The Russian Prince

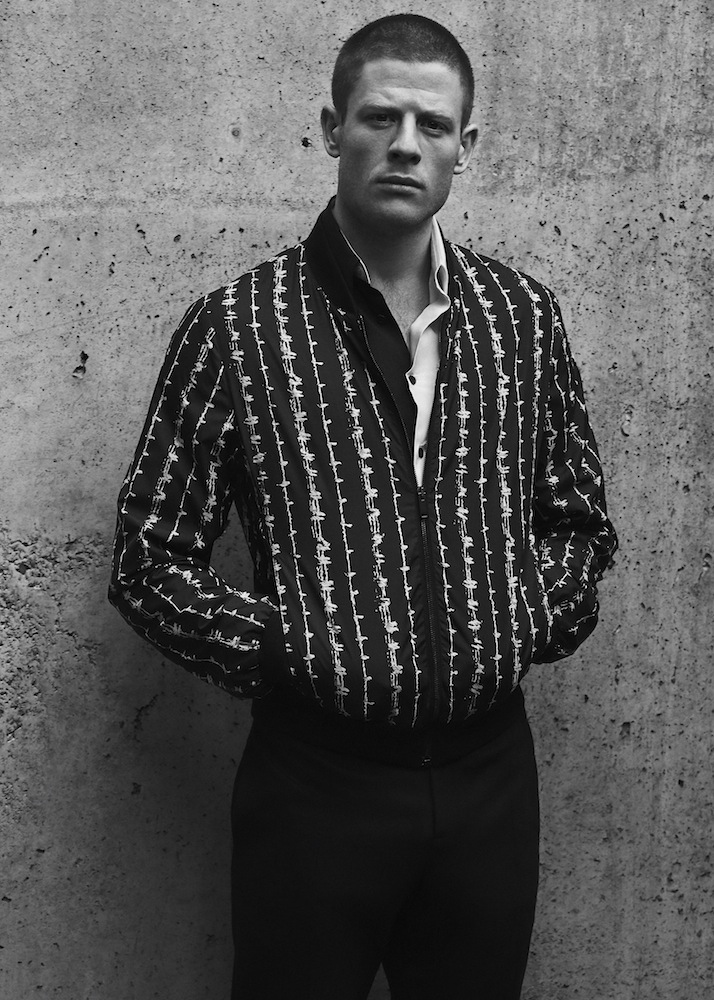

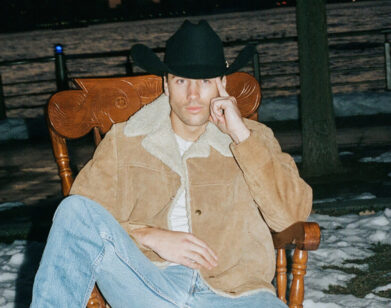

JAMES NORTON IN LONDON, DECEMBER 2015. PHOTOS: MARK RABADAN. STYLING: FANNIE AKERBLOM. GROOMING: VERO MARTINEZ.

“I was standing on a Lithuanian battlefield with 300 Lithuanian-Russian extras behind me,” recalls British actor James Norton. “I was able to pull my sabre out of my scabbard and say, ‘Charge!’ Little eight-year-old James was having the time of his life.”

Norton is talking about his latest project, a six-part adaptation of Tolstoy’s epic novel War & Peace. Directed by Tom Harper from a script penned by Andrew Davies, and co-produced by the Weinstein Company and BBC, the miniseries features over 90 speaking roles and plenty of famous faces. Cinderella actress Lily James stars as the animated heroine Natasha Rostova, with Paul Dano as her bumbling suitor Pierre Bezukhov, Aneurin Barnard as her ambitious cousin Boris Drubetskoy, Callum Turner and Tuppence Middleton as the debauched Kuragin siblings, Brian Cox as the famous Russian general Mikhail Kutuzov, and Gillian Anderson as the society hostess Anna Pavlovna Scherer. Norton plays Prince Andrei Bolkonsky, Tolstoy’s distant hero and a man who wants for nothing, yet remains perpetually dissatisfied.

“Andrew described Andrei as the ‘the Russian Darcy,’ and although I rolled my eyes and was like, ‘Thanks a lot, Andrew,’ because obviously it had been picked up by lots of press, it’s true,” says Norton. “There is something very intriguing and enigmatic about both of them, whilst appearing to be really cruel and callous towards their loved ones,” he continues. “Everyone’s drawn to Andrei.”

Educated at Cambridge and RADA, Norton seems like an obvious choice for a “Russian Darcy.” He’s appeared in period dramas before and currently stars as the vicar-turned-sleuth Sidney Chambers in the PBS series Grantchester. But Norton is not one to be typecast. The 31-year-old received a BAFTA nomination for his chilling performance as Tommy Lee Royce, a rapist and murderer recently released from prison, in the BBC’s gritty, Yorkshire-set drama Happy Valley. In addition to War & Peace, he’ll return as both Royce and Chambers later this year.

EMMA BROWN: How did you get involved in War & Peace?

JAMES NORTON: I got involved quite late on, actually. I hadn’t read the book. It was quite a daunting prospect; there are many who have strong relations to the book, particularly Andrei. [Upon reading it,] you realize how extraordinary and special, how deserving it is of its status. With the people involved and Andrew Davies’s script and the locations, as soon as we realized what it was, of course, we did absolutely everything we could to try and make it happen. Then it did and it was about trying to understand Andrei and get to this extraordinary character because again people, particularly the Russians, have a real relationship with him. They really treasure and respect the characters. I had this amazing moment in Russia where I bumped into this guy called Lev Dodin, he’s a theater director for the Maly Theatre Company, and I went to see his Cherry Orchard and he summoned me backstage at the interval. He didn’t speak a word of English, but he had a translator and he said, “I want to meet the man playing Bolkonsky.” And I thought, “Gosh, that’s a bit scary.” This immaculately dressed little man turns up and he said, “How old are you?” I said, “I’m 30,” and he goes, “Good age for the Bolkonsky. No man has ever played Bolkonsky younger than 40, because the spheres and circles of contemplation are so complex that at your age, no man has dared to take the part.” And then only thing he could say in English was, “Hey, hey, James. Good luck.” So there was this real sense of imparting this responsibility on me: “You’re welcome to try, but don’t fuck it up.”

BROWN: Did you have to audition for Andrei or did they approach you and make you an offer?

NORTON: I auditioned a long, long time before and then, as it often does, things went quiet. Then in November, I had a conversation with Tom [Harper] and put a couple of auditions on tape. You know there’s interest when they start to come back with little pieces of direction, and then I knew things were getting really serious when I got a call on a Tuesday night from my agent at about eight o’clock saying, “Umm…not to freak you out, but Harvey Weinstein’s in town and he wants to meet you tomorrow at 8:00 AM in his hotel for breakfast.” I was like, “Oh my god,” because I’d never met Harvey before. Then I met Harvey, and I met some of his execs, and it went from there—after a very shaky cappuccino with Mr. Weinstein.

BROWN: I was going to ask, what do you order when you have breakfast with Harvey Weinstein?

NORTON: I didn’t eat. Put it that way. I think I managed a slurp of my coffee and that’s about it. I’ve actually met him many times since and he’s a great guy. He came on set for a bit and he’s been very supportive. I think, hopefully, they’re really pleased with the outcome, because it was quite a new venture for them embarking on U.K., BBC-based television. So we were very lucky to have them. Having done a couple of BBC dramas, I think we were all aware of the support we had in the Weinstein Company, not as much the financial backing, but just that extra bit of clout. I think it meant when they decided, “We need to film in Russia. We need to be on that frozen lake or in that beautiful palace and it can’t be anywhere else,” it gave them the boost to take the plunge. And it made such a difference being there. I can’t tell you. Being in Russia filming War & Peace…filming War & Peace alone is an extraordinary experience, but to be out there was just magical.

BROWN: When they gave you notes during the audition process, what did they tell you to do differently?

NORTON: It was all about finding his darkness. As an actor, I think most people have a tendency to want to demonstrate that they can act, they can emote. The challenge of Andrei was to keep it incredibly contained, and not do very much, but at the same time communicate this darkness and this cynicism. There’s so much going on in Andrei. He’s wrangling with these big existential conundrums, and he tries out different routes to fulfillment. He tries falling in love, that doesn’t work. He goes to war and searches for military glory, that doesn’t work. He does the quiet life of a farmer. He’s always active. That’s what I loved about him, he’s always looking, searching. He’s really inquisitive. Those are the best parts to play, especially as a young, 30-year-old guy also trying to work it all out. It’s a wonderful headspace to wrangle with for six months. But despite all this, he’s also very Russian in his lack of emotion. So it was trying to show all that stuff was going on and that brooding, but at the same time hardly doing anything at all. That was the note I got: remember the darkness, but don’t do anything. When I came to set—because I’m quite a smiley guy, I have my moments, but I think I’m generally of a relatively optimistic nature—Tom kept shouting, “James, stop smiling! Stop smiling.” I wasn’t allowed any hint of a smile, apart from maybe twice in the whole six months.

BROWN: Did that affect your mood off set?

NORTON: No. It was nerve-wracking as an actor. I often gave them a lot of choices in the takes. You give them some that are a little bit more demonstrative and some that are so contained. Having seen the first episode, they generally went in for the more contained. So that’s quite nerve-wracking—”Am I communicating all this?” You really try to work the character out and spend time in the headspace of the character. That’s what I did. I do really mundane, everyday things, but in the headspace of the character. Having spent all that time, you do want the audience to go on that journey with you. But off set, I’m not the kind of actor who spends all his time wallowing in his hotel room. We had an amazing time. There were moments when it became a bit of a party, especially when we were all out in Saint Petersburg together. It was magical. Lots of fun nights out because we were all very over excited.

BROWN: Did people in Saint Petersburg know what you were doing?

NORTON: They did. The first day, we covered the equivalent of Trafalgar Square or Times Square in snow, and they gave us free reign over their Buckingham Palace. So they were aware of us being there, and incredibly generous with these extraordinary historical sites. We blocked off loads of the roads. It was really warming. It was a weird time to be in Russia with the political situation going on in the Ukraine. Filming in Lithuania and Latvia, there’s a certain awareness of what’s going on. I think we all went out going, “What’s it going to be like?” And the Russians were so welcoming. Brilliant crews. The Lithuanian crews were absolutely incredible as well, incredible tailors. All our costumes were handmade. But the Russians were all really accommodating, and that made it really special. To be allowed in Catherine’s Summer Palace…Lily and I have this scene where we fall in love and we waltz up and down this enormous gold hall with thousands of candles and a live orchestra and 300 Russian extras. To do those scenes in situ really meant it was a once-in-a-lifetime job. I hope that that really lifts the project and gives it that special touch. It’s an amazing place, Saint Petersburg. It’s like a big, old butch Venice. It’s like no place I’d ever been.

BROWN: Did people shout “Bolkonsky” at you in the street and buy you drinks?

NORTON: No, no. They didn’t know who I was playing. We had the sideburns, so we were slightly conspicuous—we looked like we were in some sort of Andrew Davies adaptation. We had some fun. The shoot was bookended by these stints in Saint Petersburg. We started in minus 20, snow up to your waist, mid-winter, brutal cold. And then we ended in June in the white nights when it didn’t get dark. Being there at the beginning and the end with everyone together was really special. The end was sort of sentimental and exciting, and the beginning was all meeting each other and equally exciting.

BROWN: I know you were already friends with Lily James. Did you know any of the other cast members?

NORTON: Lily and I have been friends for some time. We’re good friends. I knew quite a few people, actually. I knew Aneurin Barnard, who plays Boris. Because there were 95 speaking roles, there was a constant stream of amazing actors coming in. Nick Brimble, a friend of mine who I worked with on Grantchester, came out for one scene. The depths of talent, how the casting department had managed to get together these really illustrious actors, was a dream. Every day, every scene, you were like, “My god. I’m doing a scene with Brian Cox today and then I’m onto a scene with Stephen Rea.” For us young actors, I think we were all very, very star-struck and impressed by the caliber of everyone who came out.

What was really challenging for everyone was that we didn’t shoot chronologically; we shot everything all at once. Weeks in Saint Petersburg had to cover seven years of Russian winter. So by definition, we never had a sense of chronology. One day you might be in Saint Petersburg in 1806 and then Moscow in 1812, and then you might jump back to Saint Petersburg. It was completely discombobulating and an incredible credit to Tom Harper, the director, who kept us grounded, and this amazing woman called Marnie [Paxton], who was on continuity. We were constantly shouting, “Marnie, where am I? Which year is it?” And she was always on script to keep you orientated. That, I think, was one of the bigger challenges we faced—keeping a sense of the arc of each character.

BROWN: It’s quite sad, but there are so many characters that I have to read it with the Wikipedia page open so I can remember which is which. Helene Kuragina and Julie Karagina…

NORTON: I know. I don’t what page you’re on, but I really recommend persevering. Once you’ve got the 20 main principles down and you’ve got their faces in your head formed and established, it becomes a really great, easy page-turner. Apart from the massive chunks of philosophy and military tactics, where he goes a bit wayward and you’re allowed to skim-read a bit. But the story itself, we described it as a soap opera because it’s just got loads of young people falling in and out of love and having duels and getting drunk and having sex and revenge. When he starts ruminating on military tactics, you’re like, “I do not care whether this weird general went and outflanked that other weird general.” But there are these amazing moments for Andrei and Nikolai [during the war], and to film those was so fun. There were months when we shot basically all of the war stuff, and nearly all the female characters went back to London, and it suddenly became a little bit of a sports tour. All the boys came back at the end of the day: “Ah, did you see that bit where I did that!” It was kind of funny. And then the girls came back and we all had cuts and bruises and they rolled their eyes at our ridiculous stories. But it’s a tough read, some of the military techniques. It’s fun to be part of that smug club: “I’ve read War and Peace,” but I obviously have a massive incentive.

BROWN: You came into the offices a few years ago, and you talked about how you felt you really had to like the characters you played and people would always give you funny looks when you said that, because your character in Happy Valley is not particularly likeable. Do you still feel that way?

NORTON: I do. It’s a dodgy area, because if you start to say that you “like” Tommy Lee Royce from Happy Valley, a lot of people will rightfully put you on trial: “What on earth do you mean by that?” I think it’s about empathy. It’s about knowing the reasons why a character does certain things and thinks certain ways. If you’re constantly stepping outside of the character and judging them, you’ll never really be able to fully engage because you’ll always be slightly cynical. I think to be in that moment as much as you can, you have to fully empathize with them and it is about liking them and feeling their pain. Andrei was a much, much easier character to like and empathize with than Tommy, but he’s objectively, he’s not likeable. Particularly the beginning of the story, he’s really cruel to Lise his wife and his family. He’s so aloof and so cut off from everyone emotionally that you would be forgiven for thinking he’s a prick. But then of course as the book goes on and as our adaptation goes on, you start to realize that he ultimately does mean well and he does have faith in humanity, which is the most important thing, I think. He believes he sees good in people, and he sees good in himself, he’s just finding it difficult to discover that goodness and that calm. I really, really enjoyed the journey to empathizing with Andrei, and trying to work out why this man is so disgruntled. As Pierre says in one of our early scenes, “You have everything going for you. You could do anything and everyone looks up to and respects you.” And Andrei just sighs, “Yeah…so they say.” Immediately that conflict is set up: the aristocrat who’s going to inherit this fortune and has got this incredible military career ahead of him and is very intelligent and women find him very attractive, he’s got all that going for him and then he seems to be so pissed off with his lot. That conflict is brilliant drama. For some reason, he is incredibly compelling and you are drawn to him. Everyone wants to know what on earth is going on. It goes back to what we were talking about earlier—having such a cold, callous exterior but then showing the audience and all the other characters that behind the eyes there’s a lot going on and drawing people in and hopefully they want to know what that is. But he’s a bastard to Lise. The scene when he goes to war and leaves her heavily pregnant with his father is brutal—physically pushing her down into a chair while she’s sobbing her eyes out. It was quite a harsh scene to shoot as well.

BROWN: Did you find that relationship particularly challenging?

NORTON: Yeah. Again, it’s a bit like what we were saying before about liking and empathizing with characters, particularly when their moral choices are so different from your own. Then the challenge is to try and understand why they’ve done what they’ve done. But that is difficult because at that point in the story, you meet Andrei and he is so disillusioned by his life, to the point that he’s willing to ride off to battle and when Schöngrabern happens and one of the commanders offers his services to divert the French army, Andrei goes straight up to him and says, “I’ll go with you,” which is essentially suicide. For a young man with a baby on the way, what’s going on in there? So that was hard, to try and find that darkness without the three chapters of working out. There were a lot of conversations with Tom when we were doing our rehearsals about where Andrei’s disillusionment had come from.

WAR & PEACE PREMIERES MONDAY, JANUARY 18, ON LIFETIME, THE HISTORY CHANNEL, AND A&E.