. The 47-year-old, Georgia native sprang into the limelight in 2017 when she was commissioned by the National Portrait Gallery to create the official portrait of the former first lady. Being awarded such a monumental commission was very much a personal win for the artist, who had already achieved success—if not exactly fame—for her stark yet vivid figurative oil paintings of Black subjects, often positioned staring straight ahead in the canvas’s center foreground, still as statues, possessed with awe, defiance, and beauty.

But the project also signaled a shift in social consciousness, about how contemporary art can function in the public realm—that it can indeed marry politics with aesthetics, message with form, that it can be egalitarian but also push boundaries. The result, which shows Obama seated in a voluminous white gown, gazing out at the view with her hand at her chin, set against a monochromatic powder-blue background, is nothing like the other bureaucratic oil paintings hanging in the White House. And for good reason: Obama was nothing like the other first ladies, before or since.

The presidential portrait was the kind of once-in-a-lifetime endeavor that makes an artist’s career, but it comes at the risk of defining it so completely that it over-shines each piece that follows. Thankfully, Sherald didn’t waste any time proving that Obama was but a single canvas in a long and fascinating investigation of Black subjects rendered in her signature grisaille skin tone and dressed in eye-popping patterns and colors. Sherald staged a blockbuster 2019 exhibition at Hauser & Wirth in New York, and this spring she’ll open her first West Coast solo show with a new series of paintings at the Hauser & Wirth outpost in Los Angeles. The artist, who says she moved from Baltimore in 2018 “for love” and lives and works right across from Manhattan in Jersey City, often finds her subjects by walking the streets or taking the subway. Struck by a sudden, overwhelming fascination with a particular individual, she then invites them to her studio to take their photograph and uses that image to build her works. Sherald’s painting aesthetic is so deceptively clean and straightforward, with such a matter-of-fact authority, that it belies her painstaking process. One of the great delights of looking at her work is the way she paints clothing. It should come as no surprise that she often looks to fashion designers for inspiration, one of her favorites being Thom Browne (Obama almost ended up immortalized in one of his floral suits). The two had never previously spoken, but this past December, they connected to discuss devoting your life to art, with or without a backup plan. —CHRISTOPHER BOLLEN

———

AMY SHERALD: I’m so nervous to talk to you. I was told you aren’t very chatty, and I was like, “I’m not either!” This conversation is an introvert’s nightmare.

THOM BROWNE: I’m nervous, too!

SHERALD: What have you been working on?

BROWNE: Right now, I’m working on my show for March. I don’t know about you, but being able to get things done has been a challenge. I keep reminding everyone to look to what we can do as opposed to what we can’t, and move in that direction. How has the past year affected your approach? Has it made hunkering down and working harder or easier?

SHERALD: I think it’s actually made it a little easier. I was in Atlanta for the first four months of the really hardcore shelter-in-place order, and away from my studio, but I was able to do some drawings. And I hate drawing. I’m not a sketcher! My sketch is the photograph. But I decided to challenge myself, since I had time to fail, to do some gouache paintings on paper. It was absolute torture for the first week, but then I really got into it. I had to get over the hurdle of being intimidated by the fact that I can’t control it, because it’s very different from oil in that if you make a mistake, you can’t start over. If I do a painting and it gets damaged, I don’t feel like I can make it over again. It feels different, like the emotion leaves when I’m done with a painting. Anyway, since I have this exhibition in L.A., I hit the ground running when I got back to New Jersey.

BROWNE: Are you a disciplined artist or do you need a deadline to get things accomplished?

SHERALD: I like a regimen. I like eating at the same place every day. I like a uniform. I usually pick one thing that I’m going to wear for a year, and I wear that every day. Last year it was a denim jumpsuit. I don’t like to have to think about anything else. I like to wake up at the same time and walk my dog—now I have three—and get to my studio at 9am. I like to leave at 6 pm if possible so that I still get to have an evening with my partner. Before, when I was single, I would just work until I was tired, which would be closer to 10:30 or 11. But now I like to be home with him and have dinner and watch whatever we’re watching on Netflix and just kind of chill out and enjoy life.

BROWNE: Balance is so important, even for the quality of the work. I think it’s easier to be productive when there’s a schedule. I personally love when the day ends, and I don’t know about you but a drink is always needed.

SHERALD: Absolutely.

BROWNE: When do your ideas come to you? For me, when I purposely sit down and try to design something creative, it never comes.

SHERALD: For me, it comes when I’m living—just being on the subway and turning and seeing somebody. In an instant, I know that this person has to be my next subject. I just have to work up the courage to approach them and have that conversation. I think that’s part of the reason why I do so few paintings a year—usually between 10 and 12. It’s really hard to find those subjects. There’s something about them, an energy that translates into the painting. I wait to find that right person and there have been times when I’ve missed the opportunity for whatever reason, like I talked myself out of it, and I usually lament over it for years.

BROWNE: Are clothes a part of what attracts you?

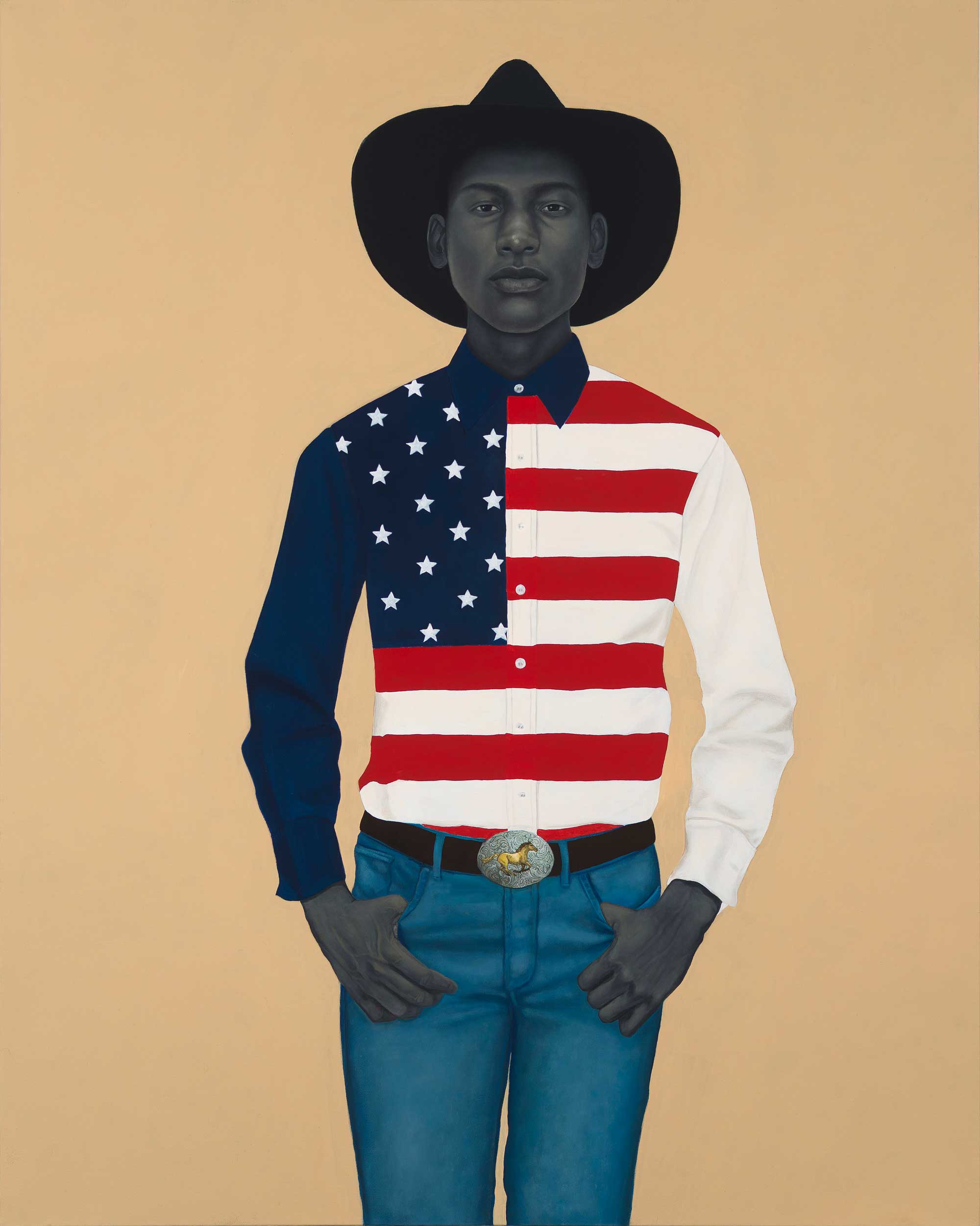

SHERALD: I remember in some early paintings, where I was trying to extricate Black people from the historical narrative that has so often framed them in this country, I was looking at different costumes and clothes. I looked at Alice in Wonderland. I did a painting with a codpiece that was inspired by A Clockwork Orange. One of the very first ones I did was called “Pony Boys,” and it had this jacket with a pony coming out of it. Clothes resonate with me on such a deep level, and it took me a while to learn how to use them.

- “What’s precious inside of him does not care to be known by the mind in ways that diminish its presence (All American),” 2017.

- “Listen, you a wonder. You a city of a woman. You got a geography of your own,” 2016.

BROWNE: Did you ever think of becoming a fashion designer?

SHERALD: I never really feel like I discovered fashion. I was really a country bumpkin from the South, and I remember my friend who worked in fashion telling me who everyone was. The more I learned about it, the more intimidated I was, honestly. I curate these looks that I use for my paintings, and I’m really good at that. But outside of that, when it comes to fashion or interior design, I start to doubt myself. But my imagination definitely gets sparked by movies and fashion more than it does by other artists.

BROWNE: Watching a movie can be the catalyst for a new painting?

SHERALD: Absolutely. The movie Big Fish triggered the whole body of work I’m doing now. I watched that movie and I wanted those kinds of frivolous narratives. Black people just haven’t really been afforded that kind of representation. So when I saw that movie, it really clicked for me. I want to make work about Black people just being Black, and I liked embodying that idea of fantasy.

BROWNE: What I love about fantasy is transporting people. You can remake the world as it should exist.

SHERALD: I don’t know if you know this, but when I was working on the portrait with Michelle [Obama], I was looking at your 2017 collection that had a black suit with a print underneath and big flowers on top. That’s one of the outfits I really wanted to paint her in.

BROWNE: Michelle Obama is amazing. How was your experience with her? Were you nervous?

SHERALD: I was nervous, but she takes all the nerves away because you’re like, “Oh, she’s just like the rest of us, except she was the first lady and the first Black first lady! But it was really comfortable. I only had an hour to photograph her. And then I had another hour, two months later, to photograph her again. It was really smooth and easy. She gave me creative freedom and I was able to do what I wanted. And it was definitely fun.

BROWNE: How often do you go to Washington to see the portrait?

SHERALD: I’ve been up there maybe three or four times incognito. I still get anxiety thinking about it. Making a painting for a person, an icon who is globally embraced, is scary because you just can’t make everybody happy. It was one of the highlights of my life, but when I think about that year, I wouldn’t want to do it over. There was so much intense focus on me for such a long period of time. For the first week or two, there was crazy media attention. Then things calmed down. Then the trolls came out of the woodwork until they finally got bored and moved on to something else. And then, finally, I was able to really enjoy it.

- “The girl next door,” 2019.

- “Handsome,” 2019

BROWNE: That’s the social-media world we live in now. How do you navigate that part of life?

SHERALD: Probably every other month I’m like, “I just want to delete everything.” But I haven’t yet because I’m addicted. I don’t have a Facebook account, but I have Instagram. I really like looking at pictures. And especially now during COVID, I can follow a hashtag and get images that I might not have had access to otherwise. So it’s been beneficial. Especially with this show, I had this idea of a playground and I was trying to find something that worked but instead I landed on an image of a person walking with a surfboard. So I did a 180 and changed the whole production for that one painting based on that image. I can’t be out on the streets now, but I’m still able to look at things thanks to social media. But my niece is on it and it’s a nightmare. I’m always putting out fires with her. I don’t think you should be allowed on Instagram until you can legally drink.

BROWNE: I think, for the generation that has grown up with it, it’s affected their ability to be truly and purely creative. There are so many references available that there’s no closing your eyes and thinking of something new.

SHERALD: I mean, the idea of thumbing through a book? My creative process used to be going to sit in the library for three or four hours and just looking at different books and waiting for something to hit me. That’s very different from this instant access that a lot of young people have. I had to really use my imagination growing up because all I had were encyclopedias. When people ask me what my influences are, I say myself because I don’t like to keep things in front of me while I work. I work from the inside out. I try not to look at art when I’m making my own work. That’s especially true for the individual portraits. They all face the same direction. I call it “the missionary position”—and I think you use the same position in your work. I like my models to stand facing forward, straight up and down with only a little shift here and there. It gets challenging to make each one of those very special when they’re all very much the same.

BROWNE: I can’t stand having things around when I’m working. I find other images lying around crippling. It’s the notion of being forced to create things that people want as opposed to me giving them things that I think they should see. I think the reason you’re successful is that you’ve created something no one else can do. I bet your parents are over the moon about your accomplishments. Did they understand your wanting to be an artist when you were growing up?

SHERALD: They didn’t understand what it meant to be an artist. Even now, my mom only kind of gets what I do. They’re not museum-goers. My mom is 84 and she was born in 1935. That’s a very different reality. My being an artist, it’s like she’s still afraid that people are going to run out of money and stop buying my paintings. I’m like, “Mom, I’m past that now. I have a blue-chip gallery and everything’s going to be okay. I am your retirement plan and it’s working out.” Actually, there was a lot about my mother that I didn’t find out until quarantine when we were stuck together in a house for five months. My birth home was in Columbus, Georgia, so we drove down there to check her mail and my partner came because he wanted to see where I was from. She gave him a tour of the house and spoke about it in a way that I’d never heard her speak, like about her design choices. She was really into furniture and explained why she chose the colors. And there was a little room that was supposed to be her painting studio. I never knew that. Some of the paintings in our house, she never told us, were her paintings. There’s a painting in the kitchen of a really beautiful still life with these colorful glass vases that she painted. So now I feel like I’m an extension of her life, like she had children and didn’t see art as a realistic way to make a living, because she had no one to look at to understand that it was something that she could do. Neither did I for that matter, but I do feel like painting is what I was born to do. I didn’t go to a museum until I was well into my 20s. It’s not that I was nurtured into art, it’s just who I was born to be.

BROWNE: I never really got to speak to my parents about how they influenced me. And they influenced me so much more than I realized.

SHERALD: When I think of my childhood bedroom, everything was matched perfectly—like the baby-blue carpet, the bedspread, the curtains. It’s much like the tightness I have in my work. I like the images to be pristinely painted. I think that part is my mother, because everything in the house had to be perfect. I couldn’t put posters up in my room. Everything had to look like it was in a magazine all the time, and, even though that’s crazy, a lot of that was about who we were in society as a Black family in Columbus, Georgia, where my father was one of the first Black dentists. Presentation became everything. I’m not sure my mother fully understands that connection between my work and my childhood.

BROWNE: The best part about family is that they never really understand what you do, and that’s okay. There’s something really refreshing about that.

SHERALD: And most of the time it’s really funny. My partner, Kevin, jokes that his mom thinks he’s a bank teller, even though he works with hedge funds. But I really, truly understand that I’m here in this life to make art, and I think it’s what has kept me so steadfast on this path. I knew I should be doing art even when I wasn’t the best at it. I was not the best painter in grad school. I’m sure everyone I was with in grad school is probably shocked that I’m here because I had the least talent. But I worked really hard and was determined to do this. I saw no other vision for myself. Luckily it worked out.

BROWNE: In 2009, I almost went out of business. And I thought to myself, “I don’t know what I will do if this has to close, because this is the only plan.” Do a lot of young artists ask you for advice? What do you tell them?

SHERALD: Yes, and no matter what I’m doing, I try to make sure I stay available because that is really instrumental. I’m really honest about my answers: “It’s not easy. There’s a good chance you’re not gonna make it. It’s an impossible career to try to pursue. Galleries still want to feel like they’re discovering you—like you’ve been working in this wretched dungeon and nobody knew you were there and they pulled you out into the light—but if you are perceptive enough to look at your contemporaries, look at your surroundings, look at art history, you can figure it out. My advice is to think, ‘What would I be if I were in conversation with all of these people whose work I admire?’” My paintings are exactly my personality, but I want everybody to feel included in them. There’s a bit of a people-pleaser in me, and I think that finds its way into the work. Even when that’s translated to color, I don’t like conflict.

BROWNE: How do you feel about the commercial aspect of the art world?

SHERALD: From the beginning, I put my foot down and said, “I’m going to produce the amount of work that I am inspired to do on an annual basis and not get sucked into the frenzy of art buying. I am not going to become a luxury brand.” I call myself a late bloomer. I have been doing this for a long time, but things really started to pick up in my late 30s and early 40s, at which point I’d had the opportunity to watch other people in their careers. I’m really happy that I wasn’t in my 20s when the whole world exploded. It’s really easy to get caught up and for your head to get really big. You lose focus on the things that are really important in your practice.

BROWNE: Do you know all the collectors who own your work?

SHERALD: I don’t know them personally, but I get a name. I know a name and a location for the most part, unless it’s gone to auction. When a work goes to auction, it’s kind of lost to the universe.

BROWNE: How do you feel when somebody owns a piece and then turns around and sells it at auction? [At the time of this conversation, Sherald’s painting The Bathers had just sold at auction for a record $4.5 million.]

SHERALD: It’s a liquid asset and it’s not great, but it’s just the way business goes. I was trying to explain this to my mom the other day, because I had a piece go up to auction and I was like, “Mom, it’s like buying a house in a neighborhood that got gentrified. You bought the house for $150,000 and the neighborhood was gentrified and now the house is worth $2 million. You don’t have to go back and give money to the person who you bought the house from.” But I think because so many artists are struggling when it happens, it’s like, “Wait, that’s not fair.” It can feel very personal, but it’s not personal. It’s just the way it works.

BROWNE: You mentioned earlier that you have three dogs. What kinds?

SHERALD: I have a Jack Russell Pekingese that I rescued in Baltimore. His name is August Wilson, named after the playwright. Then we unexpectedly adopted two albino Pekingese in Atlanta during COVID. Nobody needs three dogs, but it just happened. They’re super cute and they need a home. We named them George and Weezy after The Jeffersons. They’re all crazy.

BROWNE: Our dog is crazy and we love him and he gets away with murder.

SHERALD: I sell paintings just to pay for August to go hiking. He’s living his best life.

Artwork Copyright: Amy Sherald, courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photographed by Joseph Hyde.

———

Photography Assistants: Jimmy Kim, and Jordan Zuppa