GUITARS

Mac DeMarco and Akiko Yano Reunite, 200 Songs Later

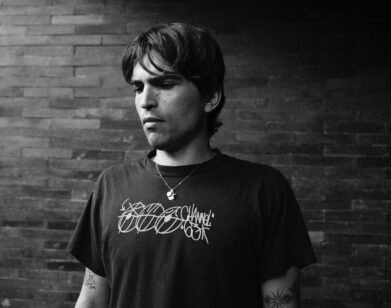

13 years into his career, Mac DeMarco is still looking for answers. From his self-diagnosed “demo-itis” to feeling like he knew more at 22 than at 35 to his almost trance-like ability to make music—he can’t help but wonder why he is the way he is. When she got on a call with the singer-songwriter last week, Japanese jazz musician Akiko Yano attributed DeMarco’s output to god-given talent. “It’s in your head,” she exclaimed. “It’s coming from your brain.”

His curiosities aside, DeMarco is going back to the basics of sound with his sixth studio album, out next Friday. Guitar, as its aptly titled, features 12 stripped-down tracks consisting only of guitar, voice, and the occasional drum, a markedly different approach from some of his better-known synth-saturated albums like Salad Days (2014) and This Old Dog (2017). To mark the occasion, the two friends and sometimes-collaborators discussed the development of the album—what came before it, where it started, and how it ended up feeling like its own little entity within his extensive discography.—CHARLOTTE ZAGER

———

MAC DEMARCO: How are you doing?

AKIKO YANO: I’m doing okay! Thank you for inviting me.

DEMARCO: Absolutely. It’s good to see you.

YANO: Good to see you. I saw your tour dates. It’s amazing.

DEMARCO: It’s going to be good.

YANO: Of course it will be. You scrapped an entire album before starting Guitar. What told you it wasn’t the right record? Is it true?

DEMARCO: I don’t know if it’s scrapped. I recorded maybe 14 songs before the album that you heard. And maybe this happens with you, but I’ll have the demo version and then when I go to make the final version, I like the demo version too much. I call it “demo-itis.” I made those 14 songs and then I was trying to do the final version, but it was like I was trying to just make the demo again. It’s almost like trying to recreate something that is inherently imperfect. It’s a loop and you just go crazy. I’ve done it before and I end up with this finished product where I’m like, “I think this is fine, but I know that I like the other one better.” That’s what was happening. I was going crazy and I was moving the drum mics around and going insane. It was bad. So instead of going insane for longer, I just decided to start fresh. I wasn’t sure if it was going to work, but it worked fine. I also feel like when you haven’t done it in a long time—I haven’t written songs in a while—it almost felt like I had to turn the tap on. Some of the songs were cool, but I felt like I had to get the old water out or something. Maybe someday I’ll release it. It’s like Prince. I’m nothing like Prince, but he had a lot of stuff that he talked about but kept in the vault.

YANO: In the previous year, you told me that you would like to release 200 songs and you said, “I mean it.” What happened with that idea?

DEMARCO: I did it.

YANO: What?

DEMARCO: Did you ever see that? I did it.

YANO: What?!

DEMARCO: Oh, yeah.

YANO: Oh my goodness. It sounds like cooking. You’re baking and then the people are waiting at the table and you say, “Hey, here’s the one that I made. Please eat it right now.”

DEMARCO: I feel like that’s how it is with every musician, no? You don’t think that you’re baking?

YANO: That’s true.

DEMARCO: Maybe I’m just the only chef in my kitchen most of the time. But with the really long one, and even with Five Easy Hot Dogs, those are kind of different from Guitar. It’s like a normal album. 12 songs or something, which is fine. I have respect for the normal album style, but weird is also good. Experimenting with the format is cool. Some of the music that I put out on that long one is pretty strange. But that’s interesting to me. You have a lot of CDs. CDs are cool, right?

YANO: I’m old-school.

DEMARCO: When did CDs come out? In the ‘90s or something like that?

YANO: The ‘80s.

DEMARCO: Late ‘80s maybe? When did it go from cassette to CD?

YANO: Maybe early ‘80s, because my daughter was playing with the cassette when she was a baby.

DEMARCO: When CDs came out, they made the audio standard. Some people still use CDs, but now most people use Spotify or the internet or whatever. But we’re still on the CD standard of audio? It ain’t right. We had to put the long thing on a Blu-ray disc because it was the only thing that could take that much. But with the new album, it’s just a new album.

YANO: It sounds like you released this big album and it was a stepping stone. Now you can go into the normal album.

DEMARCO: The one that I recorded before Guitar, it was almost like a flush or like clearing your plate. Maybe you feel that way sometimes? With the big one that I had, there were a lot of songs that I liked a lot but I had recorded years ago. I was like, “Maybe I could rerecord them and put them on an album?” But I’ll just end up liking the first version more. It was a way of being like, “I can just put these out, then they’re out.” Do you get that at all, or are you always fine to rerecord?

YANO: If I want to rerecord, I do.

DEMARCO: But have you ever been in this situation where it’s like, “I just can’t get it to sound like the demo version or something like that?”

YANO: A couple times, yes. And that time, I rerecorded it. So it’s making a different version, close to the demo version.

DEMARCO: See, it’s a problem that I have. It’s almost like a purity thing. It’s like the first time it gets recorded—

YANO: You remember that moment.

DEMARCO: Yeah, it’s when it was born. It’s tough for me, but the difference too is that you’re an amazing musician and you could probably expand on something musically. I think that when I record something, I get lucky sometimes. I’m like, “Okay, that’s good! How am I going to do that again?”

YANO: I noticed this album, Guitar, 12 songs in there.

DEMARCO: I think 12, yeah.

YANO: Only one song, the last song, “Rooster,” had an intro.

DEMARCO: This is true.

YANO: You have something in your heart or body that you’d like to let out at that moment. You don’t need any intros or a very complicated outro or a more fancy format for the song. You just need this gem of the musicality.

DEMARCO: Yeah, that’s part of it. The whole album, I feel like it’s just a nice little package. I’m satisfied with it. You know what? I’ve been saying this anecdote a lot. You remember the first time I came and met you in New York and you were listening to the Here Comes the Cowboy record? And you sat down at the piano and you were like, “This is the major scale.” Then you were like, “This is how I hear the major scale.” I wonder if with this album you think it’s still my kind of sense of harmony. Has my scale changed at all? Or do you think my scale is my scale?

YANO: Your scale is your scale but you are advanced. The way you approach the sound and the song itself is more condensed. And that’s the thing that I realized was different from the previous records. You are grown up.

DEMARCO: Rock and roll grown up. I love it.

YANO: Maybe a lot of people ask you this question, but why did you name the album Guitar?

DEMARCO: When I finished, I listened to it. The first song, “Shining,” had a keyboard on it. But then I realized none of the other songs had keyboard. So I went back to “Shining” and I deleted the keyboard. And then I went, “Well, now I can call it Guitar.” I think Guitar is a good name for an album.

YANO: Guitar is your first instrument?

DEMARCO: Yeah, it’s the only one I can play. It’s funny because I go in with guitar and I go out with guitar. Sometimes I’m like, “Ugh, guitar, I don’t know about guitars.” But then right now I’m like, “Guitars are cool!” I think guitars are great. I respect it as an instrument. It’s a very low bar of entry. It’s a very working class instrument. A lot of people can play a little bit of guitar. Piano is the same, but I feel like guitar is—

YANO: Very handy.

DEMARCO: It’s very handy. But yeah, it’s literally just that I deleted the keyboard.

YANO: That reminds me. The band Queen? One of the records said, “There are no synthesizers in this record.”

DEMARCO: Should have called that record Guitar [Laughs]. Not that I have anything against synthesizers or pianos. It’s like I picked a couple colors of paint and just kept them the whole time. It’s like when you and I record, too. Let’s go choose one keyboard and we’ll use the Minimoog or whatever. The interesting part to me nowadays is less about a lot of sounds and just about what the song can do. Not that the songs are crazy complicated or anything, but that was the thing—I only had a couple different paints.

YANO: It’s totally designated to guitar. Do you think you would have made this record if you hadn’t moved back to L.A.?

DEMARCO: You know what? I’ve been thinking about this, too. I don’t know if anybody ever asked you this when you moved to New York, for example, where people were like, “Is this your New York record?” I think that it takes longer for a place to seep into your creativity or your music or life. You don’t just go and it happens. But now, definitely. I’ve lived there for eight years and it’s a really weird place.

YANO: Really?

DEMARCO: You don’t think it’s weird? It’s pretty weird.

YANO: L.A.?

DEMARCO: Yeah.

YANO: To me, it’s like California.

DEMARCO: It’s great. The sun is always shining. It’s like a David Lynch movie where it can be beautiful and fun, but then there’s also a lot of dark things that happen there, too. But even when it’s dark, the sun is still always shining which gives it that kind of David Lynch feeling. It’s got its own flavor of surreal. I think also just being around so much of the music industry, I feel even more surrounded by it in L.A. than I did in New York. I think this record pushes back on it a little bit.

YANO: When I made music with you in your place, I felt differently than I did in New York. How did the experience of mixing the album in Canada after recording in L.A. shape the final sound?

DEMARCO: I don’t know if it really shaped the sound that much. I didn’t do that much mixing, per se, but here’s what was really nice. The next day after I finished it, we left. My mom lives in a new place in Canada and I was going to fix it up for her a little bit. That was the priority. And initially, I had this kid Nathan, and he was going to mix the record. And he did, and it sounded great, but in the end, I needed to do it, just because I’m kind of crazy. I’m sure my mixes don’t even come close to his. Even when he was mixing it or when I mixed it, I got to have the record just for me and Kira. I didn’t show it to anybody else for maybe four months until I finally had it done. And then I sent it to mastering. And then I told the people that I work with, “Hey, I have a record.” And they were like, “Oh.” Once you enter it into the music industry machine, it gives it a different flavor.

YANO: It sounds like you produced your own kid, right?

DEMARCO: Exactly. That’s how I feel. I haven’t had a kid yet, so I don’t know how similar it will be.

YANO: To me, it’s understandable.

DEMARCO: It’s tricky. I’m part of the music industry, we both are. It’s a necessary thing. And I’m lucky I get to do it in a way that is not that intrusive, but it’s nice to keep things sacred for a little while.

YANO: I noticed while I was working with you, making music and just picking up some chords and some melody looks much easier than making lyrics.

DEMARCO: It depends on how it goes. I don’t really understand it. I just know how to do what I do. When I finish a song, it almost feels like a miracle. Like how? Where? Where did that come from? How did I do this? And when you’re in it, you’re kind of in a trance or something. It’s exciting.

YANO: But it’s in your head. It’s coming from your brain.

DEMARCO: Maybe it’s floating by—who knows?

YANO: The things you’ve created were coming from your thinking and your history, your childhood memory, and your loved ones.

DEMARCO: Not from outer space?

YANO: No!

DEMARCO: I’d like to think that it all comes from me and from my experience but sometimes I’m just like, “What?” I mean, it’s great. The fact that I was able to make an album in that short period of time and now I get to go on tour again, I’m so pleased. Sometimes I just don’t believe it.

YANO: What are you afraid of losing as you get older and what are you looking forward to?

DEMARCO: There’s a lot of things in my life that I have lost in the last maybe five years or so. But usually when you say you lose something, it’s a bad thing. I don’t eat nasty food as much. I don’t drink alcohol anymore. Well, not really too bummed out about losing that one. I’ve lost cigarettes, and that’s okay. I’m trying so hard to live more presently as time goes on. I think that my conception of what I find beautiful is changing. I don’t really care about being in cities that much anymore. I want the nature kind of thing, and family is becoming more important to me, and good friends. Maybe it’s because in my twenties I was kind of like, “Let’s go crazy, we’ll go on tour forever!” Even though I’m trying to be in the moment and be like, “Look at the mountain. The mountain is beautiful. There is the sun sitting behind the mountain.” I keep finding myself feeling like I don’t have enough time to look at the mountain. I want more time to look at the mountain.

YANO: Yeah. It’s not just getting old—it’s maturity.

DEMARCO: Exactly. I’m not really afraid. You kind of just wake up more every year, and that’s what’s cool about it. When I was 22, I thought I knew everything. But you get older and every year you realize you know less and less and less about everything.

YANO: But it’s a good thing.

DEMARCO: Absolutely.