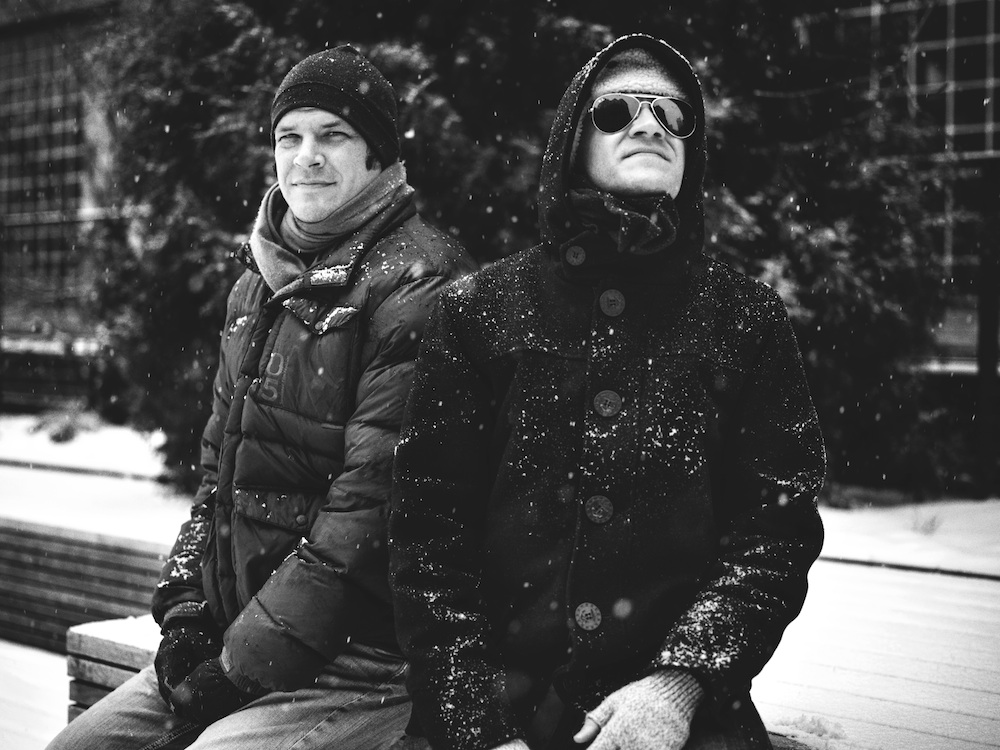

Nathan and David Zellner’s Urban Legend

ABOVE: NATHAN AND DAVID ZELLNER IN NEW YORK, DECEMBER 2013. PHOTO BY CHRISTOPHER GABELLO.

A short history lesson on Nathan and David Zellner’s new feature, Kumiko, The Treasure Hunter: In 1996, the Coen brothers’ film Fargo pictured a briefcase full of money buried somewhere underneath a fencepost on a snowy, nondescript North Dakota plain. In late 2001, a Japanese woman named Takako Konishi left Tokyo for the American Midwest to try to uncover it and died searching in the middle of a Minnesota winter. In 2002, almost as soon as they’d heard the bizarrely poetic news item, the Zellners started expanding it to a screenplay. The project, however, didn’t come together for another 10 years. In that time, the brothers finished two other feature-length films, Goliath (2008) and Kid-Thing (2012), both of which follow lonely, largely silent leads as they search for their respective objects of desire.

Kumiko, which premiered as a contender in the U.S. dramatic competition at Sundance this week, more or less confirms that loneliness is the Zellners’ favorite subject, and their most expert. Rinko Kikuchi plays the film’s titular character, a desolately antisocial office girl who becomes obsessed with the image of that aforementioned black briefcase. As she pores over a staticky, old VHS, she determines to go find it. Her condition is totally tragicomic: The well-intentioned awkwardness with which she navigates the world is almost as entertaining and endearing as her delusion and her freezing death are depressing. Kikuchi’s performance, backed by the the Zellners’ swelling, cerebral sound design, is empathetic in spite of—or, more likely, thanks to—Kumiko’s personal folly and her absurd, often inward-facing emotion.

We met up with the Nathan and David, who wrote, directed, and produced the film, in a hotel lobby in Chelsea a few days after they’d made their final cut, and over a decade after they’d first started work on the project. They were loath to intellectualize Kumiko’s story and much more interested in discussing their efforts to humanize it.

ZACK ETHEART: Takako Konishi’s story is strange and fascinating for so many reasons. What about it made for a compelling screenplay?

DAVID ZELLNER: The first thing that was really fascinating was this antiquated notion of the treasure hunt, which ended with the age of exploration, basically—the idea of traveling to new lands and specifically to the New World in search of this mythical fortune. We liked the idea of applying that to this modern-day setting, because it’s a similar thing. It’s someone traveling from another part of the world to America, but it’s not this mythical fortune passed on by the indigenous people or from some sort of folklore. It’s from a modern-day version of storytelling, which is film, that she gets this information from. We were just interested in that because nothing is mysterious anymore. The world is mapped out and there’s nothing unknown. I liked that idea, taking this sense of mystery and applying it to a setting like North Dakota. And then as more information came out about it, some of it conflicting, we liked the way that the story kind of took on a life of its own as an urban legend. Urban legends are just modern folktales, so we liked taking that fable-like quality and applying it to something in the present.

ZACK ETHEART: Did you feel any obligation to the represent the details of this woman’s life accurately?

DAVID ZELLNER: There’s no way you could get it exactly, so what we wanted to do was to have it connect on a universal, more human level around these themes of loneliness and isolation and personal fulfillment. We wanted to create a fully fleshed out character that people could relate to in that way. With this particular character, all those things are very amped up, but we just tried to suggest the very human things led her to where she ends up.

NATHAN ZELLNER: Kumiko’s obsession is maybe one that is a little hard for people to identify with—everybody knows that certain things are real and other things are imaginary. So we wanted to take a very naturalistic approach to the film, because we thought the more we humanized her as a character, the more you would be accepting her feelings and her decisions.

ZACK ETHEART: Her character is so singular—her interior life is almost the entire substance of the film. How did you decide to cast Rinko in that role?

DAVID ZELLNER: We met her several years ago. There were several different times when the film almost happened, and she was always interested and was just the perfect person for the film. She connected with the material and our aesthetic and our style of filmmaking, so we just knew she was the perfect fit right away.

ZACK ETHEART: How do you go about the work of building a character when she interacts so little with others?

DAVID ZELLNER: We like the idea of how they interact with whatever they’re exposed to in their environment.

NATHAN ZELLNER: The setting where the character is living and how she interacts with that setting—that can all say a lot about who she is without her having to spell it out to another character on screen, which we tend to avoid. We like it to be a bit more natural. Nobody really walks around the world proclaiming who they are. [laughs]

DAVID ZELLNER: If they even know who they are.

ZACK ETHEART: The sound design and the score in Kumiko feel really important in the absence of dialogue.

DAVID ZELLNER: Yeah, a lot of times we’ve done films where we’ve said, “Let’s see if we can do this without music.” But then we love music so much and love what you can accomplish with it. That said, we don’t like doing wall-to-wall score, which I think is a trend that’s a little tiresome because you never get a breath from it. It starts to resonate less and lose its impact.

ETHEART: Where does your interest in isolation come from?

DAVID ZELLNER: [laughs] It’s nothing personal. I think it’s because it’s a very human thing that affects everyone. It’s a part of the human condition and I feel like there’s something very interesting about it because of that. But we haven’t intellectualized it beyond that.

NATHAN ZELLNER: It seems like everyone deals with loneliness. Like David said, it’s universal. It’s interesting how people negotiate the idea of being an individual with the idea of being alone. They can become aggressive, they can become absurd, they can shut down, they can open up.

DAVID ZELLNER: We like to try to ride that line between humor and pathos.

NATHAN ZELLNER: Maybe that’s why the story was so interesting when we first heard about it. It had a little bit of everything—a little bit of sadness to it, a little bit of weirdness, and a little bit of humor.

ZACK ETHEART: How exactly do you write and work together? What does your collaboration look like?

DAVID ZELLNER: I think growing up as brothers definitely lends itself to that kind of workflow. When we were little and making home movies, we didn’t know what writers or directors or producers were; we didn’t know what any of those titles were. We were just making movies. There are no boundaries. It was nice: We could just explore different roles in making these things without being bound to specific titles and could see what our strengths were. Things are more regimented now, obviously, but in terms of the way the two of us work together, there’s still no hard and fast delineation. We don’t think it’s necessary.

For more from Sundance 2014, click here.