New Again: Gore Vidal

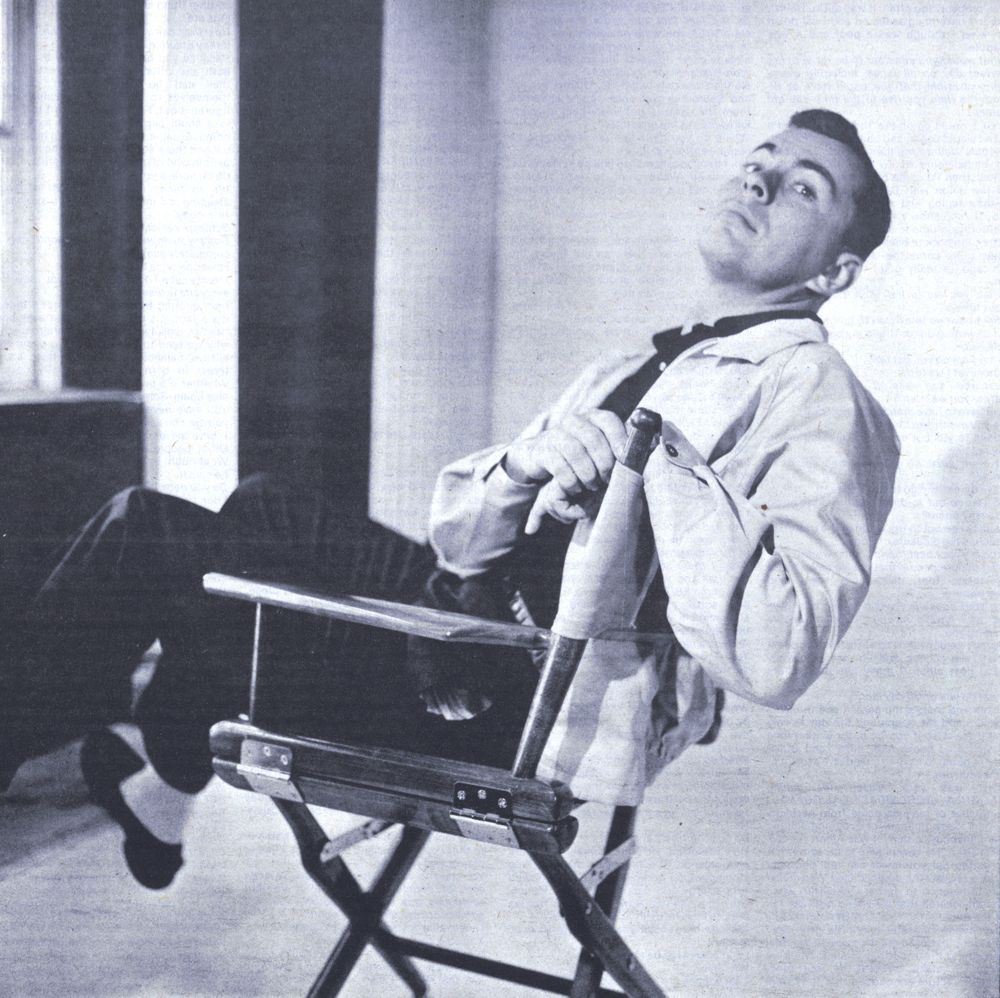

ABOVE: GORE VIDAL IN 1950, PHOTOGRAPHED BY HORST. PHOTO COURTESY OF SONNABEND GALLERY.

UPDATE [August 1, 2012]: Last night, Gore Vidal died in his home at age 86. Our best wishes go out to his friends and family.

On May 1st, the nominees for the 2012 Tony Awards were announced. Among the plays nominated for “Best Revival” is Gore Vidal’s The Best Man, written by the playwright-author-journalist (ahead of the 21st century multi-hyphenate trend) in 1960. When Interview spoke with Vidal in April of 1976, we discussed, among other things, The Best Man and Vidal’s opinion on the theater in general ( it seems he does not, or did not, “much like plays”). Ever outspoken, Vidal also regaled Interview with his opinions of Norman Mailer, Truman Capote, Richard Burton, Elizabeth Taylor, John Simon, the Democrats, and the Republicans (all unfavorable), as well as Tennessee Williams, the governments of Sweden and Denmark, Paul Newman, and Joanne Woodward (favorable). We’ve reprinted our full conversation with Vidal below.

Vidal

by Van Vooren

I have known Gore Vidal for several years. We are friends and had fun in Ravello, Venice, New York, Marrakesh, where we celebrated New Year’s Eve of 1969 (by the way, the cast of that party and the events of those few days could make a hilarious short story) and of course, Rome, where I had the privilege of being Gore’s house guest for a couple of weeks. Through him I met fascinating people including Tennessee Williams, Claire Bloom, Paul Newman, Joanne Woodward, Franco Zeferelli, to name just a few.

He has never ceased to intrigue me with his good looks, sharp comments and endless amusing anecdotes. His knowledge is phenomenal and his humor of such scope that I do not believe any subject is safe from his cutting wit.

We met at the Plaza a couple of weeks ago while Gore was in New York in conjunction with his new best seller, 1876. With his permission, I taped the following conversation.

MONIQUE VAN VOOREN: Of all the books that you’ve written, which one has been the most financially successful and why?

GORE VIDAL: 1876 because more people have bought it in hardcover than have bought any of the others.

VAN VOOREN: Do you think that people are more interested in historical events than they were previously or is it an awareness in the American public that wasn’t there before?

VIDAL: I think since Watergate they’re interested in what the past of this country was really like. Therefore they’ve turned to me because, at least in the two books, 1876 and Burr, I’m telling them the history of the country in a way they’ve never heard it told before and, presumably, they find what I have found interesting.

VAN VOOREN: Do you still have political ambitions?

VIDAL: I’d still like to be the President, of course, and I think the best way to do that would be to raise an army and seize the Capital. This strikes me as true democracy.

VAN VOOREN: In all truthfulness, would you consider entering politics?

VIDAL: The game is shut. It’s a game for cheerful, opportunistic lawyers who are hired by great corporations to become senators, governors, and presidents. If you’re not part of that club, as I certainly am not, you are not presidential.

VAN VOOREN: How long did it take to research Burr?

VIDAL: It seems like years. In Washington, D.C. there’s a character who is contemplating writing a life of Aaron Burr. I’d completely forgotten this until I reread the book. Washington, D.C. is the third volume of a trilogy that begins with Burr and goes on to 1876, all written out of order. Washington, D.C.. was the first one to be published but the last one in the chronology of the trilogy. So obviously Aaron Burr was on my mind at least since 1966.

VAN VOOREN: Do you have many people to help you in your research?

VIDAL: Nobody. But once I am finished Random House hires graduate students or, in the case of 1876, Professor Eric McKitrick of Columbia, who is perhaps the best authority on post-Reconstruction American history, to read every line to make sure there’re no errors.

VAN VOOREN: Are you Charlie, the reporter in Burr and in 1876?

VIDAL: “Madame Bovary, c’est moi“—that’s what writers usually say. All the characters are oneself and none of them is oneself.

VAN VOOREN: What is it about Italy or Europe that you find more enjoyable?

VIDAL: That it’s not America.

VAN VOOREN: But since you do make most of your money here in the United States, do you still enjoy the vitality and the tensions of the States?

VIDAL: Yes. After all, the United States is my subject, but as Hawthorne once wrote, “the United States are suited for many admirable purposes, but not to live in.” So I like the distance that Europe gives me. Also if I stayed here I’d be a full-time politician and have no time for writing, which is why I went to Europe to live in 1961. I’d never have written Julian if it hadn’t been for the sequestered life that I led in Rome and the classical library at the America Academy.

VAN VOOREN: I know you do get upset, and rightly so, about the politics over here but yet European governments are just as bad. Do you expect more of these governments?

VIDAL: I think that Europe has some of the best governments and some the worst in the world. I’d say that Holland, Sweden, and Denmark are all better countries politically than the United States. The average person is far better off in one of those countries than he is in the United States and poverty of the sort that we have is absolutely unknown in Northern Europe. In Southern Europe, we have, of course, very bad governments. There’s a wide range. We have a great deal to learn from Scandinavia and a great deal to be alarmed at from the Mediterranean.

VAN VOOREN: From your writing I assume that you’re not a religious person, yet you do have as friends an awful lot of very important clergy in Italy. How do you explain that?

VIDAL: I believe it’s my pastoral duty to convert them to atheism.

VAN VOOREN: Are you successful?

VIDAL: I believe that one by one they do drop from the Church.

VAN VOOREN: Where do you think America’s going? It seems there’s a swing to the right. People who were previously part of the labor and therefore so-called liberal are now the new breed of conservatives and the blue collar workers and civil servants are going for Reagan and President Ford. Can the Democrats beat President Ford and, if so, with whom?

VIDAL: I suppose it will be Humphrey and Kennedy. Then Humphrey will serve just one term and King Farouk will mount the throne, in which case, I might be tempted to play, if not Nasser, Naguibe. But it doesn’t actually make any difference whether the President is Republican or Democrat. The genius of the American ruling class is that it has been able to make the people think that they have had something to do with the electing of presidents for 200 years when they’ve had absolutely nothing to say about the candidates or the policies or the way the country is run. A very small group controls just about everything. Now the group is torn from inside. There’s the old money represented by Eastern families like the Rockefellers and then there’s the new, even crookeder money from the Southern Rim, as they call it, which is Florida, Arizona, Texas, and South Carolina. Nixon was a Southern Rim President, and so antipathetic to the old guard. The great struggle now is between Reagan, who represents the wheeler-dealers of the Southern Rim, and Ford, who represents the old money groups in the East. I expect Ford to beat Reagan and then in turn be defeated by super-Eastern money as represented by Humphrey and Kennedy.

VAN VOOREN: What is your opinion of American newspapers?

VIDAL: They’re all pretty bad. The Washington Post disturbs me the least because it knows what it’s doing and it’s well edited. Of the rich papers The New York Times is the worst in that hardly anybody can write English over there. Most of it reads like slight translations from the German. I wish they would let Canby write the whole paper. Politically, of course, it’s to the Right, but then the whole country is to the Right. The Times represents the country’s ownership as best it can and is rather horrified of the Southern Rim politicians like Nixon.

VAN VOOREN: In your far-fetched imagination do you think that Nixon has a chance to ever again enter politics in any war, shape or form in America?

VIDAL: No, but I think he thinks he has. The only solution to the Nixon problem is to go there to San Clemente in the daytime, find the box of earth where he lies, and drive a stake through his heart. Otherwise we’re all going to have to go around with garlic and silver crucifixes in case we come across him. The smell would be terrible.

VAN VOOREN: Do you think the Watergate scandal has hurt the Republicans for good, temporarily, or not at all?

VIDAL: Not at all. Heaven’s sakes, there’s only one party which I call the Property Party. It’s got two wings. One is called the “Republican” and one is called “Democratic.” It is the same party so it makes no difference whether a Democrat’s elected or a Republican’s elected. The ownership remains the same. Those who financed Humphrey in ’68 financed Nixon. All this has come to light during Watergate and since. It may well be they don’t want to call the party Republican anymore so they’ll call it the “True Blue American Party” or something like that and we’ll still have paid lawyers on the make running for office, doing what the people who give them the money ask them to do.

VAN VOOREN: What is your favorite book of all that you’ve written?

VIDAL: I think the two Breckinridges. Nobody else could have done them. I could imagine other people doing Burr or 1876 or Washington, D.C. but the Breckinridges didn’t exist before me and they will never die, ever.

VAN VOOREN: They call me “the true Myra Breckinridge.” I don’t know why.

VIDAL: Since there is no false one you have no choice but to be the true one.

VAN VOOREN: You’ve had famous feuds, one with…

VIDAL: I have never feuded with anyone. Others may have turned on me.

VAN VOOREN: I don’t know but I recall something with Mr. Buckley which was rather interesting and created quite a stir. Does criticism bother you?

VIDAL: No. At a very early age I decided that what I thought of others was a good deal more important than what they thought of me. Somebody has to keep score and I decided I was going to do it. I’m a born score-keeper and I realize, like an umpire, that my decisions may cause distress. I do my best to be honest and of level head. Occasionally I have to use an axe but only with regret.

VAN VOOREN: You mentioned at one point in an article that I read you eventually might like to give up writing and live the so-called “good life.” Were you just saying that for shock purposes or do you really mean it, because I can’t imagine a writer as prolific as you who would just give it up?

VIDAL: I can imagine giving it up very easily. I think when I said that my liver was a good deal stronger than it is now. The good life is out. I might become an ascetic, live in India. A little rice is about the best I can do now.

VAN VOOREN: What’s your opinion of Mr. Buckley?

VIDAL: Buckley? I never think about it. I suspect he is not as nice as he looks.

VAN VOOREN: You have known friendships with a number of beautiful ladies and in particular with Claire Bloom. What you think of Claire Bloom?

VIDAL: I think she’s a marvelous actress. She was the best Blanche Du Bois I ever saw and I’ve seen them all since Jessica Tandy played it originally. She’s very intelligent with a rather literary mind and I hope she plays the lead in 1876 should anybody dramatize it.

VAN VOOREN: What’s your opinion of Women’s Lib, if any?

VIDAL: Well, I’m all for it. I’ve written about that, “Women’s Liberation Meets Never Mailer Manson Man” was the title of the piece.

VAN VOOREN: What is your opinion of sexual encounters?

VIDAL: Which sexual encounters?

VAN VOOREN: Any one…

VIDAL: Any sexual encounter?

VAN VOOREN: Any sexual encounter that pleases you naturally, otherwise you wouldn’t encounter it…

VIDAL: Oh, that doesn’t follow. [laughs] There have been a lot of disasters along the way.

VAN VOOREN: Well that is an afterthought but I mean you don’t go into it thinking it’s going to be disastrous.

VIDAL: I’m in favor of sexual encounters.

VAN VOOREN: Do you think it’s durable?

VIDAL: No, nothing is durable, I think anybody who thinks sex is durable is going to have a lot of grief, Monique.

VAN VOOREN: On the basis of what do you think it cannot be durable?

VIDAL: First of all why should it be durable? Can you imagine having a love affair going on and on decade after decade? Macabre.

VAN VOOREN: What is to your mind, aside from you the best contemporary writer?

[Long silence]

VIDAL: The best novelist of my generation is an Italian living in Paris, still working and improving—Italo Calvino.

VAN VOOREN: What was his most well known work?

VIDAL: Cosmiocomics; there are about a dozen books. All translated.

VAN VOOREN: What made you choose Italy to live rather than France or Norway or Sweden which you seem to talk so highly about as far as the northern countries are concerned while Italy is a country which is as we talked about before filled with all kinds of social problems?

VIDAL: Well, it didn’t have all of those social problems when I moved there and Scandinavia is out because of the climate, as far as I’m concerned. I suppose my liking for Italy is partly atavism, my family are of the old Roman stock. They came from the Alps north of Venice. I liked Italy from the first time I went there in 1939, I was there in ’48 and ’49 and I was there again doing Ben Hur. I was always at home there, it’s a marvelous place to become invisible. Nobody bothers you and nobody is interested in you and I find that very good for work.

VAN VOOREN: What do you think of children?

VIDAL: What children?

VAN VOOREN: Any children…

VIDAL: I keep as far from them as possible. I don’t like the size of them; the scale is all wrong. The head tends to be too big for the bodies and the hands and feet are a disaster and they keep falling into things, and the nakedness of their bad character… You see we adults have learned how to disguise our terrible characters but a child… well, it’s like a grotesque drawing of us. They should be neither seen nor heard. And no one must make another one.

VAN VOOREN: You are obviously very cynical in a lot of your comments, are you really as cynical as you seem to be?

VIDAL: I don’t seem to be cynical to myself but how what I say goes down with others is their problem. I’m realistic. Come to me and show me a small cancer and I’ll tell you you’ve got a small cancer that should be cut out. That’s realism but in America it’s called cynicism. You’re supposed to say, ah, you’ve got a little beauty blemish here and I have some marvelous Max Factor that will hide it. That’s the American way of handling things. Anyway I’m a diagnostician not cosmetician.

VAN VOOREN: I see that you’ve been very kind to your dog.

VIDAL: Well, he’s all right, he can’t talk. He indicates an awful lot, however.

VAN VOOREN: You are obviously very aware that you are a good looking man and in some ways you’ve been called almost narcissistic about your looks, does age bother you?

VIDAL: Age bothers everybody. I was never narcissistic about my looks, but people thought that I should be so therefore I was. The whole point to American journalism is what ought to be true is true. Since I ought to be arrogant, impressed with my social position, overwhelmed by my beauty, therefore I am. Actually I was never my own type so I completely missed my beauty all through my youth. I have no social position and I stay away from what is known as society as much as possible. But people like to re-invent you, according to cliché. There are a lot of stores about me that really apply only to Capote or Mailer or somebody else. Everything is a mish mash.

VAN VOOREN: Have you seen Capote lately?

VIDAL: I’ve seen him about once in twenty years and I had an impression that the one time was probably too often. It was at Dru Heinz’s, I didn’t have my glasses on and I sat down on what I thought was a poof and it was Capote.

VAN VOOREN: What would you consider to be for you, the perfect day on all faces, including everything possible that you could have or do from the time you rise to the time you fall asleep?

VIDAL: Well, I would go on the Today Show, that’s how I would begin, and have half an hour with Barbara Walters and then I’d be driven down to Philadelphia to do the Mike Douglas Show, and then I’d come back and do my state of the union with David Susskind, ninety minute taping just the two of us, then I would somehow magically get out to California in time to tape Merv Griffin in the afternoon back to back with Johnny Carson. Then there come the late night shows in Chicago—a really good day, a well spent day.

VAN VOOREN: When you are in Italy how do you spend your time?

VIDAL: Well I have no television to go on so I get a lot of writing done. That’s my substitute for television.

VAN VOOREN: What time do you get up?

VIDAL: Whenever I wake up.

VAN VOOREN: Just when you wake up. You never get up before you wake up?

VIDAL: You have to have standards, Monique.

VAN VOOREN: Do you ever make love daily?

VIDAL: I used to yes but now I am catching up on my reading.

VAN VOOREN: At night what do you do when you’re in Rome?

VIDAL: Have dinner and go to bed and read.

VAN VOOREN: Do you go out to dinner with friends or do you stay home?

VIDAL: Usually I go out to the world of the trattorias, which is the pleasure of Rome.

VAN VOOREN: Who are your best friends in the world?

VIDAL: Oh, obscure people that you’ve never heard of—three, four, five, here there and everywhere.

VAN VOOREN: Yet your house in Ravello seems to always be, well always having important people visiting you.

VIDAL: No very seldom and I’m a much worse guest than I am a host, and I’m not an awfully good host either. I really like being there alone.

VAN VOOREN: What do you do all day long?

VIDAL: I work and there’s the garden and the gymnasium and the sauna and the day is very full there. Also if you go in for writing long complicated books like 1876 and Burr you’re going to have to spend an awful lot of time studying.

VAN VOOREN: What was your reason for calling Caligula—Gore Vidal’s Caligula?

VIDAL: A number of reasons aside from perfectly normal megalomania. For one thing, I didn’t want anybody to think it was Albert Camus’ Caligula. He seems now to be somewhat forgotten but you can never tell, he might have a revival. The dreaded Linda Wertmuller had threatened to do her Caligula when she discovered that we would not take her as the director for my Caligula, so there’s the chance that she might do one. So I thought it better to put my name in the title; something I learned from Fellini. When he began to make Satyricon four other Italian directors announced that they were making Satyricon, too. So he put his name in the title, which was something they couldn’t do or hadn’t thought to do. Can’t you see Rossi’s Fellini’s Satyricon?

VAN VOOREN: By the fact that you wrote the script for Caligula you were obviously well versed in that period of history since you have already done Julian. Did you have to do more research for Caligula?

VIDAL: No there are only two texts. There’s a Tacitus and Seutonius and once you’ve absorbed them then you’ve got everything anybody knows about the character.

VAN VOOREN: Where do you think the film is going to be made—entirely in Italy?

VIDAL: No, I think location stuff will be in Romania, Yugoslavia. We’re going to need a lot of people and it’s very expensive in Italy now, the crowds.

VAN VOOREN: What do you think of Paul Newman?

VIDAL: I just talked with him yesterday. He’s in Johnstown, Pennsylvania, making a movie about ice hockey. He’s an old friend, I’m very fond of him. He, Joanna and I all lived together in Malibu about 20 years before they were married.

VAN VOOREN: What is your favorite city in all of the world, not necessarily to live but to see?

VIDAL: I suppose it has to be Venice, there’s nothing like that.

VAN VOOREN: What is your next project after 1876?

VIDAL: Caligula and then I have two or three more books planned in my head but I haven’t done anything about them. Now I understand that Universal and NBC want to buy Washington, D.C. as a television serial and another network has come up with An Evening with Richard Nixon. I may just have to get justice for that one. The play was ahead of its time.

VAN VOOREN: Do you think that if that show was on Broadway today it would be a success?

VIDAL: I think it would have been a success at the time had we not come to New York. I am not much loved by the local press and Nixon of ’72 was a great hero.

VAN VOOREN: Wasn’t there some kind of interference at the time you were doing the show on the part of the FBI?

VIDAL: All sort of threats and peculiar shenanigans with the various people putting up the money.

VAN VOOREN: Are you a movie fan?

VIDAL: Yes! There are no bad movies, only bad audiences.

VAN VOOREN: Do you really believe that?

VIDAL: No! Just a good thing to say.

VAN VOOREN: What do you think of Seven Beauties by Lina Wetmuller?

VIDAL: I’ve not seen it. I’m saving that excitement for later.

VAN VOOREN: What do you think of John Simon?

VIDAL: Ah well, poor John Simon—what a nightmare, to wake up in the morning and realize that you are John Simon.

VAN VOOREN: Do you think he’s a good writer?

VIDAL: No.

VAN VOOREN: Do you think he’s accurate?

VIDAL: He’s irrelevant. He’s a peculiarly New York phenomenon. This is a place that worships incompetence particularly if it’s combined with energy and paranoid self-confidence. Only in a city like New York could Truman Capote have made it, or John Simon.

VAN VOOREN: What is the reason you don’t like Norman Mailer?

VIDAL: I don’t like what he stands for—

VAN VOOREN: Which is?

VIDAL: That women are put on earth only to provide men with sons—that’s a quote. He’s against masturbation, he’s against homosexuality. He believes that murder is essentially sexual. I think he’s rather an anthology of all the darkest American traits.

VAN VOOREN: What do you think of him as a writer?

VIDAL: He comes and goes. Sometimes he’s better than other times, like the rest of us.

VAN VOOREN: You’ve said that critics in New York were not favourable to you yet you consistently keep getting good reviews. I just read in The New York Times a review of your book 1876 and it was extremely favourable.

VIDAL: I suppose after 30 years I’ve worn them out.

VAN VOOREN: I think Seven Beauties you should see. I would like to hear your opinion of it.

VIDAL: I’ve only seen Love and Anarchy, which I thought was second rate. I don’t think I could take Giannini’s eyes in one more movie. He looks to the right. He looks straight ahead. He looks to the left. Then they get glassy, then he blinks them, then they get brighter.

VAN VOOREN: If you were making a movie of Julian who would you pick as Julian?

VIDAL: Albert Finney. And I think he’d like to do it too. He likes the book and I’ve talked to him about it.

VAN VOOREN: What do you think of Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor?

VIDAL: You’re just making me tired, Monique. I’ve had a rough day. To have those two vials of chloroform broken beneath my nose just before a party. I never want to hear their names again.

VAN VOOREN: Are you interested in her jewels and her luxurious life?

VIDAL: No.

VAN VOOREN: Do you think she deserves it?

VIDAL: I’m sure she deserves it, I just don’t want to heard about it anymore. I liked the trichotomy, that’s the only thing I ever liked.

VAN VOOREN: What do you think of Tennessee Williams?

VIDAL: Oh, I love Tennessee. Well you read my piece, didn’t you? Everything that I think about Tennesseee is in there. Practically everything—

VAN VOOREN: Some people may not have read that piece, can you say a few things about Tennessee?

VIDAL: Steal it from the piece.

VAN VOOREN: Can I?

VIDAL: Yes, take anything you want because I can’t say it any better than I wrote it.

VAN VOOREN: What do you think of Muriel Spark?

VIDAL: Muriel, well she’s very interested in her own work, I’ll say that.

VAN VOOREN: Did you like The Driver’s Seat?

VIDAL: I didn’t read it. Yes I did read it, I did like it, I didn’t see the movie.

VAN VOOREN: Besides writing which is obviously your life’s passion, what other passion do you have?

VIDAL: Appearing on television. I told you that! Monique, you didn’t listen.

VAN VOOREN: What other interests do you have besides reading and writing and of course, television?

VIDAL: I like looking at buildings and I like going into them sometimes and sometimes I like to stay outside of them.

VAN VOOREN: You said in some interview that I’ve seen and, of course, have told me that everybody was homosexual and some practice it and some don’t.

VIDAL: I never said any such thing Monique.

VAN VOOREN: You said something of the sort.

VIDAL: It’s like saying you’ve said you’re going to assassinate Gerald Ford, or something like that. What I said is that everybody is bisexual, and that is a fact of human nature. Some people practice both, and some practice one thing, and some people practice another thing and that is the way human beings are.

VAN VOOREN: How then can you say that they are bisexual if they practice only one thing?

VIDAL: Because you have the capacity to practice both and often given a certain situation, they can be persuaded, or persuade themselves to enlarge their scale. Kinsey figured it out. For example from 1 to 6 there is a small percentage that is exclusively homosexual, a small percentage heterosexual and there’s a wide band in the middle of people who respond to various stimuli. A little bit here, a little more there.

VAN VOOREN: It’s so funny I always thought of Nixon sleeping in a double bed yet you see him in twin beds.

VIDAL: Schizophrenics need two beds.

VAN VOOREN: Don’t you think that some people can be completely asexual?

VIDAL: I met one once but it’s very rare.

VAN VOOREN: I really don’t know if what you say that everyone is bisexual.

VIDAL: I am quoting from Freud. It’s not a theory, it’s a fact. It’s not a theory that everybody has two legs, two lobes to the brain which is why we tend to be interested in symmetry, always balancing things. To have an interest in both sexes is equally normal. Whether it’s practiced or not is something else again. Some do. Some don’t.

VAN VOOREN: You have never made it a hidden fact that you are rich and bisexual.

VIDAL: I have never said anything about either. Other people say these things about me. What ought to be true is true, and therefore he said it.

VAN VOOREN: Do you deny it?

VIDAL: I don’t deny or affirm anything. I’m not very personal.

VAN VOOREN: But I’m going to ask you are you bisexual and rich?

VIDAL: Everybody’s bisexual as I finished telling you. I did not say that everybody was rich, however.

VAN VOOREN: What do you plan to do with the money you obviously are going to make and make and make as long as you continue writing?

VIDAL: I give 50% to the United States government and the rest just vanishes as money tends to do.

VAN VOOREN: What is the best play you have ever seen outside of The Best Man, of course?

VIDAL: Well you’re narrowing the field. I don’t much like plays.

VAN VOOREN: What is your favorite movie?

VIDAL: Marriage is a Private Affair with Lana Turner written by Tennessee Williams from the ’40’s. Myra Breckenridge admired it tremendously.

VAN VOOREN: Why didn’t you see the movie Myra Breckenridge?

VIDAL: Because I read the script.

VAN VOOREN: Do you think this film will come back?

VIDAL: If it comes back I go away.

VAN VOOREN: It’s actually a movie that could be done over again.

VIDAL: It was never done. I’d always hoped that we might do Myron with our friend Mick Jagger. Not only would he play Myra Breckenridge and Myron but also Maria Montez.

VAN VOOREN: What would your advice be to upcoming writers who look to you as the utmost in your field?

VIDAL: There is room at the top for only one. STAY AWAY!!

THIS INTERVIEW ORIGINALLY APPEARED IN THE APRIL 1976 ISSUE OF INTERVIEW.

For more New Again click here.