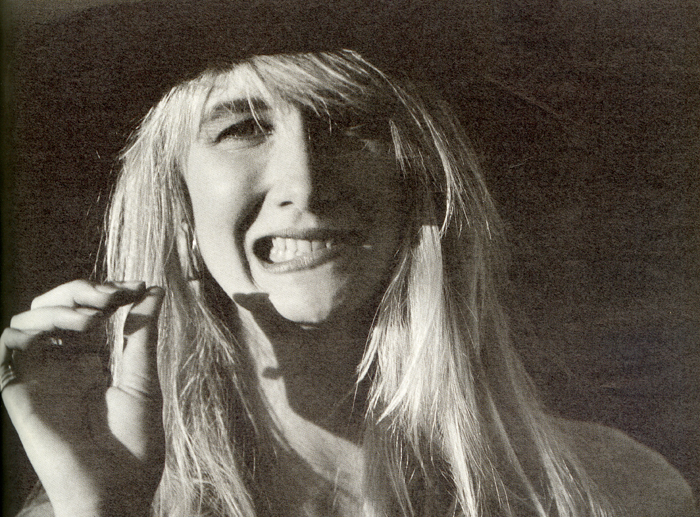

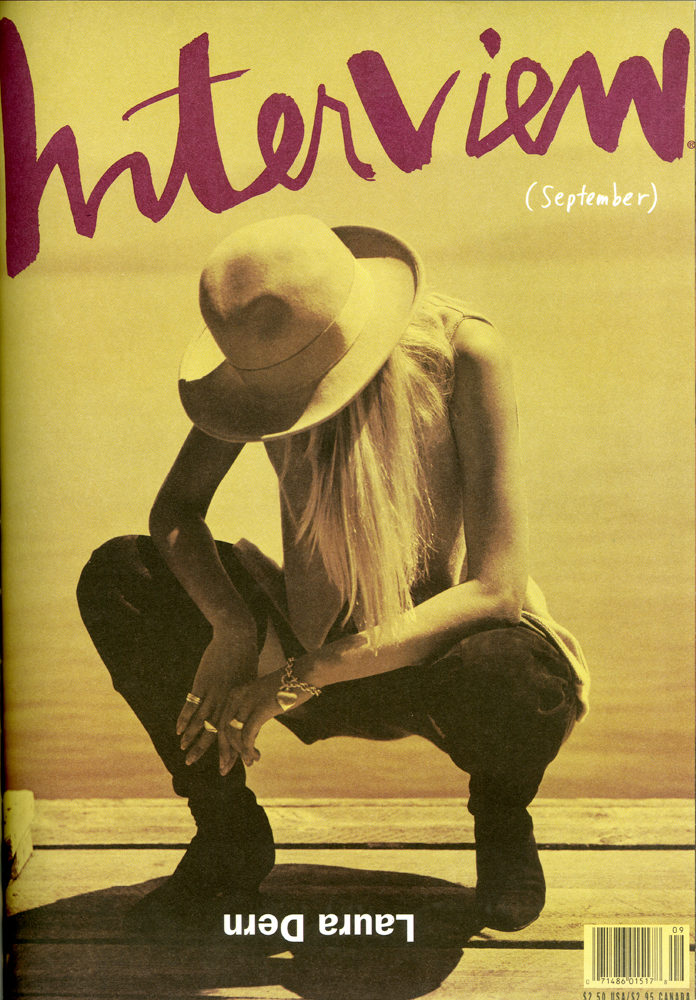

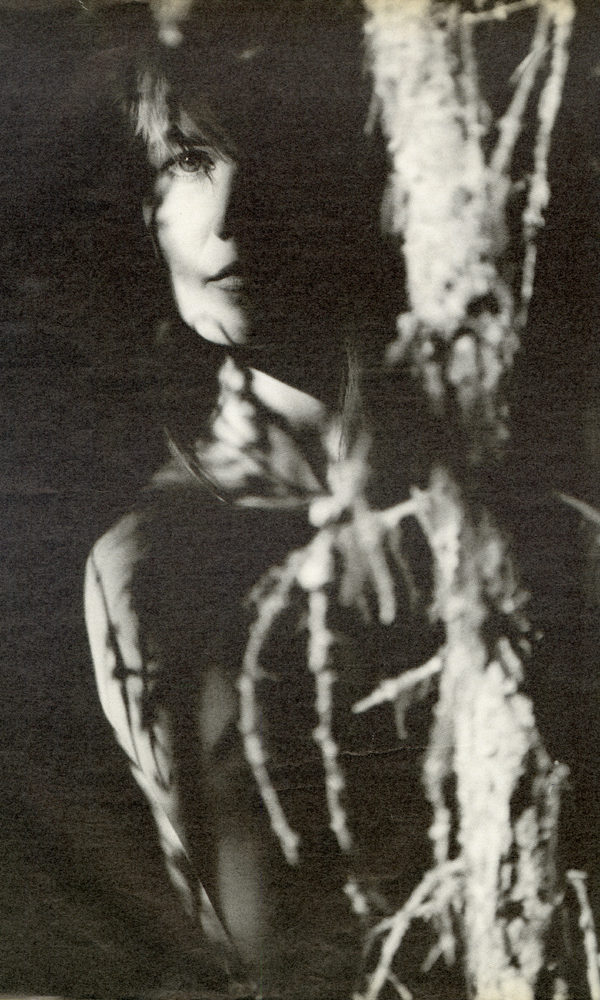

New Again: Laura Dern

In 1985, when filming Blue Velvet, director David Lynch gave German photographer Peter Braatz exclusive behind-the-scenes access. Bratz released a surrealist short No Frank in Lumberton (1988) using part of the footage filmed on set, but a forthcoming documentary, Blue Velvet Revisited, will use unreleased footage in a more straightforward approach. Although there is a trailer for the documentary, there have been few updates regarding its release since the announcement of the film nearly a year ago. So while we wait for more information, the soundtrack for the film will have to suffice, as it provides a sonic glimpse of what’s to come. Released in the U.K. last October, the soundtrack will be available in the U.S. starting Friday and features original songs by Tuxedomoon and Cult With No Name. In light of its release, and while anticipating the film itself, we decided to revisit a September 1990 interview with actress Laura Dern, who, at the time, was promoting another Lynch film, Wild at Heart.

Laura Dern

By Gary Indiana

In the course of a film career that began at the age of seven, Laura Dern, the daughter of Bruce Dern and Diane Ladd, has grown up into an actress with a supreme gift for edgy, multi-textured roles. She has charted the territory where innocence and dark reality meet and mutate into unpredictable forms of life. Dern’s characters are never simple. They contain lurking contradictions, mixed feelings, the jumble of motives and impulses present in every person. In David Lynch’s new film, Wild at Heart, Dern plays Lula, a sexually wise, rebellious, quirkily tough and vulnerable girl from North Carolina who hits the road with her lover, Sailor (Nicolas Cage), pursued by a small army of gargoyles hired by her mother, Marietta (Diana Ladd), to bring Lula home. Dern’s performance is something to burn your fingers on—raunchy and passionate and anxious and sweet.

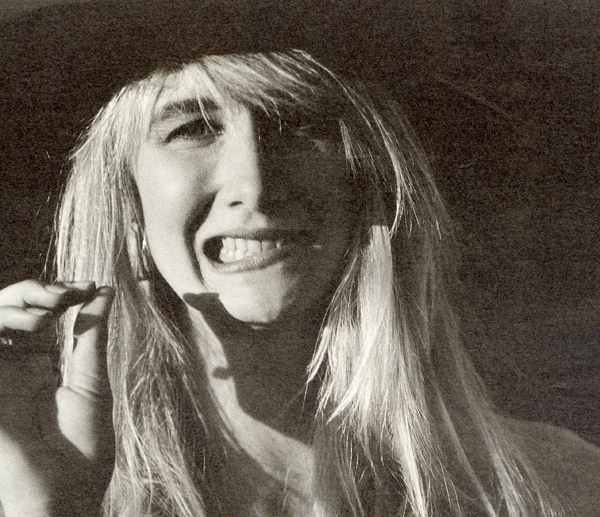

“I wanted to go to Jupiter,” she says. “That was my plan from day one, and David gave me the ticket.” We met at Ivy at the Shore, in Santa Monica. Laura Dern arrived in a very summery white Azzedine Alaïa dress and no makeup, looking southern California beautiful rather than movie-star beautiful. In person she is quick, spontaneous, droll, and not even slightly inhibited by the presence of a tape recorder.

GARY INDIANA: Where did you go to school?

LAURA DERN: Here in Los Agneles, in the Valley. A very college-preparatory high school. Before that I went to a Catholic school. The private school was good—the teachers wanted all of us to have the freedom to think for ourselves. The education was good at the Catholic school, but you only got that one ideology.

INDIANA: I went to a Catholic school in New Hampshire, which was scary.

DERN: Private boarding schools and Catholic schools on the East Coast are something. Choate really ruined my father’s life. He’s had nightmares about Choate every since he went there. Treat Williams, who’s a good friend, went to Kent School, in Connecticut. The stories I’ve heard about those places—didn’t you have one nun who was just the worst nightmare?

INDIANA: Sister Mary Jude, who should’ve been a truck driver in some real redneck town. She loved to beat kids up, with this thick triangular ruler, right across the hand.

DERN: I don’t know how people parent in this day and age, just before I came here I read an article in a doctor’s office about Raymond Buckley in Los Angeles magazine. It was so frightening what he felt was appropriate when dealing with preschool kids. I don’t know what the whole story is there.

INDIANA: No one does. After reading articles by Dorothy Rabinowitz in Harper’s and by Debbie Nathan in The Village Voice, I’d almost become convinced that these preschool molestation cases were being fueled by antifeminist hysteria. And they probably are, but when I got out here, I saw people I worked with at Legal Aid in Watts 15 years ago, some of whom worked on the McMartin preschool case, and they said it’s all true. Even the animal mutilations.

DERN: It’s terrifying that it occurred, if it did, but it’s caused a real shift in awareness. People are more willing to talk about child abuse. When this whole McMartin thing went down, I was at a dinner party with about eight people, all from different backgrounds and from all over the world. And every single person at that table had had some weird experience as a child. I think everyone has—whether it was with a babysitter, or playing doctor, but usually when some older person tries to come in contact with you. It’s amazing how much we block out. Obviously, the urge to molest children comes from some experience the person has had as a child, and he or she never worked it out. Watching Raymond Buckey describe how he loved working with the kids, I could sense this 11-year-old who’d stopped and never grown further on a sexual level. He denied that anything happened, but even the way he described loving to play with the kids and the toys and so on, it was…weird. It’s a strange world, as David Lynch would say.

INDIANA: But don’t you think it’s weird that when society unearths something that’s been repressed for a long time, suddenly everyone’s pointing the finger at everyone else instead of figuring out how to deal systemically with it? Last night on the news, they gave figures for child-beating in America, something like two million children every year.

DERN: It’s so frightening. Even if you’ve gone through an average childhood, you have girlfriends who get pregnant and then have to choose whether or not to have a child. And this stuff certainly makes you think about what you’re taking on. I mean, I certainly want to have children, but I could never do it until I felt I loved myself enough, and wanted to bring someone into the world because I had some kind of security. I’m starting to, but I still have a lot to learn. I just have two cats, and when I’m in a bad mood—you know, it would be very easy to throw a cat across a room.

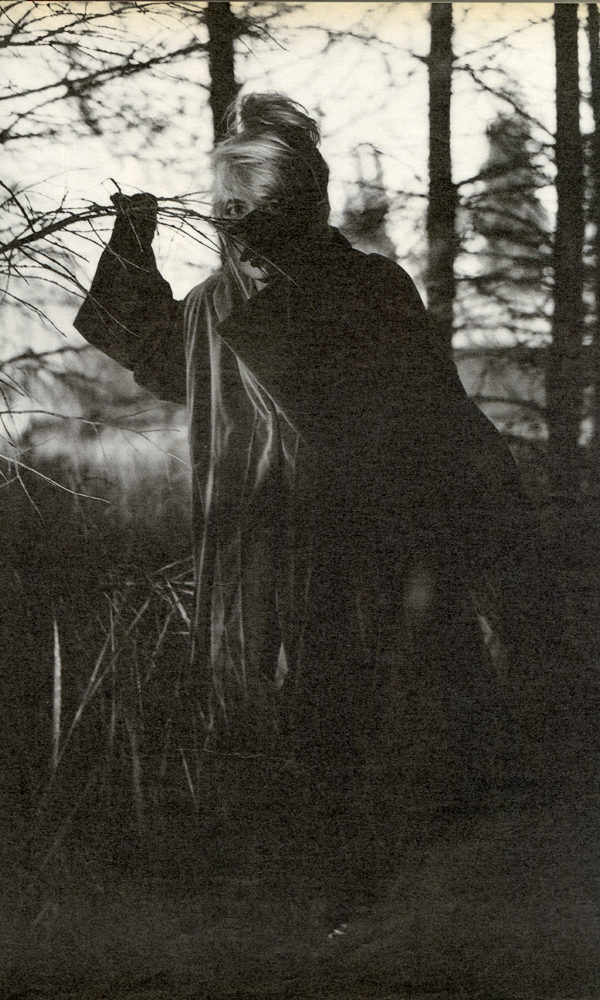

Green velvet petal coat, striped stretch pants, mirrored gloves, and patent leather boots by Romeo Gigli. Vermil Kite Earrings by Mario Salvucci for Fragments.

INDIANA: Years ago I was living with somebody and I kept telling him, “I want a dog, I want a dog.” And he said, “The first thing you’d do, if you got really hysterical, you’d throw that dog right out the window.” And I realized it could very well be true. You just don’t know what you’d do.

DERN: The thing I love about acting is, whatever character you play, it gives you the chance to expose another side of yourself that maybe you’ve never felt comfortable with, or never knew about. Not that every character is you, but there are underlying emotions that everybody has. I feel that movies are gifts that come to you, and there are no accidents in what you end up doing. I study Jung, who talks a lot about the shadow side, the repressed side. I think the scariest thing in the world is repression. There’s plenty to be idealistic about, but we have to be aware of all sides of ourselves, and there are definitely shadows in all of us.

INDIANA: How do you find what you need to work on in a part? I’m thinking of Connie in Smooth talk and that mind-boggling scene where you’re inside the house and Treat Williams is outside talking to you through the screen door, and it’s really Connie’s passage from childhood to being a woman.

DERN: It’s funny you bring up that scene, because there’s a similar scene between myself and Bobby Peru, Willem Dafoe’s character, in Wild at Heart. In Cannes, people kept comparing those two scenes and asking why I’m always half-seduced and half-raped in my movies. I’m sure I don’t know. But whether a movie part comes to me or I seek it out, there’s always this journey to darkness through light, or vice versa; that element has been in almost everything I’ve done. In Smooth Talk it was a much more intuitive search—I was only 17 at the time, and I wasn’t aware, as women are when they get a little older, that there’s always a side of a woman that likes a man from the other side of the tracks. We all have an attraction to what’s different from us. Connie and Lula and I all share something, namely that we all want to be loved or accepted in a love relationship or family relationship, whatever; but we all bring our baggage with us in terms of how we expect that love. Connie has such a need to be found attractive by a grown-up man, and there’s that feeling of wanting to break away from mother and say, “I’m a woman now.” A couple of years before I made that film, I certainly had a lot of those feelings. My transition was much calmer, but I tried to use those dynamics in making the character.

Wild at Heart made a few people angry—they thought I was exploiting women by showing that when a woman says no she really means yes—that Lula’s repulsed by Bobby Peru, yet she wants him. I don’t feel that way at all. In Wild at Heart I tried to find the essence of myself and Lula, what we shared; so the scenes with Bobby Peru became even more intense and connected. I had dreams the night before I did that scene which revealed why the character does what she does. The more conscious I become about these different sides of myself, the more I can contact each side of the character.

INDIANA: Those scenes also seem connected by the fact that the audience projects onto them a greater physical threat than is actually there.

DERN: It’s amazing, too, how many people said after seeing Smooth Talk, “Well, obviously he raped her.” I think he actually did just take her for a drive. I also think both Lula and Connie are in control in those scenes. The line I find fascinating in Smooth Talk—when I come out through the screen door and Treat says, “Come on, you gonna come out of your daddy’s house, my sweet blue-eyed girl?”—is when I reply, “What if my eyes were brown?” It’s sort of “fuck you,” in a way. It’s like Connie’s saying, “I’m in control of this, I’m in the driver’s seat.” Maybe she says it out of fear, to protect herself, but on some level she is controlling it.

INDIANA: In Wild at Heart, though, doesn’t Bobby Peru force Lula to say, “I want you to fuck me”?

DERN: Well, with Lula, some people will say, “My God, he raped her.” But the bottom line is, she never touches him. And Lula has an orgasm. She wins! She gets off, and he gets nothing. What’s devastating to her is that he thinks he’s won her, so she’s afraid for her boyfriend, Sailor. She gives Bobby Peru what he wants on the verbal level, saying what he wants her to say, out of general fear. But at the same time, she stays in control. It’s a battle, that scene.

INDIANA: You were fantastic as the blind girl in Mask. I was completely convinced by you, even in the scene where Eric Stoltz gives you different things that are hot and cold, to explain what colors are—it could easily have turned into saccharine, but it really worked.

DERN: Thank you! I think it’s interesting that there’s always a dark cloud hanging over my character, in every movie. Even in Fat Man and Little Boy, where it’s a real dark cloud. In Mask, it’s more the judgment of others, but it’s still a threat. Sandy in Blue Velvet is the archetype of that. David Lynch says, “If you wanted to buy a bottle of innocence as a shampoo, you’d buy Sandy in Blue Velvet.” Lula, I guess, is a bottle of passion-flavored bubble gum.

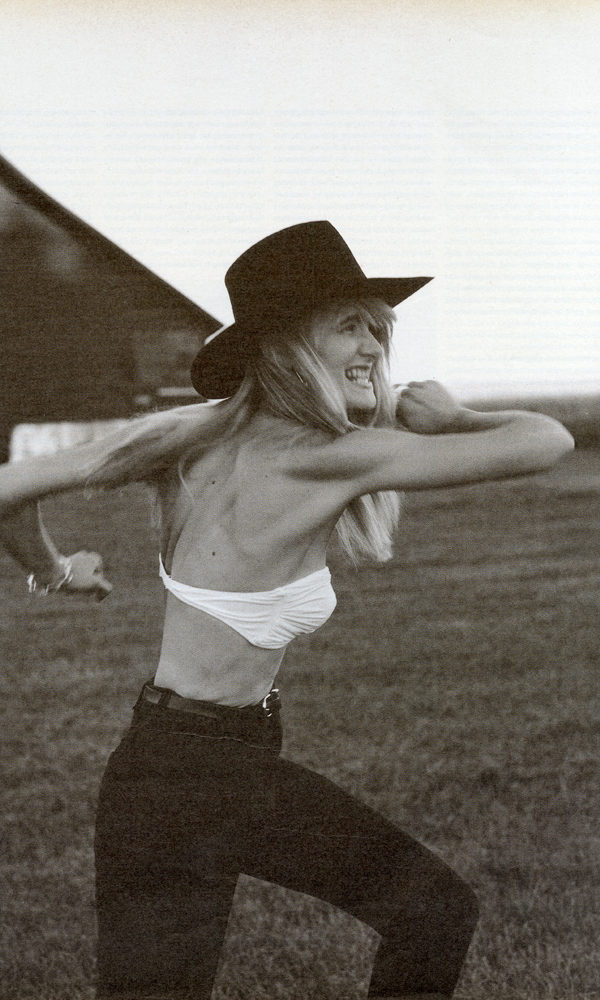

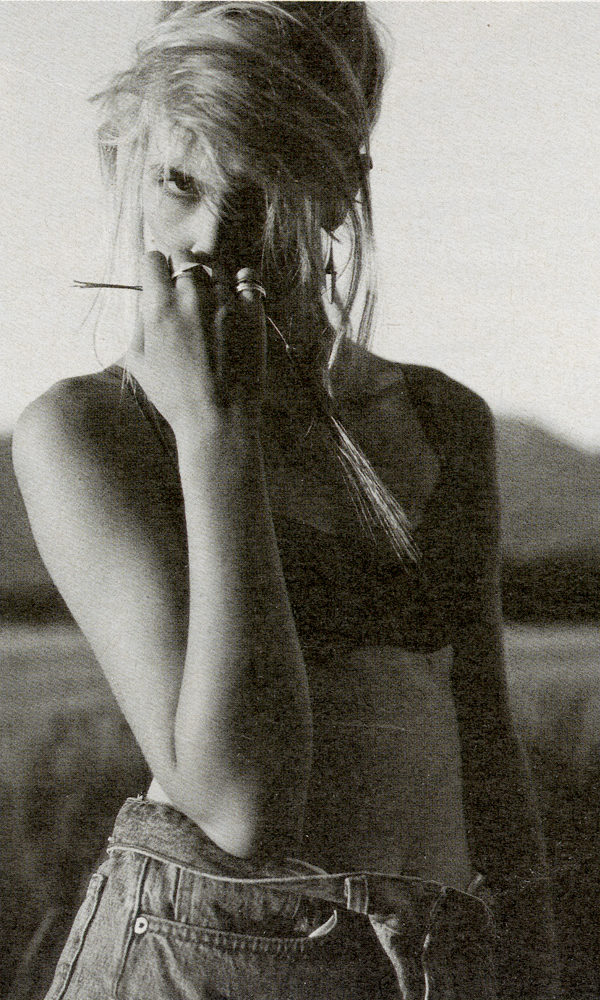

White top by Norma Kamali. Black jeans by The Gap. Sterling link bracelet and sterling quartz crystal earrings by Mario Salvucci for Fragments.

INDIANA: You always play characters embedded in difficult family relationships. In Wild at Heart it’s this demented mother; in Mask you have these disapproving parents. Did some of those parts come to you because you started acting so young, or are you naturally attracted to them?

DERN: Maybe it’s some kind of karma. I certainly don’t seek that out. In fact, I hadn’t really thought about that, but you’re right. I’m very connected to my own family, and maybe I like to explore the feelings that come up in families. I’m fortunate that my parents taught me to look further into why I might feel a certain way; it was normal to expose things. When I started dating I had relationships with people who came from families that weren’t at all artistic or whatever, and they didn’t understand how to communicate. I find that so boring.

INDIANA: What do you think the difference is between the way you went into acting, as opposed to someone who didn’t have it in their background? You came into it from inside rather than outside.

DERN: I never had a misunderstanding of what it was about. Unfortunately, overall, movies are a conglomerate. People buy and sell people in this business, which can get really ugly unless you have the right set of values and understand why you’re doing it. Luckily, I was raised by people who’d already gotten to that point, and seen all the yuck stuff—which is probably why they originally didn’t want me to act. I also understood the difference between getting a part at a Hollywood party and really getting a job. I knew you had to go in and audition and maybe then they’d hire you, and that’s where you start. I also had a good understating about press: that it’s the actor’s responsibility to publicize his or her films, that the press can be fun, that it’s not about hyping yourself into stardom or trying to sell yourself as a hot ticket. I think a lot of young actors now are getting caught up in that. And it’s very easy to get caught up in. there’s a hype going on now that I haven’t seen in years, and it’s actually more about press than it is about an actor’s work or what films they’ve been in.

INDIANA: You were always aware of what your parents did for a living?

DERN: Right after I was born my parents were doing a television show called Castle Keep. It was one that Robert Altman had written. I’ve been talking to him about doing a movie, and he told me he remembered me when I came to the set in a drawer, which is what my parents used as a crib—a drawer from their motel room. It was like right from the hospital onto the set.

INDIANA: In Wild at Heart, it’s quite uncanny to see you and your mother playing daughter and mother. The resemblance is extraordinary.

DERN: I think it’s a little frightening, given the characters. It’s always been a desire of mine to work with my parents, so this was a wish come true. The first day we did a scene together I came down the stairs and my mom pointed that finger at me: “Don’t you dare talk to that boy again!” You know, I’ve seen that finger for 23 years. And I started laughing, she started laughing, then the whole crew broke up—in that moment, they all knew that she and I had been there before. On the third day of shooting, I saw her getting made up. She was certainly in her glory, because she’d done the bathroom scene, she had such a wild outfit on, she was having eyeliner put on, and Nick Cage came up behind me and whispered, “Look over there, that’s your mom.” It’s comfortable to be on a set with her—I’m used to that, but she blew my mind when I saw the movie. We were in so many scenes separate from each other, neither of us knew what the other was doing.

INDIANA: She’s bigger than life in Wild at Heart.

DERN: Every little thing she did—her nails, her different wigs. David and I had lunch the day after she finished shooting, and I asked him how her last scene went, and he said, “Who would have thought your mother would turn out to be the ultimate David Lynch actor?” At one point she was supposed to be watching my abortion, in that flashback where I’m on the table. David said, “We’ve got to do something different, Diane. We need something there.” And mom got a lollipop and starting waving it in my face, like, “Honey, if you’re good you’ll get al lollipop.” In the middle of an abortion, your mother offers you a lollipop? She came up with weirder ideas than I would have. Obviously, we’re lucky we have a good, healthy relationship—my god, can you imagine if that really was our relationship, trying to work with that person?

INDIANA: But was it sort of a nightmare recasting of your relationship?

DERN: Actually, not at all. You know, ther was a television show called The Innocents of Hollywood. Brooke Shields is a friend of mine and she saw one of the introductions to it, and she called me and said, “I think you better check this out.” And on this show they talked about parents who’d ripped off their kids. One of them said, “My mother stole $300,000 from me as a child.” Well, my mother opened a bank account for me when I made $60 on my first day of work as an extra. She’s that kind of mother. But god knows what people will say when this movie comes out. It sounds like a cliché, but she’s really one of my closest friends, and so’s my dad. He and I weren’t very close when I was younger, but now we’re best friends. I do think my mother was a bit overprotective, not in any sordid way, but just normally. She certainly might say to me, “You know, Laura, I don’t have a good feeling about that guy. I don’t know if I want you to go out with him.” But if you’re asking, “Would she try to fuck him in the bathroom and then hire a hit man to kill him?”—I think that’s a little further than she’d ever go. It’s interesting to talk to my mom about her character, because she sees her as a mother who’s just trying to protect her baby from a bad boy. I think that’s why it works so beautifully—she has conviction about what she’s doing.

White top by Norma Kamali. Black jeans by The Gap. Sterling link bracelet and sterling quartz crystal earrings by Mario Salvucci for Fragments.

INDIANA: I read the Barry Gifford novel Wild at Heart the other day, and in the book that’s actually how the character comes across—she’s kind of slipped a gear, but that’s her basic motivation.

DERN: The rest, obviously, was all David, but the book is quite beautiful, because the characters of Sailor and Lula are completely there. They’re my favorite characters, ever. There’s something so accessible about heroes who have faults.

INDIANA: It’s also one of the few Hollywood movies that depict a sexual relationship that isn’t infantilized.

DERN: From the beginning, Nicolas and I had long talks about that. These are two people who turn each other on because they love each other. There’s never a moment where one tries to turn the other on by making the other jealous. One of my favorite scenes is where he tells me about his first sexual experience. It’s so great, because Lula lets herself get turned on by it. When I first tried to figure out who Lula was, I looked at that scene. In it he’s talking about having sex with this chick, and it was so hot, and she says, “Did she have brown hair?” And when I saw that line, I immediately thought, “She’s pissed, she’s saying, ‘Oh, a brunette, and was she better than me?'” But then I realized the key to Lula is, she thinks she’s got the hottest little body in the universe, that her baby loves her, and she just loves her boobs, she loves her ass, she just loves doing her stuff, and she’s a truly secure person in that whole area. And she’s such a bubblehead, in a way, that in the middle of that conversation she just wants to picture the other girl better. She wants to know what color her hair was. Then the fact that Sailor would pick up any note of insecurity and comeback with, “but gentlemen prefer blondes”—it’s so beautiful, they’re just madly in love. When have you seen that in a movie? Especially with a young couple. Usually there has to be some climax scene where one cheats on the other in some brutal way and says, “I don’t love you anymore,” and the maybe they get back together in the end.

White top by Norma Kamali. Black jeans by The Gap. Sterling link bracelet and sterling quartz crystal earrings by Mario Salvucci for Fragments.

INDIANA: The sexual frankness never turns into some kind of hypocrisy. Sometimes in a film you see two women talking about sex but you never see a man and a woman discussing it as if it wasn’t a totally traumatic, overwrought, manipulative activity.

DERN: The actors are telling the truth on some level, and people have to believe it. At Cannes, a lot of people said, “Oh, shocking,” but this Italian girl said to me, “My god, I just said that to my boyfriend the other night.” That’s what Lula talks about. That’s life—to turn each other on, to feel good, to feel in love. I’d never done nudity in a movie; I’ve never sort of condoned it for myself, but David wanted it, and I was completely comfortable with it because that love story was so protected. There’s never a moment where you feel anything is exploited. I’m interested to see what the American reviewers talk about compared to the Europeans, who really didn’t question it much.

INDIANA: Well, especially lately, anything that deals with the body or with sexuality gets talked about in terms of obscenity, even things that everybody does—everybody who has any kind of life, anyway.

DERN: There are people on the ratings board and so forth who don’t want certain scenes in the film.

INDIANA: See, I find that shocking.

DERN: It is! There are people who come up and say, “What graphic love scenes. I think, How can a love scene be graphic? Have you seen Total Recall? In this R-rated movie you see a man who you’ve seen being in love with and sleeping with this fabulous woman shoot her right through the head. “Consider this a divorce” is supposed to be the funniest line in the movie. And Nick and I can’t make love? That’s scary. And our hero? Arnold Schwarzenegger? Using a body as a shield against bullets? Hey—the world’s a big place, and people get away with what they get away with, but to attack David for doing things I’ve seen in many movies, that’s weird.

INDIANA: The Los Angeles Times had an article discussing the fact that a director like Irvin Kershner has to make a movie like RoboCop 2 just to get work.

DERN: I saw the RoboCop 2 trailer last night, and when I saw he’d directed it I couldn’t even believe it. Irvin Kershner, no matter what anyone says, has done some great work. Eyes of Laura Mars is an incredible movie. And he did some beautiful little films in the early ’70s.

INDIANA: The Luck of Gingery Coffey, I think, and some other very sensitive movies. But the Times says directors who won’t make these techno-splatter films can’t get work. Only the day before, The New York Times gave statistics on homicides of young men worldwide; the rate in the U.S. was 22 percent, with the next highest rate something like five percent. When they correlated that with the methods used, it was something like 75 percent death by handguns in the U.S. Sometimes violence in a movie makes sense—Internal Affairs, for example—but Total Recall is just wall-to-wall ketchup.

DERN: I’m friends with Renny Harlan, who directed Die Hard 2, and I will say, I thought it was beautifully done. What I loved about it was that the bad guys are basically American political figures. They don’t have East German accents or whatever. It’s interesting that the same kind of movie, with the blood and everything, can be done well. Unfortunately, that’s what brings in that age group that wants to see those movies—but there’s certainly a line to be drawn somewhere.

INDIANA: How many scripts do you look at in a given week or month?

DERN: It’s always different. If you have a movie coming out and people are talking about you, the amount of scripts will build. It also depends how in sync my agent and I are at that moment. Sometimes she’s automatically say, “This isn’t right for you,” and I can trust that she’s right. I look at everything anyway, but I don’t know the numbers. Right now I’m seeing a lot of scripts. It varies.

INDIANA: What percentage of the ones you see contain good parts for women?

DERN: Few. Very, very few. What I consider a good part for a woman and what some other Hollywood people think are good women’s parts are very different. I don’t’ want to play the supportive girlfriend who has nine scenes and just loves that man, maybe cheats on him in one scene but will always be there, and I mean—give me a break. You’ll be offered the “lead” in this new hot film with such-and-such A-list director, “a fabulous part”—a fabulous part? A fabulous part is a character with a soul, who starts here and goes to there, you know? There aren’t many of those. I’m lucky enough that directors sometimes seek me out for little projects that people don’t even know about, that just surface later on.

I made a commitment to myself: that I wanted to be an actress, and I wanted to do films that make a difference. Whether it makes someone laugh, or it has a moral to the story—it doesn’t have to be an ethical film, but it has to move people. If it doesn’t excite me, it’s not worth doing—it’s better to work on myself and my own life and wait until another great thing comes along. I don’t turn my nose up at anything. If it’s a great part, it’s a great part. It’s not like, “I don’t make studio films; I work for David Lynch and maybe a few American Playhouse directors, but that’s it”—I’d love to do a box-office hit.

INDIANA: But most box-office films getting made are male-buddy movies, aren’t they?

DERN: Exactly. Look, if somebody said tomorrow, “We’re making a Lethal Weapon formula movie, but it’s incredibly well-written and for two women,” I’m not going to say, “Oh, forget it, it’s formula.” I got an idea the other day, that somebody should write a typical formula movie, a Lethal Weapon, and make it with me and my dad. It could be all father-and-daughter capers. But I’d want someone really weird to direct it. I love comedy. David’s the only person I’ve worked with more than once who sees me as a specific thing—he sees me as the sexy bimbo, in ways, and he also sees me as Lucille Ball. Actually, Nick and I did Lucy and Ricky in two scenes that were cut because the movie was four hours long.

INDIANA: People don’t make comedies anymore, either.

DERN: Not the ones I like. If I could do The Philadelphia Story or The Lady Eve—where are George Cukor, Preston Sturges, and Howard Hawks today? Those are my favorite movies.

INDIANA: Bringing Up Baby.

DERN: And Mr. Smith Goes to Washington is one of the greatest films of all time. And those character parts—what about good small roles for women? I’ve told my agent, if there are two great scenes in a film, I don’t care, if it’s something with that great edge to it. Like, Virginia Mayo had kind of a small role in The Best Years of Our Lives, but you got the whole character in one scene. Where are those parts? I was talking to somebody about great actors: Morgan Freeman’s name came up, Forest Whitaker, Denzel Washington. And I realized, there’re no black actresses. Where’s there a black actress who’s been extremely successful in the past 10 years? And the salaries now—Meryl Streep makes $2 million, Arnold Schwarzenegger makes $15 million.

I don’t care—I don’t care, but I don’t get bitter about anything as long as I can work and do the things I love. And it would be a beautiful world if those things I love and that mean something could remain as they are. I read a script last year that was dark, beautiful, brilliant—and it became a huge fairy-tale success this year, but it’s a completely different movie from anything I read. It’s just shocking what’s created through the process of working with the studio, and what makes money. It would be great to make a movie that had the style of a great ’30s film or a movie of David’s or some other director I love that could also make money, because that would say to the corporation, “Yes, you can make money and still do art.” But it’s tricky.

INDIANA: Are there any great women characters in literature that you’d like to play? I see you in William Faulkner roles.

DERN: Wouldn’t that be beautiful? There re character I love that are such martyrs, and the ones with a comical side to them, Oscar Wilde sorts of characters. But Faulkner or even Fitzgerald—if I were a man, I’d love to play Dick Diver. One character I’m fascinated by, and would love to see done correctly, is Hester Prynne. There’s a lot more to that story than we’ve seen! It has so much to do with AIDS, with any issue—South Africa, anything. It’s about judgment and fear in a puritanical society. That a man would be so afraid that he’d lost control—that’s what it’s about. Hester would be really exciting. Or a movie character like a Mr. Smith Goes to Washington but a woman, someone who’s an innocent and sort of wins over the system. I love people who fight the system.

THIS INTERVIEW ORIGINALLY RAN IN THE SEPTEMBER 1990 ISSUE OF INTERVIEW.

New Again runs every Wednesday. For more, click here.

———

Hair: Eric Gabriel/Oribe

Makeup: Lynn Baron

Production/Location: Main Street Production