David Harbour Builds a House

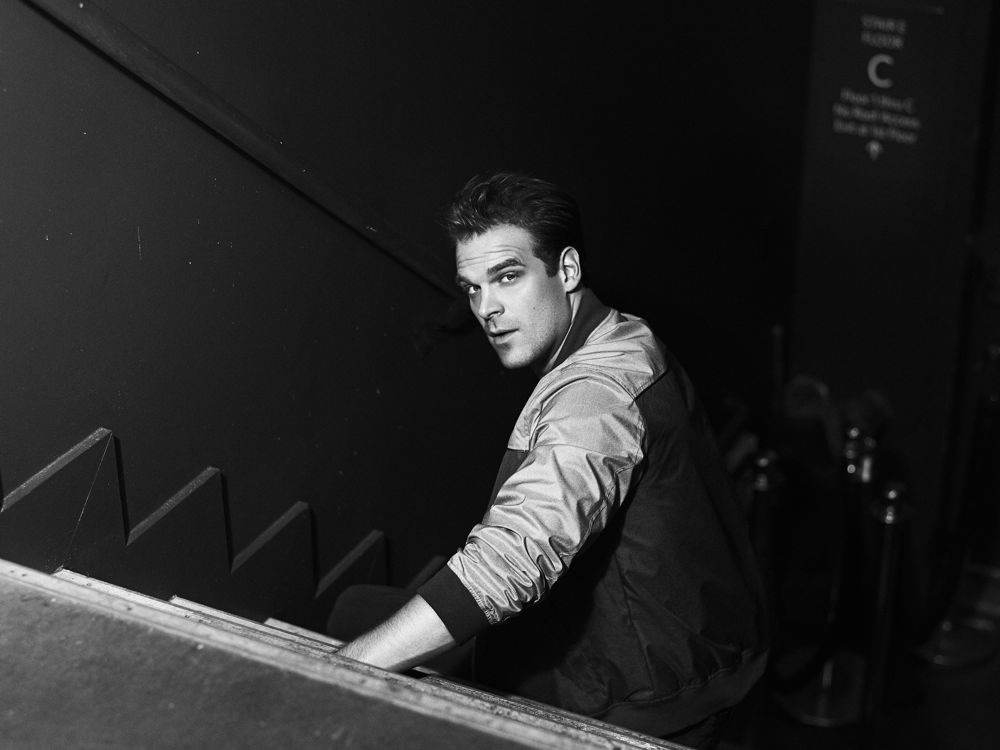

ABOVE: DAVID HARBOUR AT THE JAMES HOTEL IN NEW YORK, JULY 2014. PHOTOS: WENJUN LIANG. STYLING: SAVANNAH WHITE. GROOMING: LAURA DE LEON FOR JOE MANAGEMENT USING CHANEL. SPECIAL THANKS: DAVID BURKE KITCHEN AT THE JAMES HOTEL.

Ask actors David Harbour and Billy Crudup how they met, and they’ll launch into a string of jokes: “OKCupid!” “Tinder!” In reality, the New York-based theater veterans first crossed paths at the opening of Tom Stoppard’s play The Invention of Love on Broadway, or “something like that.” They became friends several years later while working on another Stoppard play, The Coast of Utopia, at Lincoln Center and have since acted together in the film Thin Ice. “My experience of you was just jealous, envious rage that you were so good at that play, and so much better than me,” jokes Harbour. “I remember trying to undermine you at every turn. Trying to kill laughs with coughs! It didn’t work…”

September is a busy month for the 40-year-old Harbour: On Sunday, his television series Manhattan will conclude its first season on on WGN. Last week, his film A Walk Among the Tombstones came out in cinemas. This Friday, he’ll release Equalizer, another thriller in which he co-stars with Denzel Washington and Chloë Grace Moretz. In both Tombstones and Equalizer, Harbour plays the villain—a role at which the Dartmouth grad is particularly skilled.

Here, Harbour discusses his upcoming projects with his good friend Crudup.

BILLY CRUDUP: I’ve got a number of questions.

DAVID HARBOUR: You have questions? No you don’t.

CRUDUP: I only have about 30 seconds of questions. And that does not leave room for answers. [laughs] Oh boy.

HARBOUR: I knew it was a good idea to get you to do this.

CRUDUP: First question!

HARBOUR: Lay it on me. I can’t wait.

CRUDUP: This is for the film Walk Among the Tombstones, right?

HARBOUR: [laughs] Yeah, it’s also for Equalizer, but basically.

CRUDUP: Okay, first question.

HARBOUR: Let me give you a little backstory on me before you interview me. I’m doing this movie Walk Among the Tombstones and then next week this movie Equalizer, with Denzel Washington. Two action movies; one is more crime-thriller-y New York-y and the other is more blockbuster-y. The Denzel one is more blockbuster.

CRUDUP: Gotcha.

HARBOUR: Sorry I interrupted.

CRUDUP: I lost my train of thought there for a second. I have it right here. Okay, first question. I saw the poster for Walk Among the Tombstones. You look different. The question is did you put on height for the role?

HARBOUR: I had plastic surgery where they crack your shins and they extend the bone.

CRUDUP: Is there anything you won’t do to transform for a part?

HARBOUR: Yeah, I won’t get in shape for a part. I refuse. I’ll only get fatter and fatter as my career progresses.

CRUDUP: Mike Carlsen saw the movie the other night and said you were out-fucking-standing.

HARBOUR: Thank you Mike Carlsen.

CRUDUP: That’s not a question, just a compliment. You and I have worked together both on stage and in film, so I’m familiar with your process from the perspective of a colleague, somebody who works with you, watches the way you go about your work and then ultimately have to act with you. I experience you as a very intelligent, clearly focused, dedicated actor who’s also really available in the moment. But my question for you is, how do you experience yourself as an actor in those two different mediums?

HARBOUR: That’s a good question!

CRUDUP: Thanks. Then I’m going to end it right there.

HARBOUR: I think I’m very hard on myself, I think I’ve always been very hard on myself since I was a kid. I heard Ellen Burstyn say something about this divine dissatisfaction of the artist years ago when I was growing up; I think it was an interview for Inside the Actors Studio. She talked about how you get to a certain point but you can build a box, you say, “Ooh, I built a box.” But then your first thought is what would it be like to build a house? And you constantly putting extra pressure on yourself and thinking, “I can do that better, I can do that better.” I’m constantly very hard on myself about stuff like that. But I’ve sort of come to, over the years, accept my process. I was very resistant to my intellectualism for a while. I do start with an intellectual idea for a character. A lot of the times it’ll be the opposite of what I feel like is on the page, or it’ll be just an idea that I read in a psychology textbook or in a philosophy book. I’ll apply something to it that I can start to tinker with. For a while in my life I’ve been very derogatory, saying, “I want to be more visceral, I want things to come from my body, more organically.” Over the years, I’ve [realized] this is a good place to start. You can start anywhere, I think, in a character. You can start intellectually, you can start from the body and hopefully arrive at the same place, which is a well-rounded performance.

CRUDUP: I think that’s an excellent point that you make. For the creative process, ultimately what makes the currency that each of us have is—hopefully in addition to some craft—is our individuality. And if you don’t begin to apply that in some way, whether it’s the choices you make moment to moment or the choices you make in your process, then you’re not going to be reaching the full potential of what you really have to offer. For you, you could start a character from an intellectual place based on something you’ve read recently or it doesn’t matter; what you’re doing is you’re applying your own individual creative take, which ultimately from the moment you’re involved makes that character yours. I’ve definitely experienced your ability to internalize a novel voice, something that really only you could do. You said this dissatisfaction that you have, is there a correlation, for you, between that and feeling, “Listen I’ve been successful in my career, so how can I stop this process of beating myself up?”

HARBOUR: That’s a personal journey that I’ve been on for a long time. I think it reflects the choice of being an actor from a very young age. There’s something deep inside of me—this is very grandiose and philosophical—but that struggles with the idea of being human in some sense. Part of it is the struggle of when you’re starting out and auditioning and being rejected a lot—there’s a constant rejection that you incorporate into yourself. It’s like a moth to a flame. I think my fundamental neuroses and this profession causes me to constantly seek what is inside of myself—constantly self-reflecting and self-evaluating.

CRUDUP: Do you see a point where you get past the breakers? You’re going out of the inlet, you get past the breakers and then there’s some calm ocean out there? Or is this part of what’s going to be a lifelong process that you have to deal with? I do see actors sometimes who are seemingly pretty satisfied with the way things are going and that’s an unfamiliar feeling to me as well. I’m interested in what you imagine could be the point at which there’s some smooth sailing for David Harbour. Oh Harbour! Hey, look at that!

HARBOUR: [laughs] You brought it around.

CRUDUP: [laughs] I should have started with that. Dammit. So give it me, what’s smooth sailing for David Harbour?

HARBOUR: What happens is that opposed to looking for calm water—how about this for a metaphor—you get better at swimming. You’ve got to get stronger, being able to swim in the breaks. Because naturally, I’m drawn to some form of struggle and some form of experiencing life in a deep way. I do, of course, like to relax and chill out, but I don’t necessarily know if that’s my natural state. My natural state is a state of an explorer—a performer, but someone who wants to explore their experience and reflect on their experience more than just lie on the beach. Even when I go on vacations, I get stressed out if I’m at the beach for like two days. I’m like “Can’t we do something? I can’t just sit there.”

CRUDUP: [laughs] That’s horrifying. We need to get you to a spa.

HARBOUR: Yeah, me and you in a spa would be horrible. We’d both be freaking out, peeling the facials off. I think most of it is about self-acceptance. You start to realize that there’s actually no escaping yourself—that boy that I was when I was young, there’s definitely a large percentage of him in the man I am today. At that point, you start to say, how am I going to swim in this particular batch of ocean that I’ve chosen to be in?

CRUDUP: As actors, we are in a unique position to observe ourselves because we spend too much time trying to understand other people. We have to use our body, we have to use our mind, we have to use our character, so you want to know the instrument that you’re using as well as you can. It can also can get you stuck. People can become self-obsessed. And it’s obviously not hard to do that at all, but you pointed to one of the things that I think creates a lot of tension for actors and that’s this idea of rejection. I was trying to explain to somebody the other day who doesn’t quite understand what actors do, what the experience of going about trying to get a part is, and hoping that you do your best and maybe not being in an environment that helps you be your best and then the movie comes out, or maybe it doesn’t come out. Or it comes out and it sucks. Or it comes out and the critics hate it or the box office does really terrible. There are so many different stages of rejection. Is there something in film that you’ve experienced as a particular kind of heartbreak? Perhaps you had given a performance that you thought was successful in one way and when you saw it, it wasn’t?

HARBOUR: [laughs], I was just talking to someone about this yesterday. What I have in this movie [A Walk Among the Tombstones] is the opposite for that experience. I’ve had so many of those experiences that you’re talking about, [but] Tombstones was the opposite of that. To see if Liam [Neeson] was going to decide to do the movie, we all got together in a hotel room. I don’t know if you’ve done these before, but I’m sure you have.

CRUDUP: I’ve been to a hotel.

HARBOUR: [laughs] The stars decide whether they want to do it or not and they have five actors come and read all the parts with the star. The casting director is there, the producers are there, and the director is there. The director was Scott Frank, and I’d never met him before, but we went to this hotel room and I had like eight parts that I was reading, one of which was like “Deli Owner Number Three.” And one of the parts was this character Ray that I play and who’s the killer. And Ray, as described in the script, is very, very different from me. He was supposed to be short and rotund and his partner was supposed to be tall and Frankenstein-ish. We sat down and did this read-through and I connected with a part really quickly and I felt really great about what I did. But I’ve had so many of those experiences where I will do this in a hotel room or at a reading or something, you feel like you did a really great job, you shake hands with the director and then they tell you that they’re not even going to see you for the part—”We’ve already cast Chris Pine or Billy Crudup and we’re not even going to let you read.”

CRUDUP: Wait, I got a part?

HARBOUR: [laughs] When they decided to make this film, Scott came to me and was so embracing of what I did at that read-through, and just let me take the character and didn’t even want to give me notes—just wanted me to run with it. It was such a different experience than what I’ve had when I’ve tried to audition for other villains in the past and I’ve gotten a lot of notes saying, “Can you be more evil? Can you relish it more?” All of these notes that to me feel not very on-the-nose, not what I want to do. When I play a villain I generally tend to play the opposite, I try to make a caring individual or a questionable character, something that’s not evil. I’ve gone to so many auditions where they’ve said, “He’s just not evil enough.” And I expected to walk out that room and never hear from these guys again and then have it offered out to a star. And this guy really took a shot. Scott Frank really took a stand for me and it was so, so gratifying.

CRUDUP: And that experience persisted through the making of it and you felt like there was evidence of that when you saw the movie?

HARBOUR: Yeah, it was this great collaboration. He’s someone who gets me and gets my process, and you come across those people once in a while in your career. Anytime there’d be an argument—and all of the departments were terrific, but I had specific things that I wanted, like I wanted him to be in sneakers, and the specifics behind that were just that he might have to run, he might have to like take off. He has to be prepared.

CRUDUP: I love little situations like that.

HARBOUR: It’s little turns like that, that are never explained and that are never part of the movie, but, when I walk around the set, I know that this is going on. Scott was always so gracious to me. He’d be like, “I defer to David. He knows this character better than any of us.” That’s so rare of a thing. The whole making of that movie was just really really fun because of that.

CRUDUP: That’s killer. And what about the Equalizer? Tell me about that experience?

HARBOUR: It was cool. I like those guys a lot. Antoine Fuqua, have you ever worked with that guy?

CRUDUP: I have not, no.

HARBOUR: He’s really, really smart. He’s like the boxer; he’s big and jacked and scary and has a boxing thing outside of his trailer so he beats the shit out of it at lunch. It’s really intense. And then he goes on set and he’s a sweet dude; he has such a big heart. He’s such a complex guy. Like the Equalizer, it’s a big blockbuster action movie, but I cried. There’s this relationship between Chloë Grace Moretz and Washington where they just have this fatherly relationship and he does the action stuff so well, but he also has the heart to let scenes play in a really rich beautiful way. It was fun because we got to do a lot of improv on it too, which I don’t find that I get to do a lot of in movies.

CRUDUP: Is that something that interests you?

HARBOUR: I love it, man. Do you like it?

CRUDUP: I like it at the times that I don’t suck at it. And then I don’t like it when I suck. [laughs] I get so uncomfortable.

HARBOUR: [laughs] You get so uncomfortable just talking about it?

CRUDUP: Well look at what you’re saying about it. Sometimes you have an innate connection to a character that you probably can’t even explain. Some characters, I’m sure I can improvise easily in any context and other characters, not a freaking clue.

HARBOUR: Yeah, it’s true. Usually it depends on whether or not I’ve read the whole script.

CRUDUP: [laughs] Sometimes they’re so long.

HARBOUR: 120 pages, are you kidding me? I feel you. When it’s bad it’s bad. I like it because it’s scary. Like you fuck up and you do a really bad take. Not like a kinda bad take where everyone goes, “Okay, we’re just going to move on.” A take where it’s completely unusable. Oh, you’re just awful.

CRUDUP: Check the camera, you might have broken it.

HARBOUR: Exactly! It’s nice to feel like you’re really on the high wire that way and you can really fall. Denzel and I had this big scene at the end of my arc in the movie where we improv like a three-page scene. We started out and I didn’t know what the hell I was doing, but slowly it grew and Antoine had the courage and the clout to take the time for that type of work. It’s my favorite part of the movie.

CRUDUP: I know we talked when we were working in Minnesota [on Thin Ice] about things we are interested in doing. What are the things that you are interested in pursuing? Do you have any roles that you’re chomping at the bit for?

HARBOUR: Yeah. I have one that I’m dying to do, which I want to talk to some people this summer about. I don’t know if I should tell you about it. [laughs]

CRUDUP: Yeah, don’t tell me exactly because then I’ll try to steal it.

HARBOUR: [laughs] There’s a very small supporting role for you in it though, that I like.

CRUDUP: I’m not available.

HARBOUR: It’s got a really sweet couple’s scene…

CRUDUP: Not available.

HARBOUR: But I really want to do a play again. If I can sit down and finally finish these couple things that I’m working on writing, I’d really like to start make some of my own small movies. The more I work in the film business the more I see that those guys, the directors, have the most fun on set.

CRUDUP: Can you explain to people, because I have been unsuccessful in trying to explain to people that when I say, “I want to do a play,” I’m not just kidding around—”This might be fun.” Or “I need a break from the Hollywood scene.” I’m actually interested in the craft of theater. It’s not a novelty.

HARBOUR: I’ve had a different experience than you though, because you were, in my mind, a big movie star coming out of the gates. You had a very successful film career. And I’ve existed in this place where I’ve had to do theater to pay the bills for a long time and I haven’t had the opportunity in film that you have. But two years ago when more films started happening for me, more television started happening for me, I hit this place where I had that moment: “I really like to do plays.” And making movies is hard work and not that fun to be honest. But the finished product is exciting as hell. When you go and see it all cut together and you sit in the theater with you popcorn and your Coke. That is exciting as hell for me, but that, in my mind, is the best part of the process. Whereas theater, people think that the best part of the process is the applause in the end, [but] it’s almost like a football team—we get to go play football. People go, “Don’t you like it when people cheer in the stands?” Yeah, but what I really like is watching a great play. Like when I throw a ball to that dude and he caught it and slammed it down on the ground and scored a touchdown, that feeling, the rush that you get. I never really get that in movies; I only get that feeling when I’m on stage in front of a live audience doing a great play with people that I love.

CRUDUP: Two things: A, I think you said it very well. And B, I can’t think of anything that people would like to read more than two actors talk about sports.

HARBOUR: [laughs] What’s football? Is that the one with the stick where they hit the ball?

CRUDUP: [laughs] It’s the one with the hard feelings and the yelling.

THE FINAL EPISODE OF MANHATTAN AIRS THIS SUNDAY ON WGN. WALK AMONG THE TOMBSTONES IS CURRENTLY IN THEATERS. EQUALIZER COMES OUT THIS FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 26.