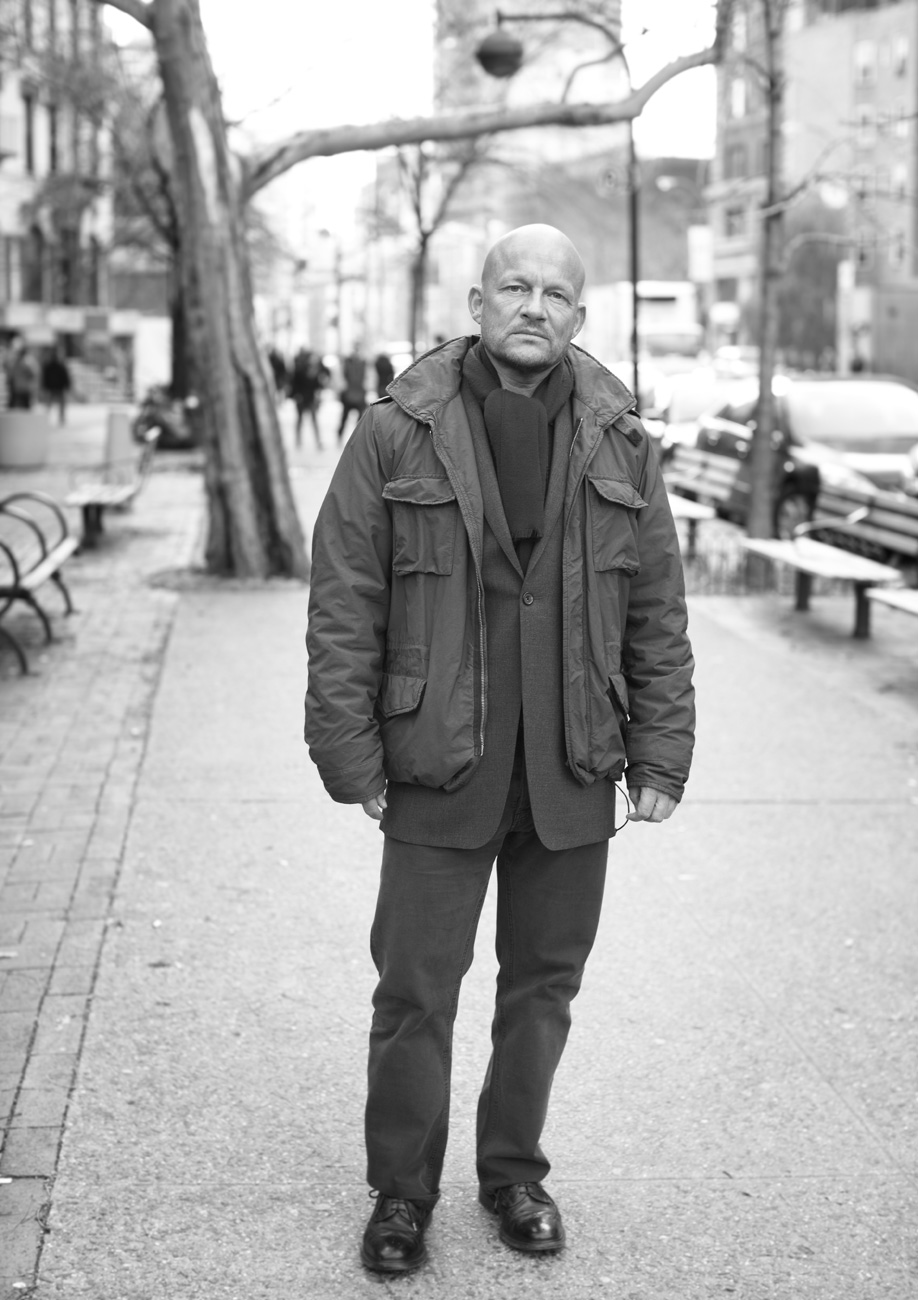

Vincent Van Duysen

The term minimalism has been used so often and so indiscriminately in art, architecture, and fashion to describe a paired-down aesthetic that it has lost most of its currency. Along with words like modernism, pop, or international, minimalism mainly serves as an empty lexical placeholder in a culture that often seems to cling to the style out of fear of more personal expression. -Belgian architect and designer Vincent Van Duysen has been called a minimalist throughout his career, but at the age of 47, he hardly shies away from expressing himself. In fact, his monastic constructions, clean lines, almost sacred geometries, and sensual uses of light, shape, and natural materials make up a decidedly individualistic and emotional body of work.

Van Duysen got his start as an assistant to Aldo Cibic in the legendary Milan studio of Ettore Sottsass. In 1990, he went on to establish his own studio in Antwerp, Belgium. He comes from the long and rarefied line of architects who refuse to concentrate only on the shell and also project a sense of living that is as much inside as outside. Van Duysen calls it the “art of living,” and he’s done much to refine that art in industrial design, having created everything from slender outdoor furniture and earthenware containers to Swarovski crystal chandeliers. His architecture is more purist than minimal, and an exhaustive sweep of it can be seen in a new monograph, Vincent Van Duysen: Complete Works (Thames & Hudson), which is out this May. Also this spring, his studio will show several new product designs at the Milan Furniture Fair, including a cupboard system and bathroom furniture. And in September, the Antwerp youth hostel he designed is set to open. It’s hardly a surprise that Van Duysen is friends with fellow Antwerpian and purist of fashion Raf Simons. The two recently spoke about what minimalism means to them as well as the kinds of houses they really want to call home.

You need to be comfortable in a house the same way you need to be comfortable in a piece of clothing. you and i like the pureness of an object. the architecture of a room can be an object as can a piece of clothing.Vincent Van Duysen

RAF SIMONS: Okay, Vincent. Obviously I know quite a lot about you because we are good friends. But what I really don’t know about is how you grew up. What was your family like?

VINCENT VAN DUYSEN: I grew up in a provincial town between Ghent and Antwerp. I was an only child in a very, very protected environment—and a very conservative one. I studied Latin and Greek in secondary school—not mathematics, as you might think, seeing as how I became an architect designer. But I wasn’t that kind of kid. I was very emotional—and I still am—very sensitive to what was going on around me. I was very observant. And I was also in one way fragile and in another way strong. I was in a protected environment not just with my parents but because I went to boarding school for eight years before I went to art school. My parents wanted me to study law and choose a much more pragmatic profession. I was never supposed to go into art. But I was a sensitive boy. I chose art. I wasn’t even thinking about architecture at this time.

SIMONS: I’m shocked by how much we have in common. I was also an only child. My family was more working-class—my dad was in the army and my mom was a cleaning lady her whole life. I was completely unaware of the possibility of art. I was supposed to be a doctor or a lawyer as well, although my parents said, “We never had the possibility to study, so you do what you want to do.” I became an industrial designer. That’s all I was aware of.

VAN DUYSEN: I was pretty isolated. As a kid, I was friendless, and I never did sports. When I was 11, my family moved from the city of Lokeren [in Belgium] to a house in the country. I loved the farmhouse—the cows and horses and birds. I always wanted to have animals around. I adored animals. My mother hated them because she thought they were dirty, but they were so sweet. They give you all the attention you want, and there is such tenderness in them. That compensated for the harsh environment of the city and school. I was also very passionate about fashion and dancing. I took ballet courses in the city. I was attracted by the more unconventional kids on the street there. I was already an alternative person. I went to youth clubs. I was a kid of the ’80s, really following the music and the clothing from that time. During the week I was being taught in a very strict boarding school, and on the weekend I was blowing open. It was all moving toward art. I didn’t want to study architecture because I have no affinity for the application of math and physics. I was actually supposed to study fashion—which, to me, is art. My parents had friends who were architects, and I came into contact with them. And one sculptor who was giving lectures in architecture told me that architecture would be best for me because I could incorporate my sensitivity and creativity. Actually, that’s what I did. I’m happy that I’m an architect and that I’m also not behaving like this typical architect and that myarchitecture is different from what everyone else is doing. I was even thinking over the weekend that at one point I might want to design a small collection of clothing. When I graduated in ’85, I was still so curious about the world. I wanted to know more about it and about the art of living, which for me was much more linked to real architecture. Design is more a part of living, which was why I moved immediately to Milan.

SIMONS: Were either of the houses that you lived in growing up modern?

VAN DUYSEN: No. They were both classical houses.

SIMONS: I guess I’m trying to figure out where your style came from. I think of your work as very purist, very modest, and very livable—like you take care of the people who have to live and work in these spaces. I’m interested if that is how you define yourself. Because people define the work I do for the Jil Sander brand as being very minimal. But I don’t think it’s very minimal. It’s more purist—and those two things are very different.

VAN DUYSEN: When you think about minimalism, you are typically referring to the American minimalist art scene. And that was a term that was used a lot in architecture. But I think you and I don’t really like to be connected to any movement or form because we are following our hearts and instincts. We’re very intuitive people. And as you said, you are tailoring your work to a certain audience so it can sometimes look conservative because it is about purity and essential forms. You need to be comfortable in a house the same way you need to be comfortable in a piece of clothing. You and I like the pureness of an object. The architecture of a room can be an object as can a piece of clothing.

SIMONS: It’s a very thin line, I think, the difference between purist and minimal—specifically in architecture. And I think you need to place those terms within the context of the world’s time—that moment in history that would be defined as “überminimal.” Take for example the house of Linda Loppa [the former head of the fashion department at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts] in Antwerp, which was like 2,500 square meters of concrete. The living room was 800 square meters and had two chairs, and the bedroom was 400 square meters and had one bed. When I first met Linda, I was 23 and just coming out of school. I was extremely obsessed with that house. For me, it was like the überpurist or the überminimal because I didn’t really split up the definitions yet. But now, after having lived in the houses I’ve lived in and becoming more and more of my own person, I’m not sure I could ever live in a space like that. Then there is your house in Antwerp, which I find purist but I don’t find minimal—because there is nothing that disconnects the person from the environment. It’s not a person versus the space—it’s all one. That’s why I think your work is in contrast to über-überminimalism in contemporary architecture, which I find impressive to look at but not so impressive to have in daily life. Who are your favorite architects in history?

VAN DUYSEN: I love the Romanesque style, especially that of some of the French cloisters because it’s pure contemplative architecture where you can really get to the essence of the space and the solidity of the materials. I love the work of Mies van der Rohe, which really jumps us into modernity. I admire his open-plan vision and use of materials and detailing. I love Luis Barragán and recently visited a couple of his places in Mexico. I’m even more intrigued about him as a person now that I feel a connection to his works. He’s like a really great mentor for me. And there is a Dutch architect who was also a monk, Dom Hans van der Laan, who had his own system of proportions. And then there are many forms of architecture that I love that are tribal, whether they’re in Japan or somewhere in the Atlas Mountains, where people without studying architecture come to realize their own environment within nature and have their own vision about how they should live. That’s a big inspiration for me—human beings all over the world with their own houses.

SIMONS: Is there one particular house where you would say, “It would be a dream for me to live in that house.”

VAN DUYSEN: Well, there is Barragán’s own house in Mexico City. I wouldn’t mind living there. It’s like a sacred, contemplative place with a focus on the beauty of the natural materials.

SIMONS: Could you live in a house that wasn’t designed by you?

VAN DUYSEN: It’s a good question. My first reaction would be to say no. Its very hard to find someone else who is complementary with me. For a house like Barragán’s, which I finally got to visit after seeing it only in books—I had that feeling in his house. If there ever would be the kind of soul mate that he could have been, then I would say that yes it is possible—it may even be a very important moment. But it is weird. A house is something that was already in an architect’s own skin—his own environment, his own aura—and then taking it over and doing things to it and giving it added value, that would not be easy. But I do think it would be interesting.

SIMONS: I usually prefer to not wear my own clothes. But it’s a different relationship. The advantage we have with fashion and people in high fashion is that they wear impossible clothes but those clothes only last for six months. So it’s a little bit easier to live with, I suppose.

VAN DUYSEN: But that’s why I have almost nothing of my own design in my own house either. . . .

SIMONS: What happens if someone comes to you saying they want to work with you? Is there a set structure for every client?

VAN DUYSEN: It’s intuition. It happens at the moment of the first encounter—that initial contact tells me a lot. I have very good intuition about people, and mostly I can sense when people are coming to me just because of my name, not even knowing any of my work. Then I’m literally not interested.

SIMONS: Do you find it annoying or interesting when somebody already knows very much what they want?

VAN DUYSEN: The success of my projects is thanks to the input, the vision, and the personality behind my client. The best work I do is thanks to a very intense interaction and communication between my client and myself. I love it, to build something up with my client, to share ideas, and to come up with a very unique, tailor-made project.

SIMONS: That’s interesting because I think there is a lot of architecture around that seems the very opposite of that—very attached to a style that isn’t collaborative at all. Earlier you said that you don’t behave like a typical architect. How do you behave then?

VAN DUYSEN: First of all, I’m not this pragmatic architect for whom everything is dictated by mathematical rules. I only started doing houses when I was in my mid-30s. Before that, I was much more attracted by interiors—the art of living—about colors, fabrics, materials, and about designing objects that belong inside the houses of people. Because for me, architecture was not this building or this construction, it was much broader and continuous and multidisciplinary. I like how it was decades ago when every single piece that you designed—a carpet, a lamp, a chair—all belonged to this one thing, a house. And that is what makes me different from mainstream architects. I also use technology in a very understated way. I’m much more of a traditionalist; I really like to work with real natural materials. I’m interested in the personality of the person living there. That’s also the reason I never work with interior designers. I really offer the whole package. I need it to be all in one. That’s why I consider my furniture domestic architecture.

SIMONS: It can go very wrong if someone works with an architect, and then they have to choose their own furniture.

VAN DUYSEN: Exactly. It can go wrong very often.

SIMONS: When I was looking for my new house in Antwerp, it took me about a year. I just couldn’t believe what I saw. Often a building was okay, but then the way the kitchen was put in or the furniture inside was all wrong. I’m very attracted to architects who do the whole thing. I have a big attraction to architecture from the ’50s and ’60s, especially that of the American John Lautner because he had a framework. We talked a bit about your furniture, but I wanted to ask you if you like designing pieces for some of the bigger companies. Is it a different process than designing domestic pieces for individual clients?

VAN DUYSEN: It’s a completely new world, and that process is very complementary to where I want to go with my architecture. These companies have a lot of know-how, they have great research and development—especially the Italian ones—and they know about dealing with execution, prototyping with materials, researching of materials, and they are really very helpful. I was attracted to these people because they appreciate the sincerity in my work, the very humble pureness about it. The big challenge is, How do you distill one piece of my furniture and bring it into this massive industrial process? That’s what it’s all about. It’s very challenging to design. I want to realize a piece of furniture that has the same integrity and sensibility that I try to achieve in my architectural work. There is still a lot of potential for it. There is a feeling in this world that everything is about screaming. Design is a screaming world. If you see every year what’s happening on the furniture front and the amount of screaming objects that everyone is showing, it’s hard to find a piece which comes from big industry that still has the integrity of a designer and is a beautiful one-off piece that can blend in to whatever environment it finds itself in and makes the end user happy. That’s what I want to do in my work.

SIMONS: What is your ultimate dream project?

VAN DUYSEN: It could be like a museum. Definitely, a museum. Or a dairy. It could also be a cloister or something related to religion.

SIMONS: Okay, final question. After a busy day of work, when you return home, what is the first thing you always do?

VAN DUYSEN: I have my dog with me. But the first thing I do is open a bottle of red wine and I drink a glass. That’s the first thing I do.

SIMONS: The first thing I do, even before taking my coat off in winter, is I put my fireplace on.

VAN DUYSEN: That’s the next thing I do.

Raf Simons was born in Neerpelt, Belgium, and now is based in Antwerp and Milan. In addition to designing his eponymous fashion line, he serves

as creative director of Jil Sander.