James Cauty’s Traveling Dystopia

When planning this year’s Glastonbury Festival, a representative told artist James “Jimmy” Cauty, “I’m going to get the Royal Air Force to helicopter it into Glastonbury. I’m going to get a Chinook and the photo of it being brought in will be on the front cover of The Times.” The item of the representative’s interest was Cauty’s Aftermath Dislocation Principle (ADP) installation, which became a standout piece at Banksy’s Dismaland. Over the course of the past year, ADP evolved from a series of small models of rioters in jam jars into a 40-foot-long replica of a suburban town saturated with police and television crews in the moments after a city-wide riot. Now, it has evolved yet again to comprise three distinct 1:87 scale models housed in shipping containers: One creates the ravaged town of Old Bedford, another depicts a monolithic structure titled New Bedford Rising, and the third is a bridge hypothetically meant to connect the other two.

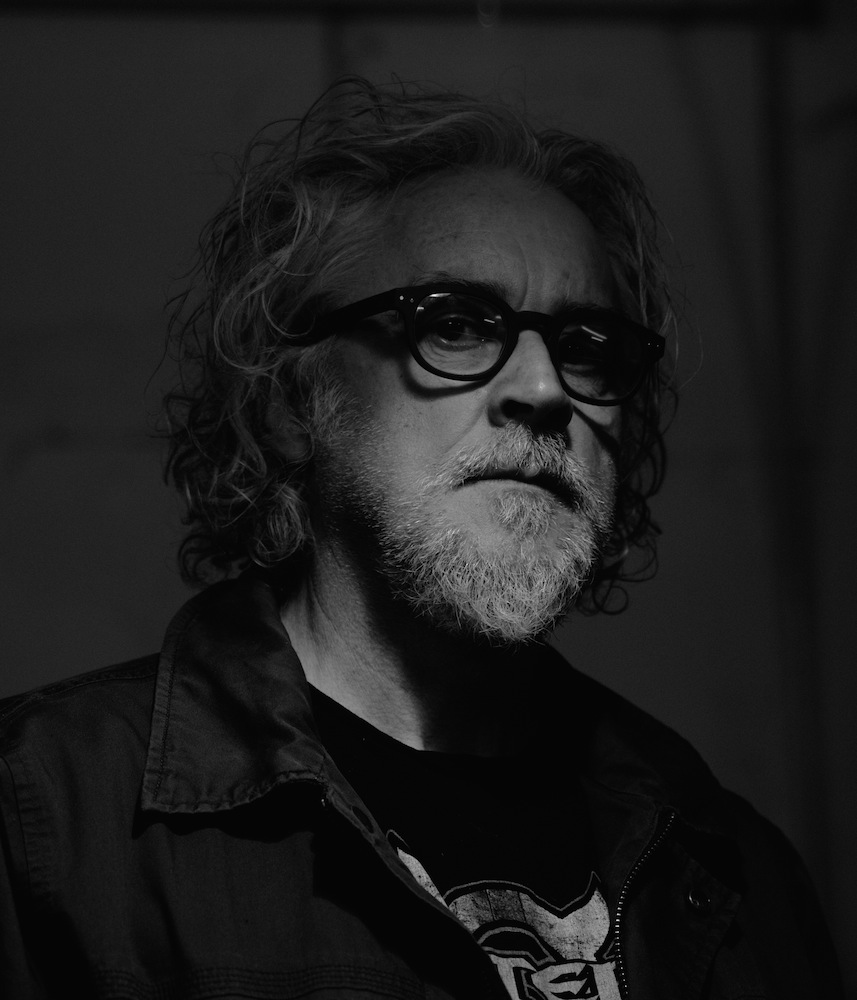

This summer, New Bedford Rising will appear at Glastonbury and the shipping container holding the bridge is on view at the Royal Academy. From now until Christmas Day, the largest ADP crate, containing the dystopian vision of Old Bedford, is making a 38-date tour of the U.K.. Just after the tour began, we meet Cauty under a dank railway arch in London, south of the River Thames, where he’d been preparing the pieces. The artist—who also co-founded rave pioneers The KLF with Bill Drummond—has a mischievous glint in his eye, is softly spoken and affable, but isn’t entirely convinced the Royal Air Force will agree to deliver his work to Glastonbury.

“Years ago, Glastonbury asked The KLF to play and I said that we would but only from a Chinook, with a sound system underneath,” he says, reflecting on his previous experience with the festival. “They agreed to it but the Civil Aviation Authority was just like, ‘Forget it. You are not doing anything like that, ever. Especially over thousands of kids.'”

JOSH JONES: Aren’t you contractually obliged to not talk about The KLF?

JAMES CAUTY: No, it’s actually The K Foundation, specifically the money [Cauty and Drummond’s K Foundation famously burned £1 million cash in an art action]. We signed a contract with ourselves that we wouldn’t talk about it. It’s a 23-year moratorium, which actually ends next year. All that stuff is pre-internet so it’s pre-history as far as I’m concerned. It’s almost as if it never happened.

JONES: So if you talk about it do you have to sue yourself?

CAUTY: Nobody gets sued. I’d get a look from Bill saying, “I told you not to mention it.” I feel bad even saying this because you’re recording it. It ends next year and there’s a guy making an unsanctioned documentary about The KLF who keeps trying to get people to come down to the ADP tour to get photos and footage. It’s making me really jumpy at the moment; I don’t like having lots of photos of me out there.

JONES: When ADP was at Dismaland, people could walk around the whole thing. Now you’ve put it in a shipping container.

CAUTY: It was always meant to be seen in a room. At Dismaland they walked around and stole stuff off it, so afterward we showed it in arches in London, put boards around the whole thing, and drilled holes to look through. I think that was the best it’s been. I had to cut quite a lot off to get it in the container. The model was 8-feet wide and the container is 7-feet, 6-inches wide.

JONES: Did you ever slip into the crowd at Dismaland and listen to what they had to say?

CAUTY: I’ve overheard people talking about it and it seems to be universally liked. I haven’t had many dissenters – obviously there are some, but I don’t think I’ve ever made anything that’s been liked by so many people. I guess with the band, everybody liked the music. It’s weird when you do something popular because you think you could never, ever follow it up with anything again. At the moment I’m not even trying to think of anything.

JONES: Do you prefer the way people interact with the piece now that it’s in a container?

CAUTY: I really miss some things about the old version quite badly, like being able to see the edge. In a way it was all about the edge and the little people coming up and looking over but now that edge is right up against the piece of metal so you lose that and you lose the spectacle of walking into the room and seeing all the flashing blue police lights. On the whole I’m happier with it. People seem to love looking through the holes. They make up their own narrative. It was very tricky to work out where to put the holes in the container; the container was half a mile away from the workshop so we’d have to measure the distances from interesting things very precisely and then run to the container and try and remember if it was to the left or right of the thing we were drilling by. There are a few instances where you look through the hole and there’s absolutely nothing there; you’ll be looking at a brick wall. There are other little things, though, that have occurred, which I would never have predicted. There’s one view where you’re looking through a forest and you can see a couple of policemen in the distance. You could never have known that you’d get that in advance. There’s a lot of luck involved.

JONES: You’ve just let this evolve. It started off with a riot in a jam jar and now look at it.

CAUTY: I’m just running along behind trying to keep up with it. It does have a life of its own. I’m sort of in charge, but not really.

JONES: Is that how you work with everything?

CAUTY: You have to let ideas run wild and follow them. I definitely don’t chase after the money; we still haven’t really figured that one out. It’s free to view and mostly in community centers, in places where they don’t have any funding, so we’re paying to do the tour. It’s something like £65,000 worth of haulage, which we’re trying to pay for by selling t-shirts, postcards, posters and rioter jam jars. It’s hard to get people to part with their money, especially when they’re in a poorer area.

JONES: You bought all the figures from a German model-maker. Have you bought him out yet?

CAUTY: They won’t play ball, these German people. I don’t know how many times we’ve tried contacting them. I’ve even written letters to them in German saying, “I’m buying thousands of these people through a normal shop, why can’t I buy them directly through you?” and they won’t reply. It’s this little family-run, Bavarian business. They’re also discontinuing the policeman model whose heads I use, so there’s going to be a black market on them—I’ll be trying to buy back the models that got stolen from Dismaland on eBay!

JONES: How did you select the places to visit for the tour?

CAUTY: We just had a map on the wall, some pins, and a meeting. We started looking at towns and choosing the ones that we liked. All of the places have some kind of unrest in them, [but] pretty much everywhere in the U.K. has some kind of history, so it wasn’t hard to find. I said we could go back 1,000 years and there was no need to go back that far; 100 years was plenty.

JONES: Not all of them are towns, though, are they?

CAUTY: I wanted to make sure to do the Battle of the Beanfield, which isn’t really a town but was a famous hippy riot with the police near Stonehenge. We managed to secure this place called the Dinky Diner, which is an abandoned roadside American diner. It’s 10 miles from Stonehenge, but it’s next to the entrance to the field where the riot was.

JONES: What’s the history of the Beanfield?

CAUTY: It was the Peace Convoy, which was a load of New Age travelers. Every summer they would try to go to Stonehenge. Nobody knew why; they were attracted by some spiritual reason—I was the same, I used to go when I was a teenager. Every year the police would say we weren’t allowed to go. This one particular time, in 1985, the police got them to drive down a country road, then stopped them and started beating everybody up, including the women and the children. The convoy drove into a bean field and the police followed them in. They’re driving in circles because as soon as they stopped, the police beat the shit out of them. It was a really bad bit of brutality. I’ve seen quite a few bits of rioting, but there’s a really shocking bit of footage online. It was horrible.

JONES: After the Beanfield, you’re coming to London. You have a lot of places to choose from here…

CAUTY: We’re doing Tottenham and Brixton, as well as Hackney and Croydon, right down in the south of the city. I’d like to get it on the site of all the burnt out shops from the 2011 riots, which are still there, just with fences round them. We’ll be in each place for a week or so.

[The tour] ends in Bedford on Christmas day. Have I told you about the Panacea Society? They believe that Bedford is the original Garden of Eden. Seriously. I originally said that the ADP was based in Bedford, and I chose that purely randomly. This guy came to see it, wrote about it on his blog, and mentioned the Panacea Society. In the end he put us in touch with them and, although they don’t really exist anymore as a religious group, but they’ve still got a charity. They do the utopian thing, we’re doing the dystopian thing, and they’re going to host us. The weirdest thing is that when Jesus comes back, they’ve bought him a house to move into. It’s on Albany Road and is furnished and ready for him. I haven’t seen it, but I’d imagine it’s your usual suburban house. There’s no one living in it; it’s got a museum in it and is only open on certain dates during the year. It’s all a bit weird, [but] it’s great. So we’ve hooked up with these people and all three containers will converge there on the 23rd December.

JONES: Do you have a favorite riot?

CAUTY: I’m not a fan of riots. I’ve been on the periphery of them but I’ve never gotten involved. I’m an observer of things like that. What I’ve observed with rioting situations is that there’s obviously a group of kids who like fighting, but there’s also a group of police who like fighting as well. Once those two groups meet, I don’t want to be around. I haven’t actually been involved with a running battle with the police. When I owned armored personnel carriers there were two stand offs with the police, but it never got to a point where we were in a fight, usually because I was inside and safe. Now I’m an armchair revolutionist. I quite like all the looting for the hell of it as a spectacle. To see kids running off with trainers and color televisions, kids with so many color televisions that they have to dump some beside the road because they can’t carry all of them—that I find quite amusing. It’s completely senseless but I like that in a way. You can understand why people would want to do that, especially the younger people: We’ve created a world where they can’t have any of the things they’re supposed to want. I know that I’m kind of the go-to artist now for anything riot-based, but I’m not that into it. I’m not really that into model making either. It’s funny how you can get into these areas quite by accident.

JONES: There goes all of my questions then…

CAUTY: I had a worse problem when I did the Lord of the Rings poster in the ’70s [Cauty, at age 17, was the artist behind a Lord of the Rings poster sold in the U.K. chain store Athena]. As soon as I’d done it, punk rock happened and I had to deny any knowledge of my work. People would ask if I was that hippy that had made that wildly successful poster and I’d say no. It was the second most sold poster in its history, behind the girl playing tennis with no knickers on.I was right out there with the tennis girl. It was just me and her through the end the ’70s and into the early ’80s. It’s only now that I can admit I did that. When you’re younger you’re more tribal, those things matter.

JONES: Do you consider yourself an artist?

CAUTY: Yeah, I might as well be. I’ve tried calling it other things, like “maker,” but it didn’t work. I didn’t like “artist” because it sounded a bit pretentious but it was always on my passport that I was an artist. I’ve got something in the Royal Academy now, which is amazing—I know Richard Wilson, the guy who did the oil slick at the Saatchi Gallery, and invited him to see the ADP, which he thought was fantastic. He’s curating the summer exhibition at the Royal Academy and asked if I would show one of my riot jam jars. When the form came through I had to fill out a bit describing the work and I put in “shipping container” instead of “jam jar.”

It is a bit out of my realm, though, to have a show in an institution like that. I don’t have any art training or anything. It was interesting delivering the work there, because normally you’re told to stick it in a corner and they’ll deal with it later. At the Royal Academy there must have been at least 30 people, with gloves on, involved in getting the container off the lorry and into the building. I hadn’t really experienced that level of care before.

JONES: Is recognition from the art world something you’ve aspired to?

CAUTY: No, not really, but it turns out that even if you say you don’t want that, you actually do. Your stance could be that you’re an outsider and that you don’t care, but you secretly do. You do it for yourself but want your peers to acknowledge that they get something from what you do. You want people to say that they got something from it and it made them do something else. You want the recognition that what you do is relevant or affecting things.

JIMMY CAUTY’S ADP TOUR WILL BE VISITING SITES IN LONDON, STARTING TOMROROW AT STYX IN TOTTEHNAM, UNTIL JULY 1. FOR FULL INFORMATION, CLICK HERE.