MASTER

“Humans Can Be Very Depressing”: David Cronenberg, by Jim Jarmusch

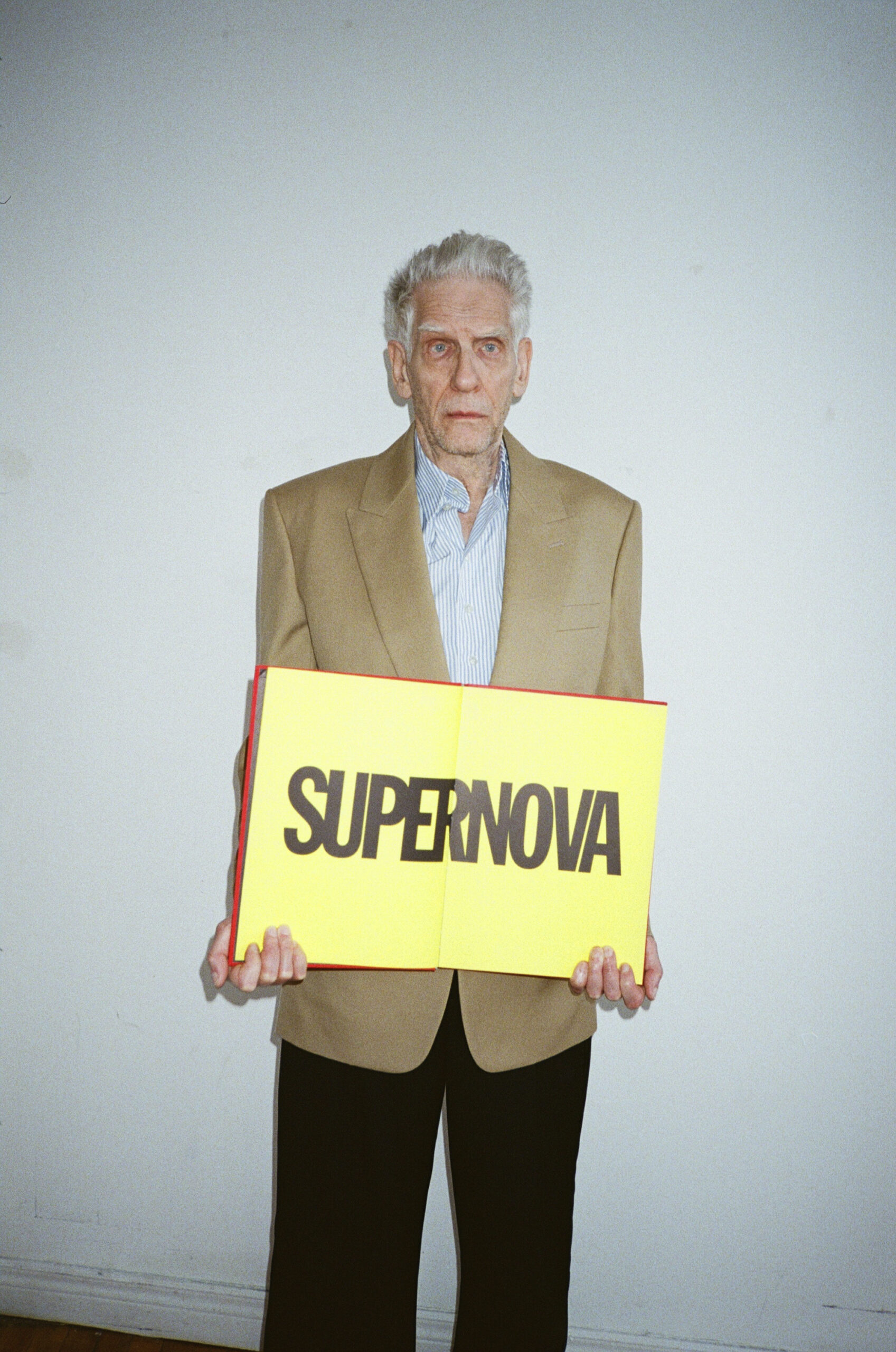

David Cronenberg wears Jacket, Shirt, and Pants Saint Laurent by Anthony Vaccarello.

Minutes before David Cronenberg logged onto Zoom with Jim Jarmusch this past January, news broke—David Lynch had died. The loss of a friend and fellow auteur cast a shadow over their conversation, a stark reminder of mortality, legacy, and the fragile line between life and death. It was an oddly fitting backdrop for Cronenberg, an artist who has spent his career exploring the darkest corners of the human psyche, where flesh, mind, and technology collide. Cronenberg has long been a prophet of our tech-fueled nightmares, and now, at 82, his legacy continues with The Shrouds, a thriller about an app that lets mourners watch their loved ones decompose. Is he a visionary or just a sharp observer? Will tech save or destroy us? And does indie film still stand a chance? Over the course of their conversation, Cronenberg and Jarmusch do their best to find out.

———

WEDNESDAY 2 PM JAN. 15, 2025 TORONTO

JIM JARMUSCH: Hello?

DAVID CRONENBERG: Hi Jim. We can’t see you.

JARMUSCH: I don’t know how to do that.

CRONENBERG: Well, there’s a video thing with a slash through it and you just hit it with your—

JARMUSCH: Okay. Can you see me? You’d probably rather not.

CRONENBERG: I’m very happy to see you. Listen, I just heard that David Lynch is dead.

JARMUSCH: I just heard that five minutes ago. Really a shock. I don’t know what to say. I’m kind of reeling from it.

CRONENBERG: Yeah, me too.

JARMUSCH: What a strange, beautiful gift to cinema and expression in general. I thought the 18-hour version of the reboot [Twin Peaks: The Return] was one of the best things I’d seen in a number of years.

CRONENBERG: Yes. It was pretty hypnotic.

JARMUSCH: Yes.

CRONENBERG: I was flirting with doing a Netflix series, and I was interested to hear how exhausting and crushing it was for him to do. I think it was 18 episodes and he wrote and directed them all. That’s incredible. That’s beyond what we do in movies.

JARMUSCH: What’s even more perplexing to me is he wasn’t able to get his movies financed. But on the basis of Twin Peaks, they supported him in making the 18 episodes. It’s really an 18-hour film in a way.

CRONENBERG: It totally is, yeah.

JARMUSCH: But still, he couldn’t get financing just to make a feature film.

CRONENBERG: Well, I know that you’ve made comments about the film industry being dead. Did you ever think you were really a part of the film industry?

JARMUSCH: No, not really. I consider myself happily marginal.

CRONENBERG: Me too. And David as well. I knew him when he was doing Dune for Dino De Laurentiis, because I was doing The Dead Zone for Dino. So I was in L.A. a lot, and I remember going to Bob’s Big Boy burgers and having lunch with David and talking about all of that. He was already in trouble with Dune. He really liked De Laurentiis, as did I, but he said, “He’s no help.” I think he was being muscled by the studios. And I think the film was cut separate from him.

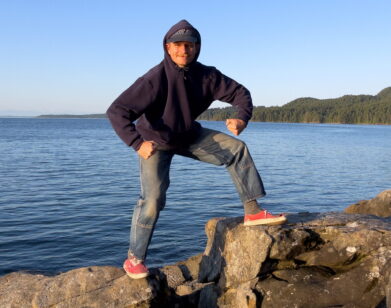

Sweater, Shirt, and Pants Prada.

JARMUSCH: I only met David a couple times—once in an elevator in Cannes at the Carlton Hotel.

CRONENBERG: That’s a classic.

JARMUSCH: He gave me a CD of some trumpet music he had produced, oddly. Then I met him a couple other times. I tried to induce him into making an electric guitar collaboration because he plays very unusual electric guitar stuff, as do I. But he said, “Well, let’s think about that and keep in touch.” It never happened, but I have a great Dino De Laurentiis story. He called me into his office when I was very young, after my second film, Down by Law, and said, “Why do you make amateur films instead of professional films?” And I said, “Can you tell me the difference?” This was in the mid-’80s. He said, “Yes, professional films cost at least $5 million.”

CRONENBERG: [Laughs] He’s right about that in some ways. I started off doing films inspired by the New York underground. I shot them myself, cut them, edited them, and all of that. But when I decided to write a script that might be commercial, I thought, “I have to make money somehow, which means that the film actually has to have a certain budget, and I have to get paid as a writer-director.” That’s when I first realized that I was going to be part of the film industry—even though Canadian filmmaking was, by its nature, independent filmmaking. Certainly independent of Hollywood.

JARMUSCH: I have so many things I want to talk to you about. I know you started with the Toronto Film Co-op, which was underground films more or less, and you were inspired by a friend and mentor of mine, Jonas Mekas.

CRONENBERG: Yes, that’s right. I was at some distance, being in Toronto, but there were times when New York underground filmmakers like [Ed] Emshwiller and the Kuchar Brothers would come to Toronto. There was a theater that had been built into what used to be a post office, called Cinecity. They would do 24 hours of underground films. You’d come out in the morning and have coffee, and then go back in and watch some more. American filmmakers came up to Toronto; it was very inspiring.

JARMUSCH: Wow. The Kuchar Brothers were masters of great titles like Hold Me While I’m Naked.

CRONENBERG: They were so funny. Partly because they were doing parodies of Hollywood stuff, but also because of their unique sensibility. It was the same with Ed Emschwiller’s masterpiece, a really short film called Relativity. Hollywood, of course, was not remotely interested in anything like that. In fact, even the European films, which were also an influence for me, weren’t doing what the underground filmmakers were doing.

JARMUSCH: I grew up in Akron, and as a teenager, we would go to this adult movie theater that would show these Underground Cinema 12 programs. I don’t even know if we had our driver’s licenses. It was just stoners going to see these underground films, but in Akron, it was a big revelation to see things like Chelsea Girls. You may not remember, but I got to have lunch with you some years ago in Cannes on the beach. I just remember laughing a lot and finding you very funny. Your reputation from your films is very dark, but I don’t have that same impression. I have to confess, part of me considers your work comedic.

CRONENBERG: I totally agree with you.

JARMUSCH: I find very funny things in your films. At times, it’s been embarrassing to me in a way, because I’ve been in movie theaters watching your films, laughing out loud, and having people look at me like I’m some kind of sicko. “You think that’s funny? They open a wound and try to fuck it.” [Laughs] So I have to salute you as a semi-comedic filmmaker.

CRONENBERG: I recently met Woody Allen in Paris, and he felt very familiar to me, let’s put it that way. One of the things I say about my new movie, The Shrouds, which is technically a very dark and disturbing movie, is that it’s also very funny. It’s a strange audience at Cannes, as you know. There’s a mixture of local people and producers and distributors. But it’s also a language thing. It wasn’t until it was shown in Toronto and New York that I thought, okay, at least now the audiences really get the humor.

JARMUSCH: Weaving grief with comedy and science—it’s an unusual film, for sure. These days, financing our films has become the worst nightmare. I know that we both got some help recently from Saint Laurent in Paris. I was wondering how that worked for you? For me, it was really a relief—especially them not being film people telling me what I should do. I always have final cut, but they were appreciative of what I did.

CRONENBERG: I agree. I had a very good experience with Anthony Vaccarello. The Shrouds is a Saint Laurent coproduction with other entities. I think they still have things to learn about film production, but they were totally respectful. At one point they were saying, “Oh no, we want to dress everybody in the film, including the extras.” And I said, “Well, we actually don’t dress the extras. They bring their own clothes because we can’t afford to dress them.” I also don’t think they realize the time pressures. In the film business, if you’re going to dress somebody in a Saint Laurent suit, it doesn’t have to be perfectly made. It has to be perfectly fit, and it has to last for the shoot, but it has to get there fast. I think that the time sequences in the fashion business are quite different from filmmaking. So there were those kinds of anomalies and little stutters. But it was very interesting for me. In fact, in two weeks I’ll be at a Saint Laurent fashion show in Paris, because the Cinémathèque Française is doing a massive retrospective of my stuff. It’s kind of scary. They have everything I’ve ever done, including shorts that I did for the CBC [Canadian Broadcasting Corporation] 50 years ago on two-inch videotape, which was the standard then. As luck would have it, Saint Laurent is doing a fashion show there.

JARMUSCH: I’ll see you there. I’m going also.

CRONENBERG: Oh, you’re going to be there? That’s fantastic.

JARMUSCH: Any excuse to go to Paris, but also I have to do a few things with them, a little documentary.

CRONENBERG: I did like the idea that you and I have become runway models late in life.

Sweater, Shirt, and Pants Prada.

JARMUSCH: [Laughs] Well, my 19-year-old daughter was impressed.

CRONENBERG: That’s important.

JARMUSCH: I had the same experience. I have the wonderful costume designer Catherine George, and I was very specific with Saint Laurent: It’d be great if they made all the clothes, but I’m very particular, and they have to suit the characters, and I’m not taking things as a Saint Laurent commercial, as much as I do respect their designs. Anthony is really a brilliant designer, but it worked out because they said, “Okay, if you need the clothes to be distressed or whatever, we’ll just do that too, or you can do it. Or if you want something in a color we don’t make, or a style that isn’t currently made by us, we will create it.” And they did that for all my characters. You would never know that all the clothes are from Saint Laurent.

CRONENBERG: Fantastic.

JARMUSCH: I know you’re a writer, and you’re interested in certain writers that are very important to me, like Burroughs, and Philip K. Dick, Nabokov, and, of course, J.G. Ballard. I love Crash very much. One reason is the idea of sex being as tied to procreation as control, something that Crash addresses in a very important way. J.G. Ballard is now considered almost prophetic, as is Burroughs, and as are you, in a way.

CRONENBERG: Weirdly.

JARMUSCH: [Laughs]

CRONENBERG: I don’t think of art as prophecy, and I don’t think my purpose in making the art that I do is to be a prophet. But if you are an artist, you perhaps have antennae that are more sensitive than other people’s, or at least you’re paying more attention. There are signals in the zeitgeist that are suggesting what is happening beyond people’s normal comprehension. And so if you’re sensitive to that and you allow that to take control of some of what you’re doing, you’re going to anticipate things that will happen. People especially talk about Videodrome that way, as anticipating the internet and so on. When you see the movie, it’s kind of undeniable.

JARMUSCH: Your interest in science and technology runs through your work. Did you study science?

CRONENBERG: I did a year of organic chemistry at the University of Toronto. I really thought that I could be a writer who was also a scientist, like Isaac Asimov, who was a genuine scientist, legitimate, but also a prolific science-fiction writer. But then I realized that I would rather invent the science than do the years of drudgery and research. Of course, inventing the science immediately meant that I’m making genre movies. I saw that you recently made a zombie movie.

JARMUSCH: It doesn’t quite suit the expectation of the genre. It’s a comedy. I also made a vampire movie that wasn’t really a vampire movie—it’s a love story. But I’m glad you chose your own approach to science. How do you feel about the denial of science today?

CRONENBERG: It’s shocking and bizarre. Can we blame the internet? Science has always been politicized in one way or another, because if you’re building the atomic bomb you can do that.

JARMUSCH: It’s not new.

CRONENBERG: It’s always about politics, but we thought that since the Enlightenment, we’d come away from that. But it’s getting to be the Middle Ages out there in terms of people’s understanding of science. All because somebody changed their mind about a particular Covid vaccine. But it’s an innate part of science that you try stuff. Sometimes it works and sometimes it doesn’t. It’s not a conspiracy.

JARMUSCH: I’m just shocked that knowledge and enlightenment is now projected politically as being a negative thing.

CRONENBERG: Intellect in general is being completely disparaged, and it allows all kinds of strange philosophers to emerge in the meadow of life. A lot of them are religious or pseudo-spiritual as a kind of replacement for science. But there’s so much technology that the survival of the planet depends on right now. Spiritualism by itself is not going to help.

JARMUSCH: I’m with you. I think we’re both atheists on that level. I know you’ve said that social media is horrifying, horrible, and also helpful and positive. It’s very contradictory.

CRONENBERG: That makes it very human. That’s always been my understanding of technology: It’s not a thing from outer space, it’s a projection of us. It can be hideously awful, murderous, and deadly, and it can also be fantastic and brilliant and life-affirming.

JARMUSCH: Do you feel that way about A.I.? I mean, it’s incredibly helpful but also incredibly dangerous. It’s how the tools are deployed. They’re not innately positive or negative.

CRONENBERG: That’s absolutely true. If you put A.I. in charge of your nuclear stockpile, then you’re going to have some problems. [Laughs] But if you ask it to write a précis of a novel that you’re interested in, it can be quite nice.

Tuxedo, Shirt, and Bowtie Saint Laurent by Anthony Vaccarello.

JARMUSCH: I’m not so sure A.I. wouldn’t make a more rational decision about nuclear deployment than some of the people currently in charge. [Laughs] I was thinking recently about how teenagers are glued to their phones. Their phones are an extension of their beings. And I was reading about how bees can communicate over long distances. I started to wonder, maybe this technology is an adaptation. If you take the phones away from teenagers, they don’t know where they are anymore. [Laughs] Is there a Darwinian aspect where it’s helpful in that way?

CRONENBERG: I think the phone has really altered the nervous systems of human beings. I often say to people, “Wait a second, I’m going to look this up,” because I’ve out- sourced a lot of my memory to my phone. I just read a really interesting article talking about why losing a memory is actually an evolutionarily positive thing. You have to be able to forget for your mind to function. So having a phone that you can outsource some important memories to is not bad, but it has to have a balance with life in the real world. You have to eat real food; you have to make love to real people.

JARMUSCH: Well, that’s changing too, I guess. [Laughs]

CRONENBERG: The specifics of it will change. But they don’t necessarily have to change for the worse.

JARMUSCH: I don’t know. I get so depressed by these humans.

CRONENBERG: Humans can be very depressing, yeah. That’s why I really love babies, because they haven’t learned how to be destructive yet. [Laughs]

JARMUSCH: Now we’re getting a little negative. But when I get depressed by the state of the world, I try to appreciate the very strange phenomenon of having a consciousness. I think, “Life on earth is such a fragile, brief thing.” The fact that we’re even here talking to each other is remarkable, and therefore something to celebrate. My friend Joe Strummer from the Clash always used to say to people, “When you get really low, you only have to remember one thing: You’re alive!” So I try to hold that close. But lately, I don’t know.

CRONENBERG: You might be able to find some people who walk around thinking they’re dead. That’s the problem.

JARMUSCH: Right. Your films have tenderness and warmth in them in places, even though critics don’t always project those qualities onto you. The end of Crimes of the Future is tender, warm, and moving to me.

CRONENBERG: Our relationship with the critics, of course, is kind of contentious.

JARMUSCH: I like that quote—I think it’s Godard—it goes, “Critics are soldiers too, but they’re firing on their own troops.”

CRONENBERG: The idea that my filmmaking has always been cold was the critique of The Shrouds. I never felt that I was making cold films. I always wanted to avoid sentimentality and cliched emotional hooks, but cold? There are one or two critics who’ve jumped on that. And I ignore them, of course.

JARMUSCH: They like to find these catchphrases to plaster on you. It makes it easier for them. “Well, the state of the industry’s getting complicated, and now the cinema is dying.” Years ago, before we had streaming services, if we wanted to see a film by, say, Jean Eustache, we’d say, “Oh, it’s going to play at the Bleecker Street Cinema two months from now.” It was an event. Now, my drug of choice is the Criterion Channel. I can see these things whenever I want and that’s great. But there’s something also missing that we can’t put back again.

CRONENBERG: I stopped going to the cinema many years ago. Part of it is my hearing. I watch everything with subtitles, including movies in English. Also the parking is not so great in Toronto.

JARMUSCH: [Laughs]

CRONENBERG: So, I only see movies in real theaters every once in a while, mostly at film festivals, and I’ve found that the projection isn’t always so great. I remember being in Venice onstage with Spike Lee and some others. He was talking about the Cathedral of Cinema, the whole religious aspect of it. And I said, “Spike, I’m watching Lawrence of Arabia on my watch, and there are a thousand camels there. I can see every one of them.” I was joking, but what I meant was, I don’t find the cinema experience all that great. Maybe it’s because I’m older. I don’t feel that communal thing.

JARMUSCH: Right.

CRONENBERG: I do find that people talking about streaming can be very passionate in the way that we were passionate in the movie theater after we saw a film. So it’s different, but I don’t think it’s worse. I also don’t miss working with film. The cutting and editing was a nightmare for me. It was very restrictive. You have so much more control now. And of course, we are control freaks to a certain extent, if you’re making a film.

JARMUSCH: Yes!

CRONENBERG: I have nostalgia for the old films, but I don’t have that Spielberg-esque need to actually shoot on film.

JARMUSCH: I feel the same. And I know David Lynch was very vocal about this, too. The magic of film and the light passing through, that’s all very beautiful, and we appreciate it, but I would never shoot on film again. I don’t have the budget. Quentin Tarantino is lucky to get the money to do that. I can’t. I don’t see the point.

CRONENBERG: Normally I just do one or two takes. In the old days, we would say, “Okay, let’s do one for the lab,” because the lab would always destroy one take in the chemical bath or the sprockets in the machine would tear.

JARMUSCH: Yeah. Well, I don’t know anything else to talk about besides the horror of trying to raise money for our work. [Laughs]

CRONENBERG: That’s the real horror film, to follow some poor filmmaker trying to get the money together.

JARMUSCH: I will say, I’ve had my same American crew for a long time, but it’s very, very difficult with the union here. They almost crushed me, so now my next films will all be shot in France. I’m trying to get a French passport, in fact. Shooting here is prohibitive. It’s stressful, it’s traumatizing.

CRONENBERG: Well, France might end up being the last bastion, having such a diamond-hard cinema history. Different from anywhere else in the world, really.

JARMUSCH: In America, I’m an indie filmmaker, and I’m happy to be that. But in France, I’m an actual film director.

CRONENBERG: And a Saint Laurent model.

JARMUSCH: Along with David Cronenberg. [Laughs] I’ll see you in Paris next week.

CRONENBERG: This was a lot of fun. Thank you.

JARMUSCH: And let’s say hats off to David Lynch, too.

CRONENBERG: For sure.

———

Grooming: Alanna Chelmick using MAC Cosmetics.

Photography Assistant: Jasmine Wi-Afedzi.