The Eternal Travelogue: Henri Cartier-Bresson at MoMA

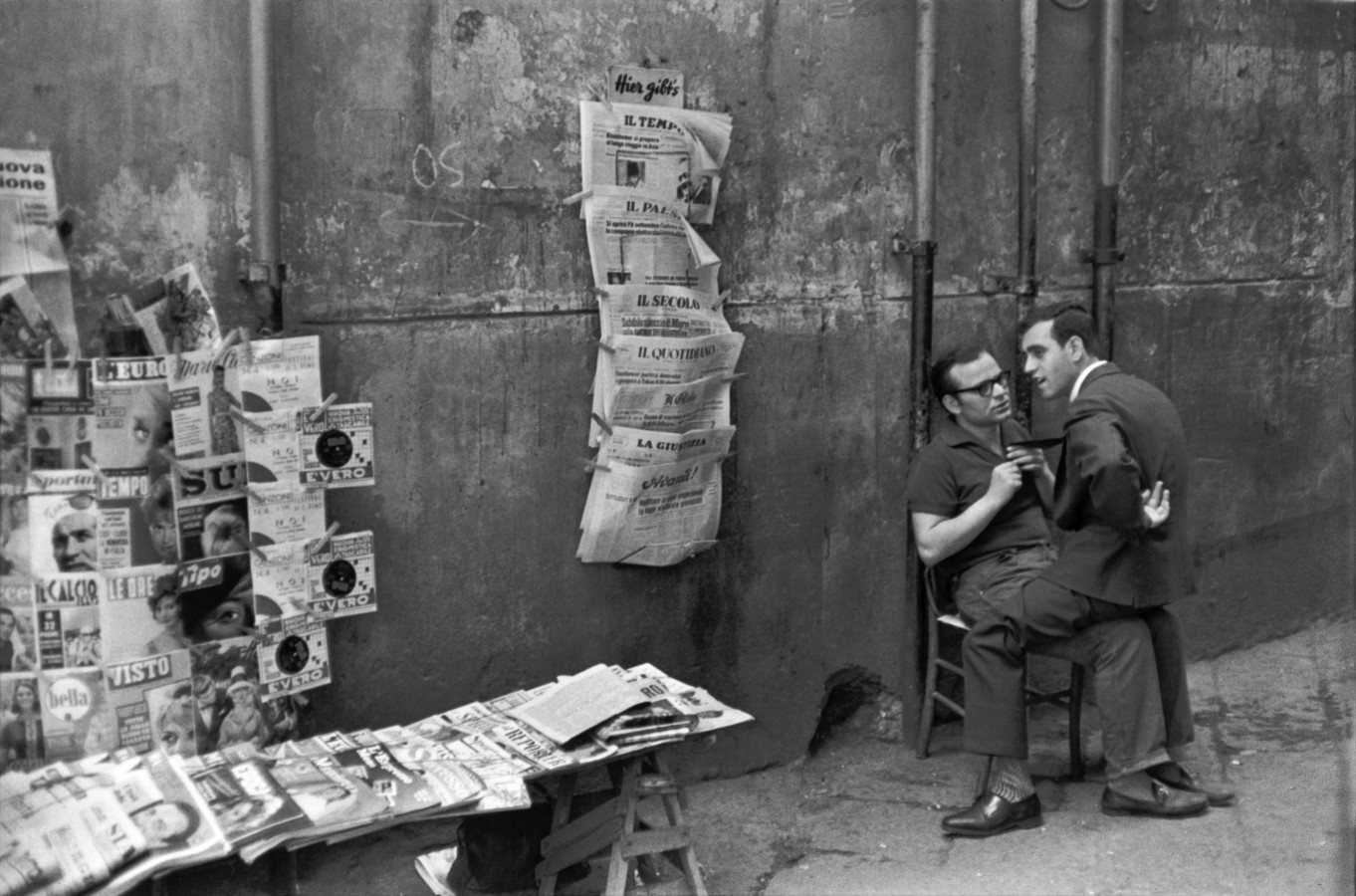

UNTITLED, 1960. COURTESY MUSEUM OF MODERN ART

Insired by a photograph in the 1931 volume of Arts et Métiers Graphiques, Henri Cartier-Bresson armed himself with a Leica and hopped across the ocean in search of “eternity in a moment.” Eternity, decades of subsequent work would reveal, involves a prolonged travelogue documenting war and hazard with a luxurious sense of beauty and a calm appreciation of local community. “Henri Cartier-Bresson: The Modern Century” at the Museum of Modern Art is the first US retrospective of Cartier-Bresson’s oeuvre in 30 years and captures the spirit of his work through nearly 300 photographs spanning five decades.

A major proponent of photojournalism and a co-founder of Magnum Photos, originally a cooperative conferring legal rights to photographers, Cartier-Bresson would capture Europe as the carrier of Western Civilization was assessing its self-worth. Colonialism and the Empire mindset was still in the air: one of the most resonant of Cartier-Bresson’s images depicts a group of Muslim women praying at sunrise, appearing motionless like statues despite violence nearby (Srinagar, Kashmir, 1948). A section of the show called “Modern Times” alternates images of leisure with those of work and innovation, with juxapositions like a photograph of a couple admiring furniture at the Galeries Lafayette and an image of a man on the street seeking work (Hamburg, Germany, 1952-53).

Beginning in the 1940s, Cartier-Bresson’s images appeared on the pages of popular magazines such as Paris Match and Life. Despite relative mobility, the photographer often worked under an authoritarian eye, as in his four-month-long documentation of Mao Tse-tung’s agenda for industrialization (The Great Leap Forward, China, 1958).

A certain felicitous imperfection runs throughout Cartier-Bresson’s work, due perhaps to attending surrealist meetings with a painting student at the Lhote Academy in Paris and exposure to photographers such as André Kertész and Man Ray. Chance and salient intuition contribute an unspoken eloquence and poignancy, most unforgettably in the image of a man and his reflection blurred mid-jump in Behind the Gare Saint-Lazare (1932). In the epigraph of his 1952 monograph, The Decisive Moment (Images à la sauvette), he quotes Cardinal de Retz: “There is nothing in this world that does not have a decisive moment.” The interplay of light and shade; line, space and blur; spontaneity and order reveal his acuity towards capturing the “decisive moment,” from his work as the first Western photographer to be admitted to the Soviet Union after Stalin’s death to everyday life viewed from a Parisian street.

As with his photographs of Gandhi the day prior to his assassination, Cartier-Bresson’s portraits were neither staged nor wholly anticipated. A selection of 34 portraits includes Matisse surrounded by his doves and Giacometti sculpting behind a thin veil of cigarette smoke. Cartier-Bresson preferred to photograph his nearly 1,000 subjects for portraits in their homes. The air of comfort can be heavy, but Cartier-Bresson’s interest in the luxurious is unending, and compelling. Even a 1975 portrait of Martine Franck, his second wife, captures the subject with a faraway gaze, demonstrating Cartier-Bresson’s simultaneous presence and absence.