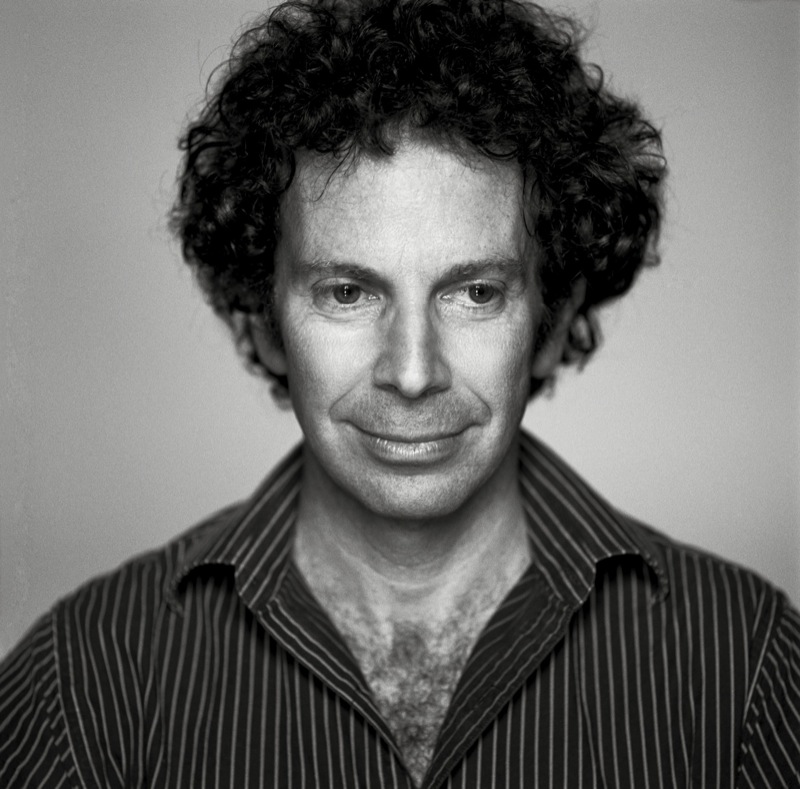

Charlie Kaufman

Some people just don’t fit the formula. But then the formula seems somewhat antithetical to what Charlie Kaufman does. As a screenwriter, he is best known for his two mind-bending collaborations with director Spike Jonze, Being John Malkovich (1999) and Adaptation (2002), and another pair of colorfully inventive films with director Michel Gondry, Human Nature (2001) and Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (2004). But the 50-year-old Kaufman seems to have saved his trippiest project for himself: His directorial debut, the recently released Synecdoche, New York, stars Philip Seymour Hoffman as a theater director whose autonomic functions are, one by one, beginning to shut down as he contends with both his cast and the women in his life, and as he struggles to build a life-size replica of Manhattan as part of his new play. Synecdoche marks a distinctive first film for a scribe turned auteur whose predilections for turning the age-old conventions of plot and character inside out (and upside down) are matched only by his ability to do it all with surprising heart and soul. David Cronenberg recently spoke with the notoriously reclusive Kaufman about the road to Synecdoche, New York.

DAVID CRONENBERG: It’s kind of a classic thing: You’re a writer—frustrated at times with how some of your screenplays have been handled by directors—and now you finally get to direct your own movie. How was that experience for you?

CHARLIE KAUFMAN: I think I’ve had pretty good experiences for the most part with the people who have directed my screenplays. It’s more that I wanted to see what it would be like if I didn’t have to collaborate with anybody—you know, to have a sense of purity of the thing from beginning to end. I liked doing it. It’s really different from writing. Directing is a more pragmatic experience, where you have to deal with the restrictions of time and money that force you to make certain decisions you don’t have to make when you’re writing.

[Directing] was a big learning experience for me because I had to deal with every aspect of everything-all this constant decision-making, with people asking you questions at every moment, and you have to have answers for them all. And, you know, the hours are not great.Charlie Kaufman

DC: Did you find it shockingly different from what you imagined?

CK: I think it was fairly close to what I had imagined. I have a background in theater, so I have experience with actors. I like actors—I used to be one. There weren’t any enormous surprises. But it was a big learning experience for me because I had to deal with every aspect of everything—all this constant decision-making, with people asking you questions at what seems like every moment, and you have to have answers for them all, and that kind of thing. And, you know, the hours are not great.

DC: Was this script ever a project for somebody else to direct, or were you always thinking that you would not let it go?

CK: In fact, it was somebody else’s first. What happened was that Spike Jonze and I had been approached by Amy Pascal at Sony [Pictures] to do a horror movie. We worked with her on Adaptation, and she really wanted to work with us again. So Spike and I talked about ideas and about what was scary. It was important that it be something really scary and not like a typical horror-movie thing. We had a vague idea and direction, and we went in and pitched it, and I guess she was so interested in us as a team that she said, “I don’t care what it is. Whatever you want to do.” So I went off to write a script. It usually takes me a while to write scripts, and this one was no exception. A couple of years into it, Spike started working on this movie, Where the Wild Things Are, and he was setting that up as I was turning in my draft. He still wanted to direct the movie, but he wanted to do Where the Wild Things Are first, and I didn’t want to wait. I thought, This is going to be five years that I’m going to be without a movie, at least. And the script ended up being something very personal and idiosyncratic. So I asked Spike if he would step down as director, and he agreed. And that’s what happened.

DC: Are you working on any screenplays now that are committed to other directors?

CK: No, I’m not. I’m not working on anything. I was trying to write something new . . . I guess the goal for me now, at least at this point, is to try to direct again. So I guess the thing I’m thinking about, which I haven’t even proposed to anybody, is to be able to direct my own scripts. I think now that I’ve tried directing, I’m not interested in doing adaptations anymore. I could do an adaptation of someone else’s work that I would write, but the idea of taking someone else’s material entirely doesn’t interest me. One of the things that I found really helpful, at least in my mind—and I’ve never discussed this with the actors or with the people I work with—is that being a neophyte in directing, I feel like I have a kind of authority simply because I’m the writer as well. If I were doing somebody else’s script or I adapted a book by Philip Roth, on set there could be a million different interpretations of the material and people could argue with me. Certainly on Synecdoche, New York we had discussions and arguments, but I felt like I had authority.

DC: Which was undoubtedly an illusion. [laughs] But it’s true that the dynamics of the cast and crew are pretty interesting, aren’t they? It does feel like a military operation at times.

CK: There is a lot of management going on. Maybe that was the biggest surprise-just the amount of tending that I had to do. The different personalities . . . It’s not my way, and it’s never been my function before as a writer. I tend to be a moody and somewhat withdrawn person, and I felt very clearly that I had to throw that away because that wasn’t allowed here—there were other people who were going to be filling that role. Sometimes it became exhausting, especially around the eleventh hour of the day. So I wasn’t allowed to pout in any way, which is another thing I like to do.

DC: Because when you’re a director, you can’t be that way. People need to hear from you. They need encouragement and support from you. So you have to somehow find generosity of a particularly weird kind in yourself, don’t you?

CK: I’m the father of . . . Well, she’s 8 now, but parenting is a relatively new experience for me, and I feel like there is that same kind of thing. It’s kind of like, “Okay, this is my job here. I can’t be so insane around this person. She needs me not to be.” That comes across in all sorts of ways, like my trying really hard not to transmit my concern, because I have a lot of anxiety about, you know, medical things for example. I don’t think I’m particularly good at it, but I’d had the practice when I went into shooting Synecdoche. It can be somewhat gratifying, too, because I don’t have that relationship with other adults where I need to comfort them or they come to me for that.

DC: I’ve sometimes said that being a parent is actually good preparation for being a director, but it’s often misunderstood to mean that actors are like children.

CK: No, that isn’t true at all. So when I found myself in that situation, I tried to be successful. And when it worked and I figured out how to communicate that things were good-or at least okay-then I felt pleased.